About last week’s “emergency” school levies

Last Tuesday, Ohioans finally voted in primaries for state representative and (if applicable) state senator after the traditional spring primary was delayed due to redistricting issues.

Last Tuesday, Ohioans finally voted in primaries for state representative and (if applicable) state senator after the traditional spring primary was delayed due to redistricting issues.

Last Tuesday, Ohioans finally voted in primaries for state representative and (if applicable) state senator after the traditional spring primary was delayed due to redistricting issues. As might be expected for a summer election with few competitive races, statewide voter turnout was a dismal 7.9 percent.

In addition to primaries, a handful of districts had tax measures on the ballot. In the Dayton Daily News’s election coverage, it noted two such levy requests in the area, one for Ross and the other for Clark-Shawnee. The Ross tax request lost by a 64-36 percent margin, while Clark-Shawnee’s narrowly passed by eleven (yes eleven) votes. By the looks of it, roughly a quarter of voters in those districts turned out. The Ross school board has already said their proposal will be back on the ballot in November.

Ohio’s summer elections aren’t exactly a shining example of democracy in action. The irregular timing discourages participation and results in a small fraction of voters—likely those with the strongest interest in the outcome—holding undue influence. And no one should expect citizens to be plugged into local politics year-round. In a promising move, legislation passed last December by the House would eliminate August elections, including the ability of districts to put tax measures on the ballot during the dog days of summer.[1] The Senate should take up this cause in the coming months.

Not only is the timing quirky, but the type of levy that Ross and Clark-Shawnee proposed is also unusual. In Ross’s case, the district requested a new “emergency levy” that would have raised the property taxes of its citizens. Clark-Shawnee had the same type of levy on the ballot, but it was asking voters to renew two previously approved emergency levies passed in 2012 and 2014. While voters in that district wouldn’t have experienced a tax hike, their taxes would have been cut had they rejected the proposal.

Despite the alarming terminology, an emergency levy is not as ominous as it sounds. It doesn’t require a district to be in an actual “fiscal emergency,” a formal designation declared by the auditor of state that results in a district being overseen by a state commission. In fact, neither Ross nor Clark-Shawnee is in fiscal emergency; they aren’t even in the less-severe distress categories known as “fiscal watch” or “fiscal caution.” According to the Ohio Department of Taxation, 215 school districts—about one in three—imposed an emergency levy in 2021. Yet only two districts are currently in any of the state’s three categories of fiscal distress.

By state law, all districts have to say is that the dollars are needed “to avoid an operating deficit.” At first blush, the clause doesn’t sound problematic until we realize how much leeway it gives districts. For instance, it doesn’t say anything about the size of the deficit they must be facing. Does a $100 shortfall count? Moreover, districts could “game” their budget projections to create deficits on paper that allow them to propose an emergency levy. Or they could choose not to take reasonable cost-containment measures—creating an “emergency” of their own doing—in the hopes of a taxpayer bailout. Yet by using “emergency” language, districts likely increase the odds that voters will approve a tax hike (as opposed to putting a general-operating levy request before voters asking for additional dollars).

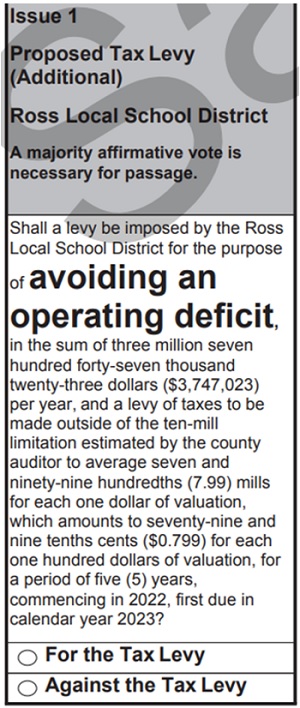

The ballot language for emergency levies is also peculiar. The figure to the right displays Ross’s levy request as presented on voter ballots. What jumps out is the large, boldfaced text “avoiding an operating deficit.” Remember, the ballot language for a normal, general operating or bond levy does not have any bold or large-print font in the question (see here for an example). But state law actually requires the purpose of an emergency levy to be printed in bold and with typeface that is “at least twice the size” of the font around it. As we know from surveys, the wording and presentation of questions can affect the response. What we have here is akin to a loaded question. The language in bold print is likely to lead voters towards a “yes” vote, perhaps out of fear that failing to do so will cause financial ruin for the district (though it could work the other way if people are led into believing a district is mismanaging funds). In the end, the ballot language doesn’t guarantee victory for one side or the other, but it could tip the scales in close races.

In my view, Ohio should eliminate emergency levies altogether. Current emergency levies could be grandfathered or extended, but districts would no longer be able to propose a new one. If districts believe they need more funding, they can always put forward a normal operating tax request before voters without the brazen “emergency” terminology and the outrageous ballot language. Absent elimination, legislators could at least tighten statutory requirements to allow only districts in state-designated fiscal distress categories to put this type of levy on the ballot. They should also consider removing the provision that calls for the large, bold-faced print. The question should be presented neutrally to voters without pushing them in one direction or the other.

Ohio taxpayers deserve to be treated fairly when their local districts request funding. They should have the opportunity to vote on tax rates at conventional times—spring and fall—when decisions about elected offices and other political matters are being made. Taxpayers should also be presented an evenhanded tax request, not one that uses frightening language. With some changes to current statute, state lawmakers would encourage broader participation and present a more neutral question.

[1] The bill allows for an exception if a district is in state-designated “fiscal emergency.”

The mental health crisis has been a persistent headline over the last few years, as research and anecdotal evidence indicate that pandemic-related disruptions have taken a toll. Much of the focus in the education world has been on students, and rightfully so—kids should always be the focus of education-related discussions. But the mental well-being of teachers is also important, and the pandemic has not spared them.

Even before Covid-19, teachers were struggling. A 2017 survey indicated that 58 percent of teachers reported that their mental health was “not good” for seven or more days in the previous month, a significant increase from the 34 percent who reported the same in 2015. Results from a PDK International poll published in 2019 found that half of the teachers surveyed had considered leaving the profession. Fifty-five percent reported that they would not want their child to become a teacher, and cited insufficient pay and benefits, job stress, and feeling disrespected or undervalued as reasons why.

The pandemic has exacerbated these issues. In the spring of 2020, the New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative surveyed over 400 teachers from forty-five different schools to determine pandemic-related impacts. Of the eighteen Covid-related stressors identified by the survey—issues like being separated from family or friends, the difficulty of transitioning to remote work, increased workloads, and having to teach their own kids—teachers reported experiencing an average of seven stressors. Unsurprisingly, teachers who experienced the most stressors reported worse mental health and struggled to cope and teach. A follow-up survey conducted in June 2021 found that more than a third of teachers met the threshold for a diagnosis of depression or anxiety, and one in five teachers exhibited significant symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder—numbers that exceed those reported by health care workers.

As employers, districts and schools have an ethical obligation to ensure that their staff is working in a healthy, safe, and professional environment. But the responsibility doesn’t stop there, as research shows that teacher stress is linked to poor teacher performance and poor student outcomes. A 2008 study found that perceived teacher burnout had a negative effect on student motivation and learning. And in 2016, researchers found a negative association between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and the class average of students’ grades, standardized test scores, school satisfaction, and perceptions of teacher support. When teachers are burned out, students pay the price.

Teacher burnout is also linked to attrition, and attrition impacts student outcomes, too. A 2013 study in New York City found that students in grade levels with higher teacher turnover score lower in both English language arts and math, and that effects are particularly strong in schools with more low-performing and Black students. A 2020 study of teacher turnover in North Carolina found significant drops in math and reading scores due to middle school teacher turnover. Novice teachers are especially likely to quit, with research showing that more than 44 percent of new teachers in public and private schools leave teaching within five years of entry. Add in the price of turnover—which costs districts more than $2 billion a year—and it’s clear that tackling teacher wellness should be a priority for state leaders.

But what should policymakers do? They could make changes to state law, like eliminating mandatory salary schedules so districts can pay teachers more flexibly or fixing Ohio’s teacher retirement mess, which would make teaching a more attractive and sustainable career. Innovative initiatives like administering annual statewide surveys to gather teacher feedback and attrition data or funding public-awareness campaigns aimed at improving perceptions of teaching would also be worthy investments. But a good chunk of teachers’ daily stressors—things like inadequate support from administration, school culture, or student discipline issues—are school-based issues that either can’t or shouldn’t be governed by state lawmakers. The mental health needs of teachers also vary widely across geographic regions, schools, and grade or subject matter, so a one-size-fits-all approach won’t work.

Instead of a top-down approach, the state could empower districts and schools to craft their own initiatives. Ohio’s leaders could create a statewide competitive grant program that awards funds to schools (or to partnerships between schools and community-based organizations) seeking to implement programs aimed at improving teacher well-being. All public schools would be eligible to apply. And like other recently enacted grant programs, there should be a rigorous application process. To ensure teacher buy-in, the state could require applicants to conduct a needs-based assessment that gathers feedback from a representative sample of staff, and then explain how that feedback was used to craft their proposal. Applicants should also be required to develop a monitoring system that gauges the effectiveness of the program and how it might be sustained after the grant.

Although schools should have plenty of flexibility to come up with innovative solutions, the state’s request for applications should offer some suggestions that leaders could adopt or adapt to fit their needs. Fortunately, the feds have already done some of the legwork. 2021 federal guidance regarding school re-openings after Covid disruptions includes a section on supporting educator and staff well-being, and it suggests the following ideas:

These aren’t the only ideas worth pursuing, of course. Feedback from teachers could uncover plenty of other possibilities, as different schools will find value in different strategies. For example, a school where a significant percentage of the student body is comprised of English language learners could invest in robust and individualized professional development that equips staff to better serve those students and, in the process, reduce stress. Schools with extended day and year calendars could decrease the chances of burnout by building planning periods and days directly into the school schedule (and make sure to honor that time). Schools that employ a significant number of novice educators could go all-in on a rigorous mentorship program that offers far more or better support than what’s already required under state law. Those with considerable frustration about student misbehavior could rethink discipline structures or invest in evidence-based and individualized professional development. The possibilities are endless, but the common underlying thread is meeting the expressed needs of teachers so that teachers can meet the needs of students.

For many districts and schools, investing time, energy, and resources into teacher wellness will require traversing new ground. Most administrators and policymakers pay lip service to the importance of teacher well-being, but they rarely follow through with action. Now is the time to change that. If we want the best and brightest students to become teachers, and if we want to hang on to the excellent educators we already have, we need to make teaching an attractive and sustainable career—and that means tackling teacher wellness.

Registered apprenticeship programs offer workers paid, on-the-job learning experience under the supervision of an experienced mentor, job-related classroom training, and the chance to earn a portable industry-recognized credential. When done well, they benefit employers, employees, and the economy—the definition of a win-win-win. It should come as no surprise that they’ve seen a surge of bipartisan support and interest from policymakers who are grappling with the pandemic’s impact on the workforce.

But apprenticeships aren’t just for adults. Youth apprenticeships have been hailed as a crucial strategy for establishing affordable and reliable pathways from high school into college and the workforce. Like registered apprenticeships, high-quality youth apprenticeship programs offer students the chance to learn and earn under the tutelage of experienced professionals, are tied to career-based instruction, and culminate in industry-recognized credentials or postsecondary credit. But unlike registered apprenticeships, they are far less prevalent and often out of reach for most students.

In an effort to address this issue, New America launched the Partnership to Advance Youth Apprenticeship (PAYA) in 2018. PAYA is a multiyear collaborative designed to improve awareness and help cities and states expand access to high-quality apprenticeship opportunities for high schoolers. PAYA’s latest contribution to the field is a state policy playbook for youth apprenticeships published by the National Governors Association. Though the playbook would be a useful tool for any state leader, the recommendations focus primarily on governors, as they are in a unique position to influence state policy environments and be a unifying force across sectors.

Using this playbook as a guide, here’s a look at three steps that Ohio Governor Mike DeWine could take to tap into the potential of youth apprenticeships.

1. Establish a statewide vision

Ohio has a solid apprenticeship structure for adults that includes state laws regarding governance, an ApprenticeOhio site that offers the public a host of information, and an Ohio Means Jobs site where job seekers can search through over 1,300 apprenticeship opportunities available in the Buckeye State. When it comes to youth apprenticeship programs, though, information is a lot harder to come by. ApprenticeOhio references pre-apprenticeships, but there doesn’t appear to be an easily accessible or searchable list of programs designed specifically for high school students. Information regarding industry-recognized credentials abounds, but there are no clear links between state-approved credentials and youth apprenticeship programs.

One reason why there’s a lack of information and opportunities is that youth apprenticeships just aren’t a priority. Consider Ohio’s Attainment Goal 2025 as a comparison point. Because attainment is a priority for state and local leaders, a ton of new programs and initiatives have cropped up over the last several years. Apprenticeship—at least at the youth level—hasn’t benefited from the same priority level status, which means attention, funding, and manpower are going elsewhere.

Establishing a statewide vision for youth apprenticeships would go a long way toward changing that. The governor could lead the charge by calling together a group of key stakeholders from various sectors—leaders in secondary and higher education, industry, policy, and community outreach and advocacy—to discuss how youth apprenticeship programs could help solve some of Ohio’s most pressing issues. The PAYA playbook notes that “a strong, measurable, time-based vision” is necessary to provide employers, students, and schools with the “reassurance and guidance” they need to invest in youth apprenticeships. With this in mind, the governor could use the feedback gathered in stakeholder meetings to establish measurable and time-based statewide goals for the number of youth apprenticeship programs available, student and employer participation, and outcomes.

2. Increase awareness and improve alignment

Getting state and local leaders invested is only one piece of the puzzle. Another piece is students themselves—if they aren’t aware of the opportunities available to them, the potential of youth apprenticeships will remain untapped. The playbook recommends tackling student awareness head on by weaving career exploration and preparation throughout K–12 education. Specifically, the playbook calls on governors to create a continuum of career readiness for students that would start in the early grades with exploration, and then expand to preparation and training as students get older. Doing so would not only ensure that students are aware of various career opportunities, it would also give K–12, postsecondary, and industry leaders an opportunity to ensure alignment across sectors.

There are already some laws on the books regarding career awareness for K–12 students, but Ohio can do better. To make it work, state leaders would need to provide consistent funding for career exploration and training programs, as well as career guidance and counseling, all of which are integral to making the continuum effective. For examples on how other states have made this work, the playbook points to Nebraska, which has a Workplace Experiences Continuum as well as Career Readiness Standards, and Hawai’i, which developed a work-based learning continuum in collaboration with employers.

3. Encourage employer participation

The final—and perhaps most crucial—piece of the puzzle is employers. If Ohio employers aren’t willing or able to participate in youth apprenticeship programs, then a statewide vision and student awareness won’t matter. To encourage employer participation, the playbook recommends that governors focus on reducing regulatory, financial, and logistical barriers. Ohio has already taken care of some regulatory red tape, as state law allows minors who are employed as part of “work-oriented programs with the purpose of educating students” to work more than forty hours in one week including during school hours. Ohio is also headed in the right direction with financial incentives, as the recently passed Senate Bill 166 offers tax credits to businesses that provide work-based learning experiences for students enrolled in approved CTE pathways.

But to truly capitalize on the potential of youth apprenticeships, state leaders should invest in apprenticeship-specific incentives. For example, employers in Georgia who participate in work-based learning programs through the Georgia Department of Education can receive up to a 5 percent reduction in their premium for workers’ compensation insurance. And in Rhode Island, the Governor’s Workforce Board oversees a Work Immersion program that helps employers train prospective workers through paid internships by reimbursing them at a rate of 50 or 75 percent for wages paid to eligible participants. Ohio could offer similar programs but tailor them toward employers who participate in youth apprenticeships.

***

Dealing with the economic fallout of the pandemic, worker shortages, and skill and readiness gaps isn’t likely to get any easier over the next several years. Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet that can solve all those problems. But work-based learning programs like apprenticeships could help immensely, and youth apprenticeships, in particular, could be a boon for young people preparing to enter the workforce. Here’s hoping the governor and other lawmakers also see their potential.

Efforts to diversify the pipeline of students, graduates, and workers in in-demand STEM fields often start in middle and high schools. Data indicate some promising momentum there, but higher education can also be part of the solution. A recent working paper looks at the wide-ranging impact of one university’s work to bring promising students across the gap from high school to college.

An anonymous “elite technical university in the Northeast”—dubbed Host Institution (HI)—annually runs a number of summer STEM programs for rising high school seniors from across the country. The analysts used applicant data from 2014 to 2016 for three of these programs to study whether participation in them increased students’ likelihood of attending college and completing a degree in a STEM field.

All applicants were highly motivated (the application materials were voluminous and the process lengthy and detailed) and high achieving (submissions included course grades and test scores), so this is not a typical population. The most-intensive program is also pricey, although HI paid for everything but student transportation. The university’s goal was to induce promising candidates—specifically, young people who might fail to matriculate due to non-academic considerations—to make the leap to college and to choose HI. More than 2,000 students applied to the summer programs each year, far more than could be accommodated. Officials gave priority to eligible applicants who would be the first in their family to attend college, who hailed from families without science and engineering backgrounds, who attended high schools that historically sent less than 50 percent of their graduates to four-year colleges, who attended high schools that “presented challenges for success” at elite universities (rural, low-income, etc.), or who were members of a group underrepresented in STEM (Black, Hispanic, or Native American). Priority was also given to students from certain regions of the country typically underrepresented at HI. Gender balance in each program was imposed, as well.

All this effort produced a group of 600 to 750 underrepresented students in each of the three years, still more than the slots available. The top-ranked students were guaranteed a slot but randomly assigned to either a six-week on-campus residential experience, a one-week residential camp, or a six-month online program concluding with a single-day campus visit in the summer. The lower-ranking students were randomly assigned to either the remaining slots in the online program or to the control group (i.e., those not receiving a slot). Both treatment and control students were observed for five years following the summer session.

In terms of college enrollment, almost all applicants enrolled in a four-year college within one year of high school graduation. That includes 87 percent of the control group—those who were not offered a slot in HI’s summer programs—likely reflecting the high-achieving, highly-motivated nature of the students applying. The treatment group upped that percentage by approximately 3 points. While 8 percent of the control group ultimately enrolled in HI, attendance in any of the three summer programs increased that percentage—an additional 17 percentage points for the six-week program, 5 points for the one-week program, and 4 points for the online program. The summer programs also induced a shift in enrollment toward higher quality colleges. Enrollment at any of Barron’s most competitive institutions (including HI) was boosted by a statistically significant gain of 17 percentage points for those offered a slot in the six-week program, by 14 points for the one-week program, and by 10 points for the online program.

As for degree completion, 53 percent of control group students graduated from college within four years of high school graduation, 8 percentage points higher than the national average in that period but lower than might have been expected for such a motivated population. Meanwhile, between 56 and 61 percent of students offered summer program slots all those years earlier did the same. The highest completion rates were for those offered slots in the two residential programs, mainly driven by graduates from HI. Around 80 percent of the degrees earned within four years by the treatment group were in STEM fields, more than 12 percentage points higher than in the control group, with most of the increase driven by degrees earned from HI itself.

While the pre-program motivation of students in the study cannot be discounted, the analysts conclude that being offered a spot in the university’s summer programs boosted the college-related human capital of these high school students, most of whom came from families and/or schools with little such capital of their own. This made it easier for them not only to apply to HI, but also to similarly competitive institutions and to complete STEM degrees. The structure of the six-week summer program especially—designed to mimic a compressed freshman year at HI—was seen as important to turn motivation into access and academic success. There is a brief discussion of costs at the end, noting that HI pays all expenses except for transportation to and from the university, which range from a hefty $15,000 per student in the six-week program to less than $2,000 per student for the online program. The analysts stop short of a full-blown cost-benefit analysis, however, leaving that to future research. The results are promising, but scalability and generalizability are still hard questions that need answers.

SOURCE: Sarah R. Cohodes, Helen Ho, and Silvia C. Robles, “STEM Summer Programs for Underrepresented Youth Increase STEM Degrees,” NBER Working Papers (July 2022).

Just over a decade ago, the Brookings Institution published Terry Moe’s eye-opening book on teachers unions. His study revealed how local unions shape public education through the process of electing school board members. If their electioneering efforts were successful—and without much organized opposition, they often were—unions could then negotiate labor-friendly contracts with school boards beholden to their interests.

Since Moe’s groundbreaking work, little to no analysis has been undertaken to continue tracking union influence at the ballot box, even as the policy environment has shifted. The U.S. Supreme Court’s Janus v. AFSCME ruling in 2018, for instance, ended the automatic collection of “agency fees” for teachers who opt out of unions, perhaps weakening their influence in local politics. On the other hand, as the debates over school closures during the pandemic remind us, unions still clearly wield power in local decision-making.

A new study by Michael Hartney of Boston College offers new evidence about teachers union influence in school board elections. The analysis looks at results from 2,345 competitive races in California held between 1995 and 2020 and 361 races in Florida between 2010 and 2020. Union endorsements are difficult to track systematically, but he collects information from various sources to determine support (e.g., political action committee reports and media accounts). In some cases—mainly elections in small districts—he was unable to locate endorsements. That being said, the districts included in the analysis enroll the vast majority of students in each state (about 90 percent).

Analyses show that a large majority of union-backed school board candidates win. In California, union-endorsed candidates won 71 percent of their contests, while in Florida 63 percent won. As might be expected, union-backed incumbents prevailed even more frequently, winning a whopping 90 percent of their races in California and 80 percent in Florida during the period of study. In terms of trends, candidates with union support have consistently fared well in school board races over time with no substantial changes in their winning percentages. Perhaps more surprising, given unions’ traditional alignment with Democrats, union-backed candidates perform just as well in districts with more registered Republican voters.

While indicative of unions’ continuing power to elect board members, these basic data don’t necessarily capture the effect of a union endorsement per se on a candidate’s likelihood of being elected. As Hartney acknowledges, candidates might receive support because of qualities that would have led to victory even without an endorsement. In other words, there may be some “selection bias” at work, thus overstating the true importance of union endorsements. To pinpoint impacts, he conducts statistical analyses that control for incumbency and the competitiveness of an election, along with candidate’s occupation and demographic background. Results indicate that endorsement does indeed increase the likelihood of winning—having impacts roughly similar to incumbency, a well-known political advantage. Further confirming the effects of an endorsement, Hartney shows that among a small subset of candidates who ran at least one race with and without an endorsement, the union backing significantly boosted their chances of being elected.

School reformers have made many attempts to organize groups that counterbalance union influence at the ballot box. But despite the valiant efforts, the unions are rarely knocked off their perch. As Hartney writes, “Across time and space, irrespective of the political or geographic environment, union-backed candidates are much more likely to win than their unendorsed counterparts on Election Day.” Perhaps the winds will shift with the rise of parent-driven advocacy and frustration with teachers unions’ role in recent education debacles. But if history (and political science) is our guide, they’ll remain highly active in school board elections—it’s in their self-interest to be—and get their way more times than not. With political clout like this, it’s no wonder why adult interests dominate our public schools.

Source: Michael T. Hartney, “Teachers’ Unions and School Board Elections: A Reassessment,” Interest Groups and Advocacy (2022).

A few years ago, in the midst of debates over academic distress commissions (ADCs), Governor DeWine said “The state has a moral obligation to help intervene on behalf of students stuck in failing schools.” That was true then, and is still true today. Yet Ohio policymakers have wrestled with what policies can best drive improvement. For many years, Ohio has focused on turning around entire school districts, the idea behind the controversial ADCs.

Another approach—required under the federal law known as ESSA—is to focus on improving individual schools. But this effort has gotten significantly less attention. What is Ohio doing to implement ESSA’s school improvement requirements? How does the state identify low performers and what steps are taken after identification? Which schools are currently in improvement status? What can the state do to strengthen policy in this area?

The Fordham Institute invites you to an online event to discuss school turnaround policy in the Buckeye State. Dr. Beth Schueler of the University of Virginia will present data from her national study on school improvement. Aaron Churchill of the Fordham Institute, will present his findings from a new analysis of Ohio’s school improvement policies. An audience Q&A will follow the presentations.

August 30, 2022

10:00–11:00am ET

Online via Zoom