Choice, Information, and Constrained Options: School Transfers in a Stratified Educational System

Ohio should set the bar at “college- and-career-ready”

A solution to Ohio’s course access problem

Choice, Information, and Constrained Options: School Transfers in a Stratified Educational System

Welcome back, Jamie Davies O’Leary

Progress and problems: Checking in on the Cleveland Plan

Text of testimony given before the Ohio Board of Education 9/15/15

Ohio should set the bar at “college- and-career-ready”

At this week’s meeting of the state board of education, board members accepted Ohio Department of Education (ODE) recommendations on cut scores that will designate roughly 60–70 percent of Ohio students as proficient (based on the 2014–15 administration of PARCC). While this represents a decline of about fifteen percentage points from previous years’ proficiency rates, it isn’t the large adjustment needed to align with a “college-and-career-ready” definition of proficiency. In fact, this new policy will maintain, albeit in a less dramatic way than before, the “proficiency illusion”—the misleading practice of calling “proficient” a large number of students who aren’t on-track for success in college or career.

The table below displays the test data for several grades and subjects that were shared at the state board meeting. The second column displays the percentage of Ohio students expected to be proficient or above—in the “proficient,” “accelerated,” or “advanced” achievement levels. The third column shows the percentage of Ohio students in just the “accelerated” or “advanced” categories—pupils whose achievement, according to PARCC, matches college- and-career-ready expectations. The fourth column shows Ohio’s NAEP proficiency, the best domestic gauge of the fraction of students who are meeting rigorous academic benchmarks.

Under these cut scores, Ohio will report proficiency rates that continue to overstate the proportion of Ohio students who are on track. This is crucial because proficiency is widely reported in the media, leading many to believe that students are generally doing just fine. On the other hand, the accelerated-plus rate isn’t likely to be emphasized in the media or reported to parents, even though it is the college- and career-ready level defined by PARCC. This rate is also more in line with NAEP results (certainly in ELA, though a bit harsh in math).

Source: Ohio Department of Education Note: The PARCC results are preliminary and based only on students taking computer-based exams. Approximately three in five students took online exams.

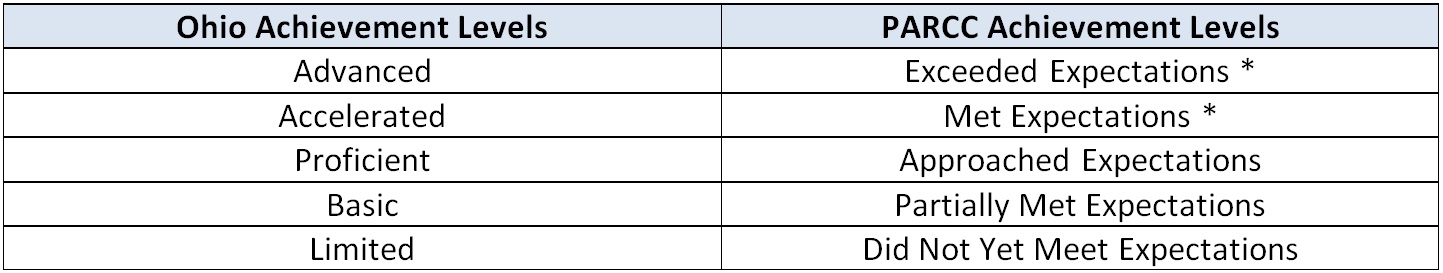

Before casting stones at the State Board or ODE for “lowering standards,” bear in mind that they were constrained by state law, which prescribes five achievement levels—each of which has its designation enshrined in law (ORC 3301.0710). The table below displays a crosswalk between Ohio’s and PARCC’s achievement levels. (The asterisk denotes the PARCC achievement level that corresponds to being on-track for college or career.) As you can see, under present law, there was no simple way the state board or ODE could have aligned the state’s proficient category with the college-and career-ready achievement levels set by PARCC.

The state board has made its call regarding 2014–15 cut scores. But what can the state do moving forward to end the proficiency illusion? Here are three ideas that policymakers should consider, keeping in mind that some of them may take legislative action to implement:

1.) Eliminate the accelerated designation and replace it with proficient; then, replace proficient with another achievement-level identifier, such as “approaching.” In this scenario, the achievement levels would be: advanced, proficient, approaching, basic, limited.

This proposal would ratchet up the meaning of “proficiency” by moving it to the second-highest achievement category—one that could be the threshold for college and career readiness. Indeed, an arrangement such as this would have enabled the state to align its proficient category with PARCC’s college- and career-ready performance levels. While Ohio won’t administer PARCC moving forward, this structure could be adopted when the state shifts to ODE/AIR-designed exams.

2.) Retire the current achievement-level descriptors (e.g., proficient, basic) and move to a “level” or “star” system. The state could define that Level 4 and Level 5, for example, indicate college and career readiness. This idea would allow for the creation of a clearly recognizable benchmark without the legacy of “proficient.” In essence, this would represent a fresh start for communicating student achievement to parents and the public.

3.) Make crystal clear which achievement level equates to meeting the college- and career-ready targets. The Ohio Department of Education, for example, should ensure that schools send home test score reports that plainly tell parents whether their children are on the college-and-career track. (For the 2014–15 year, it would be students designated at or above the accelerated level.) Of course, this suggestion applies to any performance-level structure, including the one that the state board approved this week. Worth considering as a template is this exemplary student test-score report.

As for the 2014–15 test results, proficiency won’t have much to do with college and career readiness. That’s disappointing news, as it contradicts Ohio’s stated goal of transitioning to higher standards. Moving forward, state policymakers should stop dancing around this issue and give the information needed on whether students are meeting benchmarks that set them on the surest track for success in their later lives. The rest of the nation is moving in that direction, and so should the Buckeye State.

A solution to Ohio’s course access problem

In a previous post, I explained course access and its potential to revolutionize school choice in Ohio. The best example of this is the Florida Virtual School (FLVS), which Brookings evaluated in 2014. But Ohio wouldn’t have to copy Florida’s entire model. Instead, it could create a unique one complementing its successful CTE and College Credit Plus programs. While there are plenty of ways to get to the mountaintop, here are a few ideas for how Ohio could establish a pilot program that—if it successfully meets the needs of students—could be grown into a statewide program.

Governance

FLVS was created as the nation’s first statewide, Internet-based public high school. Students can enroll full-time, but approximately 97 percent of students are part-time. Students who are enrolled at a traditional school (district, charter, or private) can sign up part-time for a course for a multitude of reasons: to make up course credit, to take a class not offered at their schools, or to accelerate their learning. Just imagine the possibilities for schools that want to incorporate mastery grading or competency-based education!

To provide Ohio students with similar options, policymakers in the Buckeye State could create a virtual “school” that houses dozens of courses from many providers. Instead of enrolling students full-time, as existing online schools already do, or charging students and families hundreds of dollars per course (which is what many ilearnOhio courses cost), this organization would offer Buckeye students free online courses to complement the work of their full-time schools. Policymakers could choose to run this organization through the Ohio Department of Education or establish an independent but state-accountable body to oversee its operation. The overseeing office would be responsible for managing the site, recruiting and approving the providers who offer courses, evaluating the performance of providers, and delivering status reports to legislators and the state board.

Free is the key word here, because if courses aren’t free, they’re not truly available for thousands of low-income students like those I used to teach. In Ohio, CTE and College Credit Plus are free as long as the participating student selects a public college. Many online courses through ilearnOhio are not—thus the need for a separate type of “school” that houses free online courses instead of “fee-based” online courses. This is what will make the final part of a course access policy—online courses—such a hard sell: Districts won’t want to hear that they’re required to allow students to sign up for courses, and they really won’t want to hear that they’re going to have to pay a fee for each course. They won’t like that the state—not the district—will get to determine the maximum number of classes a student can sign up for (otherwise, districts would be able to cap the maximum number at one or even zero). The fact that the state will not require students to take an online course for graduation will offer little consolation.

But if money is the catalyst for knee-jerk anger, districts should remember that the money spent on course access will be chump change compared with what it costs a school when a student transfers somewhere else. For the dozens of schools that complain about losing students to open enrollment, charters, or private schools, course access would be a lifeline. Offering more and different classes that can be personalized for individual learners—without losing students and at a fraction of the price that it would cost to offer them in person—is in the best interest of districts and students.

Nevertheless, the overseeing office can ensure buy-in from districts by emphasizing potential solutions. Does a district have a ton of gifted high-achievers who need to extend their learning? There are courses for that. Does a graduating senior love the charter he’s enrolled in, but need a few more credits in order to meet graduation requirements? There are classes for that too. Does a rural or urban district want to offer foreign languages or more electives, but can’t afford the expense of hiring teachers, purchasing curriculum and textbooks, or finding a place to house the class? Ditto. Does a suburban district want to offer more AP classes without having to ensure that they recruit a minimum number of students to enroll—potentially leading to students who aren’t ready for AP being in AP? There are courses for that too. Districts save money they’d lose when kids transfer, parents and kids get the classes they want, and the overseeing office holds course providers—not districts—accountable for results.

Funding

Since this new and improved version of online course access would begin as a pilot program, it makes sense for it to be classified as a funding proposal in the budget, similar to the way that competency-based education or the Straight A Fund started. This initial funding would allow for the creation of an overseeing office, the construction of a site, and the recruitment of providers with track records of past success. All education expenses would be funded through deductions from districts and charter schools whose students participate in the program. The district would pay a flat fee per student, per course, only paying for what students actually use and not what districts predict will be used. Since school funding always generates some controversy, policymakers should investigate how other states charge for course choice to see if a better mechanism might be available. For instance, some charge a certain percentage of per-pupil funding, while others use only state funds. (See here for more details).

Providers would receive an initial payment when students enrolled. However, the majority of the payment would be withheld until the student successfully completed the course. This is a form of academic accountability, but it would also ensure that state and local dollars are spent only on effective education. Many course access programs in other states also include a performance component related to funding. Eventually, the state could offer bonuses and incentives to providers who ensured high scores, consistently high completion rates, and parental or student satisfaction.

Accountability

The most important aspect of Ohio’s virtual course access policy is that it leads to student achievement and growth. To ensure that students are completing courses and learning the necessary content, accountability measures must be put in place. Many states with course access include accountability systems (Louisiana’s measures are particularly interesting). As always, the trick will be having sufficient accountability in place to increase the likelihood of strong student outcomes without constraining the program with bureaucratic red tape. Here’s a look at a few accountability measures that Ohio policymakers should consider including in their plan.

- Course approval: Providers shouldn’t be able to offer courses to schools without first being approved by the overseeing office. The approval process could include an application review, interviews, and perhaps even an additional review by an independent expert panel. Regardless of length, the key is that nothing but the best courses end up being offered to Ohio kids.

- Course review: The overseeing office, ODE, or an independent board should complete a structured review of the content of each course. Reviews could be conducted by Ohio teachers and content experts and should examine course alignment to state standards, instruction, assignments, assessments, student support, and other details that ensure a positive student experience and academic success.

- Stakeholder satisfaction: Surveys of parents and students should be conducted each year. The results from these surveys should be part of public accountability records, included in legislative reports, and made available online. (For an example of FLVS survey results, see here).

- Academic accountability: Just like schools and CTE programs are subject to report cards, online courses offered via course access should be subject to public accountability. Although course access report cards may not include all the same components as Ohio’s current school report cards, they should include course completion rates, end-of-course assessment results, and AP assessment results when applicable.

- Financial accountability: Budgets and expenditures should be posted online and independently audited (see here for examples of FLVS annual financial reports).

- Yearly legislative reports: Each year, the overseeing office should compile and deliver a report for state legislators and the state board of education. This report should include course review data, stakeholder satisfaction data, budgets, and academic results. (See here for an example of an FLVS legislative report).

***

Although Ohio already has two components of a solid course access policy—CTE programs and the College Credit Plus program—the online course component is still missing. While many people are hesitant to put their trust in online learning, there is evidence that when implemented well, online course access can take school choice and student learning to the next level. Policymakers in Ohio should consider a pilot project that investigates the potential of online course access—while being careful to ensure accountability in the process.

Choice, Information, and Constrained Options: School Transfers in a Stratified Educational System

In the fall of 1996, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) implemented a new accountability system that placed 20 percent of its schools on “probation.” Poor reading test scores made up the sole criterion for censure and those scarlet-lettered schools were plastered on the front page of both Chicago newspapers. A new study by Peter Rich and Jennifer Jennings of NYU takes a look at enrollment changes in these “probation schools,” both before and after the imposition of the new accountability system. The authors attempt to determine if the addition of new information (“this school is not performing up to par”) motivated more or different school change decisions among families.

1996 may seem like ancient history to education reformers, but the study illustrates the perennial power of information to motivate school choice decisions. In 1996, CPS had (and still does) an open enrollment policy that allows any family to choose any school in the district other than their assigned one, provided there is space available. Since the district provided no transportation to students either before or after the policy was imposed, that issue was moot. The number of schools and seats within the district also stayed the same. In other words, access to buildings remained unchanged after implementation of the probation system. The study’s methodology also controlled for the effect of other accountability-related tweaks that CPS made at the same time. The sole variable under study was the provision of information.

The new information was simple and binary. Schools were either on probation for poor reading scores, or they weren’t: no gradations of bad or good, no value-added information, and only minimal ideas of what changes would be made to try to improve the schools on probation. It was a far cry from today’s report card data extravaganzas and “scary” talk of automatic closure and parent triggers. The only new piece of data for CPS families in 1996 was the big red X of probation.

So what happened in light of this new information? Kids left probation schools in higher numbers after the probation designation than before it. Students attending schools that were placed on probation had 19.3 percent higher odds of transferring schools and 16.1 percent higher odds of leaving the district altogether in the summer following initial assignment. Unsurprisingly, higher-income students were more likely to leave the system—the researchers suppose that they went to private schools, but heading for the ‘burbs is just as likely.

Those students who stayed in CPS and moved from a probation school were no more likely to end up in non-probation schools (i.e., to upgrade) after the policy was implemented than before. Keeping in mind that the difference in quality between probation and non-probation schools could be very slim, lateral moves were the predominant result of the alarm set off by the new accountability system.

Does this mean that accountability-based choice was fatally flawed even before the NCLB era began? No, but it does show that a closed system is not the optimal way to go about using that particular tool. Without a mechanism to assist low-income families in leaving a low-performing district just like high-income families can (vouchers, inter-district open enrollment, ESAs), or a plethora of high-quality seats to transfer into (magnets, charters, STEM schools) just like those who can “work the system” have, bad news about school quality is simply bad news. In Chicago in 1996, families heard the alarm and did what they could. The results were not encouraging. In 2015, we know better. Information, options, and access must be part of the same system in order to truly leverage accountability into better outcomes for students.

SOURCE: Peter M. Rich and Jennifer L. Jennings, “Choice, Information, and Constrained Options: School Transfers in a Stratified Educational System,” American Sociological Review (September 2015).

Welcome back, Jamie Davies O’Leary

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is pleased to welcome Jamie Davies O’Leary back into the fold as our senior Ohio policy analyst. Jamie joined Fordham in 2009 after working as a public school teacher and Teach For America corps member. She was both an Education Pioneers fellow (2008) and a Truman Scholarship fellow (2004), and she holds a master’s degree in public administration from Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

During her first sojourn at Fordham, Jamie focused on the teaching profession and on policies impacting teachers, such as teacher evaluations, merit pay, and the Teach For America program (for which she testified before the Ohio Senate Education Committee).

Jamie left Fordham to work in communications and advocacy for the Ohio Council of Community Schools, one of Ohio’s longest-running and largest charter school authorizers. In her most recent role as the council’s chief communications and advocacy officer, she oversaw the delivery of communications to schools, governing boards, and the media. She also managed the organization’s policy and legislative strategies.

The Ohio Education Gadfly welcomes Jamie back to the team, and we look forward to many more incisive blog posts and publications under her byline.

Progress and problems: Checking in on the Cleveland Plan

During the summer of 2012, Governor Kasich signed House Bill 525 into law. The bill, dubbed the Cleveland Plan, implemented aggressive reforms aimed at substantially improving academic performance in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD). The plan focused on four strategies: growing the number of high-performing schools while closing and replacing failing schools; investing and phasing in educational reforms from pre-K to college and career; shifting authority and resources to individual schools; and creating the Cleveland Transformation Alliance (CTA), a nonprofit responsible for supporting implementation and holding schools accountable. Soon after the bill was passed, Cleveland voters approved a four-year, $15 million levy to support the plan.

Soon, the district will need to go back to the voters to renew the levy that passed in 2012. District leaders have been working hard to demonstrate enough progress on their goals to maintain community support, and they’re right that several promising signs of progress exist. But Cleveland has long been one of the worst-performing districts in the country, and incremental glimmers of progress may not cut it for families and taxpayers. One only needs to glance at the comments section of a Plain Dealer article about the district to observe the public’s already faltering faith. In order to answer the question of whether the district has made enough progress to deserve continued community support, it’s wise to investigate both sides of the coin: the progress and the problems. Let’s take a look.

Signs of progress

This June, the CTA released a report on the implementation and impact of the Cleveland Plan that contained some signs of progress. The report uses state letter grades to place Cleveland schools in one of four categories: high-performing, mid-performing, low-performing, or failing. According to these categories, the percentage of students in failing schools has declined from 43 percent in 2010–11 to 35 percent in 2013–14. CMSD’s high school graduation rate also rose to 54 percent in 2012–13, an 8 percent gain since 2010–11. Fewer graduates tested into remedial college courses, and the percentage of CMSD students who met the college-ready benchmark ACT score of 21 increased from 12 percent in 2011–12 to 14 percent in 2013–14. Finally, of the nine CMSD schools labeled high-performing, six were fully enrolled by the start of the 2014–15 school year.

In his annual update, district CEO Eric Gordon asserted that the Cleveland Plan “is working.” While this year’s objective measures are delayed due to state testing transitions, Gordon shared several positive indicators, including better facilities, more parental engagement, stabilizing district enrollment, 750 new high-quality preschool seats, and financial stability. Gordon isn’t the only one who thinks the plan is proceeding successfully. Megan O’Bryan, the founding executive director of the CTA pointed in a recent op-ed to many of the same measures that Gordon and the CTA report highlighted. She also emphasized the “unprecedented collaboration” between the district and high-performing charters. For instance, CMSD received a $100,000 planning grant through the Gates Foundation’s District-Charter compact. The compact has charter and district officials meeting to discuss how they can work together to increase the availability of high-quality seats. Perhaps most surprising, at least to those outside of Cleveland, is that the district actually shares levy funds with high-performing charters that have decided to work with the district.

In a recent edition of The Sound of Ideas, both Gordon and O’Bryan were careful to note that lasting and transformational change takes time. O’Bryan mentioned that although many of the changes to CMSD were sweeping and significant, they were also behind the scenes, and more definitive results are still to come. In particular, she referred to the increasing autonomy of schools. The CTA’s June report echoes her point: As of 2014–15, 48 percent of the district’s operating budget is controlled at the school level—a remarkable rise from the 5 percent in 2011–12. Gordon, meanwhile, noted that the district’s value-added scores have increased from an F to the equivalent of a C.[1] Value-added measures determine how much a student learns over the course of one year, and a C grade—the state’s expectation—implies that students are learning a full year’s worth of content. While meeting the expectation of a year’s worth of learning is a significant milestone for a district that has struggled for a long time, CMSD needs—sooner rather than later—to help its students gain more than a year’s worth of learning in order to catch up.

Although the temporary absence of state report cards could lead some cities to ease off the gas, Cleveland leaders have taken the opposite approach. Earlier this summer, the CTA released its own school quality ratings. In its School Quality Guide, the CTA provides profiles of schools that include performance index, value added, and graduation rates from the previous year’s state report cards, as well as the alliance’s rating of the schools’ current and historical academic performance. The profiles also include reviews of schools from community members, student demographics, student and teacher attendance percentages, and information provided by each school[2] in regards to its mission and philosophy, academic offerings, extracurricular activities, and safety.

Persistent problems

One persistent problem that CTA and district officials face on the road to raising achievement is attendance. During the 2013–14 school year, Cleveland’s 89.1 percent attendance rate was the lowest of all Big 8 urban school districts. That rate has been flat for quite a few years: In 2012–13 attendance was 89 percent, and in 2011–12 it was 90.9 percent. In fact, over the course of the past nine school years, the highest attendance rate has been 92.1 percent—and that was all the way back in 2006–07. When considering attendance percentages, it’s important to remember that they’re not like grade percentages; while 89 percent on a test indicates a B grade, 89 percent attendance means that thousands of kids across the district are missing school each day. Gordon recently told the Plain Dealer that over the past three years, the district has averaged 57 percent of kids missing ten days or more in a year—a worrisome number, considering the Ohio Revised Code defines a habitually truant student as one who misses twelve or more school days and a chronically truant student as one who misses fifteen or more school days in a single school year.

In an effort to combat the problem, CMSD has created a new campaign complete with radio ads, lawn signs, and billboards. Gordon also penned an op-ed to emphasize the importance of regular attendance. The increased emphasis seems to have had an initially positive effect: Attendance on the first day of school was 91 percent, up from 84 percent last year. These numbers will hopefully stay high throughout the year, particularly since Gordon is willing to go the extra mile—including breaking out dances like the Q-Tip—in an effort to remind kids that regular attendance is important. If numbers don’t stay high, though, district leaders need to take a serious look at reshaping their attendance policies.

Attendance and truancy aren’t the only concerns plaguing the district; despite meaningful progress, there is still much to be done academically if the district hopes to meet its goals. For instance, although the number of students in failing schools has fallen, the number of failing schools has actually risen. In addition, the number of students in high-performing schools declined 2 percent between 2010–11 and 2013–14. Unfortunately, this decrease made the district’s recent changes to its high-quality seats goal seem like a lowering of the bar for the sake of claiming progress. While the change actually raised the bar for deeming schools high-performing (they now must have an A or B on value added instead of an A, B, or C), it also led to an adjustment of how many schools were initially labeled high-performing—thus making the goal for tripling the number of kids in high-performing schools lower than the number announced back in 2012. Adding to the tension is the wait for state test results and report cards. CMSD’s report card from last year didn’t show much progress. The district had F grades in K–3 literacy, gap closing, and overall value added, as well as a D in achievement. The prepared-for-success component was particularly bleak: Within the 2013 graduating class, only 1.8 percent of students earned an honors diploma, .3 percent earned an industry-recognized credential, and .6 percent earned a score of 3 or better on the AP exam. In each of these measures, CMSD was one of the three worst-performing Big 8 urban districts.

***

Persisting problems shouldn’t put a damper on celebrating progress, but they should serve as a reality check for just how much work CMSD and the CTA have left to do. While district officials have presented clear data points that indicate progress, that progress may not be happening quickly enough. Nowhere is this clearer than in the consideration of value added: even though the district’s value-added grades improved to Cs over the past two years, a C isn’t enough to help students gain more than a year’s worth of learning—which is the only way the huge number of students in CMSD who are below grade level will ever catch up (a point that Gordon himself is careful to acknowledge). While district officials have every right to preach that reform takes time, they must also remember that the students they serve don’t have the luxury of time. With each passing year, they get closer to graduation, college, or career; it’s hardly too much to ask that their schools prepare them for their futures.

[1] The C grade referenced by Gordon is based on the district’s one-year value-added score, not the official state value-added score, which is calculated on a three-year average. CMSD’s official overall value-added score (the three-year average) from the 2013–14 school year was an F. The three-year average for 2014–15 won’t be available until state report cards are issued.

[2] School-provided information is voluntary.

Text of testimony given before the Ohio Board of Education 9/15/15

NOTE: Chad Aldis addressed the Ohio Board of Education in Columbus this morning. These are his written remarks in full.

Thank you, President Gunlock and state board members, for giving me the opportunity to offer public comment today.

My name is Chad Aldis. I am the vice president for Ohio policy and advocacy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, an education-oriented nonprofit focused on research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

One of the major strands of our work involves support for school choice, and that’s why I’d like to talk with you this morning about charter schools. Before I begin, and in the interest of full disclosure, I would like to note that Fordham’s Dayton office currently sponsors eleven charter schools around the state.

We believe that charter schools can make a huge positive impact in the lives of kids, and in many places around the country, they already are. It has become increasingly clear that while Ohio has many outstanding charter schools, the state’s laws must be strengthened if our charter sector is going to match the success being realized elsewhere. This past year, to achieve that goal, we’ve sponsored two major pieces of research, offered public testimony, worked with the media, and educated legislators on the importance of reform.

As I’m sure you know, thanks to the many hard-working reporters and editorial boards around the state, the legislature has a very strong bill (HB 2) that has already passed the Senate unanimously and is ready for consideration by the full House. I’m optimistic that the bill will pass this fall. But, I’m here this morning to tell you that the passage of that legislation alone won’t be enough to improve charter school performance.

All of you, more than most, understand the importance of implementation if legislation is going to have its desired impact. Without strong implementation, a good bill adds up to little more than words on paper. Consider the recent controversy over whether to include student achievement in online charter schools as part of the academic component of the sponsor evaluation system. I’ll state what you already know. The grades, of course, should have been included. Beyond the law, the underlying principle is even more important: Strong accountability demands that, whenever possible, every student in every school should count.

Here’s where my remarks will likely differ from others that you’ll hear today. From everything I’ve seen, the situation that led to Mr. Hansen’s resignation is the exception rather than the rule. Over the past two years, in fact—and for the first time in my memory—ODE has taken its responsibility to charter schools seriously.

I’m not a fan of empty rhetoric. Here’s what I mean when I say that the department has stepped up its charter school oversight:

- In October 2013, State Superintendent Ross ordered the immediate closure of two schools in Columbus for egregious health and safety violations.

- In April 2014, ODE warned three sponsors against opening new schools due to outstanding judgments against directors, problems with their application and review processes, and concerns about school “recycling.”

- Also last year, the department took unprecedented steps to make sure that VLT Academy in Cincinnati closed permanently, without being able to change names and resume business as usual, after being dropped by its sponsor.

- Just three months ago, the department gave notice to four schools (which it had inherited from a failed sponsor) that they’d be closed at the end of the school year for a pattern of poor academic performance, among other reasons.

- Finally, the much-discussed sponsor evaluation system—which Fordham has gone through and found to be rigorous but fair—seems to be making sponsors think carefully when considering whether to open new schools; the number of new charter schools this year was down dramatically from past years.

These are significant actions that the department has taken in the past few years to improve Ohio’s charter school sector. I think it speaks to this administration’s view that charter school performance matters.

Going forward, it’s critical that the department:

- Continues its strong recent enforcement of Ohio’s charter school laws; for too many years that didn’t appear to happen

- Quickly and thoroughly implements any charter school provisions passed in HB 2

- Completes the recently instituted independent review of the sponsor evaluation system and quickly returns to evaluating sponsors (sponsors are the lynchpin of our charter accountability system, and while the academic portion certainly needs review, the measures dealing with compliance and quality practices were developed in conjunction with national experts and appear to be of high quality)

- Ensures that the Office of Quality School Choice is staffed sufficiently to meets it statutory and administrative duties

Thank you again for the opportunity to speak with you today. I am happy to answer any questions that you may have.