The good, bad, and ugly of the House budget

The Ohio House recently passed its version of the state budget (HB 110) for FYs 2022–23.

The Ohio House recently passed its version of the state budget (HB 110) for FYs 2022–23.

The Ohio House recently passed its version of the state budget (HB 110) for FYs 2022–23. The headline for K–12 education was the inclusion of the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan into its budget bill (as most observers expected). If enacted, this proposal would overhaul Ohio’s school funding formula and—when fully implemented—add an additional $2 billion per year in state outlays for K–12 education. Beyond the headline, the House budget contains a slew of policy details—including a couple small steps forward, a few head-scratchers, and some bad ideas, too.

Baby steps forward

Creates a “direct funding” model for choice options. In line with the original Cupp-Patterson plan, the House budget moves public charter and STEM schools along with private-school vouchers to a direct funding model. Although this shift doesn’t affect the funding levels for choice students, the transition could alleviate tensions around the current “pass through” approach whereby money designated for these students is subtracted from their home districts’ state aid. Direct funding, however, needs to be done with extreme care to insulate choice programs from future budget reductions or even line-item vetoes. On this count, HB 110 isn’t quite there. The income-based EdChoice program is listed as a standalone item, making it vulnerable to cuts in the future. Charters, STEM schools, and the other voucher programs are funded via the main education appropriation, but these options could still be exposed to a line-item veto under HB 110. Though unlikely to occur under Governor DeWine, choice programs could be targeted in future budgets if the House approach to direct funding is adopted.

Eliminates a proposed 10 percent reduction to charter and STEM schools’ base cost. For no apparent reason, an earlier iteration of the Cupp-Patterson plan calculated charter and STEM schools’ base costs at lower levels than districts. Fortunately, HB 110 corrects this glaring inequity by eliminating this reduction. However, HB 110 retains another inequitable policy within the proposed funding framework that denies charters and STEMs a minimum number of special teachers (e.g., art or physical education) and student support staff. The absence of these minimums—which apply for districts—decreases funding for charter and STEM schools by hundreds of dollars per pupil, again with no clear policy rationale.

The head-scratchers

Increases economically disadvantaged funding but at the expense of the Student Wellness program. From the outset, the Cupp-Patterson plan has called for an increase in the “categorical” funding stream based on economically disadvantaged (ED) enrollments. That’s a good thing, and HB 110 incorporates this increase. But the legislation finances it by using dollars budgeted for the Student Wellness and Success Fund (SWSF), a new-ish program championed by Governor DeWine that aims to support students’ social-emotional and mental health needs. The House explained the decision by saying that it streamlines duplicative programs. There is some truth to that, as both programs generally direct more money to high-poverty schools. Still, the move is puzzling. It was always expected that the increase in ED funding was going to improve the equity of the system because the Cupp-Patterson plan never proposed raiding another “progressively” structured funding stream to pay for it. But the way HB 110 funds the ED increase seems to simply maintain the status quo, robbing Peter to pay Paul. How does that help low-income kids?

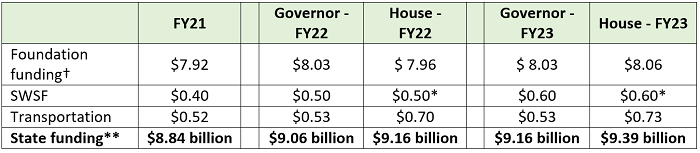

Leaves tough decisions about fully funding the Cupp-Patterson plan to future leaders. Given all the excitement about the funding bump proposed in the Cupp-Patterson plan, the House budget calls for generally modest increases in education spending. Table 1 displays education funding in the current year (FY 2021) and the amounts proposed by Governor DeWine and the House for the next biennium. Relative to the Governor’s plan, the House raises state education funding by roughly $100 million in FY 2022 and $230 million in FY 2023.

Table 1: An overview of state education funding, current and proposed (in billions)

*In the House plan, the Student Wellness and Success Funds remain a standalone line item, but are used primarily to fund an increase in the economically-disadvantaged component of the funding formula. **This excludes federal and local dollars, various smaller state expenditures (e.g., educator licensing and assessments), and money for K–12 education not funded via ODE budget (e.g., school construction dollars and property tax reimbursements). † This includes the additional $115 million that was included in the omnibus amendment to the House budget.

The reason why the House funding increases fall short of the promised $2 billion in added spending is due to HB 110’s six-year phase-in of the Cupp-Patterson plan. While this gradual approach may have been necessary given budget constraints and was part of a legislative version introduced in the last General Assembly, it continues to raise questions about how the rest of the plan will be paid for, especially now that the House has soaked up the SWSF funding. Are they leaving the heavy lifting—possibly raising taxes—to future lawmakers? Will they decline to fund it or choose to start over? In the end, it remains a mystery why House lawmakers would champion an education funding plan without offering a concrete roadmap for covering its costs.

Steps backward

Cuts funding for the quality charter schools program. Back in 2019, Ohio enacted a first-of-its-kind program that provides much-needed extra funding for high-performing charter schools. These supplemental funds help to narrow chronic funding gaps, build the capacity of successful schools to serve more kids, and incentivize continued improvement in sector performance. In the first two years of the program, about a quarter of Ohio charters received these funds. However, as more schools qualified in year two, the per-pupil funding amounts dropped to fit the program’s fixed appropriation. Rather than receiving the full $1,750 per economically disadvantaged student, qualifying schools received just $1,023. To better align the funding amounts, Governor DeWine proposed increasing the program appropriation to $54 million per year. Unfortunately, the House cut that amount to $30 million. Unless the Senate reverses course, this will underfund the program and deny high-performing charters critical resources needed to serve more students.

Slashes funding for interdistrict open enrollment. More than 80,000 Ohio students attend school in a neighboring district through the state’s interdistrict open enrollment program. Under current policy, the state funds these students at the full “base amount” of $6,020 per pupil. But as discussed in more detail here, the Cupp-Patterson plan drastically reduces these per-pupil amounts for open enrollees. Unfortunately, HB 110 does not address this problem. If the plan is enacted without a fix, thousands of open enrollees may find themselves shut out of the schools they currently attend, as districts decide that it no longer makes economic sense to enroll non-resident students.

Allows opt-outs of college-entrance exams. The last glaring problem with HB 110 is its introduction of an opt-out provision to the universal administration of ACT or SAT exams to high school juniors. Starting with the class of 2018, this policy has ensured that all young people have at least one opportunity to take these assessments. Previously, less than half of many districts’ graduates took these exams. In Lorain, for example, just 16 percent of its classes of 2016 and 2017 took the ACT or SAT. In Lima, it was a mere 36 percent. How many students who skipped these tests could’ve gone on to competitive colleges? We’ll never know because—at that time—no one required them to take an entrance exam. Sadly, the House makes a change that could reduce the number of students taking college-entrance exams and inadvertently close doors to higher education for some talented young Ohioans.

* * *

K–12 education policy should focus on unlocking great educational opportunities for all Ohio students. Overall, it’s difficult to see how the House budget furthers that goal. The chamber’s signature school funding plan is left dangling in the wind. Charter schools—even the best ones in the state—will continue to suffer from inequitable funding. Interdistrict open enrollment will be gutted. Even funding for low-income students is barely improved, if at all, under HB 110. Thankfully, the House isn’t the last stop. With any luck, the upper chamber will take a different approach, one that puts Ohio students at the heart of education policy.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

Favoritism. Unfairness. Inequity. Even the most generous interpretation of these words would carry negative connotations. Generally, it’s not good when one sibling is favored over another.

But this is exactly what Ohio’s funding currently does–students who attend certain types of public schools benefit more than students who attend other types of public schools. “Surely not!” you may say. “Why would Ohio ever favor some public-school students over others? Are some public school students worth less than others? That’s not fair.” You’re right. That would not be fair, and it would be a serious allegation that requires clear evidence of inequitable treatment.

Today, ExcelinEd is releasing evidence that indicates the state of Ohio values some public school students more than others. In fact, this report finds an overall funding gap of $121.2 million, or about $1,452 per student. It’s a specific gap related to facilities–a need for which only 18.1 percent is met by Ohio’s existing policies. Stated a bit differently, if this gap were closed, then the average charter school could hire an additional seven teachers, or it could give current classroom teachers a 39 percent raise. The state’s traditional school districts, on the other hand, have received tens of billions in state funding for school construction on top of the local tax revenue they generate to support facility needs.

This facility gap comes on top of a large disparity in the funding Ohio’s charter schools face in meeting their regular operational needs. In other words, to meet facility needs, charter schools must dip significantly into operating funds, which are already much lower than those received by traditional public schools.

More than 83,000 students attend brick and mortar charter schools in Ohio. More than 8 in 10 of those students are economically disadvantaged, and 2 of 3 identify as students of color. Also, 94 percent of these schools are located in urban areas where the cost of facilities can be high and options scarce. But charter schools don’t have the ability to levy taxes or issue bonds–only traditional public schools can do that. That means charter schools heavily rely on state policy and state funding for facilities.

It does not have to be this way. ExcelinEd has released a report and tool that can serve as a resource to policymakers as they make decisions that will balance the needs of charter school students and the potential cost to the state.

In some cases, pulling a certain policy lever may impose minimal to the state but have a large positive impact for charter schools. For example, if the state were to pass legislation that required districts to share bond revenues with public charter schools based on the proportion of students attending, then that one policy change would mean 82 percent of charter facility needs are met rather than 18.1 percent.

But that is not the only policy lever that can be pulled. Another lever would allow charter schools to access under-used district buildings at no or low cost. If one-third of charter schools were able to take advantage of a policy like this in Ohio, then the amount of need met by the state would nearly double from 18.1 percent to about 38.8 percent. This Charter School Facility Index Tool outlines 7 levers that can be used to increase the fairness and equity of Ohio’s state funding. It’s designed so that policymakers and other stakeholders can plug and play.

Just because things are unfair now, doesn’t mean they have to stay that way. We hope this report and tool will be a resource for state leaders as they aim to expand opportunities for every young Buckeye in the state.

This piece was originally posted on the blog of ExcelinEd.

Over the past year, media outlets have covered an impending lawsuit against Ohio’s EdChoice program. The Ohio Coalition for Adequacy & Equity of School Funding—an organization financed by school districts—is leading the effort to strike down the state’s largest private school scholarship program. Although the suit has not yet been filed, it will likely claim that EdChoice violates the Ohio Constitution’s call for “a thorough and efficient system of common schools throughout the state.”

For many in Ohio, a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of a school choice program might feel like Groundhog Day. Ohio’s first private-school voucher law, the Cleveland Scholarship and Tutoring Program, was challenged by the teachers’ unions and other interest groups on first amendment grounds almost immediately after it began in 1997. After much wrangling in the lower courts, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the program in the landmark Zelman v. Simmons-Harris decision in 2002.

At about the same time as the Zelman litigation, a similar coalition of anti-parent-choice groups sought to overturn the state’s recently enacted charter school law. In that case, the plaintiffs focused on the Ohio Constitution, claiming that charters offend the “common school” system and deprive traditional districts of funding. In its 2006 decision, Ohio Congress of Parents and Teachers v. State Board of Education, the Ohio Supreme Court rejected these arguments and upheld the charter school law.

Although charters and private-school scholarships are distinct forms of school choice, the forthcoming EdChoice lawsuit will probably raise legal issues similar to Ohio Congress. As such, it’s worth a review of the main arguments put forward by the plaintiffs in that case and the response of the court.

The “common schools” argument

One of main ideas behind charter schools is to give educators more flexibility to experiment with different educational approaches, while holding them accountable for student outcomes. The plaintiffs in Ohio Congress argued that charters’ alternative governing structures violated the “common schools” clause in the Ohio Constitution. The Supreme Court acknowledged the differences between charters and traditional districts, but ruled that they did not create a constitutional violation. The court wrote:

To achieve the goal of improving and customizing public education programs, the General Assembly has augmented the state’s public school system with public community schools.... Requiring community schools to be operated just like traditional district schools would extinguish the experimental spirit behind R.C. Chapter 3314 [charter school law].

It then concluded:

In providing for community schools within that system [of common schools], the state legislature has not exceeded its powers.

The plaintiffs in the EdChoice lawsuit may very well play the “common schools” card again, this time arguing that the state cannot support nonpublic schools. The courts, however, should remember that—in line with Ohio Congress—the state’s Constitution does not limit the legislature’s authority to supporting traditional districts alone. To be sure, legislators must create, at a baseline, a common school system. But this doesn’t mean that Ohio is confined to a singular, one-sized-fits-all system. The General Assembly can—and should—permit and support a wide range of educational options that better meet the varying individual needs of Ohio’s almost 2 million students.

School funding arguments

A related argument from Ohio Congress that is almost sure to remerge in the EdChoice lawsuit is that choice options deprive districts of funding, thus creating a less “thorough and efficient” system. However, contrary to this claim, per-pupil funding has actually increased in districts where charters and private-school choice have been most prevalent. The courts should certainly review these data, but they should also consider the high court’s response in Ohio Congress to the allegations that charters unconstitutionally drain money from districts.

First, the court rejected claims that the legislature cannot reduce state funding to districts when children transfer to charter schools because such a policy might increase the reliance on local taxes. It wrote:

Nothing in the Constitution, however, prohibits the General Assembly from reducing funding because a school district’s enrollment decreases. If a child moves out of the district altogether, the state is permitted to reduce its funding to that child’s district because state money follows the child. For example, if a child leaves a school district to attend private school, or to be schooled at home, the state is required to reduce its funding to that district. The same thing occurs when a child opts to attend a community school.

Second, the plaintiffs further asserted that charter schools were being funded by local taxes—an argument also commonly heard in the EdChoice debates. The Ohio Supreme Court dismissed this claim, as well:

A change in the number of students does not affect the amount of the school district’s local share, because local tax dollars are contributed by the district’s taxpayers and do not depend upon the number of students attending the school. The full amount of the local tax money will continue to be available to the local school district. In other words, state funds follow the student; local funds do not.

School funding debates have long been rife with misconceptions. Fortunately, the Ohio Supreme Court carefully sifted fact from fiction. Yes, it’s entirely appropriate for the legislature to reduce state funding when children exit a school district for whatever reason. No, local funds do not follow students to charter schools—something that also applies in the case of EdChoice scholarships. With any luck, the courts will continue to apply a proper understanding of the state’s funding system in the EdChoice lawsuit.

***

The forthcoming case is sure to wade into legal semantics. The details are important, of course. But sadly, these anti-choice lawsuits fundamentally seek to undermine tens of thousands of poor and working class parents’ right to choose schools that best meet their kids’ needs. As the Ohio courts—once again—scrutinize one of the state’s school choice programs, they should remember most of all the deeper truth expressed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1925 landmark decision, Pierce v. Society of Sisters:

The child is not the mere creature of the state; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.

In the end, parents—not the “system”—have the ultimate right and responsibility to nurture the next generation of Ohioans. Rather than decrying policies such as EdChoice as “unconstitutional,” we should all begin to see them as a way of empowering Ohio parents to direct the destiny of the children they are tasked with raising.

Problem solving involves a complex set of mental steps, even when it happens quickly. A group of researchers from the University of Virginia sought to test one specific aspect of the process—the types of solutions people consider—and uncovered what could be an important human attribute, with significant implications for public policy.

They were interested in determining whether problem solvers have a tendency to opt for additive or subtractive solutions. That is, when faced with a problem that requires the transformation of an object, idea, or situation—say, a change to a recipe—how often do people add components (ingredients or steps, perhaps, if it’s a recipe) versus take them away?

The researchers conducted eight separate experiments, three in person and the rest virtually. Approximately 200 to 300 people participated in each for a total n-size of 1,585. Examples of experiments include modifying a Lego structure to support a brick, when adding pieces cost money and removing pieces is free; improving the design of a mini-golf hole, where multiple changes are allowed and recorded; and fixing a multi-colored asymmetrical digital grid pattern to be perfectly symmetrical by changing block colors, in which the only correct option was a subtractive one.

The bottom line is that no matter the problem at hand or the incentives provided, people tend to default to additive transformations and, in doing so, completely overlook subtractive options. For example, in the digital grid experiment, only 20 percent of participants favored subtracting blocks even though that was the only successful option. In another experiment, just 11 percent of improvement suggestions offered to an incoming university president via anonymous drop box were subtractive in nature. Across the board, participants choosing a subtractive transformation in an experiment never cracked 40 percent. In fact, most experiments were closer to 25 percent.

Participants did offer a greater number of subtractive solutions when they were given specific instructions to consider taking something away, when such options were made obvious (“Improve this grilled cheese and chocolate sandwich”), and when they were provided with several opportunities to propose solutions such as with the mini-golf example. But the researchers note that the need for such conditions underscores the human predisposition toward additive options.

The study concludes by saying that this bias toward addition—where “more” automatically equals “better”—could explain certain aspects of societal ills such as overburdened schedules, institutional red tape, and damaging effects on the planet. In a Washington Post analysis of the study, one of the researchers points to legislation and public policy as other areas where less might be more. In the realm of education, there is a tendency toward making teaching and the running of schools more complex over time, not less. We are forever adding new initiatives—putting new problems to solve on teachers’ plates while never taking anything off. If only decisionmakers could see and embrace “addition by subtraction,” new and better solutions may be more likely to emerge.

SOURCE: Gabrielle S. Adams, Benjamin A. Converse, Andrew H. Hales, and Leidy E. Klotz, “People systematically overlook subtractive changes,” Nature (April 2021).

A new report from the Journal of Chemical Education takes a look—pre-pandemic—at the ways in which college students benefited from a new opportunity to participate remotely in their education.

In this study, college juniors taking a core course in chemical engineering at the University of Michigan were required to complete a nine-week team-based project on the topic of mass and heat transfer. They had to identify a relevant problem they wanted to tackle, develop a solution via experimentation, and then present their findings in various forms both written and visual to an audience. Traditionally, the visual presentation consisted of an in-person replication of the team’s experiment in front of the class. But in 2017, an option was added for students to create a video presentation instead.

The researchers used this change to test whether the video presentation option had an effect on students’ engaged-learning outcomes. Specifically, the analysts were looking to see the effect of the presentation modality on students’ perceptions of their creativity, innovation and risk taking, social responsibility (for addressing social and ethical issues and for public outreach), teamwork, confidence in their ability to apply engineering concepts and to tackle future challenges, and communication for written and oral presentations.

A total of 248 students completed the course project in the fall semesters of 2017 and 2018, with 137 choosing an in-person presentation and 111 choosing to create a video. Multiple surveys and focus groups were conducted with participants throughout the semester, including a pre-project questionnaire to obtain baseline data. Slightly less than 60 percent of students reported ever creating a similar video presentation before, but the students’ reported comfort score was nearly identical for both video and in-person presentations, indicating a familiarity with non-academic presentations such as YouTube videos or Vines.

A post-project survey showed that students who created a video presentation experienced significantly greater impact on their perceived creativity (mean score: 8.9/10) as compared to those who delivered an in-person presentation (mean score: 7.7/10). This is consistent with the pre-project survey findings. Similarly, video creators reported experiencing a higher impact on risk taking (mean score: 7.7/10) compared to their in-person peers (mean score: 6.1/10), as the pre-project data suggested.

As an example of this, the researchers cite focus group data which specifically noted the time constraints on the in-person presentation. A handful of students reported creatively condensing their in-person presentations, but a majority responding said they chose shorter options that could be completed within the 10 to 15 minutes allotted, thus limiting their choice of problem and solution. By contrast, a majority of students opting to create a video reported conducting experiments that took far longer than 15 minutes to complete, editing hours or even days of data/footage into short and illustrative bites.

The impact of the presentation modality on teamwork, self-confidence, and communication was not significant, perhaps indicating that these learning outcome areas were more strongly influenced by the research phases of the project—which were largely similar regardless of ultimate presentation type.

The upshot is that video presentations built on the strengths of the other aspects of the project and helped students in this class be more creative and take more risks in pursuit of their education. However, video creators reported a much lower impact on social responsibility than their in-person peers, entirely attributed to the lack of in-person communication with the audience. In-person presenters reported that a live Q & A session boosted understanding of the subject matter for both the audience and themselves, while video creators received feedback only from their instructors and reported no additional a lack of engagement beyond the completion of the work itself.

Over the last year, pandemic-related disruptions of traditional education models have led to a greater reliance on digital teaching and learning in both K–12 and higher education. While the preference of many is to return to a fully in-person model, some students and teachers managed to adapt quite well to various aspects of the virtual and hybrid models. Live, synchronous interaction is important, but we have evidence that subject matter knowledge, individual and group creativity, and personal self-confidence can also be boosted by thoughtful and well-designed remote learning experiences as well.

SOURCE: Andrew J. Zak, Luke F. Bugada, Xiao Yin Ma, and Fei Wen, “Virtual versus In-Person Presentation as a Project Deliverable Differentially Impacts Student Engaged-Learning Outcomes in a Chemical Engineering Core Course,” Journal of Chemical Education (March 2021).

Historically, children have been assigned to public schools based on their home address. For some students, this works out fine. But for many others, geographic assignment locks them into schools that don’t meet their needs. What can be done to break the link between students’ zip codes and their school?

The Buckeye Institute and Fordham Institute invite you to a forthcoming event where we’ll hear from Tim DeRoche, author of A Fine Line: How most American kids are kept out of the best public schools. This book offers an eye-opening account of how families are denied access to desirable schools through the educational equivalent of “redlining.” Following Tim’s presentation, we’ll discuss national and local efforts to open doors for students who have traditionally lacked access to great schools. Audience questions will also be taken.

NOTE: Today, the House Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on HB 200, one of several legislative efforts underway to revamp Ohio’s school and district report cards. Fordham’s Chad Aldis presented opponent testimony to the bill. These are his written remarks.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

While I stand before you to provide opponent testimony, I’d like to begin my commending you and the bill sponsors for tackling an important and incredibly complex issue. School and district report cards perform a variety of critical functions. For parents, the report cards offer objective information as they search for schools that can help their children grow academically. For citizens, they remain an important check on whether their schools are thriving and contributing to the well-being of their community. For governing authorities, such as school boards and charter sponsors, the report card shines a light on the strengths and weaknesses of the schools they are responsible for overseeing. And, finally, as we are reminded during challenging times like this, it can help officials identify schools in need of extra help and resources.

Because of the many roles it plays, it’s essential that Ohio get it right when designing a report card. The current report card has some important strengths and has even drawn national praise from the Data Quality Campaign and the Education Commission of the States. Nevertheless, there are facets of the report card that can and should be improved. Fordham published a report in 2017, Back to the Basics, calling for a variety of reforms to Ohio’s report card framework including simplifying it and making it fairer to schools serving high percentages of economically disadvantaged students.

And yet, you’re probably wondering why this is opponent testimony. We strongly believe that any report card must adhere to four critical principles. First, it must support equity and ensure high expectations for all students and that each student counts. Second, it must advance transparency and offer parents and communities clear, simple, honest information about school performance. Third, it should be fair and give every school the opportunity to demonstrate growth and improvement. And, fourth, it must be accurate and ensure components are measuring what is intended.

In analyzing HB 200 against these principles, we have serious concerns. For ease of consideration and discussion, this testimony will attempt to be specific and identify issues one at a time.

Report cards are a balancing act. Ohio’s current state report card can and should be improved, but it’s critical that any changes ensure that the report card supports equity, transparency, fairness, and accuracy. As introduced, HB 200 falls short—especially in regards to equity and transparency. We urge this committee to continue its efforts to ensure that the report card is consistent with our state’s priorities and beliefs. Namely, that all students—given the proper support—can learn and achieve at high levels.

Thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony.