The feds’ proposed changes to CSP will hurt Ohio charters

For nearly three decades, the federal Charter Schools Program (CSP) has offered grants to support brand-new charter schools and, more recently, high-quality n

For nearly three decades, the federal Charter Schools Program (CSP) has offered grants to support brand-new charter schools and, more recently, high-quality n

For nearly three decades, the federal Charter Schools Program (CSP) has offered grants to support brand-new charter schools and, more recently, high-quality networks looking to expand and serve more students. With a price tag of $440 million per year, it’s a drop in the bucket compared to the $60 billion the federal government spends on education. But it’s hard to overstate just how critical these dollars have been to charter schools—and how damaging it would be if the program were to disappear.

Congress approved another $440 million for CSP last month, so the program itself isn’t going anywhere. But the next day, the Biden administration proposed an entirely new and unprecedented set of rules that could make it close to impossible for charters to access the funding. Add to that a comment period that’s unusually short (only one month, compared to the usual two), and the fact that the charter school community wasn’t consulted about these changes (despite the proposed rules emphasizing the importance of collaboration and criticizing charters for failing to “fully engage” stakeholders), and it’s not hard to see why advocates are outraged.

In Ohio, the fallout of these new regulations could be steep. Even after a massive overhaul of the school funding system, Ohio charter schools are still shortchanged, receiving about 75 cents on the dollar compared to their traditional public school counterparts. Finding and securing a facility is a daunting task even for well-established charter networks, let alone start-up schools. Recruiting quality staff has always been a challenge, and the pandemic has only exacerbated the problem. Nevertheless, research shows that brick-and-mortar charter schools in Ohio outperform their district counterparts. Perhaps most importantly, they offer quality opportunities to Black and Hispanic students from low-income families.

The last thing the Ohio charter sector needs is for the feds to make it even more difficult for start-up schools and expanding networks to obtain funding. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what would happen if the proposed CSP rules go into effect. Here’s a closer look at two of the most problematic areas.

Prioritizing collaboration with districts

Under the new rules, priority will be given to CSP applicants who “propose to collaborate with at least one traditional public school or traditional school district in an activity that is designed to benefit students and families.” As part of their applications, charters seeking priority would need to provide a letter from a partnering school or district that demonstrates a commitment to collaborate. There is no requirement for districts to agree.

The motivation behind this requirement is purportedly evidence-based, as research shows that collaborations among charter schools and traditional public schools “have the potential” to improve the quality of both. The examples outlined within the rules (sharing curriculum resources and instructional materials, creating common systems of professional development, and establishing a joint transportation system) undoubtedly have a ton of “potential.” But only as voluntary endeavors. It doesn’t take a graduate degree in public policy to foresee the incredibly lopsided power dynamic this rule would create. Like it or not, most districts view charter schools as direct competition. This rule would give them the power to shut new and expanding charters out of a critical funding stream just by refusing to collaborate.

This is especially worrisome in Ohio, where the playing field is already uneven. On the one hand are charter schools, which receive less funding on the dollar and consistently fight uphill battles to secure affordable facilities. On the other hand are districts, which have a vested interest in limiting any and all competition. Charter start-ups and networks looking to expand need CSP funding and have every incentive to seek out collaboration opportunities. But traditional public schools have no incentive to agree. In fact, they have every incentive not to agree because this rule does what their lawsuits, restrictive laws, repeated refusal to follow the rules, and misleading media attacks have failed to do—it gives them an easy (and legal) way to squash charter growth.

Community impact analyses

Under the proposed rules, CSP applicants would be required to provide a community impact analysis as part of their application. Among the many items that each analysis must contain are requirements to describe the community’s “unmet demand” for a charter school (including “any over-enrollment of existing public schools”) and to provide evidence that the number of charter schools to be opened “does not exceed the number of public schools needed to accommodate the demand in the community.”

The implication of these requirements is clear: Charter schools should only exist in places where district schools are over-enrolled and additional schools are needed to pick up the slack. (Which, currently, is almost nowhere.) That may be a common viewpoint of choice opponents, but it should not be the policy of any federal agency charged with upholding the law. ESSA, the main federal law governing K–12 education, authorizes CSP under a section entitled “expanding opportunity through quality charter schools.” It explicitly states that the purpose of the section is to “provide financial assistance” to charters and to “increase the number of high-quality charter schools available to students across the United States.” There is no provision stating that financial assistance to charters should be limited to certain locations. The law calls for evaluating “the impact of charter schools on student achievement, families, and communities,” but the proposed regulations conflate “community impact” with district enrollment numbers. It’s a clear signal that the current priority in D.C. is the wellbeing of the system and not the wellbeing of students.

Furthermore, it should concern stakeholders of all political stripes that this rule seeks to set a single federal standard for “community impact.” We live in a nation of unique realities. The education landscape in Ohio is very different than the landscape of California, Oklahoma, or Connecticut. Even within Ohio, there are dozens of contexts. Cities like Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati have varying needs that are often different from those in suburban, small-town, and rural communities. Buckeye State policymakers have a difficult enough time crafting state policy to address the vastly different realities within Ohio. What on earth makes the feds think that they can accurately and fairly evaluate hundreds of local communities without knowledge of the local contexts? It’s an incredible overreach.

The real “community impact” at play here is suffocating CSP with red tape so that communities like Cleveland and Columbus will have fewer high-quality charter school options. Children living in neighborhoods in Dayton and Toledo, in communities in Appalachia, or small towns like Mansfield or Marion will continue to be stuck with the status quo. In 2018–19, the last year Ohio issued state ratings, a whopping 485,680 Buckeye students attended public schools rated an overall D or F by the state. Those children deserve better options regardless of whether enrollment in their resident district is impacted.

***

If the Biden administration believes charters are only worth investing in if they accommodate “demand” for a certain number of public schools, then it has fundamentally misunderstood the driving force behind the choices that millions of American families make each year. Any parent with a school-aged child will tell you that not all schools are created equal. District schools don’t automatically meet kids’ needs just because they are district schools, and charter schools that offer a traditional approach are no less valuable to parents just because they’re located in a district with flat or declining enrollment. In the same vein, assuming that districts will team up with charters just because it’s “potentially” good for kids is naïve at best and sabotage at worse.

CSP was enshrined in law via a rare bipartisan effort. That law is clear: The Department has an obligation to make funding available to quality charter schools. Student enrollment trends and the monopolistic tendencies of traditional public schools cannot and should not have any bearing on that.

Due to massive financial woes, Ohio suspended cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) for retired teachers in July 2017. At that time, the State Teacher Retirement System, or STRS, had racked up a staggering $24 billion in pension debt—i.e., “unfunded liabilities,” the difference between promised retirement benefits and the assets available to pay them.

Suspending COLAs—and a booming stock market—has slightly improved STRS’s finances. But the system remains $21 billion in the hole as of July 2021, and the absence of COLAs, combined with significant spikes in inflation, has left many retirees understandably upset. In response, last month STRS approved a one-time 3 percent COLA. That adjustment should bring some relief, but it’s only half of what social security gave retirees last year (Ohio teachers don’t participate in social security). It must be emphasized that this is a one-time adjustment—not an ongoing promise. System leaders likely balked at the fiscal implications of anything more permanent, as actuaries estimate that an ongoing 2 percent COLA would add another $14 billion to the system’s liabilities. Yikes.

The latest skirmish over COLAs is just one symptom of an ailing system. Not only are teacher pensions in Ohio underwater and disadvantaging retirees, but they also exact a financial toll on school districts and current teachers.

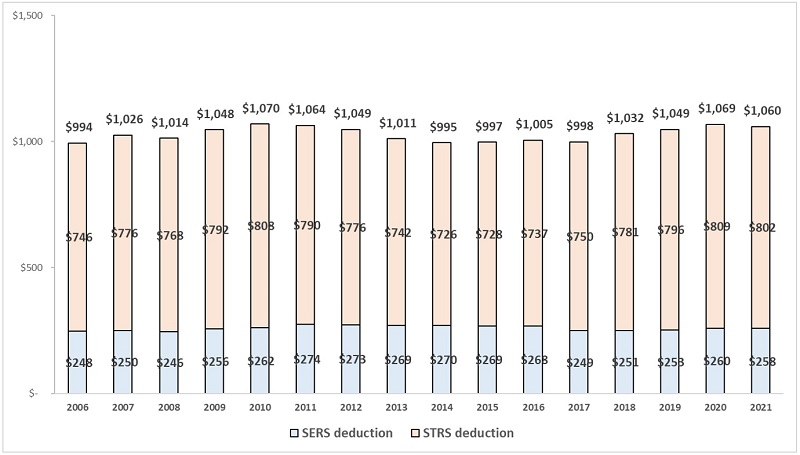

Let’s start by looking at the cost to employers. Ohio requires school districts to pay 14 percent of their payroll to state-run retirement systems, whether the one for teachers (STRS) or for other school employees (SERS). This “payroll tax”—as one might call it—cost districts $1.6 billion in FY21. That amounts to just over $1,050 per pupil or about 8 percent of their overall operating expenses. Interestingly, districts’ pension costs have remained largely flat over the past fifteen years, likely reflecting a constant employer contribution during this period. The per-pupil amount Ohio districts spend today on pensions tracks fairly closely with the national average.

Figure 1. Employer share of pension costs per pupil, Ohio school districts, 2006–21 (inflation adjusted)

Source: Author’s calculations based on Ohio Department of Education, Statements of Settlement for traditional school districts and their enrollment data. Dollars are inflation adjusted to 2021 prices using the consumer price index. This figure only reflects the employer’s share to pension costs (it does not include the worker’s share).

Analysts have long raised concerns about committing such sizeable sums for pension payments, as it crowds out other uses of school funds. To illustrate, consider what would happen if Ohio reduced the required district contribution to 12 percent, a rate closer to the average private employer’s contribution (social security tax plus retirement benefits). This would free approximately $170 million per year for districts, an amount that would allow for a salary increase of $1,700 for every Ohio teacher.[1] Given STRS’s fiscal problems, reducing the employer contribution is unlikely. Yet the example illustrates how pensions saddle schools with inflexible costs that restrict their ability to pay higher salaries or meet other critical needs.

But the employer side is only half the story—and half the cost. The “true” per-pupil expense of the pension system is nearly double what is shown in Figure 1, because Ohio teachers are required to contribute 14 percent of their salary to STRS and nonteaching staff pay 10 percent to SERS. Thus, school districts and their employees together pay approximately $2,000 per pupil for pensions.

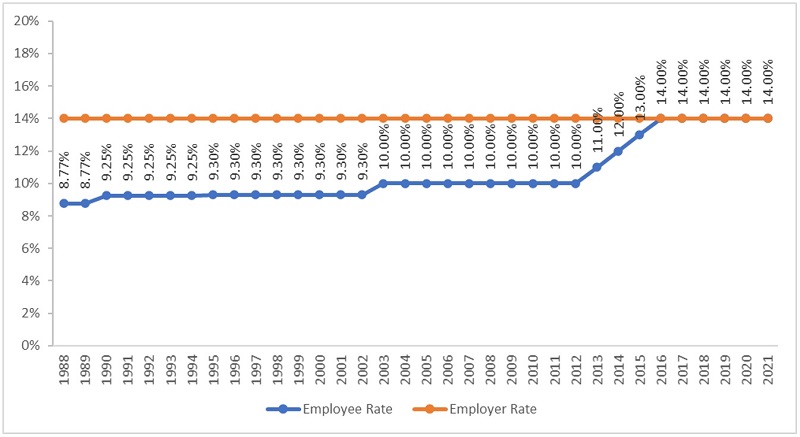

Unlike the employer rate, teachers’ required contributions have steadily increased over time. Figure 2 shows that back in 1988, Ohio teachers paid a relatively modest 8.77 percent of their salary into the pension system. That rate has climbed since then and now stands at 14 percent.

Much like higher taxes, increasing the employee contribution rate reduces the take-home pay of teachers. For an Ohio teacher earning the state average salary of $65,000 per year, a 14 percent contribution subtracts $9,100 from her annual salary. On top of that are federal and state income taxes, property taxes, and…well you get the story. There’s not all that much left. Of course, it’s not uncommon for workers to be required or incentivized to fund retirement. But even if the contribution rate for Ohio teachers was 10 percent—STRS’s employee rate from 2003–12 and SERS’s current rate—it would put $2,600 more per year in the average teacher’s pocket.

Figure 2. STRS employer and employee contribution rates, 1988–2021

Source: STRS Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports.

Ohio’s teacher pension system is a massive expense for schools and teachers—and it doesn’t even reliably deliver benefits to help retirees deal with inflation. We don’t have the space here to discuss the ways that pension systems cheat young teachers or those who leave the profession earlier than the retirement age (topics for another day). And as pensions expert Chad Aldeman found, Ohio teachers—even those who stay to retirement age—would actually be better off choosing the state’s rarely used 401(k)-style plan. Given the high costs and mediocre benefits, one might ask the following: Is it time for something better? Ohio does have policy options besides continuing this legacy system, and I’ll discuss those in a future piece.

[1] In FY 21, Ohio districts paid $1.20 billion into STRS, implying their teacher payrolls were $8.57 billion (0.14 * $8.57 billion = $1.20 billion). Reducing the employer contribution to 0.12 would have cost districts $1.03 billion in teacher retirement payments. The difference ($1.20–$1.03 billion) is divided by the roughly 100,000 teachers in Ohio yielding a potential raise of $1,700 per teacher.

A 2018 Pew Research Center study demonstrated the perhaps surprising fact that the United States remains a robustly religious country, indeed the most devout of all the wealthy Western democracies. Ours was the only country out of 102 examined that had higher-than-average levels of both prayer and wealth. And while average rates of religiosity are declining and people are increasingly identifying as religiously unaffiliated, the percentage of Americans who are deeply religious has remained steady. Also perhaps surprising: This includes something like one quarter of all teenagers. In her new book, God, Grades, and Graduation, sociologist Ilana M. Horwitz delves deeply into teens’ lives in search of potential connections between religiosity and educational outcomes.

Primary data come from the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR). Beginning in 2002–03, NSYR surveyed 3,290 kids between thirteen and seventeen, as well as one of their parents. Analysts collected four waves of data, completing the study in 2012–13. Horwitz connects NSYR respondents with data in the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) to track college attendance and outcomes. She also included data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Add Health, based at the University of North Carolina, surveyed approximately 20,000 students in grades 7–12 and one of their parents starting in 1994–95 and has continued to follow them over the past twenty-five years.

Horwitz focused her analysis on Christianity, as it is the most common religious affiliation reported in the U.S and encompasses a huge number of denominations and subgroupings. She is most interested in religious intensity, breaking out her subjects into three groups: atheists, non-religious theists, and the group she calls “abiders”—those who expressed the deepest, most life-encompassing faith. The bulk of the book looks at abiders—including numerous case studies of individuals across the socioeconomic, social class, and geographic spectra—and how their faith has intersected with their education trajectories. In a nutshell, strong religious faith appears to boost students’ educational attainment in high school—both GPA and graduation—while constraining their postsecondary outcomes.

Horwitz makes the case that the main purpose of secondary school is not gaining knowledge or critical thinking skills but learning how to behave and perform in a rules- and standards-driven environment. Specifically, schools tend to reward students for their ability to demonstrate certain “values, dispositions, and tastes that characterize the middle and professional class.” She goes so far as to suggest that these are the hallmarks of the “White Protestant status culture” upon which the public common school was founded. Who better to flourish in such an environment than those for whom the same ideals—cooperation, conscientiousness, good behavior, self-discipline, and high motivation—are practiced deeply at home and at church? Evidence suggests that these traits, when internalized and fully embraced, act as “guardrails” against negative behaviors and replicate aspects of the “social capital” enjoyed by higher income youth among those who may lack resources and supports and thus may typically be at risk of falling through the cracks.

Merit-based achievement in school is typically found in greatest supply among those already at the top in terms of family advantage. But evidence abounds in NSYR that those who follow the rules laid down by God, parents, and adult authorities gain an academic advantage—an approximately 10 percentage point bump over non-abiders—in course grades and GPA. This bump exists for both genders, all races, and for students from all socioeconomic strata. The same bump cannot be found in test scores—God won’t give out answers to the algebra final no matter how zealously one prays—but all the subjective measures that go into teachers’ final grades seem to be positively impacted.

However, the abider advantage takes an interesting turn after students step off the high school graduation stage. While thirty-two of every one hundred non-abiders in NSYR earned a bachelor’s degree, forty-five of every one hundred abiders did the same. So far so good. But abiders significantly “undermatch” in terms of college matriculation. Those who took home As and Bs in high school earn degrees from colleges with entering students’ average SAT scores 22 points lower than the average at colleges attended by comparable non-abiders who also got As and Bs in high school. Despite the high school advantage they experienced, abiders are going to (and graduating from) less-selective colleges. This is especially true of high-income abiders, whose double advantage is largely set aside and whose undermatch was largest of all.

Part of it, Horwitz argues, is that college is less about following the rules and more about doing the academic work. Test scores still matter for upper echelon institutions, devaluing the observed abider advantage. But abiders also reported being less interested in being accepted at more selective colleges—even those with the requisite SAT scores. A lack of interest on the part of many abiders in leaving home to attend a college that’s far away from family, church, and community—especially a college that’s perceived to be rife with distraction or temptation—drives this mindset. Living at home and commuting to Hometown U fills the bill just fine. Anecdotes from numerous abiders in NSYR show them ceding agency in their future to God. The goals that their faith has led them to adopt don’t call for rigorous postsecondary education, and even those with degrees were often in low-wage jobs in their mid-twenties as they awaited the call for whatever came next. Income levels for abiders in the workforce were markedly lower than their non-abider peers with similar educational attainment—the largest gaps once again concentrated among students from higher-income families. This likely comes from both the caliber of institutions from which they graduated as well as their post-graduation job choices.

Expression of religious faith takes many forms in America today. Horwitz’s deep dive into the lives of devoutly religious Christian young people clearly shows how faith interacts with important aspects of their lives, including education. The book covers a lot of ground and is a recommended read for any who have an interest in the topic and want to understand the academic journeys of students today.

SOURCE: Ilana M. Horwitz, God, Grades, and Graduation, Oxford University Press (2022).

Over the last several years, cities and states across the nation have invested enormous amounts of time, money, and energy in public and private efforts aimed at increasing postsecondary attainment. Many initiatives have focused on removing barriers like cost. But a paper entitled The Big Blur, published last June by Jobs for the Future (JFF), argues that the greatest barrier is the “seemingly intractable disconnect” between high school, higher education, and the workforce.

The transition to higher education is a rough one. Free community college initiatives remove the barrier of tuition but don’t cover living expenses. Only 25 percent of students in the graduating class of 2021 met all four of ACT’s college readiness benchmarks, and unprepared students often end up in remedial courses that aren’t worth credit but still cost money—and tend to be ineffective to boot. Unlike affluent students with plugged-in parents and fancy college counselors, low-income and working-class kids are expected to track down a wide array of financial, academic, logistical, and other resources on their own, and are rarely offered consistent guidance. It’s no wonder millions of students fall through the cracks each year.

Enter the “Big Blur,” an educational model that aims to erase the dividing line between high school and college by creating new, cost-free institutions that serve sixteen- to twenty-year-old students in grades 11–14. Foundational coursework of eleventh and twelfth grade would be combined with more specific courses and training like those typically offered by community colleges. Work-based learning—including career exploration and on-the-job experience—would be a key feature. And students would have clear, step-by-step guided pathways that lead to postsecondary credentials and associate degrees within specific fields.

Creating and running these new institutions is a tall order, though, and doing it well largely depends on getting four key features right, according to JFF: incentives (in both accountability and finance), alignment, governance, and staffing. There are several well-known initiatives—programs like Pathways to Prosperity, Linked Learning, P-TECH, and New Skills for Youth—that have shown encouraging results. But these initiatives haven’t had a significant impact on the typical student experience. At the time of publication, no state, region, or network that JFF reviewed had successfully combined all these components. So what would it take to do it, and do it well? Here’s a look.

Incentives

For incentives to work, they must be structured to encourage new ways of classifying student learning and support across grades 11–14. Educational institutions must be held accountable for specific outcomes, and funding streams should be flexible enough to be combined with other streams or dedicated as needed.

Alignment

In the current system, the K–12, higher education, and workforce sectors are misaligned. High school and college credits are calculated and tallied differently, class schedules aren’t compatible, and high school and college instructors are trained differently. CTE programs are arguably the farthest along when it comes to aligning and integrating across sectors. For example, regional vocation schools in Massachusetts offer in-demand career education, work-based learning, AP and dual-enrollment courses, and postsecondary certifications. But alignment is more complex in traditional high schools. For the new model to work, students entering eleventh grade should enroll in new institutions offering career pathways that lead to credentials with labor market value by the end of fourteenth grade. Once they’ve graduated, students should have the choice to either enter the workforce or pursue higher education.

Governance

Although state leaders often attempt to foster collaboration across sectors, it’s difficult to do without having similar goals and structures in place. Dual-enrollment systems offer a solid foundation, but many dual-enrollment programs aren’t scaled enough. To effectively design and run institutions that serve students in grades 11–14, a new decision-making body (perhaps similar to the New York Board of Regents) or an empowered senior leader will need to be put in place. To achieve truly unified governance, states will also need to do the following:

Staffing

High school and college instructors go through distinct certification and training processes. High school teachers are trained in both content and pedagogy, and are expected to deliver content and offer student supports. College instructors, on the other hand, typically have graduate-level training in a specific area and are responsible for delivering content but not much else. To effectively teach students in grades 11–14, staff will need to be equipped to teach academic content, facilitate work experiences, and offer student support. One way to accomplish this would be to create a new corps of teachers that specializes in grades 11–14. Another way would be to align and combine teacher qualification and certification systems in a way that allows high school teachers to teach college level material and vice versa. One innovative approach is the University of Texas at Austin’s OnRamps Initiative, which offers dual-enrollment courses to high school students and professional development, like intensive summer training programs, mentoring, and virtual conferences and learning institutes to their instructors.

The paper closes with several action steps. They include crafting campaigns that will help the general public see the benefits of breaking the mold, and providing state leaders with strategies that they can incorporate in their public policy agendas. The authors also call for supporting third-party intermediaries, creating next-generation CTE programs and vocational centers, and establishing learning labs within CTE schools that could help transform traditional public schools.

Source: Nancy Hoffman, Joel Vargas, Kyle Hartung, Lexi Barrett, Erica Cuevas, Felicia Sullivan, Joanna Mawhinney, and Avni Nahar, “The Big Blur: An Argument for Erasing the Boundaries Between High School, College, and Careers—and Creating One New System That Works for Everyone,” JFF (June 2021).

NOTE: Today, members of the Ohio Senate’s Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on Substitute Senate Bill 240 which would authorize mergers of charter schools into a network. Fordham’s vice president for Ohio policy, Chad L. Aldis, gave proponent testimony on the bill. These are his written remarks.

Fordham is a long-time advocate for community—better known as charter—schools. We believe they are an important educational option for parents trying to find the school that will help their children reach their full potential. But we’ve never advocated for choice simply for choice’s sake. We firmly support the principle that charter schools should both serve students well and protect and efficiently use taxpayer dollars.

With that principle in mind, I’m pleased to say that Fordham supports Substitute Senate Bill 240. As you’ve heard in compelling testimony from both Senator Peterson and charter school leaders, allowing for the merger of a group of charters into a network would allow charter schools to operate more efficiently. Specifically, it would make it easier to share staff between buildings, eliminate duplicative reporting requirements, reduce unnecessary meetings, and minimize administrative staff.

All schools should endeavor to operate with these efficiencies, but it’s critical for charter schools. Despite some recent increases in charter school funding, which this body deserves credit for, charters still receive twenty-five percent less taxpayer support per student than traditional public schools. By becoming more efficient and reducing administrative costs, charters will be able to direct more dollars where they belong: into the classroom.

While allowing for more efficiencies, the bill continues to ensure strong accountability measures for charter schools. Here are some of the key provisions that will protect both parents and taxpayers:

Testimony last week raised a question as to whether the charter network would be subject to public meetings requirements. While the bill is drafted in a manner suggesting that charter laws still apply—including open meetings requirements—if there is any doubt I’d recommend this committee add language to ensure that is the case.

In summary, Substitute SB 240 would create an environment making it easier for charter schools to operate more efficiently without sacrificing accountability. For those reasons, we are pleased to support this legislation.