To address teacher shortages, Ohio needs better data

Over the last few years, dozens of Ohio school districts have expressed growing concern

Over the last few years, dozens of Ohio school districts have expressed growing concern

Over the last few years, dozens of Ohio school districts have expressed growing concern over teacher shortages. The start of the most recent school year was no exception, which is perhaps why the Ohio Departments of Education and Higher Education sponsored regional meetings aimed at gathering ideas for how to improve teacher recruitment and retention efforts.

It’s important to remember that teacher shortages have been making headlines for years. According to research by the Center for American Progress, enrollment in teacher-preparation programs nationally fell by more than one-third from 2010 to 2018, with Ohio posting a decline of nearly 50 percent. Ohio was one of nine states where the drop totaled more than 10,000 prospective teachers. State data also indicate that, as is the case with public school enrollment, the number of public school teachers has mostly declined over the last decade; Ohio reported having 99,682 teachers in 2020, compared to approximately 111,172 in 2010.

To make matters even more complicated, teacher shortages vary from place to place. A recent paper published by Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform uses teacher vacancy data from Tennessee to create a framework for “understanding and predicting” teacher shortages in states, regions, districts, and schools. The findings indicate that staffing issues are “highly localized,” which makes it possible for teacher shortages and surpluses to exist simultaneously—and explains why some districts and schools are struggling to staff classrooms while others aren’t.

For Ohio, pinpointing where shortages exist is crucial. Detailed data on staffing shortages (and surpluses where they exist) would help policymakers craft short- and long-term strategies to bolster the teacher pipeline, allow researchers to track changes over time, and aid teacher preparation programs in identifying where they should beef up recruitment efforts. If Ohio leaders don’t know where shortages are the most significant and how they have (or haven’t) changed over time, it’s much more difficult to create effective policy solutions.

Unfortunately, statewide data on teacher vacancies don’t exist in a single, easily accessible place. Districts track vacancies so they know which positions to fill, but they aren’t required to report those data to the state. They also aren’t required to track or report attrition or retention data, or gather feedback on why teachers choose to leave or stay. That means if there are significant numbers of teachers across Ohio leaving the profession, we don’t know why. We can make reasonable guesses. Research indicates that working conditions have a strong influence on teachers’ employment decisions, and it’s no secret that better pay would go a long way toward keeping educators in classrooms. But we just don’t know for sure. And while federal data can shed some additional light on school staffing issues, the information is not detailed enough to point Ohio toward state-specific strengths and weaknesses.

To truly tackle teacher shortage issues in the Buckeye State, we need more and better data. A good place to start would be taking a page out of North Carolina’s book and compiling an annual report about the state of the teaching profession. Such a report could include data on teacher vacancies, attrition, and mobility, all of which could be disaggregated by region, district, grade level, and subject area. We could even look at shortages by teacher experience level and teacher demographics. Collecting these data and publishing them annually would give state leaders the ability to track trends over time, and would help pinpoint potential problem areas to head-off future teacher shortages. It could also provide additional insight into the state’s efforts to diversify the profession, which should be a critical priority going forward.

To get the pulse of the current situation, though, state leaders should consider commissioning a statewide retention survey. This survey would give Ohio teachers who leave the profession an opportunity to express their thoughts on a wide variety of issues that impact satisfaction and, in turn, retention. Such issues could include salary, health and retirement benefits, day-to-day working conditions (things like school culture, student discipline, and support from administrators), and the quality and quantity of professional development opportunities. Like the annual data publication proposed above, these survey results could be organized into a report that’s publicly available and easily accessible. State leaders could even hire a third-party organization that specializes in teacher policy to analyze the results and identify a handful of recommendations that districts and the state could immediately implement in an effort to improve retention.

The bottom line is that, if Ohio wants to tackle its teacher shortages, state and local leaders need to understand the breadth and depth of the problem. They can’t do that without easily comparable data from all public schools and feedback from the field, so obtaining those data should be a top priority for lawmakers during the upcoming budget season.

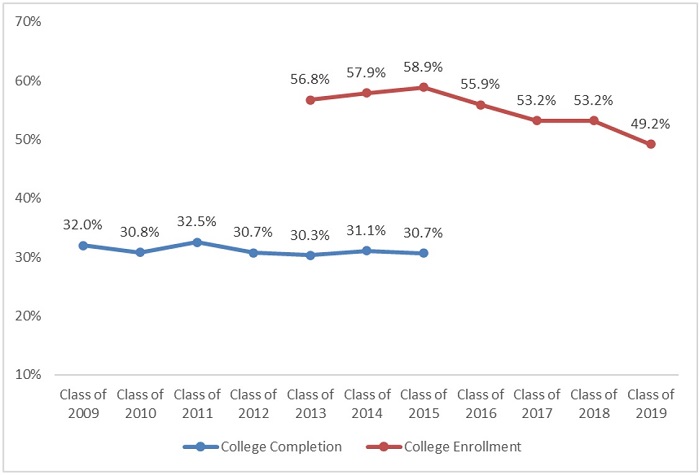

In November, the Ohio Department of Education released the latest college enrollment and college completion rates of Ohio’s high school graduates. Though following national trends, the data are eye-opening, as enrollment rates slumped below 50 percent for the first time since the department started reporting these numbers. Meanwhile, completion rates clocked in at a dismal 31 percent.

The figure below displays data on all the graduating classes for which the department has released data. The lag in reporting is due to the two- and six-year “lookbacks” (discussed in turn) for the college enrollment and completion rates, respectively.

Figure 1: College enrollment and completion rates for Ohio’s classes of 2009–19

These raw data could be interpreted myriad ways, but here are my thoughts on these trends:

Most of all, the college enrollment and completion data remind us that higher education isn’t the only pathway that Ohio’s young people tread as they enter adulthood. Indeed, it’s no longer the pathway that even a majority of students choose after high school. While these trends could certainly reverse, retooling K–12 education to better balance the needs of college- and career-headed students is long past due.

Try saying it with us: “Choice and competition are good.” Don’t take our word alone. On the left, President Joe Biden said:

The heart of American capitalism is a simple idea: open and fair competition—that means that if your companies want to win your business, they have to go out and they have to up their game. . . . Fair competition is why capitalism has been the world’s greatest force for prosperity and growth.

And on the right, President George W. Bush stated:

Free market capitalism is the engine of social mobility—the highway to the American Dream. . . . If you seek economic growth, if you seek opportunity, if you seek social justice and human dignity, the free market system is the way to go.

Their remarks, of course, refer to economic systems writ large, while the report that follows is about primary and secondary education. Even so, in the world of K–12 education, choice and competition are also the way to go. Choice empowers families to select the schools that best fit the needs of their kids, be they district options or alternatives such as public charter schools or private schools. No longer are parents shackled to a singular, residentially assigned, district-operated school that may or may not educate their children to their full potential.

Competition—the other side of the same coin—encourages schools to pay closer attention to the needs of parents and students who, if dissatisfied, can vote with their feet and head for the exits. This sort of “market discipline” helps to promote productive habits and effective practices across both the public and private school sectors.

National polling shows that strong majorities of Americans agree with the intuition behind expanded school choice. Rigorous analyses also reveal benefits to students when states foster choice-friendly environments. Studies on the “competitive effects” of choice programs (both public charter and private school voucher) in states such as Arizona, Florida, and Louisiana have uncovered academic gains for students who stay in traditional public schools. A sweeping national study from our Fordham Institute colleagues in Washington, D.C., found that district and charter students make stronger academic progress when they live in metro areas with more options.

Closer to home, we published a 2016 study by Drs. David Figlio and Krzysztof Karbownik finding that Ohio’s private school voucher program, known as EdChoice, lifted achievement in district schools during its very first years (2006–07 to 2008–09).

So what brings us here again?

In short, the detractors haven’t gone away, the self-interest of the “education establishment” remains strong, and accusations continue to fly that choice programs harm traditional public schools. Here in Ohio, the latest incarnation is the “Vouchers Hurt Ohio” coalition, a group of lobbyists, district administrators, and school boards that have sued the state in an effort to eliminate EdChoice, the state’s largest voucher program, which now serves some 60,000 students. Presently pending before a Franklin County judge, their lawsuit claims that EdChoice hurts district finances and results in more segregated public schools. Though not expressly stated, their claims imply that district students themselves may also be harmed academically.

The plaintiffs build their case around basic school funding and demographic statistics. Their numbers, however, cannot prove cause and effect. For instance, as evidence of segregation, they cite data from the Lima School District, which enrolled 54 percent students of color pre-EdChoice, a number that has since risen to 65 percent. Their implication is that EdChoice is responsible, but they ignore even the possibility that this trend could reflect larger demographic shifts that are entirely unrelated to vouchers (e.g., White families exiting the district and/or minority families moving in). Unless one conducts rigorous analyses that separate the impacts of EdChoice from other factors, superficial statistics are apt to mislead.

To conduct a more careful investigation of the impacts of EdChoice, we turned to Stéphane Lavertu of The Ohio State University. He is a fine scholar, with a strong track record of evaluating various school choice and accountability initiatives in the Buckeye State. His work includes a widely cited national evaluation of charter school performance for the RAND Corporation, along with numerous studies on local school governance and policy that have appeared in peer-reviewed academic outlets such as the Journal of Public Economics, American Political Science Review, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, and Journal of Policy Analysis and Management.

The truth of the matter turns out to be far different than the critics’ claims. In studying the state’s performance-based EdChoice program[1] from inception to the year just prior to the pandemic (2006–07 to 2018–19), Dr. Lavertu uncovers the following:

The available data did not allow Dr. Lavertu to draw clear conclusions about the causal impact of income-based EdChoice, which bases voucher eligibility on family income.[2] That being said, the evidence—circumstantial as it may be—indicates that this newer program (launched in 2013–14) has no adverse impact on districts.

“The sky is falling,” cry the Chicken Little critics of Ohio’s choice programs. But they are mistaken. District students are not left as “collateral damage” when parents have more education options and decide to pursue them. Quite the contrary: the increased competition seems to stir traditional public schools to undertake actions that benefit district students. For judges, journalists, and Ohioans everywhere, we say this: don’t believe the critics’ hype. And for Ohio policymakers, we say: keep working to expand quality educational choices. Free and open competition is known to fuel economic growth. In the same way, it can also drive excellence, innovation, and greater productivity in our public and private schools.

NOTE: This piece is the foreword to our recent report The Ohio EdChoice Program’s impact on school district enrollments, finances, and academics by Stéphane Lavertu and John J. Gregg. The full report can be read or downloaded here.

[1] Eligibility for performance-based EdChoice hinges on the academic performance of the district school to which a student is assigned. In 2021–22, 36,824 students participated in this program.

[2] In 2021–22, 20,783 students participated in this program.

Open enrollment—when students are allowed to enroll in district schools other than the one to which they would be assigned based on their residence—is one of the oldest school choice options in the country. It is also widely available (forty-three states have some form of it) and utilized heavily by parents looking for alternatives to their zoned district school. However, program rules and operations can differ widely from state to state, including features that inhibit use or favor systems over families. A new report from the Reason Foundation analyzes the various versions of open enrollment and ranks them based on observed best practices in state policy.

First up, analyst Jude Schwalbach spells out the difference between intradistrict open enrollment—where students can choose other schools within their district of residence—and interdistrict open enrollment—where students are allowed to attend schools in a different district than the one in which they reside. Both are considered best practices, but only if districts are required by the state to offer such options (on a space-available basis) rather than given the option to do so. Additional identified best practices include transparent state- and district-level reporting of seat availability and open enrollment utilization; simple and readily-available information for parents on how, when, and where to apply; and zero tuition or fee charges for application and participation. (Interestingly, transportation is not on the radar here, even though the Reason Foundation has touted its importance to school choice previously.)

Unsurprisingly, no state hits all of these best practices, but several are close. Arizona, Florida, and Utah top the list, lacking only the state-level reporting requirements. Also among the high-flyers are Kansas and Oklahoma, which meet all of Reason’s best practices save for requiring intradistrict open enrollment. The list drops off quickly from there. The most-common best practice among states is zero tuition for family participation, in force in twenty-four states.

Twenty-three states hit none of the best practices, which is troubling, but that’s not to say that they don’t offer some form of open enrollment. One such state was Fordham’s home state of Ohio. Here, more than 83,000 students utilized the interdistrict variety in 2021, even though the state does not mandate it and participation is driven more by districts’ own financial interests than a state requirement. Intradistrict open enrollment is similarly voluntary and spotty, which leads Ohio to a zero on the best practices chart. We have seen again and again the inequitable outcomes which result from giving districts discretion to open their borders voluntarily. Thus, Ohio’s zero here is warranted. Nevertheless, it is telling that, even without concise information, easy access, or specific prohibition of tuition charges, thousands of Ohio families have sought out open enrollment each year. Were Ohio to adopt Reason’s best practices, even more doors would open to families and students looking for a public school option that meets their needs.

Schwalbach closes the report by providing a checklist for each state of the steps required to boost their best practices score to 100 percent. Here’s hoping more states will take advantage of open enrollment to help families access more and better educational options.

SOURCE: Jude Schwalbach, “Public schools without boundaries: Ranking every state’s K-12 open enrollment policies,” Reason Foundation (November 2022).

Authorized by Congress in 2004, the Washington, D.C., Opportunity Scholarship Program (OSP) is one of the longest-standing voucher programs in the nation. It is also the only federally-funded one. While its fortunes have changed as congressional and executive branch leadership has switched parties over the years, the program has endured. As a result of its longevity, OSP is a perfect lens through which to study the long-term effects of voucher usage. New research in the AERA Journal looks at the impact of the program on participants’ college enrollment rates.

Researchers Matthew Chingos and Brian Kisida go back to the first two OSP application rounds in 2004 and 2005 and identify 1,776 students who entered the voucher lottery—they applied for seats in oversubscribed grade levels—and who can also be observed in OSP administrative records for at least two years after their expected high school graduation. National Student Clearinghouse data provide college enrollment information.

The treatment group comprised 1,059 students who won the lottery and were offered an OSP voucher; lottery non-winners were assigned to the control group. OSP applicants overall had an average family income of about $18,000 in 2004–05, and less than 20 percent came from married, two-parent families. Almost all were Black or Hispanic, and almost a quarter were already utilizing school choice by attending a charter school at the time of application. Treatment group students were slightly more likely than control group students to be Black or Hispanic and had slightly lower family income. Chingos and Kisida run an intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis, noting that only 74 percent of those offered a voucher actually used one and some students in the control group accessed private schools without the aid of OSP. Of those who accepted the offered voucher, approximately 30 percent utilized it for four or more years.

The college enrollment rates for the treatment and control groups were the same, statistically speaking, though voucher recipients were slightly less likely to enroll within three years of graduation, but slightly more likely to enroll four and five years after graduation. Chingos and Kisida theorize that these patterns could be caused by delays in graduation for voucher students needing extra time to complete diploma requirements (which could include higher requirements for private school students than for their public school peers) and observed improvements in the overall educational outcomes in D.C. district and charter schools after 2004.

Unfortunately, the data do not yet reach far enough to look at college completion outcomes for OSP students, an important point where outcomes for the two groups might diverge significantly. That is a study for another day.

SOURCE: Matthew M. Chingos and Brian Kisida, “School Vouchers and College Enrollment: Experimental Evidence From Washington, DC,” AERA Journal (November 2022).

First launched in fall 2007, Ohio’s EdChoice voucher program served more than 55,000 students in 2021-22. The program offers state-funded scholarships to eligible students and allows them to attend a private school. Critics have alleged that EdChoice negatively impacts traditional school districts, and a coalition of districts has sued the state on such grounds. But how true are the claims? Does EdChoice actually cause fiscal distress or decreased academic performance?

In partnership with School Choice Ohio, we invite you to join us on December 14th to hear results from a forthcoming Fordham Institute report by Stéphane Lavertu, a professor at The Ohio State University. Based on in-depth analyses of district enrollments, finances, and performance, Dr. Lavertu will present his empirical findings about the impacts of EdChoice on traditional public schools. This event is in-person, and an audience Q&A will follow the presentation.

December 14, 2022

9:00-10:00 am

Columbus Athletic Club

Full video is here: