All schools, no exceptions, need a learning plan for this fall

With fall right around the corner, the discussion in Columbus has turned from the spring closures to what school will look like come September.

With fall right around the corner, the discussion in Columbus has turned from the spring closures to what school will look like come September.

With fall right around the corner, the discussion in Columbus has turned from the spring closures to what school will look like come September. Last week, Governor DeWine said that he thinks schools will be open this fall, a Senate committee heard from education groups about reopening, and the Ohio Department of Education released draft guidance for restarting schools. Of course, no one can be sure at this point what the fall will hold. But one thing’s for certain: Schools need to be ready to hit the ground running.

Because of continuing health uncertainties, most analysts agree that schools must have plans for remote learning in the coming year. These “continuity of education” plans would address how teaching and learning happens if children do not physically attend schools, whether by health order or by student and parent choice. To reduce safety risks in facilities—e.g., practicing social distancing—schools also need to be ready to educate students via hybrid learning models in which time is split between traditional classrooms and home.

While learning plans themselves can’t guarantee results—execution is vital, too—the past few months have taught us that having a plan is absolutely essential to being prepared in the midst of uncertainty. Understandably, most schools lacked plans this spring to turn on a dime and transition to distance learning. But this ill-preparedness surely explains the jumbled response across many schools. In Cincinnati, for instance, the district struggled to make contact with thousands of students, much less engage them in rigorous academic work. Several districts—Lakewood, Elida, Revere, and Solon—threw in the towel on remote learning and cut their school years short. Various news reports have spotlighted schools that have all but given up on grading student work during the building closures.

Of course, much like the pandemic itself, these problems haven’t been confined to Ohio. The Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE), a national organization, reported in May that one-third of the districts they’ve been tracking still “do not set consistent expectations for teachers to provide meaningful remote instruction.” Deeply troubling also is that it identified a few districts that don’t even require their teachers to give feedback on student assignments. A national survey from Education Week earlier this month likewise paints a bleak picture: Almost a quarter of students are MIA, pupil engagement has fallen, and teachers are working fewer hours.

Again, what happened this spring is pardonable given the unforeseen circumstances. But getting caught flat-footed can’t happen again. Experts are already predicting substantial learning losses due to the out-of-school time. Tragically, Ohio’s neediest students—low-income, special education, English learning learners among them—have likely suffered the most damage.

To tackle these immense educational challenges, all Ohio schools, without exception, need a game plan for the fall. One certainly hopes that schools are already busy crafting these plans with the input of parents and students, community groups, health officials, and education experts. But it would be naïve to assume that each and every school is undertaking such robust preparations.

State policymakers, therefore, have a responsibility to act and ensure that all schools are ready and able to provide instruction this fall. Governor DeWine should ask every school district and charter school to submit “continuity of education” plans that should be made publicly available. Pennsylvania required its schools—this spring!—to create plans that include descriptions of expectations for teachers and students, grading and attendance practices, access to devices, and supports for special education students during the prolonged closure. Importantly, these plans are posted on district websites, so that families and communities have a common understanding of what to expect when students are learning at home. Some of the plans are refreshingly concise and reader-friendly. (Check out a few here, here, and here).

By failing to require continuity of education plans earlier this year, Ohio is already behind the eight ball. But it should absolutely follow in Pennsylvania’s footsteps for the coming fall. To be sure, policymakers shouldn’t make this yet another exercise in state bureaucracy. There need not, for example, be an approval process. But these plans would provide much-needed transparency and ensure that every school has given thought to educating students if and when they have to learn remotely.

A replay of this spring would be inexcusable. Districts and schools around the nation and in Ohio are figuring out ways to make remote education work, and leaders have three months to plan for next year. Parents and students are counting on schools to deliver an excellent education this coming fall, no matter what. State policymakers need to ensure that schools are ready to reopen.

Over the last few months, there’s been no shortage of pieces declaring that the novel coronavirus has drastically and permanently changed everything. Education is no exception.

Most of the press coverage on educational impacts has focused on traditional public schools. That’s understandable, as they educate the vast majority of Ohio students. But school choice options like charter and private schools are also feeling the effects of COVID-19. And although it’s too soon to tell just how much lasting change American schools will face thanks to the pandemic, there are some short-term shifts we can predict and analyze.

Here’s a look at how the coronavirus could impact two major issues for Ohio charter schools—funding and enrollment.

Funding

First things first, it’s important to note that Ohio charters have long faced significant funding shortfalls compared to traditional districts. A study published by Fordham last year found that charters in the Big Eight received approximately $4,000 less per pupil than their district counterparts, a whopping 28 percent gap. Districts, meanwhile, claim that they’re the ones who are shortchanged thanks to the state’s “pass-through” funding method. Rather than paying charter schools directly for the students they teach, the state requires funding to go through districts in the form of a deduction to their state aid. This has led traditional districts to claim that charters are “siphoning” money from them, even though the district isn’t educating the students tied to those funds.

Prior to the pandemic, there were increasing calls for the state to transition to directly funding charter schools. This change would have soothed, though perhaps not eliminated, many of the funding tensions between districts and charters. Unfortunately, such a shift will be significantly harder as the state tries to address other pandemic-caused fiscal challenges. School districts are probably still open to a change, but it’s highly unlikely the state will be able to tackle an intricate school funding issue in the midst of the current crisis.

Other significant impacts on charter schools caused by COVID-19 are declining state revenues and rising costs. The effect of this financial fallout is two-fold. First and most obviously, charters are facing funding cuts that will hurt their budgets and their capacity to serve kids well. The second impact is more political. The governor’s office recently announced $300 million worth of cuts to traditional K–12 schools. Although charter schools are facing cuts of their own in proportion to their revenue streams and the disadvantaged populations they serve, the media and public school establishment are already suggesting that the charter cuts are not enough. It’s likely that the funding wars will get nastier as both sectors feel the squeeze of tighter budgets—unless Uncle Sam comes to the rescue.

Finally, there’s a possibility that charters may miss out on promised supplemental funding. Last summer, Governor DeWine signed a state budget that included an increase of $30 million per year in state aid for high-performing charter schools. The Ohio Department of Education announced earlier this year that sixty-three schools qualified for the funding. This was a huge win for charter schools. The additional dollars would go a long way toward helping existing charters serve their students well, and would have made it easier to open new schools, expand high-performing networks, and recruit high-performing, out-of-state networks.

That was before COVID-19, though. With an unprecedented budget crisis looming overhead, the state might be tempted to repurpose some of these funds to stem the bleeding in other places. The first round of payments has already been sent to schools, but any plans that were made for the next round of funds could be in jeopardy.

Enrollment

Thanks to months of unexpected homeschooling, thousands of parents have gotten an up-close-and-personal look at what their child’s school is (or isn’t) willing to do to ensure that students are learning no matter the circumstances. If parents don’t like what they’ve seen from their traditional public schools, it’s possible they may start searching for alternative options like charter schools. On the flip side, charter parents who aren’t thrilled with what their schools have done could be gearing up to re-enroll children in their assigned school district. As Douglas Harris notes in a recent piece published by Brookings, any potential enrollment shifts will be determined by one key question: Which schools responded better to the crisis?

The answer to that question isn’t yet clear. Across the country, there are traditional districts and charters that have done a good job transitioning to remote learning, just as there are those that have struggled mightily. Such differences are also on display in Ohio. Overall, it seems like the answer to the “who responded better?” question has less to do with governance structure, and more to do with intangibles like leadership, preparation, and innovation.

Even if charters end up looking attractive to parents, though, Ohio might not see a sudden increase in charter enrollment. That’s because brick-and-mortar charter schools aren’t a viable option in most parts of Ohio. The state currently has 319 charter schools serving just over 100,000 students, compared to 3,063 traditional public schools that serve over 1.5 million children. State law also limits charter schools to opening in a “challenged” school district. As a result, charter schools aren’t a feasible alternative for thousands of Ohio families, even if they wanted to enroll in one.

Virtual charters could step in and fill this void, and it’s possible they may see a jump in enrollment this fall. They are a particularly attractive option for parents who are concerned about potential school closures in 2020–21. If a student is already enrolled in an online school, additional closures and lockdowns wouldn’t disrupt their learning. Virtual schools will also be attractive for parents who are hesitant about the health risks associated with sending their kids back to brick-and-mortar buildings. Enrolling in an online school would keep kids safe at home, while still providing learning opportunities. In either case, what might be the new normal—parents working from home—could lead to an increase in the number of families who opt for virtual charter schools.

It’s also important to remember that charter school enrollment could be impacted by the budget crunch. If schools have to lay off teachers to balance their budgets, or if funding for larger or improved facilities dries up, charter leaders may have to curtail expansion efforts or put a cap on incoming classes. They may have to do that regardless, since recruiting new students is far more difficult in the midst of a pandemic. The magnitude of such impacts will vary from school to school, but it’s safe to assume that the vast majority of financial outlooks will be gloomy.

***

Over the coming months and years, there will be considerable discussion about how the novel coronavirus has impacted traditional public schools. That’s understandable and necessary. The education of millions of students will be affected in serious ways by extended closures, tightening budgets, and potential learning losses. But it’s important to remember that charter schools are also public schools, and that their students and staff also face big impacts. As state and federal leaders continue to debate how to address the fallout of the pandemic, it will be important for them to remember that charters need assistance and support, too.

Editor’s Note: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

In early May, Columbus City Schools released a searing 450-page external audit that took the district to task and called for improvement on many dimensions of governance and performance. Some of the most alarming findings, in my view, concern the failure of the district’s teacher evaluation process.

Last year, only two of the district’s roughly 3,500 teachers were rated as “ineffective” on their official evaluations, and only about 5 percent received the second-lowest “developing” rating, according to district data. But when auditors asked school principals for their honest opinions, more than a third reported that at least 10 percent of the teachers in their schools were ineffective. In some buildings, principals rated nearly 20 percent of their teachers as ineffective. “That’s the highest I’ve ever seen, I was shocked to see that!” the lead auditor told the school board in her presentation of the findings.

There are devastating implications for the thousands of Columbus students assigned to ineffective teachers. Yet the audit findings also raise serious questions about the state’s investment in the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System, the framework used by Columbus in recent years. Unless district leaders learn from the failings of the past system, the audit bodes ill for the revamped evaluation system (dubbed OTES 2.0) that will be rolled out in the coming months. Consider the following three lessons.

Lesson 1: Using locally designed assessments and metrics can lead to inflated performance ratings

Ohio’s teacher evaluation system was first implemented as a response to the Obama administration’s signature Race to the Top competition. The federal initiative was based on two striking findings that were emerging from education policy research at the time. The first showed that, despite the importance of teachers in improving student achievement and substantial variation in their effectiveness, existing evaluation systems failed to differentiate teachers based on their ability to improve student learning. Instead, more than 99 percent were consistently being rated as “satisfactory” regardless of how well their students actually performed. The second finding suggested that a class of statistical models, known as “value-added,” could accurately and reliably identify teachers that were doing the best and worst job of improving student achievement as measured by standardized test scores.

To remain competitive for federal funds, states were required to develop evaluation systems that could differentiate teacher effectiveness and were based, at least in part, on student achievement growth, as measured by value-added models. Since Ohio already had a value-added system in place, it was well positioned to incorporate this information into its new teacher evaluation system.

The original OTES model based half of a teacher’s overall evaluation on student growth. But the problem is that value-added information is available for only a small subset of teachers—those teaching subjects and grades included in annual state tests, which are primarily math and English language arts in grades four through eight. It turns out that 80 percent of Ohio’s teachers don’t receive a value-added designation from the state, and even those who do also teach other subjects that are not covered on state tests. To address these gaps, the state implemented a process for teachers to create their own tests and metrics—called “student learning objectives” (SLOs)—to document their impact on student learning.

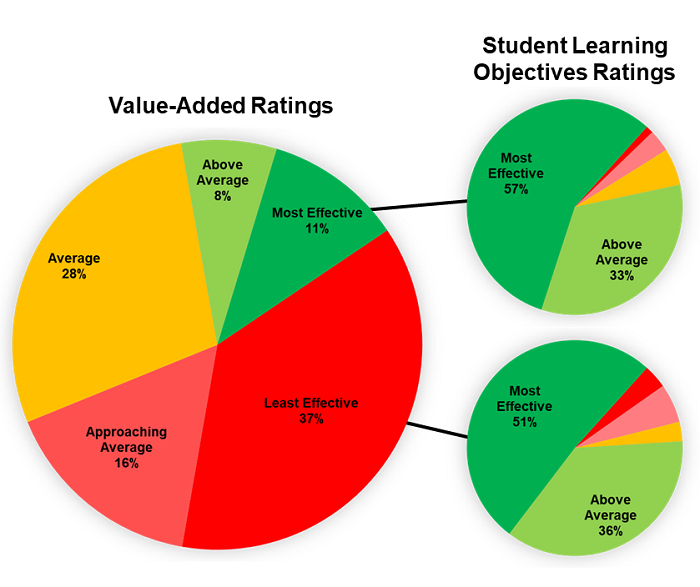

The flaw with SLOs, however, was that individual teachers in effect got to decide how their performance in improving achievement would be measured and evaluated, a system obviously vulnerable to abuse. As the Columbus audit and district data show, teachers have taken full advantage of SLOs to inflate their scores. Consider the roughly 1,000 Columbus teachers who received a state “value-added” designation last year. More than half were rated as below average by the state, and 37 percent received the “least effective” designation based on their ability to raise student achievement on state tests. Because few educators exclusively taught subjects covered by the value-added measure, the vast majority were able to incorporate SLOs into their evaluation calculation. As a result, more than three-quarters of these least-effective teachers were still rated as above-average, and half were rated “most effective,” using teacher-designed SLOs. Indeed, as the Figure 1 reveals, educators whose students demonstrated the least amount of growth on state tests look essentially identical to teachers who improved student achievement the most when we compare them using SLOs.

Figure 1. Comparing value-added and SLO measures of student growth for Columbus teachers (2018–19)

Although the state put in place requirements to ensure that teachers developed valid SLOs, and Columbus appointed committees to review them, it turned out that it is almost impossible to effectively police this process. As one Columbus principal told the auditors, “Teachers could more or less make stuff up for the data part of the teacher evaluations.”

For illustration, consider one Columbus teacher who was rated as “least effective” through value-added, but who received the highest possible student growth rating using SLOs last year. One of her SLOs was based on the book Word Journeys, an impressive framework that divides the development of orthographic knowledge into stages, from “initial and final consonants” to “assimilated prefixes.” The book comes with a screening tool composed of twenty-five spelling words designed to cover each of the stages, and this teacher’s SLO set the goal of increasing the number of words each student spelled correctly between the beginning and end of the year by twelve. Not surprisingly, every student met or exceeded this target.

The problem is that it is impossible to know whether student spelling in this class improved because the teacher did a great job teaching the underlying skills—each of the stages in the Word Journeys framework—or because the teacher simply had students memorize twelve of the twenty-five words she knew made up the book’s screening tool. The former is true learning, while the latter is the very epitome of teaching to the test—a test that teacher herself got to handpick.

Thus, the SLOs were a true Achilles’ heel in the state’s old teacher evaluation system. While OTES 2.0 scraps SLOs, I worry that similar problems will emerge with the alternative growth measures that will replace them.

Lesson 2: Principals need incentives and time to do evaluations right

Under Ohio’s old evaluation framework, student growth—measured either through value-added or SLOs—accounted for only half of each Columbus teacher’s overall evaluation score, and even less in some other districts. The second half came from principal observations. Historically, observations were perfunctory exercises using simple checklists, but to win Race to the Top funds, states had to create much more thorough rubrics. Ohio developed a rubric called “Standards for the Teaching Profession.”

Despite the well-defined criteria on the rubric, Columbus principals appear to have been quite lenient in their evaluations. For example, among Columbus teachers identified as “least effective” by the state through value-added last year, principals rated 90 percent of the educators they observed as “skilled” or “accomplished,” the two highest categories.

Of course, it’s possible that principals were looking at broader aspects of teacher skill and quality not captured by test scores. However, it seems more likely that many principals just didn’t follow the rubric. As one Columbus principal told the auditors, “I don’t use the actual teacher evaluation; it’s very cumbersome. I just fake it.”

I suspect there are two primary reasons many principals failed to embrace the state’s observation protocol. First, the job of a principal in a low-performing, urban district is already overwhelming. From managing student behaviors to taking care of other responsibilities, it seems unrealistic for most principals to find the necessary time in their packed schedules to thoroughly observe and carefully evaluate every teacher with the effort and diligence the process truly requires.

Second, the ability of teachers to inflate their overall ratings using SLOs made the principals’ evaluations pretty toothless. Consider the example I describe above, wherein the teacher’s SLO set the goal of her students spelling twelve words correctly. Not only was the teacher identified as “least effective” by the state based on value-added, she was also rated as “developing” by her principal, the second-lowest possible observation category. Yet, because of her stellar SLO scores, the teacher earned an overall rating of “skilled,” the second-highest available. Knowing that teachers would use SLOs to inflate their final scores, there was little incentive for principals to be critical or honest in their own evaluations since they would not be able to replace the ineffective teachers. Doing so just created unnecessary conflict and awkwardness in their buildings, hardly an outcome that benefited students or made the school better.

Lesson 3: Tie evaluation to teacher support, professional development

Of course, the purpose of evaluations is not simply to identify struggling teachers. It’s also to help them improve when possible, and replace them with someone better if they fail to make progress. Ohio’s Race to the Top grant application assured that “performance data will inform decisions on the design of targeted supports and professional development to advance their knowledge and skills as well as the retention, dismissal, tenure and compensation of teachers and principals.” In practice, none of these appear to have happened in Columbus.

Since SLOs made it almost impossible for teachers to receive the “ineffective” rating, teachers didn’t have to worry about dismissal. More importantly, there is little evidence that the evaluation and observation process helped low-performing teachers improve their craft.

Part of the problem is that principals provided struggling teachers with little useful feedback. As the auditors noted, “the comments recorded on the teacher evaluation instruments by the administrators were generally not constructive.” When examining teacher improvement plans—the actionable product that is supposed to emerge from the evaluation process and guide future instructional improvement—the auditors found “that the goals were written by each teacher, and there was no connection between the comments made by the administrator and the goals and action steps written by the teacher.”

Although former Columbus Superintendent Dan Good sought to achieve better alignment between the district’s professional development spending and its teachers’ actual needs by decentralizing funding and control to individual schools, the auditors found little evidence that the investments were being targeted effectively or producing any measurable returns in terms of better teaching. “The auditors found that professional development in the Columbus City Schools is site-based, uncoordinated, inconsistently aligned to priorities and needs, and rarely, if ever, evaluated based on changed behaviors,” they wrote.

Lessons for OTES 2.0 and Beyond

Is Columbus an outlier? Or is its experience symptomatic of broader problems with the theory of action on which the first iteration of Ohio’s teacher evaluation process was based? The available evidence suggests the latter—and not just in Ohio.

To our state’s credit, Ohio policymakers have recognized many of the issues documented in the Columbus audit, and have attempted to address them in the development of OTES 2.0, which is being rolled out across the state over the coming months. The updated framework eliminates the standalone student growth metric, embedding the assessment of growth with the principal observations instead. It also replaces SLOs with a requirement that district use “high quality student data.” However, I’m pessimistic that the new system will prove to work substantially better than the old one.

First, there is no reason to think that principals will have any more time to complete thorough evaluations or greater incentive to be honest when critical but constructive feedback is deserved than they did under the old model or in the pre-OTES 1.0 days. Second, it seems likely that many district will turn to “district-determined instruments” to assess student learning. As with the SLOs, district officials will likely face considerable pressure from teacher unions to make these assessments easy and highly predictable. If these new assessments rely on relatively shallow question banks, teachers will again be tempted to respond strategically and teach very narrowly to the tests, without realizing broader improvements in student performance. Third, districts like Columbus will surely continue to struggle to deliver sufficiently targeted professional development and other supports that are necessary to address the diverse needs of struggling teachers.

Of course, I hope I’m wrong. Columbus students cannot afford another lost decade.

Vladimir Kogan is an associate professor at the Ohio State University Department of Political Science and (by courtesy) the John Glenn College of Public Affairs. The opinions and recommendations presented in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of the John Glenn College of Public Affairs, the Department of Political Science, or the Ohio State University.

Editor’s Note: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

Author’s Note: The School Performance Institute, of which I am the Director of Improvement, is the learning and improvement arm of United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter-management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus, Ohio. This essay is part of its Learning to Improve blog series, which typically discusses issues related to building the capacity to do improvement science in schools while working on an important problem of practice. However, in the coming weeks, we’ll be sharing how the United Schools Network (USN) is responding to and planning educational services for our students during the COVID-19 pandemic and school closures.

As we are all aware, the COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally altered how our society has functioned over the past few months. The education sector is no exception. As science teachers can attest, one of the unfortunate, enduring realities for life on this planet is that a minuscule virus, just microns in diameter, can leave an outsized impact on life as we know it. Yet a second enduring reality is that the form of life known as Homo sapiens is awfully resilient, and educators across the country are thinking creatively to ensure continuity of education for our students in a remote setting. One of our most pressing challenges is engaging our students and families in remote learning, a fundamentally different system than the brick-and-mortar landscape to which we’re accustomed. Yet that brings us to a core question: How exactly do we define student engagement in the era of remote learning?

Even in “normal” times, student engagement is defined in a wide variety of ways. Does engagement equate to student participation in a class discussion or raising their hand a certain number of times? Does it mean completing a specific lesson component, submitting independent work, or acing the exit ticket? Or is it simply looking in the teacher’s general direction for the duration of class? Clearly, there are a plethora of ways to define engagement, and the challenge of defining it is only exacerbated in a remote-learning setting. For those of us used to having our students within arm’s reach—looking over shoulders at work, reading body language, reviewing written responses, tracking drifting eyes, responding to the positive energy of hands in the air—defining engagement is hard!

Yet defining engagement in the remote learning setting is as important as it is challenging. Imagine that you are a school leader crafting an entirely new system of instructional delivery, and weeks later, you start getting reports of “Last week, we had 87 percent engagement.” Or, “We currently have 63 percent of our students engaged in online instruction.” How would you react? You may look for the low percentages and hold a conference with the applicable grade levels or teachers. Or you may say “great job!” to the teachers or grade levels with high engagement percentages. However, before you begin evaluating the data, you must ensure that engagement is defined consistently. If the teacher with 87 percent engagement simply counts logging onto Google Classroom as engagement, is that really “great” engagement? Similarly, if the teacher with 63 percent engagement counts a student as engaged if they complete the independent practice component of the lesson with clear evidence of thought, is that really so bad? The point is this: Until you establish operational definitions for core components of remote learning, it is impossible to complete thoughtful analysis and reflection.

One way to create these operational definitions is to utilize the wisdom of W. Edwards Deming and his System of Profound Knowledge, which has four components of thought that are highly interdependent: appreciation for a system, knowledge of variation, theory of knowledge, and psychology. Organizations can use this to create a single, unified way of measuring the extent to which students who are learning remotely are engaged in their lessons and work.

The United School Network (and I state this with deep empathy, as, like all schools, we had to get plans together incredibly fast) was defining student engagement differently across its four campuses. Using Deming’s system, and after many discussions, we landed on distinct definitions for and elementary and middle schools.

We may have to modify these definitions as we learn more. But for now, they function as a consistent way of thinking about student engagement across campuses and across our network.

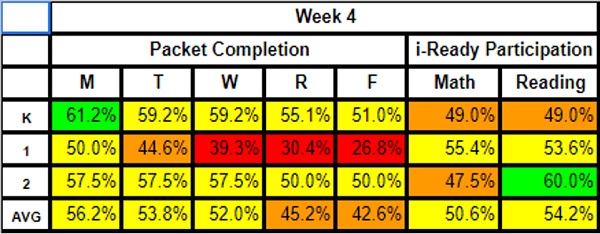

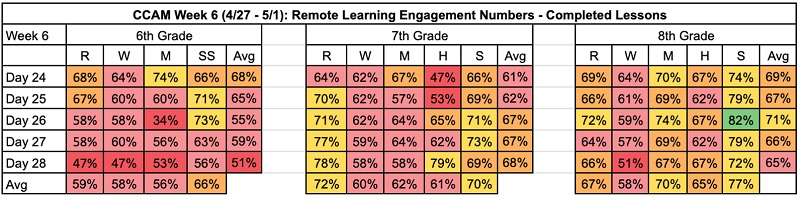

The next step was creating a way to measure engagement, which we did by creating separate trackers for elementary and middle school. This lets us analyze data in an informed way—which is the difference between information (“59 percent engagement. Meaning...what?”) and knowledge (“59 percent engagement, meaning that proportion of my students completed the practice set in its entirety last week.”). The gap between the two is everything when you are establishing a new system like remote learning and trying to improve it. Doing this well means our network leaders, school leaders, and teachers all know exactly how to interpret our student engagement data.

Elementary Example

Middle School Example

This spring is flying by, and soon this unique academic year will be over. However, it appears that a complete return to normalcy next school year is unlikely, so we may find ourselves in the business of remote learning for a while. If that is the case, it is vital for us in the education sector to define core remote learning concepts like student engagement. This will allow our students, families, and teams to have clear expectations, to intelligently analyze our data across grade levels and schools, and to easily see where improvement is necessary. All this will ensure that our most struggling students get the informed support they need.

***

This post has focused on how establishing consistent, unified operational definitions of important concepts like student engagement can help school systems and networks establish effective remote learning systems. It was informed by W. Edwards Deming’s theory of knowledge, which is part of his System of Profound Knowledge. In my next blog post, I will focus on how another component of Deming’s system—the importance of possessing a knowledge of variation—can also help improve remote learning. Stay tuned.

Ben Pacht is the Director of Improvement of the School Performance Institute. The School Performance Institute is the learning and improvement arm of the United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter-management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus, Ohio. Send feedback to [email protected].

Due to plummeting tax revenues, Governor Mike DeWine last week announced plans to slash state spending for the current fiscal year, ending June 30. Among the cost-cutting includes a $355 million hit to K–12 education, a roughly 3 percent reduction in education outlays. With the economy still swooning, legislators are mulling deeper cuts for 2020–21.

Although additional federal aid may soften the financial blow, it’s unlikely to entirely fill the budget holes. School officials still have major belt-tightening in their futures. Since payroll consumes the vast majority of school budgets, reducing personnel expenses is almost inevitable. Districts have various options to this end—e.g., across-the-board salary reductions or freezes to fringe benefits—but layoffs may be necessary too. Indeed, during the Great Recession, many districts addressed fiscal challenges this way, as nearly 300,000 school employees nationwide lost their jobs (about 4 percent of the K–12 workforce).

Unlike businesses, which tend to have broad discretion when downsizing, school districts typically have to follow detailed “reduction in force” procedures set forth in state statute and/or collective bargaining agreements with employee unions. In many states, these policies include a last-in, first-out (LIFO) provision that forces districts to lay off younger teachers, while protecting the jobs of those with more seniority. Education scholars and advocates, however, have flagged three concerns with this practice.

Commendably, several states don’t mandate a last-in, first-out process. Ohio, however, hasn’t followed suit: Under state law, non-tenured teachers—sure to be among the youngest in the workforce—must be dismissed before those with tenure are considered. Because Ohio teachers must be licensed for seven years before becoming eligible for tenure, there’s little chance that a district would ever need to consider laying off tenured teachers. Ohio’s long probationary period also has some interesting consequences: On the one hand, it puts high-performing teachers who have been working for the better part of the decade on the chopping block. On the other hand, it gives districts more flexibility to lay off a poor-performing “veteran”—say a sixth-year teacher—instead of a promising novice. Overall, however, the beneficiaries of Ohio’s version of LIFO are senior teachers who enjoy significant job protections during a reduction-in-force. This is true even if they’re less effective than their junior counterparts (remember, tenure status has nothing to do with classroom effectiveness).

Regrettably, due to timing issues and the likelihood that existing contracts would be grandfathered in, Ohio lawmakers likely cannot eliminate LIFO as districts make personnel decisions for the coming year. But they should nevertheless consider revisions to state law that would enable districts to protect all of their best teachers should the current fiscal challenges persist or when they arise again in the future. Two policy options would eliminate LIFO.

Option 1: Eliminate the requirement that districts give preference to tenured teachers in a reduction-in-force. State statute could be amended so that tenure status is not the primary factor in layoff decisions. In line with the policies of other states (e.g., Colorado, Florida, and Texas), Ohio law could instead require districts to dismiss teachers based on performance. In fact, state lawmakers could look to Florida law which reads:

Within the program areas requiring reduction, the employee with the lowest performance evaluations must be the first to be released; the employee with the next lowest performance evaluations must be the second to be released; and reductions shall continue in like manner until the needed number of reductions has occurred.

Language such as this would protect the jobs of high-performing teachers—including early-career educators without tenure—as Ohio districts would be required to first sever ties with their lowest performing teachers during a reduction-in-force. The downside of this option is that it still constrains district flexibility around layoffs, as there may be cases in which a lower-performing teacher might be preferred (for example, if she taught in a high-needs school or in hard-to-staff subject areas).

Option 2: Eliminate all regulations about how districts lay off employees, but prohibit reduction-in-force procedures from being a topic of collective bargaining. Ohio law could give district administration true “local control” over how they address reductions-in-force. In this case, state law would be silent regarding any specifics about which teachers are first laid off, whether by performance, tenure status, or seniority. However, to ensure that districts don’t simply bargain away this management right—and put into contract a seniority based system—lawmakers should also clarify that matters of reductions-in-force are not a permissible topic of collective bargaining. The upside of this option is that it would give districts, much like public charter and private schools, maximum discretion to decide how to downsize. The tradeoff is that a district may still in practice implement a seniority-based layoff process, thus failing to guarantee that the jobs of young, talented teachers are protected.

* * *

In a recent article, one Northeast Ohio superintendent told the press, “We’re resolved to provide the highest quality of education possible for our Lakewood students.” That’s the right attitude in light of a budget crunch. By eliminating an archaic LIFO provision, state legislators could better empower district leaders to make personnel decisions that ensure that their best teachers are in the game—not sitting on the sidelines.

Ohio and other states are working hard to increase the postsecondary readiness of high school students, but it is not at the state level where readiness actually occurs. Schools themselves are the conduit, and their leaders are the providers of readiness pathways, such as early college courses and career training programs. Why then does a significant body of evidence suggest that high school grads remain underprepared for both college coursework and employers’ skill requirements? A new report surveys teachers and principals across the country to get their perspectives on the availability and quality of today’s postsecondary readiness pathways. It indicates that educator complacency may be a big part of the problem.

Data come from spring 2019 surveys administered to nationally-representative samples of public school teachers and principals via RAND’s American Teacher Panel and American School Leader Panel, respectively. Both are part of the Learn Together Surveys, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Specifically, the report covers the responses of 2,141 teachers and 770 principals in charter and traditional district schools serving students in grades nine through twelve. Respondents were asked about the availability and quality of postgraduation transition supports for college and careers, whom they perceive as holding responsibility for student readiness, the extent to which students have equitable access to information and supports, and what changes might be needed to improve access to and quality of transition pathways.

A huge majority of both teachers (87 percent) and principals (72 percent) expressed positive opinions about the quality of their own schools’ supports for students’ future career preparation. There was very little variation in this pattern, with only teachers in high-poverty schools expressing less than overwhelming positivity. However, it is unclear from whence this certainty comes. For example, almost half of the surveyed teachers reported having no information or resources about apprenticeships to share with students, and another 20 percent reported never sharing the apprenticeship information they had with any students. Similarly, more than half of principals reported having no access to data on their students’ postsecondary remedial education or graduation rates. And while most teachers (61 percent) reported that high-achieving students were well supported for postsecondary transitions in general, support rates for underachieving students (32 percent), minority students (43 percent), and low-income students (44 percent) were much lower.

Teachers and principals reported that postsecondary readiness pathways and services were readily available, which include advanced courses like AP or IB, dual enrollment, ACT/SAT prep, college application help, and FAFSA assistance. Supports for non-four-year pathways were also reported to be readily available, but the positivity expressed in that general category of support does not reflect the minimal amount of information sharing reported by teachers to students regarding things like part-time jobs or technical training programs.

In a bit of a surprise, teachers in urban and high-poverty schools reported significantly higher rates of data access than teachers in nonurban and low-poverty schools—things such as FAFSA completers, College Match scores, and SAT/ACT scores. Additionally, high-resource schools do not have more supports for college and career pathways than lower-resourced schools. Instead, school context (rural versus urban areas) and local employment levels were reported as playing a large role in the availability of supports. Principals tended to provide more-favorable responses than teachers about available services.

As to responsibility for readiness, the survey findings are high across the board. Teachers and principals put a high level of responsibility upon themselves for ensuring student readiness, but it is telling that parents were ranked equally high and that students themselves were seen as being even more responsible for it. With the reported gaps in information availability and distribution, this responsibility ranking should raise some alarm bells.

Be it career, college, or military, there is no pathway to postsecondary success that does not go through our nation’s high schools. Principals, teachers, and staff play a critical role in brokering access to college and career information and resources, not to mention providing many of the academic and soft skills needed to access a job or a college major. Thus, schools are responsible for allocating access to supports for each pathway and providing the students they serve with the opportunity to strengthen or combat disparities in both utilization and outcomes. Teachers and principals vary widely on their perceptions of the data they have, the quality of it, and the distribution of that information to their students. All of this bodes ill for the students who look to them for the key to their futures.

SOURCE: Melanie A. Zaber and Laura S. Hamilton, “Teacher and Principal Perspectives on Supports for Students' College and Career Pathways,” RAND Corporation (March 2020).

Back in March, the coronavirus pandemic led to a rare outbreak of a different sort, as bipartisanship returned to Capitol Hill. Unfortunately, unlike COVID-19, that phenomenon has proved fleeting, as Democrats and Republicans are back to bickering again as they debate the next phase of the federal response.

Earlier this month, House Democrats put their chips on the table with a $3 trillion stimulus proposal, dubbed the HEROES Act. The bill passed on May 15, despite Senate Republicans saying that another round of help is premature. The need to provide liability protection for businesses that bring staff back to work prevailed over partisan politics. For his part, Fed chairman Powell is uncharacteristically warning that, without massive federal aid and investment, the present recession will turn into something long-lasting and much worse.

This won’t be the last fight over federal aid and posturing has become par for the course in Washington in recent years. Sometimes it’s the prelude to negotiation, sometimes to stalemate. But we would be remiss not to plead with our fellow conservatives: don’t shoot yourselves—and your constituents—in the foot by refusing to assist state and local governments.

Sadly, GOP opposition to “fiscal stabilization” seems to be hardening. Even Senator Lamar Alexander, a former governor himself and one of the smartest and steadiest Republicans in Congress, has indicated that states might be on their own. “The country certainly can’t afford for Washington to keep passing trillion-dollar spending bills,” he recently told AEI’s Frederick M. Hess. “We are all going to have to make tough decisions.”

Yes, conservatives are right to be leery of bailing out profligate state and local governments, especially for needs that bear little relationship to—and pre-date—the virus crisis and its economic consequences. It didn’t help when Illinois Democrats pleaded for a rescue package for the state’s miserably mismanaged pension system. It’s simply unfair to ask taxpayers in red states to pay the bill for expensive government services in blue ones. If progressives could count on the federal government to come to the rescue during every recession, it would create a moral hazard, giving them even more reason to create expensive programs that their own taxpayers can’t afford.

So the details matter greatly when deciding how federal aid is allocated. Proposals are floating around Washington that address the concerns of Republicans and their constituents, while keeping the focus squarely on the matter at hand: backstopping the sizable COVID-related expenditures of hard-hit state and local governments, and replacing the billions of dollars of revenue lost when the economy shut down. In other words, a well-crafted bill would base the amount of funding for state and local governments upon an estimate of the actual costs and losses incurred as result of the pandemic. It cannot be a blank check to fund every item on a state’s wish list.

But telling states to “make hard decisions” is not going to cut it, for four reasons.

First, this is not a typical crisis for which state and local governments could prepare. The economic shock is orders of magnitude greater than during a typical, cyclical downturn; no public official—not even in solidly red states like Ohio—could have set aside nearly enough “rainy day funds” to weather this storm. The federal government has the ability to borrow the money to deal with a calamity of this size; state and local governments don’t. And, unlike Congress, they must balance their budgets.

Second, without federal aid, states and localities will be forced to make enormous cuts to staff—and that will in turn slow down the economic recovery. To get business moving again, once it’s safe to resume activity, we’ll need more consumers with money in their pockets and the confidence to spend it. Laying off hundreds of thousands of state and local workers—including front-line teachers, police, nurses, and firefighters—won’t help.

Third, cuts in staff means a cut in services and the burden of those cuts will fall hardest on our communities and families most in need. Crime-ridden streets will be less safe, fragile families will be more stressed, and low-income students will lose ground academically—a double whammy considering the time they’ve already lost to school closures. It will also make it harder to reopen the economy if basic services like building and health inspectors are in short supply.

Finally, Republicans could pay a big price in November if they block such help, given its wide public support. Are they really willing to gamble away important swing states like Michigan or Senate seats like Arizona’s when the headwinds are already so fierce?

By all means, GOP leaders should push back against the parts of stimulus packages they find objectionable, and make sure that any state or local aid doesn’t go to bail out pensions or keep afloat other long-insolvent big-government programs. But as defenders of our federalist system and of local control, it makes no sense to allow our state and local institutions to crumble. Federal aid should always be a measure of last resort, reserved for times of true national crisis. Alas, fellow conservatives, that time is now.

Editor’s note: This post was first published by The Bulwark.