Seven takeaways from ECOT’s potential closure

After losing its sponsorship, ECOT, the largest e-school in Ohio, appears to be on the brink of closure.

After losing its sponsorship, ECOT, the largest e-school in Ohio, appears to be on the brink of closure.

After losing its sponsorship, ECOT, the largest e-school in Ohio, appears to be on the brink of closure. Districts and other e-schools are bracing for the possible flood of new students, preparing to hire new teachers, manage students’ transcripts, and get them up to speed mid-year. Not surprisingly, politicians are squeezing the situation for every last drop. Taking hardline stances on charter schools in Ohio is like a free campaign booster shot, with this particular situation offering extra potency. Meanwhile, families of some 12,000 students are dealing with the nightmare of impromptu school shopping.

Much is being said about ECOT right now. This shouldn’t surprise, given its status as the largest and most maligned charter school in Ohio and the role of its founder among the old guard of widely reviled campaign contributors in laying the groundwork for a very partisan charter landscape in Ohio. Each development toward ECOT’s downfall has sharpened new arrows in the quiver from which to take aim against charter schools broadly—a serious portion of which deserve never to be mentioned in the same breath as the near-fallen giant. What, if anything, can be learned and applied from this? Here are some takeaways, beyond the most simplistic and/or politicized ones that have dominated news and social media.

The fallout from ECOT’s likely collapse should force us all to rethink important education policies, including school accountability for graduation rates, how we document student learning (whether by “seat and screen time” or competency), and even admissions and record-keeping policies. Kids and families in Ohio deserve better than what they’ve been through, and are about to go through, if and when ECOT closes its doors.

Over the past few years, there’s been a lot of talk about changing the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System (OTES). That’s because the system has failed to accomplish its intended purposes: It doesn’t differentiate teachers based on performance, nor does it help them improve their practice. It’s also unfair to many educators, it’s a paperwork pileup for administrators, and it’s a time-suck for students who must take local tests solely for the purposes of teacher evaluation. Taken together, Ohio has a policy ripe for major changes.

Enter Senate Bill 240, legislation introduced last December. It adopts the majority of the Educator Standards Board’s recent recommendations, including some promising proposals that if implemented well could change the evaluation system for the better. The most significant change would get rid of Ohio’s various frameworks and weighting percentages. Under the new system, teachers would no longer have a specific, state-mandated percentage of their summative rating determined by student growth measures. Instead, student growth and achievement would be used as evidence of a teacher mastering the various domains of a revised classroom observation rubric. This is definitely a more organic way to measure student growth, but until it’s put in place, we won’t know for sure if it’s a better way.

Not everyone is thrilled with the proposed changes. Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD) CEO Eric Gordon has said that he is reluctant to “move away from the importance of having a student’s performance as part of a teacher’s results.” His disapproval comes despite the fact that the legislation appears to give Cleveland the right to opt out of the new framework and continue implementing existing teacher evaluation law.

As a former teacher who has been evaluated based on student performance, I tend to agree that Gordon is right to want to hold his teachers accountable for student learning. The stakes are too high to do anything less. Unfortunately, OTES doesn’t accurately attribute student performance to all teachers. As previous calculations indicate, 66 percent of Ohio teachers have been judged on student growth using locally developed measures. These measures can include “shared attribution,” which evaluates teachers based on test scores from subjects they don’t even teach, and Student Learning Objectives (SLOs), which are extremely difficult to implement consistently and rigorously, often fail to effectively differentiate teacher performance, and add enormously to the testing burden. It’s possible that Gordon has found a way to fairly hold teachers accountable for student growth in Cleveland, but much of the rest of the state is still struggling with the mechanics of that monumental task.

Potentially fueling Gordon’s interest in this issue is one of the signature aspects of the Cleveland Plan: The district can terminate a teacher who earns an overall evaluation rating of ineffective for two consecutive years. This gives teacher evaluations in Cleveland more teeth than most places, since a similar policy doesn’t exist statewide.

It also brings up an interesting question: If state law changes and removes some of the explicit focus on tying student achievement to teacher evaluations, will a district like Cleveland find it harder to keep its policies in place over time? If that is indeed what happens, Gordon’s district could be forced to keep some low-performing teachers whom it may have otherwise dismissed. It’s hard to blame the superintendent of one of the lowest-performing districts in the state for trying to ensure that his students have the best possible teachers.

The potential solution to this dilemma is three-fold:

First, the state should continue to support the reform efforts known as the Cleveland Plan. The partnership that the General Assembly, Governor Kasich, and Mayor Jackson developed to implement robust reform should be honored. If the state decides to change its broader teacher evaluation package, that’s fine. However, it needs to be crystal clear that CMSD can continue its efforts.

Second, the revised observational rubric that SB 240 calls for must be rigorous and rigorously implemented. It is a waste of time, effort, and money to transition from one system that fails to differentiate teacher performance to another. The department needs to call in a wide array of stakeholders and experts—including leaders like Gordon—to craft a rubric that will accurately differentiate between teacher performances.

Third, the General Assembly needs to recognize that some of the flexibilities Cleveland schools enjoy, like making it easier to dismiss the relatively small number of chronic poor performers, could be useful in other districts. Parents don’t want their kids taught by these teachers, principals don’t want them in their buildings, and other teachers don’t want to work alongside them. If there is a clear, documented history of ineffectiveness, principals should be empowered to do right by students and remove that individual from the classroom. Otherwise, students will pay the price.

Much attention is fittingly paid to race- and income-based achievement gaps in K-12 schools. But research has also documented similar and worrying gender-based gaps in college classes on high-stakes science tests. Analysts have attributed these to variations of “student deficit,” such as unequal K–12 preparation for college-level science, and to “stereotype threat”—the idea that women are led to believe they don’t have the same ability as men to succeed in STEM fields and thus perform poorly at the most stressful moments, like when taking exams. If these gender gaps and their underlying causes remain unaddressed, important and lucrative job paths in fast-growing STEM fields could be closed to many women.

A recent study by Sehoya Cotner and Cissy J. Ballen of the University of Minnesota proffered a different theory for these observed gaps: a “course deficit” model, wherein course structure leads to performance gaps, specifically instances in which high-stakes midterms and finals are the main components of final grades.

Cotner and Ballen looked at nine high-enrollment introductory biology courses at an unnamed large public university with varying mixes of high-stakes and low-stakes assessments comprising their final grades. They analyzed summative course grades and performance on midterm, final, and various lower-stakes assessments as a function of gender and of incoming preparation as measured by composite ACT scores.

Their findings were just as they had predicted: As the percentage of overall grades determined by midterm and final exams increased, the performance gaps on those tests between female and male students increased, too; and, as that percentage decreased, the gaps disappeared and sometimes even reversed. They surmise that, “[F]or some individuals, performance on exams may not reflect a student's actual content knowledge.”

Cotner and Ballen also conducted three case studies to dig down into specific course-based variables. All three reinforced the general findings, leading them to conclude that to better support women pursuing degrees in STEM field, universities should offer more courses that deemphasize high-stakes exams and rely more on active learning techniques, such as group projects, low-stakes quizzes and assignments, class participation, and in-class activities such as labs.

Even before conducting this study, Cotner and Ballen were long-time proponents and researchers of active learning techniques and mixed assessments. And although their conclusions here are compatible with the data tested and with their previous research, they leave too many questions unanswered. Wouldn’t using ACT science scores instead of less specific composite scores better determine incoming students’ preparation? After noting that performance patterns appear to support stereotype threat, why not test for it? Why not also control for the instructor’s gender? They also boldly proclaim that “the lower-value exams assessed the same content knowledge as the high-value exams, a finding that should assuage concerns that low-stakes testing means a watering-down of expectations.” But if a test constitutes a smaller percentage of a student’s grade than a midterm or final, wouldn’t the less-weighted exam be shorter and less extensive? Cotner and Ballen should have at least investigated test rigor as a factor rather than assuming it was the same in all cases.

“Why so few women in science?” asked a 2010 report from the American Association of University Women (AAUW). Stereotype threat was at the top of its list, followed by gender bias. And today’s research continues to argue strongly that stereotype threat is still at play today in STEM fields. Any study looking for an alternate theory must therefore clear a higher bar. This study needs expanding and deepening to approach that bar.

Source: Sehoya Cotner and Cissy J. Ballen, “Can mixed assessment methods make biology classes more equitable?” PLOS ONE (December, 2017).

In 2009, Public Impact launched the Opportunity Culture initiative, which identifies ways for effective teachers to take on roles that enable them to positively affect many more students.

For example, under the multiclassroom leadership model, a highly effective teacher is placed in charge of a team of teachers and is accountable for the learning of all the students who are taught by her team. This multiclassroom leader is responsible for supervising instruction, evaluating and developing teachers’ skills, and facilitating team collaboration and planning. The team leaders are either not assigned students or given a light teaching load that enables them to focus on their mentorship role. The other model used in the study’s data—the time-swap model—uses learning stations facilitated by paraprofessionals to enable effective teachers to lead instruction for more students.

Earlier this month, CALDER released a working paper that examined the relationship between Public Impact partner districts that adopted these staffing models and student achievement in math and reading. Data was drawn from three public school districts: Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina, which contributed nearly 90 percent of the students in the research sample, Cabarrus County Schools in North Carolina, and the Syracuse City School District in New York. All three districts implemented the new staffing models in a minimum of three schools for at least two academic years. In total, the sample comprised more than 15,000 students.

Most students experienced the multiclassroom leadership model, either through direct instruction by a multiclassroom leader or via a teacher on a team overseen by a leader. Student achievement was reported using the respective state’s standardized tests. Although random assignment was not possible—schools were targeted for participation by their districts and then chose whether to participate—the research approach is similar to other studies that have measured the impact of certain teachers, such as Teach For America corps members, on student achievement.

The study finds that participating schools significantly improved students’ math performance. The multiclassroom leadership model, in particular, produced larger math gains than other models. Though many models were also correlated with positive and significant effects for reading, some were not. And overall results for models other than the multiclassroom leadership model were mixed.

This study suggests that the Opportunity Culture initiative is a promising, innovative strategy. It increases math achievement and offers teachers upward career mobility without requiring them to leave the classroom for administrative positions—a problem that regularly plagues districts and schools looking to retain their best teachers. In addition, although teachers are paid substantial salary supplements, the initiative uses models that operate within the constraints of a school’s normal operating budget—an intriguing premise that better compensates teachers without affecting the bottom line. Districts looking for an innovative way to empower and improve their teaching force would do well to take a look at this program.

SOURCE: Ben Backes and Michael Hansen, “Reaching Further and Learning More? Evaluating Public Impact’s Opportunity Culture Initiative,” American Institutes for Research (January 2018).

Earlier this week, Chiefs for Change (CFC) announced that Ohio’s Superintendent of Public Instruction, Paolo DeMaria, joined their network. CFC is a nonprofit, bipartisan network comprising state and district education chiefs who advocate for innovative education policies and practices, support each other through a community of practice, and nurture the next generation of leaders. The network is made up of members who lead education systems serving 7.2 million students, 435,000 teachers, and 14,000 schools.

According to the CFC website, members of the network “share a vision that all American children can lead fulfilling, self-determined lives as adults.” Though it is made up of diverse members with various viewpoints, the chiefs find common ground in five key areas: 1) access to excellent schools, 2) quality curriculum, 3) fully prepared and supported educators, 4) accountability, and 5) safe and welcoming schools.

Here’s a look at a few specific policies supported by CFC and what they look like in Ohio:

School choice

In a statement on school choice released last year, CFC members asserted that “school choice initiatives have the potential to dramatically expand opportunity for disadvantaged American children and their families.” We’ve seen this firsthand in Ohio, where school choice options like high-performing charter schools and open enrollment policies have led to improved student outcomes and a broader range of opportunities. To be sure, Ohio’s record isn’t spotless. There’s still plenty of work to be done. But the Buckeye State is on the right track, and we’re confident that Superintendent DeMaria will continue to focus on quality choices for all families in Ohio.

School funding

School funding has long been a hot topic in Ohio. As part of their support for quality educational opportunities for all students, CFC advocates for “fair funding for schools proportionate to the learning needs of students.” In layman’s terms, this means that taxpayer funding should go to the students who need it most. As former state budget director and associate superintendent of ODE’s school finance office, few in Ohio have a deeper knowledge of the state’s funding system than Superintendent DeMaria. Lending his voice to ensure that all students, no matter their choice of schools, have the resources necessary to succeed would be powerful as legislators wrestle with funding policies.

Teacher policy

CFC believes that teachers should be well-prepared, rewarded for their skills and impact on student learning, provided with opportunities to expand their leadership, and supported with timely and meaningful evaluation and feedback. To his credit, Superintendent DeMaria has already been active in this area: In the fall of 2016, he asked the Educator Standards Board to review the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System. This resulted in recommendations that have now been incorporated into Senate Bill 240, legislation introduced last December that could improve the evaluation system. DeMaria was also vocal about refining the Resident Educator Summative Assessment for educators new to the profession; that initiative yielded significant revisions.

Accountability

Last year, Ohio lawmakers began mulling possible changes to the state’s school report cards. Fordham offered a few recommendations to consider, including simplifying the report card and creating a better balance between achievement and growth metrics. At CFC, members have voiced their support for holding schools accountable for student learning according to “standards benchmarked against those of high-performing states and countries.” Their stance has also included support for “radical change” in struggling schools, which they argue is not only possible but reliably doable. Ohio has an accountability system that, though it could use some simplification and tweaks, is strong compared to other states. Our ESSA plan—recently approved by Secretary DeVos—already contains many of the policies and practices that CFC advocates for. As the debate continues over how to improve Ohio’s school report cards, having a state chief willing to maintain high academic expectations will be essential.

***

Of course, DeMaria doesn’t have to heed any of CFC’s recommended policies and practices. But by joining CFC, he has made clear his commitment to opening quality educational opportunities to all and finding ways to lift student outcomes. We commend him for taking this bold step forward.

As reported by the Dispatch last week, Columbus City Schools has unveiled plans to expand selective admission among its magnet schools next year. This is a positive step in an often criticized district—an effort that should be applauded and helped to grow.

Twenty-five years of school choice in Ohio have largely laid to rest the archaic notion that a home address will determine what schools children will attend from Kindergarten through high school. Interdistrict open enrollment, charter schools, private school scholarships, home schooling, virtual schooling, and independent STEM schools render district boundaries all but irrelevant to parents who are able to navigate these options. Even within districts, specialized schools, programs that look like schools, and lottery-based magnet schools have proliferated, further eroding address-based school assignments and rigid feeder patterns. This is all for the good.

A lesser-known addendum to that list is selective admission, whereby certain schools are allowed to prioritize a percentage of their seats for students who meet particular criteria. Ohio has allowed selective admission—with some important caveats—since 1990, and Columbus City Schools was the first district in the state to make use of this option. Today, five of the district’s magnet schools include a selective admission component: Two are general education and three are arts-focused. All five prioritize 20 percent of their seats for students with strong academic and disciplinary records; the arts schools also require auditions in one or more art forms. If there are more applicants than spots, a lottery is held. The Dispatch story highlighted the waiting lists at all five schools as applicants outnumber available seats—a sure sign of parental interest.

The newly proposed sixth school to adopt this pattern is Columbus Africentric School, a longstanding specialized K-12 school with an immersive focus on African and African-American history and culture. Africentric has recently relocated to a crown jewel of a new facility, and the district is proudly promoting it. Its history of athletic success has traditionally been a big draw, and the school board seems to feel that having a selective concentration of students with excellent academics and good behavior would be another selling point. Thus the district petitioned the State Board of Education to approve it starting next year.

Of course the request should be approved. But why should Columbus (or any district) even have to ask for permission from the state to make this kind of change? Efforts such as this should be a matter of local control, not a state-level decision.

In 1990, concerns about exclusion are what drove Ohio to put this sort of restriction on where and how selective admission could be implemented. The landscape is very different today, however, as more parents demand more and better schooling options for their daughters and sons. In light of this reality, increasing intra-district choice is smart policy. It allows districts to innovate, to create the schools that parents want, and to compete with other schools of choice. It is another break in the "zip code is destiny" approach of yesteryear, an approach that limits kids’ options rather than expanding them. The sooner that approach goes away, the better for Ohio’s children.

Districts shouldn’t have to beg the state for flexibility around admissions policies. Columbus’s initial plan to practice selective admission for 35 percent of the seats in Africentric was reduced by the state to conform to an arbitrary 20-percent limit before the final request was submitted. Who knows better what district parents want and what district schools can accommodate? If that many parents of students with high academics and low discipline want in to Africentric, they should be allowed to do so. Who knows what greater success the five original schools could have achieved had they not been so limited? The existing waiting lists in those schools likely point to the answer.

To be clear, none of these schools are stellar academic performers, and the selectivity being applied is not particularly rigorous. These are not—and should not be confused with—“exam schools” in any way. What they are are better-than-average urban district schools that have drawn plenty of interest from parents and students, most likely because of their alternative focus, boundary-busting admissions, and selective admissions policies (however small that population is). That alone is good news for Columbus and an indication that a new focus on quality could emerge from the status quo. Parents are interested, the school board is all in, and the potential benefits are there. So the state should get out of the way and let the good work proceed.

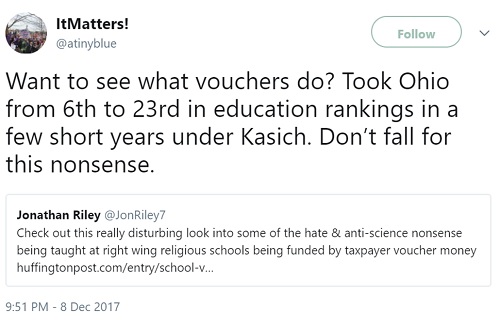

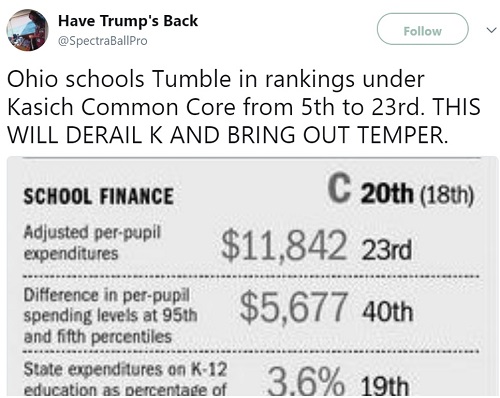

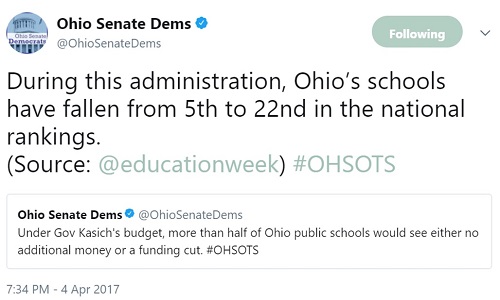

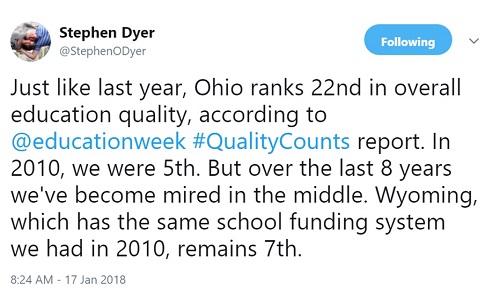

Education Week just released its 22nd annual report and rankings of state education systems. Faster than we can read the report or its accompanying coverage—which this year includes a worthwhile look at “five common traits of top school systems” and “five hurdles” standing in the way of improvement—alarmed observations about Ohio’s rankings “drop” have begun to emerge. They point out that Ohio was ranked 5th in 2010, 23rd in 2016, and 22nd in both 2017 and 2018, largely to score political points suggesting that the current administration has been asleep at the wheel.

We’ve been down this path before, but let’s revisit two significant problems with this interpretation. Last year when the ratings were released, I dove into an analysis exploring some of the likely causes for Ohio’s near twenty-slot fall in the relative rankings since 2010.

The rating system changed

Education Week undertook a significant overhaul of its rating system between 2014 and 2015, prohibiting meaningful comparisons of overall rankings over time. They eliminated three categories and now only include the following components: Chance for Success, an index with thirteen indicators examining the role that education plays from early childhood into college and the workforce; School Finance, a grade based on spending and equity, which takes into account per-pupil expenditures, taxable resources spent on education, and measures of intra-district spending equity; and K-12 Achievement, a grade based on eighteen measures of reading and math performance, AP results, and high school graduation.

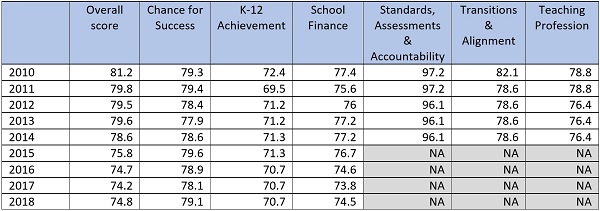

The three categories axed after 2014 included Ohio’s highest-rated areas, Standards, Assessments and Accountability, and two other areas (Transitions and Alignment and Teaching Profession) where Ohio posted solid scores. The table below illustrates how Ohio scored in each category over time and helps explain why Ohio’s absolute score fell given changes to the scoring system.

Table 1: Ohio scores on Education Week’s Quality Counts report card over time

Relativity

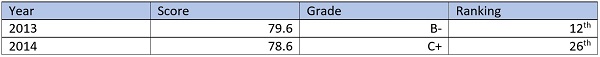

Education Week’s rankings are relative, and Ohio’s shift over time has just as much to do with what other states are or aren’t doing. Last year, I hypothesized that Ohio’s fourteen-slot fall between 2013 and 2014 very likely resulted from the changes rapidly occurring in other states that earned them extra points Ohio had already had under its belt. In fact, the year that its relative ranking plummeted, Ohio’s actual score only changed by a single digit.

Table 2: Ohio’s dramatic rankings shift

Ohio’s actual score changes across nearly a decade among the components that have remained consistent have been fairly modest. For instance, in 2010, the state’s score on K-12 Achievement was 72.4, and in 2018, it was 70.7.

Table 3: Changes to Ohio’s Education Week scores, 2010-2018

Despite these minor changes in scores, some would have you believe that Ohio’s education system has suffered cataclysmically. As I warned last year, Ohio’s ranking has become easy fodder for those with an ax to grind with the state’s education policies. Unfortunately, that fact remains true a year later. This is not to say that the state’s education policies have been above reproach or that we’re where we need to be. Rather, seeing data used so out of context and without understanding the causes behind such changes leaves us ill-equipped to make meaningful improvements. Consider these tweets that basically assign blame for changes in the state’s ranking to just about anything the tweeter wants to target:

Given how heavily the Quality Counts ranking is cited throughout the year, understanding the finer details of the rankings would likely generate a more productive discussion on how to improve education in Ohio. That is the goal, right?