Expecting more of our gatekeepers of charter school quality

Sponsors can and must avoid opening charter schools destined to fail

Sponsors can and must avoid opening charter schools destined to fail

The Akron Beacon Journal recently reported on the struggles of Next Frontier Academy, a charter school whose failures have included incomplete student records, missing funds, inflated enrollment figures, an inability to make payroll and rent, and student-on-student (and student-on-staff) violence that went unreported to the police. This type of educational malpractice ought to make everyone angry—especially charter school supporters and allies. Mercifully—for its forty students and Ohio’s taxpayers alike—the school closed this summer.

The closure isn’t an anomaly in the Buckeye State. Since the charter school movement’s inception in 1997, over two hundred schools have shut their doors. According to the Beacon Journal, “more charter schools closed last year than at any point in the industry’s seventeen-year history in Ohio.”

Closure isn’t necessarily a terrible thing. It certainly isn’t proof that the movement has failed, as some critics suggest. Charter schools that are under-enrolled, financially unstable, or academically deficient should be closed. This feature sets them apart from traditional public schools that stay open forever regardless of performance, and it should be embraced. Moreover, evidence suggests that students are the winners when low-performing schools are closed, despite the initial disruption and inconvenience that may occur. A Fordham study from earlier this year showed that students made significant gains in both math and reading after their schools closed.

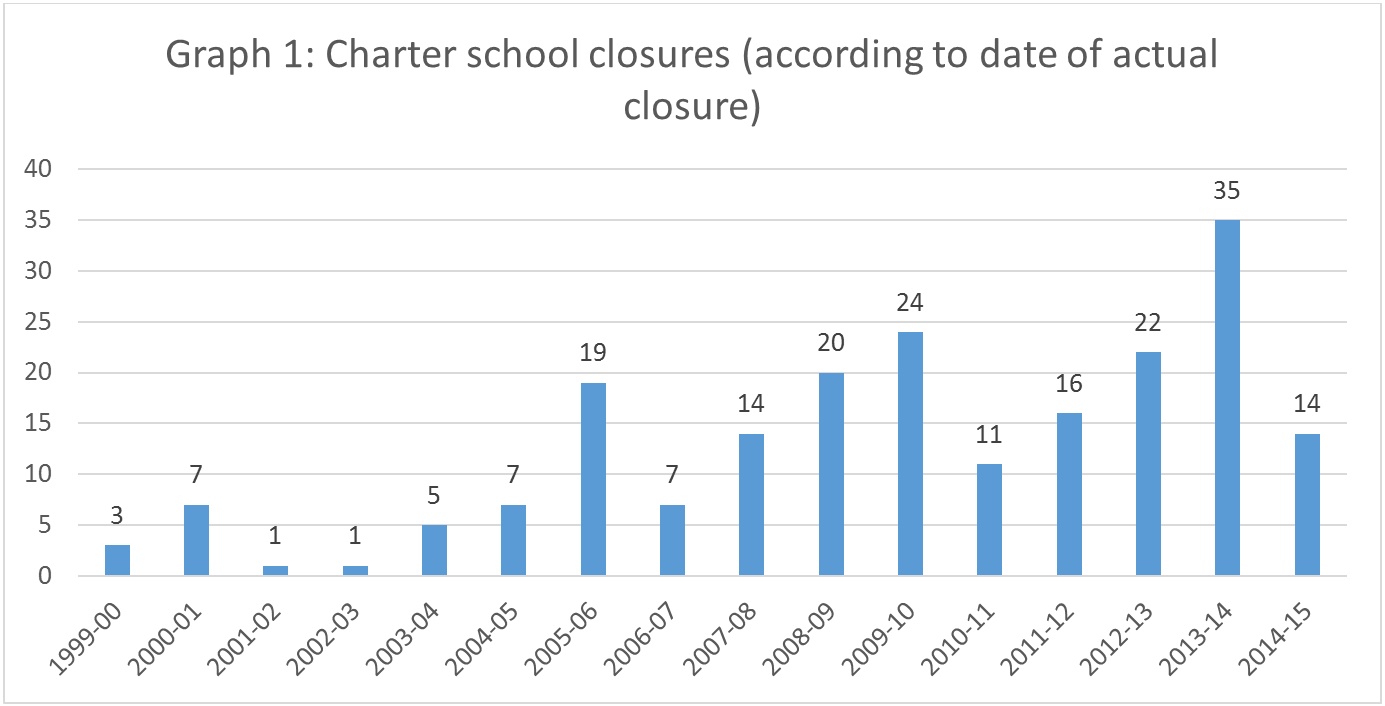

Still, widespread closures are alarming and deserve further exploration. Data from the Ohio Department of Education[i] confirms that the 2013–14 school year (the most recent one for which complete data are available) set an unsightly record: Thirty-five charter schools closed up shop. By our count, this means that 17 percent of all closures in the movement’s history occurred in a single year.

Ohio has an automatic closure law that requires charter schools to shut down if they chronically underperform. Further, the state has ramped up efforts to hold charter school sponsors (a.k.a. authorizers) accountable for their schools’ academics. It therefore makes sense that Ohio is experiencing higher numbers of closure during the more recent years of the movement’s history (as depicted by Graph 1). While thirty-five closures in one year is somewhat shocking, the trend laid out in Graph 1 overall is not.

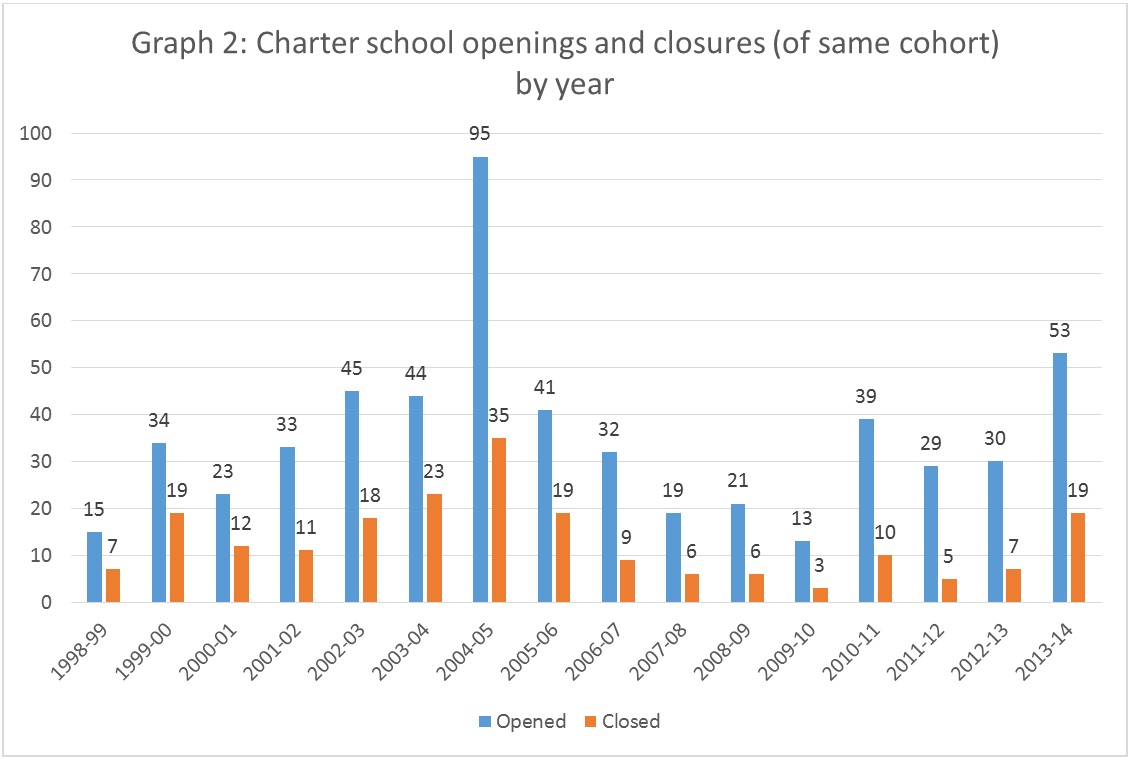

Graph 2 (below) attempts to shed light on the closure rates of charter schools based on the year they opened. In other words, of all schools that opened in a given year, how many have closed—regardless of what year in which the closure took place? Examining school openings and closures by yearly cohort adds context. Which years experienced the highest rates of opening, or the highest rates of closure? How successful was each group of start-up charter schools (with success being defined narrowly as the ability to remain open)?

For example, three schools that opened in 2009–10 ended up closing, but only thirteen in total opened that year—an overall success rate of 77 percent. 2011–12 had the highest success rate (83 percent): Twenty-four of the twenty-nine schools started that year remain open today. Conversely, only 44 percent of schools started in the 1999–00 school year are still around, but those nineteen schools may have closed at any point in the last fifteen years.

In contrast, nineteen start-ups from the 2013–14 school year alone have already closed. And that’s based on data that only provides information up to 2014. Once 2015 information is added in, that number will likely be higher.

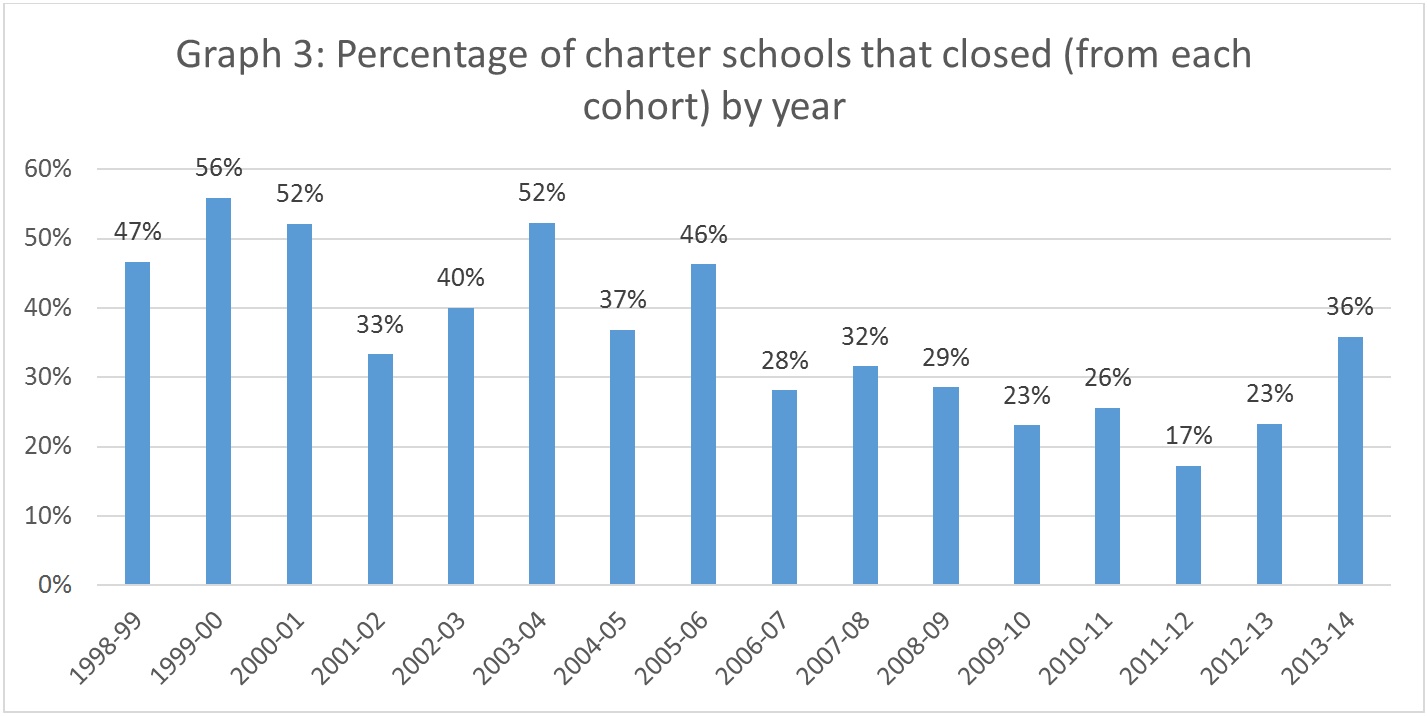

Graph 3 shows the closure rates of charter schools by yearly cohort, with 2013–14’s group of start-ups experiencing the highest closure rate in nearly a decade (36 percent).

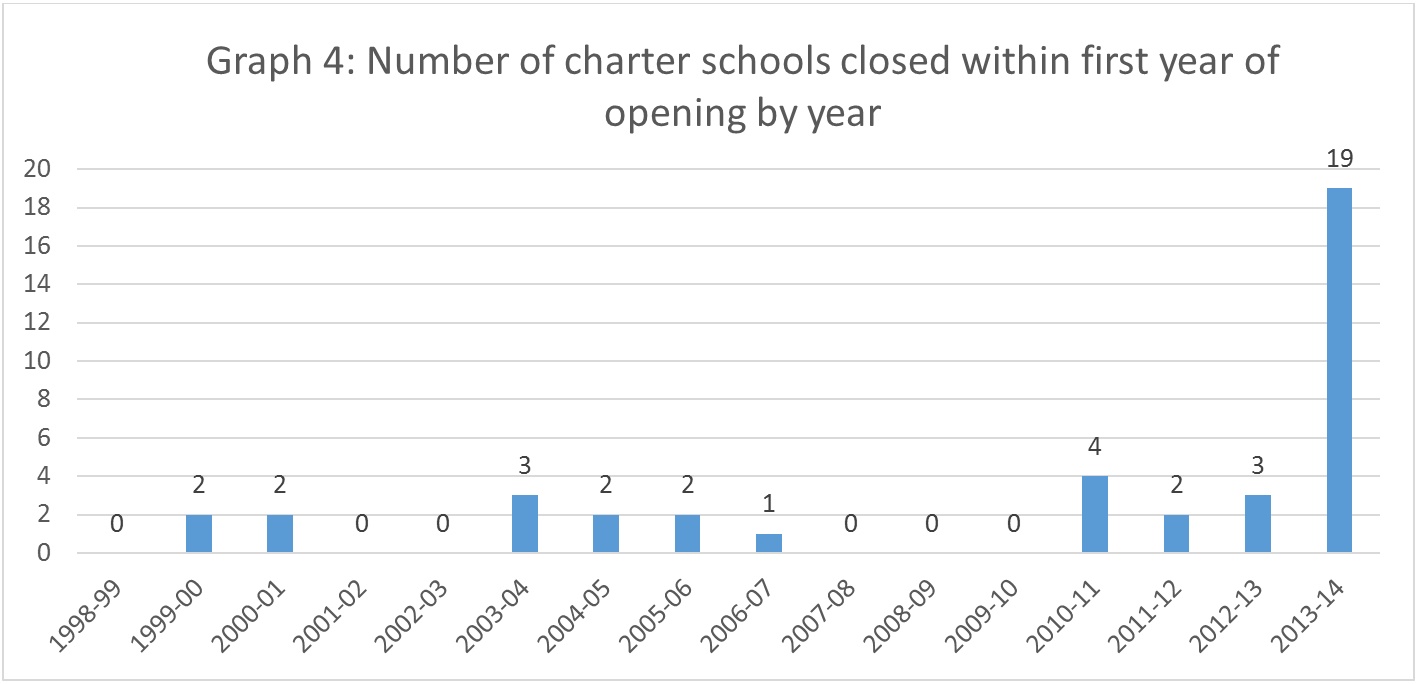

Graph 4 illustrates just how radical 2013–14 was, with an unprecedented number of first-year start-up failures. Nineteen schools that opened in 2013-14 were closed mid-year or by the conclusion of that school year, five times as many first-year failures as Ohio had ever witnessed.

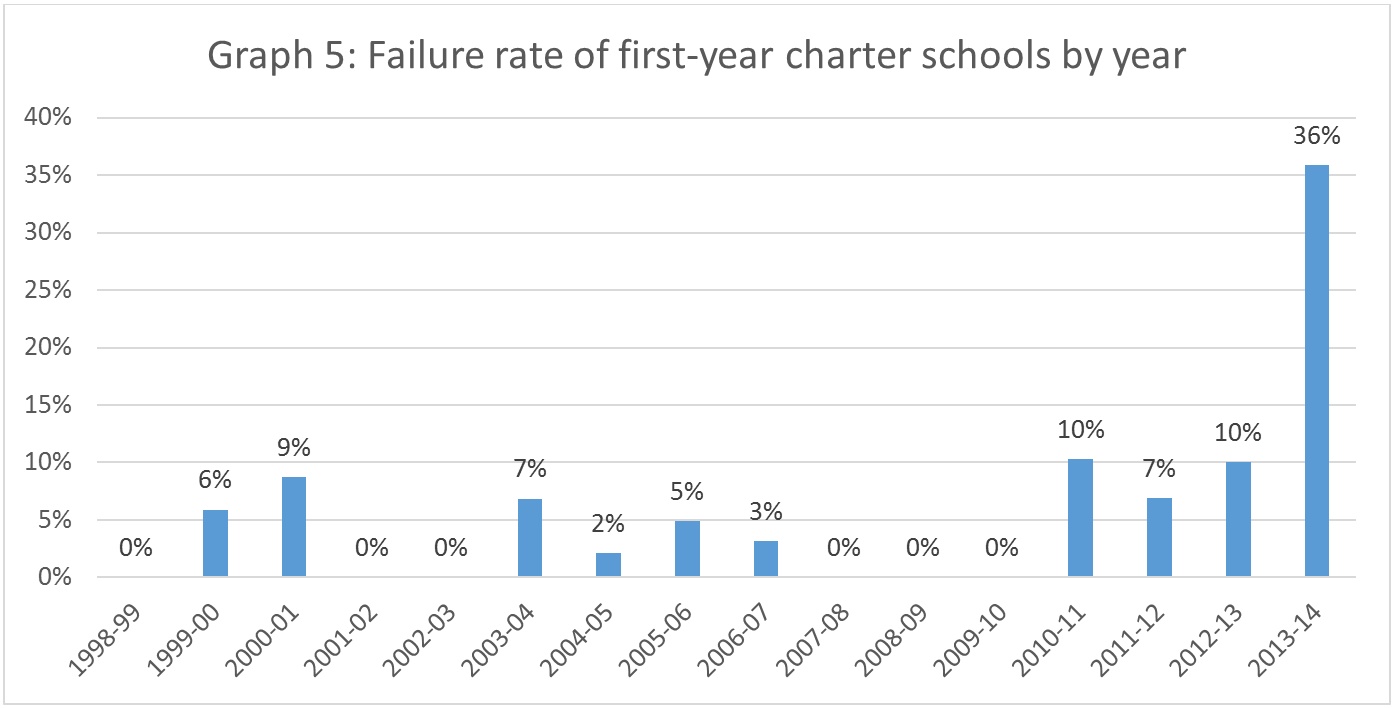

Graph 5 tells the same story: As a percentage, 2013–14 far surpassed all others in its overall failure rate of first-year charter schools.

Some might argue that widespread closures are proof that charter school overseers—governing boards and sponsors—are doing their jobs. Don’t the relatively high number of closures from 2013, 2014, and 2015 (Graph 1) illustrate that Ohio’s emphasis on quality oversight is working?

Partially, yes. The vast majority of closures (all but twenty-four) in the past decade and a half were “voluntary” or “sponsor-ordered” rather than triggered by the automatic closure law. Governing boards and sponsors are deciding to shut down charter schools that are no longer academically effective or financially viable, as they should. Closing a charter school is no easy task as the Fordham Foundation’s authorizing department can attest. So kudos to anyone who has played a role in closing an ineffective school.

But as Graphs 2, 3, 4 and 5 illustrate, quality oversight is not in place in all phases of a charter school’s life cycle. Widespread failure like what occurred from 2013–14 points to a glaring problem with how sponsors vet and open new schools. That’s an equally (if not more) important component of oversight. A sponsor is the gatekeeper of quality at its school’s inception. It conducts due diligence on new school applicants, examines their track records (and, one hopes, their criminal records and bank accounts), and uses value judgments regarding which schools it thinks will ultimately succeed or fail.

We must expect more from these gatekeepers. Closing poor performers when they have no legs left to stand on is only a small part of effective oversight. A far better alternative would be to prevent them from opening in the first place. Sponsors don’t have to be soothsayers to predict failure where prospective applicants have failed before, or where they lack the funds or expertise to run a school. The bottom line is that when a closure happens in the first year or two of operations, there were usually warning signs; if heeded, those signs should have kept the school from ever opening. If Ohio charter schools are going to improve, better decision making about new school applicants will be critical.

After a record-breaking year for closures and public debacles on the sponsoring front, Governor Kasich and the Ohio House and Senate have come to the same conclusion. This past spring, sponsor accountability was a centerpiece in each of their respective charter school reform plans. House Bill 2 puts in place several reforms to reward high-performing sponsors and minimize perverse incentives embedded in the current system. If passed, HB 2 would only allow quality sponsors to open new schools. The bill also prohibits sponsors from selling services to the schools they oversee and places strict parameters around schools wishing to find a new sponsor.

Sometimes sponsors will get it wrong, and that’s okay. By nature, charters were designed to offer innovative alternatives, and Ohio can’t spur innovation unless it’s willing to tolerate some degree of risk. The state recently won a federal Charter School Program (CSP) grant that will inject $71 million into the sector. Ohio should use this money to help excellent schools replicate and recruit high-performers. The reforms in HB 2 are necessary to ensure that we manage the risk of opening new schools much better than we have in the past, a responsibility—and opportunity—that is amplified by the infusion of CSP funds. Never again should nineteen schools start and stop within the same year. As a sector, we can and must do better.

While plenty of folks seem to think that getting rid of Common Core would be good for schools, the standards remain largely intact in most states across the nation, including here in Ohio. Before supporters start congratulating each other on victory, however, they would be wise to recognize that the real battle for Common Core has just begun. As my colleague Robert Pondiscio points out, “far too little attention has been paid to the heavy lift being asked of America’s teachers—and the conditions under which they are being asked to change familiar, well-established teaching methods.”

This heavy lifting includes selecting curricula to teach the standards (because the standards aren't a curriculum—districts choose their own). The lift gets Atlas-like when one considers the poor alignment of the curricula from which districts and teachers can choose. Since last summer, researchers have called out textbook publishers’ misleading claims of alignment with words like “sham,” “buyer beware,” “disgrace,” and “snake oil.” Slapping “shiny new stickers on the same books they’ve been selling for years” has probably lined some pockets, but it’s also left teachers high and dry—and still hefting the weight of ensuring that students master more rigorous standards.

Ohio teachers are no exception. In early September, the Columbus Dispatch wrote about how difficult it’s been for Ohio districts to find high-quality, Common Core-aligned textbooks. An instructional coach from Hilliard City Schools told the Dispatch that a “consultant from the state” recommended that they create their own materials instead of purchasing textbooks. If you think creating material from scratch sounds like a lot of extra work for teachers, you’re right. But even though the phrase “create their own materials” brings to mind the terms do it yourself, teachers don’t actually have to start from scratch. There are plenty of good jumping-off points. EngageNY already has a complete, free curriculum from pre-K through twelfth grade in both ELA and Math.[1] The Open Educational Resources Commons has an extensive library of free teaching and learning materials, also from pre-K through twelfth grade (and beyond). Sites like Teachers Pay Teachers, Share My Lesson, and Better Lesson feature Common Core-aligned lessons written and rated by other teachers. Though some lessons and units on these sites must be purchased, the price is far lower than that of many traditional supplemental materials. Teacher collaboration is also a valuable, if underused, resource. When teachers are given the chance to share their strengths and ideas, everybody wins. Most importantly, though, all these resources can be mixed and matched to create an adapted, customized curriculum that’s better than an off-the-shelf one.

Although personnel costs make up the lion’s share of school budgets, textbooks are expensive. McGraw-Hill lists one of its biology textbooks at $116 and one of its Algebra I textbooks at $108. Prentice Hall’s tenth-grade literature textbook is $90 per student edition, and an additional $143 for the teacher’s edition. Its American government textbook rings in around $80 per student edition and $115 per teacher’s edition. When districts consider how many students they have, how many classes—and thus textbooks—they’ll need, and the additional cost of teachers editions, they end up with sticker shock—and that’s before they realize that textbooks in subjects like history and science can get dated pretty fast and need replacing. Similarly, many teachers find that one textbook won’t cover all that their students need to know; workbooks, supplemental materials, and other resources help get the job done, but bring additional costs. For the record, this isn’t a new, Common Core-related problem. Teachers and schools have coughed up money for additional materials for decades. But while Common Core didn’t create this problem, it may have created the solution. Teacher-created materials are a powerfully disruptive innovation because when curriculum is designed instead of purchased, costs can drop.

But money isn’t the only reason why investing in teacher-created materials might be better than investing in textbooks. When teachers use their expertise and experience to design curricula, local control becomes a reality instead of an empty mantra. Teachers are empowered to put not only their content knowledge to work, but also their knowledge of their students’ strengths, weaknesses, and interests. Instead of racing to get through a predesigned curriculum, teachers can adjust the pace as they go. Instead of giving pre-made tests that don’t return meaningful data, teachers can design assessments that test multiple things in multiple ways. A 2014 Fordham study found that districts that utilize homegrown materials enjoy more buy-in and ownership from teachers—which is crucial to making any set of standards, not just the Common Core, successful.

Despite these positive elements, the fact remains that creating a curriculum is a whole lot of work. Time is limited for teachers—how can we justify putting more on their plates simply because publishing companies decided to make money instead of high-quality materials? There’s also the additional worry that not all teachers are up to the task of creating high quality, homegrown materials. This is where schools must step up and declare their commitment to investing in teachers. If leaders want locally adapted curricula that will help their students meet the high bar of the standards and aligned assessments, they must require two things: First, they must put highly effective teachers with proven track records in charge of creating materials, and second, they must give these teachers time and training.

The highly successful charter network YES Prep does this extraordinarily well and could serve as a model for any school interested in homegrown curricular materials. One of the many ways they develop teacher leadership is by selecting highly effective[2] teachers to become content specialists and course leaders. These teachers are assigned a reduced course load in order to create exemplary lesson plans, materials, and assessments that are used by other teachers in their content area. YES Prep’s extraordinary results should speak to how successful this model is, but I can also offer anecdotal evidence: This is the model I experienced as part of the Achievement School District. As a course leader, I was a hybrid teacher who was given the freedom to teach. For the first time, I was able to ditch the expensive (and useless) textbooks that I’d been asked (read: forced by my previous district) to teach to my students who were grade levels behind and needed way more than that particular textbook could offer. I was given extra time to make it happen and extra pay to compensate my hard work, but it was the freedom that mattered. I was empowered to use Common Core and dozens of open educational resources to revolutionize English class for my kids. But the most revolutionary aspect of my time as a course leader wasn’t the extra time and extra pay or even the freedom; it was actually the professional development (PD) I received. Course leaders like me received dozens of hours of professional development that focused on how Common Core was different from previous standards, how to write long-term and short-term plans, how to break a standard into objectives, how to select a text, how to craft a good assessment—the list goes on. For the first time in my career, I got personalized development and immediate feedback, and it made all the difference.

If Ohio districts want to tap into the potential of teacher-created materials, they’ll need to do more than provide time—they’ll also need to provide quality professional development. Teacher PD is notoriously bad; now, with higher expectations and better accountability, the need for high-quality PD is even greater. The money districts will save by opting for homegrown materials should go toward training teachers in how to create, adapt, and improve curricula. Just like schools should stop throwing money at the same old publishers offering the same old textbooks, they should also stop throwing money at the same old PD. Ongoing support is the key, and teacher coaching is a good place to start.

While the lack of quality Common Core-aligned textbooks is frustrating, there is a light at the end of the tunnel. Hundreds of highly effective teachers across the state have the content knowledge that can be used to create homegrown materials. But they need the time, training, and empowerment to make this solution a reality. It’s time for districts to stop looking for one textbook to rule them all—and to start investigating how highly effective teachers might adapt and create materials to make an even better curriculum.

In Eastern Ohio and elsewhere across the nation, fracking has had a profound effect on economic activity and labor markets. But has it had an impact on education? According to a new study by Dartmouth economists, the answer is yes: The proliferation of fracking has increased high-school dropout rates—and not surprisingly, among adolescent males specifically. They estimate that each percentage point increase in local oil and gas employment—an indicator of fracking intensity—increased the dropout rates of teenage males by 1.5–2.5 percentage points.

The analysts identify 553 local labor markets—“commuter zones,” or CZs—in states with fracking activity, including Ohio. For each CZ, they overlay Census data spanning from 2000 to 2013 on employment and high school dropouts (i.e., 15–18 year olds not enrolled and without a diploma). The study then exploits the “shock” of fracking—it picked up significantly in 2006—while also analyzing the trend in dropouts. Prior to 2006, dropout rates were falling for both males and females; post-2006, dropout rates for males shot up in CZs with greater fracking activity. (Female dropout rates continued to decline.) Using statistical analyses, the researchers tie the increase in male dropout rates directly to the fracking boom.

This study raises important issues about the work-school decisions that some teenagers face. In the case of fracking, a fair number have opted into the full-time labor market—arguably a rational decision, at least in the short-run. (For such teens, attending school represents a considerable opportunity cost in light of decent wages.) But what if jobs in the oil and gas fields dry up—what are their options then? Have they sacrificed the longer-term benefits of an education for a short-lived windfall?

Perhaps adolescents shouldn’t have to make a premature choice between school and work. Why can’t they have both? Vocational tracks and specialized schools—like the Utica Shale Academy charter school in Eastern Ohio—offer students an opportunity to gain hands-on experience while earning their diploma. For those with an immediate need of a paycheck, policymakers should consider ways to boost paid apprenticeships or promote part-time employment. However accomplished, young people deserve every opportunity to explore the world of work, without sacrificing academics, during their teenage years.

Source: Elizabeth U. Cascio and Ayushi Narayan, Who Needs a Fracking Education? The Educational Response to Low-Skill Biased Technological Change (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2015)

Fordham, which sponsors (a.k.a. authorizes) eleven charter schools across the state, is proud to see two of its Columbus-area schools and their leaders featured in the news recently.

United Preparatory Academy

Columbus Alive, a weekly alternative paper focused on arts, culture, and entertainment, gave credit to United Schools Network for its work in revitalizing Franklinton, one of the city’s most up-and-coming neighborhoods. Even cooler than the artist lofts, tattoo shops, and hipster-filled farmers’ markets (and arguably more critical to the community’s long-term health), United Schools is providing a high-quality educational option for families living there. United Preparatory Academy (UPrep) opened in 2014 and serves students from kindergarten to second grade, one-quarter of whom come directly from the neighborhood. Columbus Collegiate West—a replication of United’s award-winning Columbus Collegiate Academy, located on the city’s east side—opened in the same building in 2012 and serves students from grades six through eight. UPrep will continue adding a grade each year until meeting up with Columbus Collegiate West to create a K–8 building.

United Schools Founder and Chief Executive Officer Andy Boy recognizes United’s role in long-term community transformation, as the Franklinton Development Association recruits homeowners who are looking for high-quality schools. The problem is not unique to Franklinton: Young people flock to rapidly gentrifying areas, but they flee once they have young children because of the dearth of decent schools. Boy hopes for strategic partnerships and collaboration so that United can help reverse this trend. The arts scene that defines Franklinton offers many natural and enriching partnership opportunities between the community and his network of schools.

This past summer, the Dispatch drew attention to Franklinton in the context of a recent analysis by the D.C.-based Urban Institute. The neighborhood ranked second-lowest in the entire country in a “neighborhood advantage score” (which considered the average household income of each Census tract), as well as the share of people with college degrees, homeownership rates, and median home values.

It seems suitable that a neighborhood characterized by grit would be home to a charter school network whose grassroots climb to success embodies exactly that quality.

KIPP: Columbus

Capital Style recently published a lengthy profile of KIPP Columbus Executive Director Hannah Powell. The article outlines Powell’s journey from Wittenberg University to teaching sixth and seventh graders in Philadelphia via Teach For America, before eventually heading back to Ohio. She was recruited to take the helm at Columbus’s first and only KIPP school, where she successfully boosted enrollment, reestablished KIPP philosophy, closed a budget deficit, and brought much-needed leadership and a relentless commitment to success.

Powell’s vision is as expansive and inspiring as the school’s brand-new campus. She remarked, “The children in our country, only one of ten in low-income homes are making it through college, and that’s an injustice. To address this, it’s going to take everyone working together, relentlessly, to serve kids the way they deserve. It’s going to take, quite frankly, us creating a more just world for our kids.” The magazine also quotes KIPP board member Abigail Wexner on Powell’s role in KIPP’s success: “Hannah [proved to be] tenacious and curious and hardworking. And the quickest study I have ever met.” No doubt, she has played an integral role in establishing one of Columbus’ most successful charter schools and growing it into the program it is today. Powell’s leadership style and emphasis on strong community partnerships—as exemplified by the number of community leaders providing quotes in the piece—are worth emulating.

A blended Advanced Placement (AP) pilot program unfolding in Cincinnati shows tremendous promise. It provides students in poverty with in-person and virtual access to AP instruction and—if successful—could help make the case for why Ohio should provide free and universal access to online courses.

Over the years, Advanced Placement (AP) courses have been one of the most effective ways to prepare high school students for college and make it more affordable—a double win. However, there are enormous discrepancies in students’ access to AP programs based on geographic location, race, and poverty levels. The very academic programs that can help first-generation college goers and those typically underrepresented in higher education tend to be less available to them. Admittedly, some progress has been made: between 2003 and 2013, the number of students taking and scoring a 3 or higher on an AP exam almost doubled nationally. But Ohio continues to lag, not just in overall access to AP, but in successful course completion. The state falls considerably below the national average: 14.8 percent of 2013 Ohio graduates scored a 3 or higher on the AP exam, compared to 20.1 percent nationally.

That’s why an AP program piloted by Cincinnati Public Schools (CPS) is so exciting. The initiative is a blended model that allows one teacher to instruct a larger-than normal group of students in multiple locations (i.e., 130 students spread across four schools). The teacher rotates buildings, allowing the remaining students to follow along online. It’s a wise solution that helps create economies of scale and link students not just to expanded course content, but also to high-quality teaching.

The North Carolina-based research group Public Impact promotes this solution through its “Opportunity Culture” initiative. By extending the reach of great teachers to more students, everyone wins. Teachers earn more money for taking on a higher student load; students benefit from excellent teachers regardless of whether their contact with them is face-to-face or virtual; districts can pocket the savings and also reap the benefits of having more academically prepared students.

The Cincinnati program, still in its infancy, began in the 2014–15 school year with one course offered at seven schools. It expanded to five courses at ten high schools this fall, including one at Withrow University High, a predominantly black school with a poverty rate of 80 percent. CPS deputy superintendent Laura Mitchell said that the new program is about “equity and access.” Prior to the pilot, half of Cincinnati’s schools offered no AP courses, and about two-thirds offered only one course.

Last fall, the Columbus Dispatch dug into similar high school course data, illustrating that geography matters a great deal in determining access to high-level courses in the Buckeye State. (Note that “high-level” included not just AP courses, but International Baccalaureate classes, general advanced courses, and nontraditional languages like Chinese.) The analysis found that suburban districts had over four times the number of high-level courses as rural (and poorer) districts on average (26 versus 6.5, respectively).

Knowing that pervasive disparities exist statewide, Cincinnati’s AP expansion is worth celebrating. But the Cincinnati Enquirer still asks if improved access is enough, especially when gaps remain pronounced: Cincinnati’s award-winning Walnut Hills High School offers thirty-two AP courses to Withrow’s five. This is a Pandora’s-box-opening question in terms of how we define equity and fairness in education (and one best saved for another day). Withrow teacher Kraig Hoover, whose children attend Walnut Hills, offered his thoughts: “Equity is not about taking away from those who have—it’s about building up those who have not.”

So what’s the best way to go about that? Some states, like Arkansas, have mandated universal access to AP. In 2008–09, all schools were required to offer a minimum of four advanced placement courses (and pre-AP courses to boot). Ohio has no such requirements, and many schools have zero AP offerings. However, the state does require that each district participate in the College Credit Plus program, which strives to accomplish AP’s stated goal: access to college-level coursework at no cost.

Given the challenges involved in hiring and retaining qualified teachers to lead AP courses and the small size of many of Ohio’s rural districts, a smarter policy would be for the state to ensure universal AP offerings via a virtual/blended platform. This could be similar to what Cincinnati is piloting at the local level. Florida is a leader in this realm with its statewide, online Florida Virtual School, which offers free courses to all public, private, and homeschooled students in the state (and to students globally for a fee).

As my colleague Jessica Poiner recently pointed out, Ohio is already two-thirds of the way toward a stellar course access policy, with a robust career and technical education (CTE) program and College Credit Plus. But the state is still lacking when it comes to providing access to free online coursework for all students. Ohio should ensure that students can earn credits from courses beyond their own school boundaries using blended and virtual delivery methods. It could go a step further in ensuring that AP courses are among those available, like in Florida. (To consider how Ohio might develop a robust course access policy that includes a virtual platform, read Jessica’s thoughtful follow-up piece here.) And to take a cue from CPS—which gave students participating in virtual AP courses laptops and wifi hot spots—the state must also consider the technological implications of expansion and be prepared to pay for it.

There are no results yet for Cincinnati’s pilot AP program. When there are, students’ completion rates and exam scores will go a long way toward determining how much work we have left to do to prepare Ohio’s students for the rigors of AP. In the meantime, Ohio should guarantee that every student who is prepared for AP has access to it, making it the highest priority in high-poverty and/or rural schools. A blended/virtual solution would be the most cost-effective and scalable way to get there.

Researchers from the National Bureau of Economic Research recently examined whether financial incentives can increase parental involvement in children’s education and subsequently raise cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes. The analysts conduct a randomized field experiment during the 2011–12 school year in Chicago Heights, a low-performing urban school district where 90 percent of students receive free or reduced-price lunch. The 257 parent participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: a treatment group in which parents were paid immediately, a second treatment group in which parents were paid via deposits into a trust fund that could only be accessed when their children enrolled in college, and a control group which received no payment. Parents in both treatment groups could earn up to $7,000 per year for their attendance at parent academy sessions (eighteen sessions, each lasting ninety minutes, that taught parents how to help children build cognitive and non-cognitive skills), proof of parental homework completion, and the performance of their child on benchmark assessments.

To measure cognitive outcomes, the analysts averaged results along the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test and the Woodcock Johnson III Test of Achievement; to measure non-cognitive outcomes, they averaged results from the Blair and Willoughby Measures of Executive Function and the Preschool Self-Regulation Assessment. These assessments were given to students at the beginning of the program and at the end of each semester. The effect of the financial incentive on children’s cognitive test scores was statistically insignificant. The incentive’s impact on non-cognitive skills, however, was larger and statistically significant—approximately .203 standard deviations. Interestingly, in both cognitive and non-cognitive measures, the two treatment groups yielded identical results.

The researchers broke the results down based on race and pre-treatment test scores. In terms of race, Hispanic children (48 percent of the sample) and white children (8 percent of the sample) showed large and significant increases in both cognitive and non-cognitive domains. Black children, on the other hand, demonstrated a negative but statistically insignificant impact on both cognitive and non-cognitive dimensions. The researchers explored several hypotheses for these differences, including the extent of engagement, demographics, English language proficiency, and pre-treatment scores, but could find no “convincing explanations” for the differences between racial groups.

Overall, the results seem to raise more questions than answers. Is $7,000 a year for parental incentives cost-effective? Do the cognitive and non-cognitive gains persist, or do the effects wear off after a few years? And why are there such large differences between racial groups? While parental involvement is undoubtedly critical, particularly for young children, how to genuinely engage parents—particularly those from disadvantaged circumstances—remains very much an open question.

SOURCE: Roland G. Fryer, Jr, Steven D. Levitt, John A. List, “Parental Incentives and Early Childhood Achievement: A Field Experiment in Chicago Heights,” National Bureau of Economic Research (August 2015).