Do good schools leave low-achieving students behind?

How to ensure that all students are making learning gains

How to ensure that all students are making learning gains

In the reauthorization debate, civil rights groups are pressing to have ESEA force states to "do something" in schools where students as a whole are making good progress but at-risk subgroups are falling behind. Their concerns are not unreasonable, to be sure. Schools should ensure that all students, especially those who are struggling academically, are making learning gains.

Yet it’s not clear how often otherwise good schools fail to contribute gains for their low-achievers. Is it widespread problem or fairly isolated? Just how many schools display strong overall results, but weak performance with at-risk subgroups?

To shine light on this question, we turn to Ohio. The Buckeye State’s accountability system has a unique feature: Not only does it report student growth results—i.e., “value added”—for a school as a whole, but also for certain subgroups. Herein we focus on schools’ results for their low-achieving subgroups—pupils whose achievement is in the bottom 20 percent statewide—since this group likely consists of a number of children from disadvantaged backgrounds, including from minority groups.

(The other subgroups with growth results are gifted and special needs students, who may not be as likely to come from disadvantaged families or communities. The state does not disaggregate value-added results by race or ethnicity.)

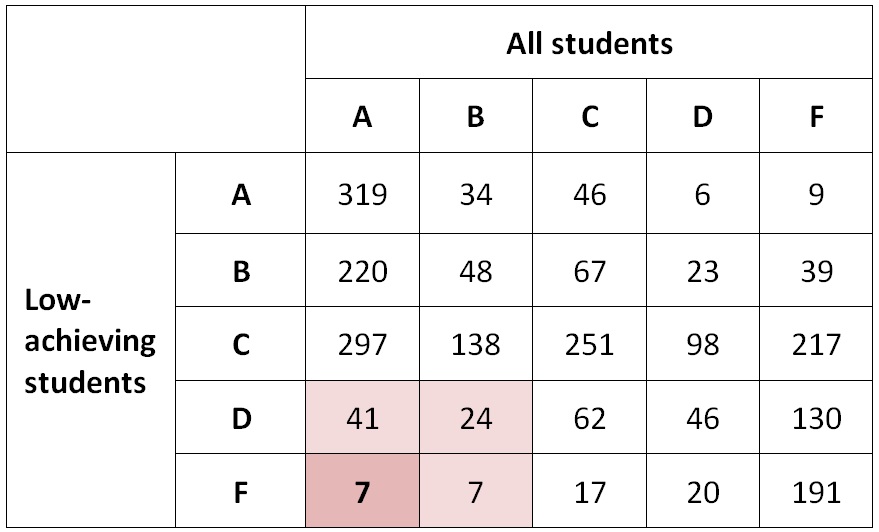

In 2013–14, Ohio awarded A–F letter grades for 2,357 schools along both the overall and low-achieving value-added measures. These schools are primarily elementary and middle schools (high schools with grades 9–12 don’t receive value-added results). The table below shows the number of schools within each A–F rating combination.

Table 1: Number of Ohio schools receiving each A–F rating combination, by value added for all students and value added for low-achieving students, 2013–14

You’ll notice that a fairly small number of schools perform well overall while flunking with their low-achievers. Seventy-nine schools—or 3.3 percent of the total—received an A or B rating for overall value added while also receiving a D or F rating for their low-achieving students. (Such schools are identified by the shaded cells.) Meanwhile, just seven schools—or a miniscule 0.3 percent—earned an A on overall value added but an F on low-achieving value added. These are the clearest cases of otherwise good schools in which low-achievers fail to make adequate progress.

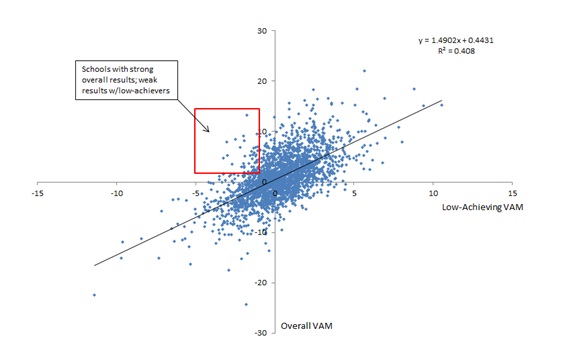

In the chart below, we present each school’s value-added scores, both overall and for their low-achieving subgroup. What becomes apparent in this chart is the fairly close relationship between a school’s overall performance and its performance with low-achievers. In other words, if a school does well along overall value added, it typically does well with low-achievers. Conversely, if a school does poorly overall, it’s also likely to perform poorly with low-achieving students. Worth noting, of course, is that the enrollment of some schools consists of a sizeable number of low-achievers; in these cases, we’d expect a very close correlation.

Chart 1: Value-added scores of Ohio schools, by value added for all students (vertical axis) and value added for low-achieving students (horizontal axis), 2013–14

Data source (for Table 1 and Chart 1): Ohio Department of Education Notes: The overall value-added scores are based on a three-year average (vertical axis), while scores for low-achieving students are based on a two-year average (horizontal axis). Ohio first implemented subgroup value-added results in 2012–13, hence the two-year average. The state has reported overall school value added since 2005–06. The number of schools is 2,357. Results are displayed as “index scores,” which are the average estimated gain/standard error; these scores are used to determine schools’ A–F rating. The correlation coefficient is 0.64.

So do good schools leave low-achievers behind? Generally speaking, the answer is no. A good school is usually good for all its students (and a bad school is typically bad for all its students).

Are there exceptions? Certainly—and thought should be given around what should be done in those cases. Local educators, school board members, parents, and community leaders must be made aware of the problem, and they should work together to find a remedy.

But should state or federal authorities step in to intervene directly? That’s less clear. While the state might do some good for low-achievers by demanding changes, it’s also equally plausible that intervention could aggravate the situation, perhaps even damaging an otherwise effective school.

The Ohio data show it to be a rare occurrence when a school performs well as a whole but does poorly with its low-achieving subgroup. One might consider this a matter of common sense—it’s plausible that high-performing schools contribute to all students’ learning more or less equally. Do these exceptions justify a federal mandate that may or may not work? In my opinion, probably not. Do these isolated cases justify derailing an otherwise promising effort to reauthorize ESEA? Definitely not.

Passed by the Ohio House and Senate, House Bill 70 sharpens the powers and duties of “academic distress commissions” (ADCs) in Ohio and now awaits the signature of Governor Kasich.

Academic distress commissions were added to state law in 2007 as a way for the state to intervene in districts that consistently fail to meet standards. Two districts (Youngstown and Lorain) currently operate under the auspices of an ADC, but the new bill only applies to the former (as the latter’s commission is too new) and to any future districts which fall into academic distress after the bill’s effective date. Despite being nicknamed the “Youngstown Plan,” HB 70 doesn’t specifically mention Youngstown; on the contrary, it applies statewide and significantly alters the way any ADC—whether already existing or established in the future—is run. Moving forward, a new ADC will be established if a district receives an overall F grade on its state report card for three consecutive years. As for districts already under an ADC (Youngstown and Lorain), the structure of their ADCs will change on the bill’s effective date of compliance.

Let’s examine four of HB 70’s biggest changes to ADCs.

1. Lessening the power of the local school board

In current law, ADCs consist of five voting members: three appointed by the superintendent of public instruction and two by the president of the district’s board of education. HB 70, however, lowers the school board’s number of appointees from two to one. This allows one member of the ADC to be appointed by the mayor of the municipality in which the district is located. It therefore limits the board’s ability to approve or reject the overall plan for the ADC, which is crafted by the CEO and approved by the members of the ADC. House Bill 70 clearly puts the ADC in the driver’s seat.

Most interestingly, if the district has failed to earn a C by its fourth year under the ADC, the elected school board will cease to exist. Instead, a new board of education will be appointed by the mayor from a slate of candidates nominated by a panel consisting of two people appointed by the mayor, one principal employed by the district and selected via vote by the district’s principals, one teacher appointed by the local union, one parent appointed by the parent-teacher association, and the chairperson of the academic distress committee. This procedure is somewhat akin to the mayoral control of Cleveland, New York City, and Washington, D.C. In fact, HB 70 also includes provisions that outline how a referendum election would eventually determine whether the mayor continues to appoint the board or the board returns to being a locally elected body. Even with a new board—appointed or not—the CEO retains “complete operational, managerial, and instructional control of the district.”

2. Empowering a CEO

HB 70 calls for the appointment of a powerful chief executive officer by the members of the academic distress commission. The bill states that the CEO has “complete operational, managerial, and instructional control of the district.” That includes replacing school administrators, hiring new employees, establishing employee compensation, allocating teacher class loads, conducting employee evaluations, setting the school calendar, creating the district’s budget, contracting for services, determining curriculum, and setting class sizes. As a result, the possibilities for reform are numerous: Consistently failing districts under an ADC could extend the school day or year; institute alternative pay schedules, including merit pay or offering higher pay for harder-to-fill positions like high school sciences; alter teacher class loads to allow for hybrid teachers; or contract for wraparound services in a more innovative way. A superintendent of any traditional district, failing or otherwise, can technically already recommend reforms like this. So why is the role of the CEO so radical?

For starters, it’s because of collective bargaining changes. Bill text states that the CEO “shall represent the district board during any negotiations to modify, renew, or extend a collective bargaining agreement entered into by the board.” Traditionally, a superintendent is bound by a collective bargaining agreement negotiated by the school board and the local union. But in the case of HB 70, the CEO has the right to refuse to modify or extend the agreement. Similarly, if it comes time to renew the agreement, the CEO has full control over the negotiations and is “not required to bargain on subjects reserved to the management and direction of the school district.” In other words, the key functions of district management are not up for negotiation.

The CEO’s role is also revolutionary because of the steadily increasing power afforded to her if a district does not achieve an overall grade of C or higher on its state report card. If, after one year under the ADC, the district doesn’t earn a C, the CEO is empowered to “reconstitute any school operated by the district.” This means the executive can do any of the following: Change the mission or curriculum of the school, replace the school’s principal or administrative staff, replace a majority of the staff (including teaching or nonteaching employees), contract with a nonprofit or for-profit to manage school operations, reopen the school as a charter, or permanently close the school. The last two options are the most intriguing. Reopening a school as a charter is an intervention model that is supported by the U.S. Department of Education (specifically, it’s called the “restart model”) and has been used in other states.[1] Closing schools, although politically divisive, has been proven to increase the academic achievement of affected students—especially if they are placed in a higher-performing school. These two powers offer the CEO an unprecedented ability to change the landscape of a failing district.

If the district fails to achieve a C grade for additional years, the CEO is given greater tools. At the two-year mark, the CEO is permitted to “limit, suspend, or alter any provision of a collective bargaining agreement entered into, modified, renewed or extended on or after the effective date” of the bill (the CEO cannot, however, reduce base hourly pay or insurance benefits). All of these powers continue to belong to the CEO if the district fails to earn a C for a third year in a row.

3. Expanding quality school choice

HB 70 expands choice in two ways. First, it allows for the creation of a high-quality school accelerator for the district. This accelerator is not operated by the district, and the CEO has no authority over it. Its purpose is to promote high-quality schools, recruit high-quality sponsors for charters, attract new high-quality schools to the district, and lead improvement efforts by increasing “the capacity of schools to deliver a high-quality education.” (Cincinnati is in the beginning stages of developing an accelerator based on Indianapolis’s successful Mind Trust organization.) By operating independently of the district and the CEO, the accelerator is intended to be insulated from political and financial pressures and therefore objective in its pursuit of high-quality options and agnostic to a school’s sector. HB 70 also designates every student in an ADC district “eligible to participate in the Educational Choice Scholarship program,” which is Ohio’s voucher program for students in failing schools. This ensures that even if the schools in the ADC continue to struggle to meet benchmarks, families will have the choice to send their children to a private school through the state’s voucher program.

4. Requiring high standards for dissolving the ADC

In order to transition out of an ADC and back to a traditional system, a district must meet a few high expectations. First, it must earn an overall grade of C on its state report card. Once this grade is obtained, the district must have an overall grade higher than F for two more years in a row (the first C grade doesn’t count as one of these two years). If the district is given an F before achieving two consecutive years of higher grades, it returns to its original status in the ADC and must start the process over again by earning another C. However, if the district manages to earn grades higher than F for two consecutive years, the CEO will “relinquish all operational, managerial, and instructional control of the district to the district board and district superintendent and the academic distress commission shall cease to exist.”

***

Overall, HB 70 makes significant changes to Ohio’s academic distress commissions. By lessening the power of the local school board, transferring that power to an appointed CEO, opening the door to mayoral control, and expanding school choice, academic distress commissions have transformed into a far more aggressive reform. Only time will tell if this new structure will bear the kind of fruit that kids in places like Youngstown so desperately need.

[1] The best-known uses of the restart model include Louisiana (the Recovery School District, or RSD) and Tennessee (the Achievement School District, or ASD.) To be clear, there are differences between the ADC legislation in Ohio and these recovery districts. For example, the RSD and ASD are statewide districts. Though the RSD is often linked to New Orleans and the ASD to Memphis, both districts operate schools outside those cities (the ASD has schools in and around Nashville, and the RSD has schools in Baton Rouge). The ADCs in Ohio, on the other hand, are much more locally driven: They exist only in certain districts and—up until a certain point outlined in the law—still have locally elected school boards (though the school board’s power is significantly limited). For more on recovery school districts, check out Fordham’s latest report, Redefining the School District in America.

Over the last twenty years, Ohio has transformed its vocational schools of yesteryear—saddled with limited programs, narrowly focused tracks, and low expectations—into a constellation of nearly three hundred career and technical education (CTE) locations that embed rigorous academics within a curriculum defined by real-world experience. (For more on Ohio’s CTE programs, see here.) According to a new report from Achieve, these transformations have put the Buckeye State on the cutting edge in CTE.

What sets Ohio apart from other states offering CTE is its commitment to high expectations. This principle was perfectly encapsulated in 2006, when the legislature was debating whether career-technical planning districts (which handle the administrative duties of CTE programs) should be held to the same standards as traditional schools. Many CTE leaders were determined that their students should be held to the same rigorous expectations as other students. Fast forward to the 2014 mid-biennial review legislation, and their determination finally became reality: Ohio now has three pathways to graduation, one of which is designed for CTE students. This pathway requires that any CTE graduate must earn “a state-approved, industry-recognized credential or a state license for practice in a vocation and achieve a score that demonstrates workforce readiness and employability on a job skills assessment.” In addition to high school graduation requirements, most CTE students also earn college credit while still in high school through dual enrollment, AP classes, and “articulate credits” (completing a specific course and earning a certification). This has led to thousands of dollars in college cost savings and opened the door to millions of dollars in scholarships.

In order to ensure accountability, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) started assigning report cards to career-technical planning districts back in 2012. They report student achievement (based on CTE-aligned assessments), graduation rates, student preparation (based on dual enrollment, AP, and honors diploma numbers), and post-program outcomes. (You can check out the report cards here).

Achieve also incorporated student spotlights and close-up looks at three CTE locations: Auburn Career Center, Centerville High School, and Excel TECC. These close-ups include looks at the diverse programs and pathways available to students, student outcomes, and quotes from business leaders who are quick to point out that CTE programs are just as beneficial for local businesses as they are for students and schools. The authors also explain how Ohio successfully empowers its CTE teachers to partner with businesses and implement innovative ideas.

Overall, the state’s CTE future looks bright—especially given Governor Kasich’s strong support. Keep doing what you’re doing, Ohio.

SOURCE: “Seizing the Future: How Ohio’s Career and Technical Education Programs Fuse Academic Rigor and Real-World Experiences to Prepare Students for College and Work,” Achieve (June 2015).

Many would argue that the media doesn’t give education the ink or airtime it deserves. But surprisingly, a new publication suggests that—at least at the local, state, and regional levels—K–12 issues receive a fair amount of attention.

In this study, policy strategist Andrew Campanella used the NewsBank database to search for key education terms in headlines and ledes. In total, he compiled stories from more than five thousand news sources and filtered out results about higher education. He found that education coverage was up 7.7 percent in 2014 relative to the twenty-five year trend, and also discovered that local, state, and regional outlets featured K–12 education in about 6.8 percent of stories. That’s a decent proportion of stories when considering the various topics covered by media outlets. In contrast, national media was about three times less likely than local media to feature education.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it isn’t education policy driving the news coverage in local outlets. Sports were by far the most covered “education” topic, appearing in 13.6 percent of state, local, and regional education stories. Special events like pep rallies and field trips were a distant second at 5.1 percent. When policy was covered, the study found that school funding (5 percent) and school choice (2.3 percent) were most prevalent. School choice coverage has fluctuated greatly in the past twenty-five years, declining from its peak in 2000 but reaching another upward trend in 2011. In addition, stories about school quality were down more than 46 percent in 2014, accounting for a mere 0.08 percent of education stories.

Meanwhile, two policy areas—state standards and safety—were identified as receiving more coverage in recent years. The former is undoubtedly a result of the debate around the Common Core State Standards, and the latter is likely an effect of tragic acts of violence.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway is that the perception of our education system is largely reflected through local reporting, which is typically geared toward the positive—like a football team’s big win or an innovative field trip. This might explain why Americans generally view their own schools in a more positive light than the education system as a whole. (Of course, there are exceptions; a story of malfeasance in a school is apt to make the local news too.) It’s essential for education reformers to use strategies that effectively engage the local media. If they don’t, calls for change will rarely break through.

This study suggests that education coverage increased in 2014, but with the huge expenditures of tax dollars on education each year, more is needed to adequately inform parents and decision makers about the state of our school system and the choices available within it.

SOURCE: Andrew Campanella, “Leading the News: 25 Years in Education Coverage,” Campanella Media and Public Affairs, Inc. (June 2015)

The Ohio Education Research Center (OERC) recently reported the teacher evaluation results from 2013–14, the first year of widespread implementation of the state’s new evaluation policy. The report should serve as an early warning sign while also raising a host of thorny questions about how those evaluations are being conducted in the field.

The study’s main finding is that the overwhelming majority of Ohio teachers received high ratings. In fact, a remarkable 90 percent of teachers were rated “skilled” or “accomplished”—the two highest ratings. By contrast, a mere 1 percent of Buckeye teachers were rated “ineffective”—the lowest of the four possible ratings. These results are implausible; teaching is like other occupations, and worker productivity should vary widely. Yet Ohio’s teacher evaluation system shows little variation between teachers. It’s also evident that the evaluation is quite lenient on teacher performance. But there’s more. Let’s take a look at a few other data points reported by OERC that merit discussion.

1. Most teachers are not part of the value-added system

Given the controversy around value added in teacher evaluation, it may surprise you that most Buckeye teachers don’t receive an evaluation based on value-added results. (Value added refers to a statistical method that isolates the contribution of a teacher to her students’ learning as measured by gains on standardized exams.) Under state law, teachers with instructional responsibilities in grades and subjects in which value added is calculated (presently, grades 4–8 in math and reading) must be evaluated along those results. But as Chart 1 shows, most Ohio educators teach in grades and subjects where no value-added measure exists; thus, they are evaluated along other growth measures such as vendor assessments or student learning objectives (SLOs). These growth measures made up 50 percent of teachers’ overall ratings in 2013–14.[1]

Chart 1: Distribution of Ohio teachers by the type of student growth measure used in the evaluation, 2013–14

[[{"fid":"114524","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"type":"media","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default"},"link_text":null}]]

Source: Marsha Lewis, Anirudh Ruhil, and Margaret Hutzel, Ohio’s Student Growth Measures (SGMs): A Study of Policy and Practice (Columbus, OH: Ohio Education Research Center, 2015), page 2

With relatively few teachers are in the value-added system, it’s important that we take a closer look at the other growth measures. What do we know about the vendor assessments? For instance, how are schools and teachers selecting them? Are they comparable to using state exams to measure gains? How are the gains calculated, and how are non-classroom effects on gains “controlled” for? What about the SLOs, local assessments developed by teachers? What are their features? How much do they vary from teacher to teacher, or from school to school? How are schools ensuring that the SLOs are robust, especially since there seems to be an inherent conflict of interest when teachers create their own assessment and growth tools?

Meanwhile, the practice of shared attribution—ascribing a school or district’s overall or subgroup value-added result to an individual teacher—deserves serious inquiry too. Interestingly, the OERC report found that 31 percent of evaluated teachers used shared attribution to some extent. (District boards, in consultation with teachers, approve the degree to which shared attribution is used for certain teachers.) How do districts decide the weight placed on shared attribution? Is the district, building, or subgroup value-added result typically used? Why are certain districts permitting its use? Do these districts value teamwork more than others? Or do they have less reason to be concerned about “free riding”—when certain employees shirk, even while receiving credit for the greater organization’s performance?

Maybe there are easy answers to these questions about these non-value-added measures, which apply to 80 percent of Ohio teachers. But this analyst hasn’t seen them. Shouldn’t there be troves of research on how these growth measures are used? Where are the studies demonstrating that these are fair and objective measures of teacher productivity?

2. The evaluation is tougher for teachers in the value-added system

If you’re an educator in the value-added system, you’re less likely than your colleagues to earn a top rating. Consider the results presented in Chart 2: Just 31 percent of teachers fully in the value-added rating system received an overall rating of accomplished, while 50 percent of teachers in the SLO/shared attribution category were rated accomplished. That’s a fairly stark difference, and it indicates that objectively measured performance, as happens in the value-added system, is a tougher standard than the other measures. When the accomplished and skilled ratings are combined, less difference emerges across teachers, as categorized by their growth measure. Yet teachers in the value-added system still appear slightly disadvantaged relative to their colleagues.

Chart 2: Percentage of Ohio teachers receiving the two top overall ratings (accomplished and skilled, the former being the highest rating) by the type of student growth measure used, 2013–14

[[{"fid":"114525","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"type":"media","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default"},"link_text":null}]]

Source: Lewis, Ruhil, and Hutzel, Ohio’s Student Growth Measures, page 33

The student growth component, not the observational portion of the evaluation, drives the differences between teachers in the value-added system and those who are not. As Chart 3 demonstrates, just 32 percent of teachers fully in the value-added system received the highest possible rating on their evaluation’s growth component (“above”), while 54 percent of teachers in the SLO or shared attribution category received this rating. The evaluation results align with one administrator’s comment to the OERC researchers: “Value-added versus SLOs is not an equal measure.”

Chart 3: Percentage of Ohio teachers receiving each possible rating on the student growth portion of their evaluation by the type of growth-measure used, 2013–14

[[{"fid":"114526","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"type":"media","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default"},"link_text":null}]]

Source: Lewis, Ruhil, and Hutzel, Ohio’s Student Growth Measures, page 33

3. Classroom observation ratings are lenient

As noted above, student growth measures, including value added if available, comprised 50 percent of teachers’ evaluations in 2013–14. So what about the other half of the evaluation—classroom observations? In Chart 4, we see that 70 percent of teachers were rated skilled and another 24 percent accomplished by their classroom observer. Meanwhile, just a miniscule number of teachers were rated ineffective—less than 1 percent.

Chart 4: Percentage of Ohio teachers (across all student growth categories) in each classroom observation rating category, 2013–14

[[{"fid":"114527","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"type":"media","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default"},"link_text":null}]]

Source: Lewis, Ruhil, and Hutzel, Ohio’s Student Growth Measures, page 2

The results from the classroom observation side of the evaluation could be considered somewhat predictable. The New Teacher Project documented in The Widget Effect that practically every teacher receives a satisfactory rating when evaluations are observation-based. This reflects a bit of common sense, too: It’s probably difficult for a principal or coworker, who works with a teacher daily, to be a tough or impartial evaluator. (It’s been rightly suggested that external observers may be more appropriate for observation purposes.) The positive results could also reflect something of an acquiescence bias—the tendency toward “yeasaying.” For instance, classroom observers may be inclined to report that a teacher did this or that pretty well, instead of giving an honest performance appraisal. This problem may be aggravated by the fact that principals have almost no authority over hiring, promotion and pay raises, or dismissal. Hence, there’s little incentive for them to conduct tough-minded evaluations, because they can’t connect the evaluation results to staffing decisions. Finally, the results could also reflect the fact that teachers are notified in advance when their formal classroom observations will occur, leading to a positively skewed evaluation relative to their everyday practices.

Conclusion

The first-year results indicate that Ohio’s evaluation system isn’t working properly. (To be sure, this isn’t a problem unique to Ohio; other states appear to be experiencing similar issues.) The evaluation system doesn’t seem to evaluate teachers in an equally rigorous manner across the different grades and subjects; it appears to be excessively lenient, especially when it comes to the observation portion; and it’s not clear how robust the non-value-added measures of growth are. Investigating and correcting these issues, if necessary, will require the full commitment of Ohio policymakers and practitioners. A halfhearted effort is likely doomed to fail.

[1] In 2013–14, Ohio’s evaluation system was based half on classroom observation, which applied to all teachers, and half on student growth measures, which varied depending on the grade and subjects taught. The state established an alternative evaluation framework available to schools in 2014–15—and that alternative framework will change again with the enactment of House Bill 64 in June 2015.

The dire findings on the performance of Ohio’s charter schools published by Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) have provided the badly needed political impetus to reform the state’s charter school laws. Now, however, it appears that not only are these reforms at risk, but lawmakers are actually considering steps to weaken one of the few aspects of the existing accountability system that works.

If existing measures show that charter schools are underperforming, it seems that some charter operators have decided that it would be easier to change the yardstick used to assess them than to improve student achievement.

As the Columbus Dispatch reported recently, at least one charter school operator is pushing Ohio lawmakers to replace the state’s current “value-added” accountability framework with a “Similar Students Measure” (SSM), similar to metrics used in California. Doing so would be a gigantic step back in accountability and would make charter school student achievement look better than it really is.

Here is some background: The state of California developed such a measure back in the 1990s, before the statistical models used to estimate value added were widely available. The state and various other groups have continued to use this method because, unlike Ohio, California still has no way to link test scores to students over multiple years, which is necessary to estimate value-added models.

Think of SSM as a poor man’s value added—indeed, the California Charter Schools Association calls it a “proxy value-add”—but with a huge drawback. SSM matches schools to each other based on observable student characteristics, such as the percentage of students receiving free and reduced-price lunch and their racial composition. However, it does not account for unobservable or immeasurable factors like parental support, student motivation, or natural scholastic ability.

This is a huge problem, as there is strong evidence that the kinds of students who choose to leave public schools for charters are systematically different from students who do not. Many of these differences are unobservable even with student-level data, and some of them mark charter school students as higher-achieving to begin with (even when they are still back at their public schools). Fortunately, the value-added methodology accounts for these differences; the SSM measure would not.

To see the limits of SSM and the advantages of value-added, consider one example: UC San Diego’s Preuss School. The charter school specifically targets low-income minority students. Indeed, all of its pupils would be the first in their families to go to college. When compared to other schools serving similar student populations, Preuss would seem to be a huge over-performer. Nearly all of its graduates continue on to higher education, and Newsweek has named it the top transformative school in the country for three years in a row.

As researchers showed a few years ago, however, the reality seems to be far more nuanced. Because of the school’s popularity, it regularly attracts more applicants than it has space to admit, and must use a random lottery to decide which students get accepted. Thanks to this lottery, we have a natural “control group”—children who applied to attend Preuss but lost the lottery—against which to compare its achievement. And when researchers did this, they found few significant differences in achievement between those who attend the school and those who apply but are turned away.

How could this be? It seems to be that the school’s application process (students must complete essays and solicit letters of recommendation, and their parents must agree to at least fifteen hours of volunteering at the school) weeds out all but the most motivated students with plenty of support at home, precisely the kinds of students who are likely to do well academically in almost any school setting.

To be sure, the lottery research also finds that there are real advantages to attending the Preuss School. Its students are more likely to complete classes necessary for college admission and to pursue higher education at higher rates. But few of these benefits seem to be driven by an improvement in actual student learning or achievement in the classroom. This important reality is obscured using the SSM metric, but would show up clearly with value added.

Adding the SSM metric to Ohio’s state report cards would represent an improvement for grades and subjects where value-added measures don’t exist, or for other outcome measures, such as graduation and attendance rates. But it would be wrong to use SSM to simply replace value added for accountability purposes.

Of course, it should be obvious why some charter operators would prefer that the SSM measure be used instead. But it is disappointing that policymakers are considering going along with this. It would be like abandoning high-speed, fiber-optic Internet to go back to the days of dial-up. Let’s not go backward.

Vladimir Kogan is an assistant professor of political science at the Ohio State University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California, San Diego.