The anti-voucher lawsuit misleads when it comes to segregation

In the early days of January, a coalition of traditional public school districts filed a lawsuit aimed at striking down

In the early days of January, a coalition of traditional public school districts filed a lawsuit aimed at striking down

In the early days of January, a coalition of traditional public school districts filed a lawsuit aimed at striking down EdChoice, Ohio’s largest voucher program. As is typically the case, their claims run the gamut of anti-choice rhetoric and rely on inaccurate and misleading data. But they are particularly disingenuous when they claim that EdChoice “discriminates against minority students by increasing segregation in Ohio’s public schools.”

The lawsuit contends that “a disproportionate percentage of non-minority students” use EdChoice. But based on statewide data, that’s not true. Consider data from 2018–19, the last school year that wasn’t impacted by Covid-19. During that year, 16 percent of students in districts statewide were Black, and 6 percent were Hispanic. Within the EdChoice program, however, 38 percent of the participants were Black and 11 percent were Hispanic. That means the percentage of Black students participating in EdChoice was more than double the statewide district average. The percentage of Hispanic participants was nearly double, as well. Compared to statewide demographics, EdChoice students are disproportionately Black and Hispanic.

If that’s the case, then how can the lawsuit claim otherwise? The short answer is that the plaintiffs are focused on district-level data because they believe it strengthens their case. Specifically, they argue that, since the advent of EdChoice, “the percentage of minority students in many of Ohio’s public school districts has increased disproportionately relative to the communities where they reside.” As evidence, they cite the districts of Richmond Heights and Lima, where the percentage of White students has dropped and the percentage of students of color has increased. They also point out that Columbus City Schools has experienced a nearly 10 percent drop in its percentage of White students.

The plaintiffs seem to believe that these population changes can only be explained by White students using EdChoice vouchers while all other students are forced to remain in public schools. But there are two problems with such logic. First, the plaintiffs cite overall district demographic data, but offer no demographic data on their EdChoice students. If the point of the lawsuit is to prove that a “disproportionate percentage of non-minority students” use EdChoice, then disaggregated EdChoice numbers are crucial. Without them, there’s no way to verify the claim. The plaintiffs don’t cite these data, but my colleague Aaron Churchill does in a previous analysis of EdChoice and segregation. He found that in Columbus City Schools—the district explicitly cited by the lawsuit as evidence that EdChoice “exacerbated segregation in previously desegregated districts”—voucher recipients are demographically similar to their district peers. Sixty-seven percent of students in the district were either Black or Hispanic, while 68 percent of voucher participants were Black or Hispanic.

Second, the plaintiffs fail to provide evidence that it was EdChoice—and not myriad other social or economic factors—that caused these shifts in district demographics. Any education researcher worth their salt will tell you that correlation doesn’t equal causation. Much as they might want to, voucher opponents can’t rattle off enrollment trends from three districts between 2006 and 2021 and claim that it’s proof that the program has caused segregation in these districts, much less the state as a whole.

Moreover, there’s plenty of data indicating that the entire nation has been experiencing similar shifts in demographics over the last twenty years. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, the percentage of public school students who were White decreased from 54 percent to 47 percent between the fall of 2009 and the fall of 2018. Meanwhile, the percentage of students who were Hispanic increased from 22 to 27 percent, and the percentage of students who were Black decreased from 17 to 15 percent. In 2014, a piece published in The Atlantic noted that, although 62 percent of the total U.S. population had been classified as non-Hispanic White during the previous year, minority students—identified as Hispanics, Asians, African Americans, Native Americans, and multiracial individuals—would account for over 50 percent of public school students in the fall.

Ohio data reflect these national trends. In 2006, statewide public school enrollment for White students clocked in at over 1.3 million. By 2021, that number had dropped to just over 1 million, equivalent to a loss of over 273,000 students and a 20 percent decrease. During that same time period, enrollment for Hispanic students skyrocketed by 162 percent, from just over 41,000 students in 2006 to nearly 108,000 in 2021. Enrollment for multiracial students increased by more than 47,000 students (a 102 percent jump), while enrollment for Black students decreased by just over 23,000 students (an 8 percent drop).

The upshot? At both the national and state level, there are fewer White students in public schools this year than there were in 2006. And while it’s true that voucher usage in Ohio has increased during that time period, the size of EdChoice is hardly enough to account for the state-level demographic shifts outlined above. Remember, despite serving about 50,000 students today, EdChoice represents only 3 percent of the total public school enrollment in Ohio. Broader population trends are almost certainly playing a much greater role in demographic changes than EdChoice.

If voucher opponents want the courts to dismantle a school choice program that serves tens of thousands of students each year on the basis of segregation, they need more than conjecture and incomplete data. Based on their complaint, they’ve failed to bring any hard evidence that supports their accusations. With any luck, the courts will ignore their flimsy claims and see the lawsuit for what it is: a politically motivated, half-baked attempt to kill educational choice for thousands of Ohioans.

For decades, analysts have observed large achievement gaps between low-income children and their peers, disparities that have only widened due to Covid. To address these gaps, there is universal agreement that low-income students require additional resources to support their education. To its credit, Ohio has long provided additional state funding to public schools that serve more economically disadvantaged students. This year, for example, the state will send Ohio schools roughly $450 million in supplemental dollars through a funding stream known as DPIA, or “disadvantaged pupil impact aid.” DPIA will increase in FY 2023—and beyond, if lawmakers continue phasing-in the state’s new funding model.

Providing extra dollars for low-income students is important, but how schools spend those funds also matters greatly. As Eric Hanushek of Stanford University told Ohio lawmakers last year, “How money is spent is more important than how much is spent.” His claim is backed by numerous studies indicating that some interventions, programs, and educational “inputs” deliver more bang for the buck. The most obvious example is teacher quality, where studies find that their “value-added”—i.e., their contributions to student achievement—vary widely from teacher to teacher. Thus, dollars spent to retain high-performers are being used more productively than dollars spent on low-performers—or increases that go to everyone, indiscriminately. Another example is tutoring. Whereas “high-dosage” tutoring raises pupil achievement, poorly designed tutoring programs have proven to be ineffectual.

So are Ohio schools spending funds wisely? A recent report from the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) offers some insight, at least with respect to DPIA funding. But the report’s data—and the lack thereof—also raises questions about the state’s approach to this important program. It’s clear that Ohio could be doing more to ensure that DPIA dollars are used to improve the outcomes of economically disadvantaged students.

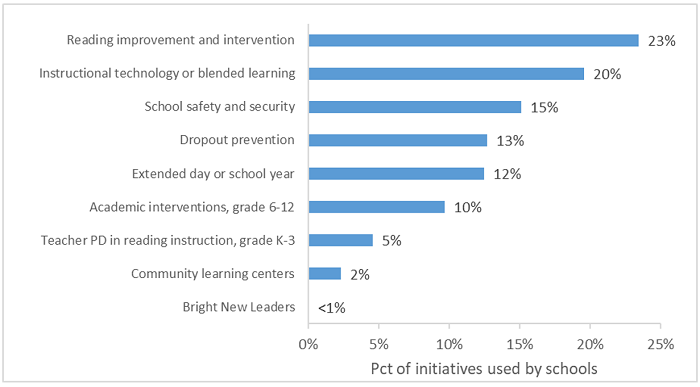

First consider the chart below, which displays the key data point presented in the ODE report. The figure shows a breakdown of initiatives that schools undertook with DPIA funds. The most common usage was reading improvement and intervention (23 percent of the initiatives reported by Ohio schools), with IT and blended learning coming in a close second. The least used options were creating community learning centers or hiring a principal trained through the Bright New Leaders program.

Figure 1: How Ohio schools used DPIA funds in fiscal years (FYs) 2020 and 2021

Source: Ohio Department of Education.

A few observations:

As it currently stands, the spending policies for DPIA are a mush. On the one hand, the spending requirements are too vague to encourage initiatives that studies suggest have the most impact on student learning. Yet at the same time, they might also be overly restrictive. The categories could be pushing schools into spending on mundane activities such as professional development or basic goods like Chromebooks and computer software, while limiting more creative or better uses of these resources. Taken together, there seems to be lack of clear expectations and accountability measures that ensure these funds are used to better the outcomes of Ohio’s low-income students.

Ohio lawmakers should change their approach to DPIA. (Note, they also need to address problems with the enrollment data used to allocate these funds to better target DPIA funds.) In my view, legislators could pursue one of two options.

Option 1: Get strategic and specific about DPIA spending uses. Under this approach, the legislature—likely with expert advice—would set forth a limited number of specific uses of these funds. Only initiatives that have clearly demonstrated effectiveness would be included. This option, however, would place greater constraints on schools’ spending alternatives, such as discouraging them from combining DPIA dollars with other funding streams in efforts to create a more comprehensive spending strategy. The option could easily open debates about which practices are most effective and worthy of inclusion. That being said, by requiring schools to use funds on only proven practices, it holds potential to improve student outcomes. The following list offers an idea of what categories might be included as approved spending uses:

Option 2: Provide maximum flexibility but demand more rigorous oversight and accountability. Another approach—the polar opposite of the one above—is to remove all requirements and give schools full discretion over spending. The upside to this option is that schools could deploy resources to meet evolving, on-the-ground needs of students. Unlike the more constrained option above, this option would encourage schools to combine DPIA with other funding streams rather than seeing DPIA as discrete “add-on” dollars. The obvious risk is that schools will make poor decisions. To guard against this, lawmakers could demand stronger accountability for student outcomes and task ODE with more rigorous oversight of DPIA spending (while setting aside a small portion of funds to support its new responsibilities).

One legislative option could entail putting more teeth into a current statute that requires the agency to flag districts and schools that produce unsatisfactory results for economically disadvantaged students.[2] Under current law, the only requirement of such “watch” schools is to submit an improvement plan to ODE. There are no consequences. Lawmakers could fix this by demanding a formal state evaluation of DPIA spending in districts and schools that are consistently on the “watch” list. They could also charge ODE with offering, based on its evaluation, recommendations and supports that would require (or strongly encourage) schools to adopt effective practices and programs. Last, in cases of chronic underperformance, the legislature could even require DPIA funds to be withheld.

***

Over the years, Ohio has commendably directed more state aid to schools that serve higher numbers of economically disadvantaged students. Under the new school funding system, it’s poised to steer even more dollars that way. Unfortunately, though, the state has done too little to ensure that schools are putting these dollars to good use. Revisiting the spending requirements and oversight policies for DPIA should be on policymakers’ agendas this year. The approaches outlined above would require bold and steady leadership, but making sure schools leverage funds to benefit low-income students is crucial to ensuring great educational opportunities for all.

[1] Due to recent changes in state law passed last year, schools have eight additional options (largely related to mental health and social-service supports), which were incorporated from the state’s former Student Wellness program. Schools must now also create a plan for using DPIA funds in collaboration with another public or nonprofit agency.

[2] This is in addition to the federally required identifications of low-performing schools (i.e., “comprehensive” and “targeted” school improvement).

After the Brown v. Board of Education decision, school desegregation efforts in Detroit followed a familiar pattern: Busing of students to achieve racial balance was proposed, resistance and White flight occurred, and somebody sued. Milliken v. Bradley was finally decided in the U.S. Supreme Court in 1974, rejecting the idea that outlying districts had to be part of Detroit City Schools’ desegregation solution. A city-suburb divide thus persists to this day, with school district lines approximating historically redlined housing boundaries.

Though the percentage of Black suburban residents has grown, the metro Detroit area remains one of the most segregated in the country. Over 80 percent of Detroit students today are Black, while over 60 percent of suburban students are White. The rise of school choice in the 1990s, meant mainly to provide better school options for underserved students, could also have chipped away at this geographic divide. A new report from Wayne State University researchers Jeremy Singer and Sarah Winchell Lenhoff looks at data on interdistrict open enrollment and suburban charter school attendance to see whether the divide has been meaningfully breached.

Michigan is ranked fairly highly by NAPCS in its most-recent report on model charter school laws across the country, and charters in the state are numerous, with few geographical constraints. Interdistrict open enrollment is more limited, as districts are allowed to remain closed entirely to transfer students or to limit the number of non-resident enrollees. The researchers suggest unrestricted “administrative burdens” also limit enrollment, even in districts that are ostensibly “open.” Furthermore, Michigan law does not require either sending or receiving districts to provide transportation, access to which is a huge problem in this sprawling metropolis, even for district residents staying put. The good news is that many students seem to have overcome these barriers. Previous research by Lenhoff shows that nearly one in four Detroit resident students attend school in the suburbs.

The new report uses statewide student attendance and census data from the 2015–16 school year to compare public school choices, resident addresses, and various school quality measures. Overall, 22,170 resident students left Detroit that school year to attend a public school option in the suburbs. The vast majority of exiters were Black, and much smaller percentages were Hispanic and White. It should be noted that, per state law, the category “White” includes Arab American students of Middle Eastern and North African heritage. Data indicate that members of these communities—large and concentrated in a specific part of the Detroit metro area—drive the exit patterns observed for White students. Sixty-three percent of exiters attended suburban charters, while the rest enrolled in suburban district schools. A whopping sixty-six different suburban districts received at least one exiter, but more than 50 percent of all exiters went to one of just four border districts: Southfield, Oak Park, Harper Woods, and Dearborn. The average exiter had to travel 4.5 miles to school each day, compared to 2.3 miles for Detroit resident students staying put and 2.0 miles for suburban resident students.

In “open” districts—that is, ones with little or no known restrictions in place to limit enrollment from outside their borders—slightly more exiters landed in a district school than in a charter. In “managed” districts where formal or informal limits exist, nearly 60 percent of exiters attended charters. And, somehow, 5 percent of exiters landing in a “closed” district still managed to get a seat in that district (think, for example, children of district employees), while the other 95 percent in those districts understandably went to charters.

Compared with their known set of school choices available within Detroit, the average exiter chose a school with slightly lower levels of racial isolation and about the same level of economic disadvantage. When it came to school quality, exiters, on average, enrolled in schools with a slightly lower discipline rate, a slightly higher stability rate, and somewhat better average math and English language arts state test scores. Singer and Lenhoff, however, express concern that Black exiters experience lower school quality than White, Hispanic, and Asian peers who likewise exit Detroit schools. Unfortunately, the nuances of quality ratings among schools are not included here, so it is difficult to ascertain the full measure of the gap; hopefully future research will illuminate these details. So the while primary goal of school choice programs—better schools for chronically-underserved students—seems generally to be reached, any deeper aims remain elusive.

The researchers specifically discuss the observation that exiters are “isolated” in their new schools—by which they mean Detroit resident students are not integrated with suburban resident students despite crossing borders. This is an important point. Exiters do attend suburban schools where an average of 51 percent of their classmates are also Detroit residents. A bit surprising, perhaps, but not outside the realm of possibility. One can surmise without too much concern that suburban families don’t choose charters (in 2015–16, that is; things may have already begun changing in that regard), but the possibility that school districts may be funneling their open enrollees to separate buildings does raise an eyebrow. While not proven by the data at hand, that possibility could be easily eliminated with common sense tweaks to open enrollment – including eliminating closed borders except in cases of buildings over capacity – which empower parents and limit longstanding “opportunity hoarding” often associated with high-cost housing zones and the districts that have historically arisen from them. Very likely, such changes would also allow exiters to land in even better new schools, accomplishing both the primary and secondary aims of public school choice.

SOURCE: Jeremy Singer and Sarah Winchell Lenhoff, “Race, Geography, and School Choice Policy: A Critical Analysis of Detroit Students’ Suburban School Choices,” AERA Open (January 2022).

A recent release from the Education Commission of the States reminds us that the term “virtual school” refers to several different types of educational options, and that the ecosystem—more important now than ever before—requires specific attention and support from policymakers.

The four main types of virtual schools are charter schools, single-district schools, multi-district schools, and state schools. Governance structures vary across the typologies, with a variety of agencies and actors responsible for oversight and implementation, including state education agencies and state boards of education, charter school authorizers, local education agencies, and third-party providers.

Charter schools constitute nearly half of all full-time virtual schools in the U.S. and have the largest enrollment share. As of January 2020, more than twenty states permitted virtual charters (with more potentially on the way). Their operation and governance are generally akin to brick-and-mortar charters, with a mix of nonprofit and for-profit management organizations. Single- and multi-district virtual schools are rarer and clearly different from charters. Virginia and Tennessee, for example, permit a district or group of districts to contract with entities that meet state standards to serve as the online provider while the districts maintain oversight. The Florida Virtual School (FVS) is the prime example of a state-sponsored virtual school. It is run by a governor-appointed board with oversight from the state department of education. And the pandemic pivot to remote learning has allowed it to expand far beyond the Sunshine State.

A quick rundown of recent research on virtual education leads with the bad news that a raft of studies have shown that students in virtual charters experience weaker academic growth, increased mobility, and lower graduation rates than their brick-and-mortar peers. Specifically, virtual schools that focus on independent study and asynchronous instruction with limited student engagement and teacher contact time, high student-teacher ratios, and a reliance on family support for learning all experience poorer academic outcomes. However, evidence also suggests that course content and student motivation matter greatly. A Michigan study showed that part-time virtual students—those supplementing in-person learning with specific online content—fared better than their full-time virtual counterparts, while a study of FVS found far stronger positive outcomes for non-traditional students working on credit recovery versus traditional, first-time course takers.

The guide ends on a reasonably positive note by providing evidence that state-level policy levers are an effective means by which to implement improvements to virtual schools. State-level standards for school—and in the case of charter virtual schools, for their authorizers, too—can support research-driven initiatives, such as differentiated instruction and student-teacher contact time; flexible definitions of attendance and progress monitoring; teacher training and licensure requirements designed specifically for remote instructors; and funding mechanisms that prioritize virtual-specific needs, such as one-to-one student technology access, in-person testing, and at-home enrichment activities.

No state is pulling out all of these various stops, but best practices from across the country are described in the guide. Prior to the plague, virtual schools were expanding in a slow and organic way. The policy infrastructure to properly support them was, perhaps, lagging behind, but the right moves were being made in that regard. While the recent explosion of virtual schooling was involuntary, exponential expansion is inevitable, even after the Covid danger has subsided. Now is the time to make sure we understand how virtual schooling works best and make sure states guarantee the highest functionality of virtual options for all families who want it.

SOURCE: Ben Erwin, “A Policymaker’s Guide to Virtual Schools,” Education Commission of the States (November 2021).

Giving children an excellent K-12 education has long been a top priority for Ohioans. That’s no different today, but educational issues loom even larger after the pandemic-related disruptions of the past two years. To guide productive conversations about improving education, clear and accessible data are key. In that light, we are pleased to present Ohio Education by the Numbers. Now in its fifth edition and updated for 2022, this publication contains data that shed light on the trends and present needs of students, as well as the investments that Ohioans have made to ensure that all children have opportunities to achieve their dreams.

Whether you’re a lawmaker, reporter, community or business leader, or a parent or grandparent, this booklet is designed for you. As a readily accessible resource, we hope you’ll find it to be a go-to guide as you discuss education in your community.

You can download a PDF version of the booklet using the link to the right and view these data online at our companion webpage, www.OhioByTheNumbers.com.