Good education policy can come from all quarters

Last week, the Plain Dealer published a guest commentary about the current state of education policymaking in Ohio.

Last week, the Plain Dealer published a guest commentary about the current state of education policymaking in Ohio.

Last week, the Plain Dealer published a guest commentary about the current state of education policymaking in Ohio. Its authors, Joel Malin and Kathleen Knight-Abowitz, took aim at “poorly conceived voucher and school accountability policies” and complained that private interests are wrongly shaping education in the Buckeye State.

It’s passionately argued. Unfortunately, the majority of its arguments are incomplete or misinformed.

The authors’ primary target is Ohio’s largest private-school voucher program, EdChoice. Their focus is understandable, since EdChoice has been the center of contentious debate in the last few weeks. But their assessment of the program isn’t quite accurate. For example, they refer to EdChoice, which was established way back in 2005 and currently serves over 30,000 students, as an “experiment.” That’s a misleading characterization. EdChoice is not a fly-by-night operation. It’s been part of Ohio’s school choice landscape for over a decade, and vouchers have been available in Ohio in some form since 1997.

They claim the perspectives of communities, parents, and students are “being given short shrift.” But to make such an argument completely ignores the hundreds of educators, parents, and students who contacted legislators or provided testimony over the past few weeks to voice their impassioned support for EdChoice and the opportunities it unlocks.

The commentary also makes passing reference to a “rigorous study” that uncovers negative impacts of EdChoice. Fordham proudly commissioned this study, which was carried out by well-respected economist David Figlio of Northwestern University. It is true that his analysis found some disappointing results for some of the earliest EdChoice recipients. But the op-ed contributors omit two critical facts. First, for methodological reasons, the study only analyzes a small segment of EdChoice participants (445 students). It’s impossible to know what the program’s effect would have been had all students been included. Second and more importantly, the op-ed writers neglect the positive effects EdChoice has on public school students. It’s easy to speculate as to why they ignore this key finding, given the incessant complaint voucher opponents make that EdChoice damages public education.

The authors’ questions about the EdChoice eligibility list also show a slightly superficial understanding of Ohio’s recent education policy history. They wonder, for instance, how such a “dramatic increase” in voucher eligibility occurred, and question why schools were judged based on student scores from 2013 and 2014 but not 2015–17. The primary answer to these questions is safe harbor, a policy that was enacted back in 2015 as a means of shielding schools from sanctions during Ohio’s transition to new assessments. These provisions prohibited the state from doing two things: using test scores from 2014–15, 2015–16, and 2016–17 in any type of accountability decision, including the designation of EdChoice eligible schools; and incorporating performance eligibility changes related to value-added progress and K–3 literacy grades, which had been made in 2014 and the years prior. It’s also worth noting that district leaders, school administrators, and teachers were some of the loudest voices advocating for adoption of a safe-harbor policy—the very same groups the authors argue are being “regularly ignored” by lawmakers.

To bolster their claims that the wrong voices are being heeded by lawmakers, the op-ed targets another much-debated education policy: graduation requirements. The subject of their ire is Ohio Excels, a nonprofit organization that facilitates business engagement in education. To their credit, they note that it’s appropriate for business groups to wield some influence in education policy, as they have an interest in making sure that Ohio schools are preparing students for the workplace.

So then what’s the problem? According to the authors, Ohio Excels was a “major player” in crafting the recent changes to graduation requirements. They imply that lawmakers were forced to “choose sides” between business leaders and educators, and that the business community was given a “tremendous amount of deference.”

It’s true that Ohio Excels was a major player in the development of the new requirements. But it wasn’t the only player. In fact, one of the other chief architects of these standards was the Alliance for High Quality Education, a group representing more than seventy Ohio school districts. These districts represented the interests of the very same professional educators the authors believe should be influencing policy. To imply that business leaders hijacked the process and were solely responsible for the new standards is wrong.

The authors also seem to take issue with the fact that the plan backed by Ohio Excels—and all those school districts—was not the same plan backed by the state board of education. Apparently lawmakers should have heeded the state board solely because the board’s role is to “help advise education policy creation.”

But that’s not how policymaking should work. A good education policy is one that puts students and their long-term interests first. In this case, a good argument can be made that the state board’s plan didn’t do that. It championed alternative assessments that lacked objectivity, comparability, and reliability. It also included measures that were burdensome for local districts, easily gameable, and of questionable rigor. Ignoring these serious flaws and choosing to be blindly deferential to the board of education would have been irresponsible.

In a final attempt to criticize policymakers, the authors briefly mention a few other states that have been subjected to the influence of “for-profit, pro-business, and private education providers.” They identify two in particular—Florida and Indiana. Interestingly, Florida and Indiana are two of a handful of states that have shown strong gains on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the “Nation’s Report Card,” over the last two decades. Florida, in particular, has fared extremely well, registering strong gains, especially among its low-income and minority students.

Citing states where student performance has improved dramatically, especially for kids of color and low-income students, as evidence of the dangers of private interests is a bit of a headscratcher. So is using the term “pro-business” as a critique. Massachusetts, the highest performing state in the country, pulled off its “Massachusetts miracle” by striking a grand bargain between policymakers, K–12 stakeholders, and—you guessed it—business leaders. Delaware, which is home to an innovative, statewide career-and-technical-education program called Pathways, is making great strides for kids because of strong public-private partnerships. If Ohio really wanted to improve outcomes for students, it would try harder to emulate states like Massachusetts, Delaware, and—yes—Florida and Indiana.

At the end of the day, where a policy comes from—whether it’s Ohio’s school districts, choice advocates, businesses, or the parents and students that are served by our school systems—shouldn’t be the deciding factor of its merit. What should matter most is whether the policy is in the best interest of kids.

“Education is not one-size-fits-all” is a common phrase heard in today’s education debates. There’s a good bit of truth to the mantra. Every child is unique in his or her own way, and policies and practices should reflect those differences. To its credit, Ohio acknowledges the importance of tailoring education to the needs of individual students. As suggested in the title Each Child, Our Future, the state’s strategic plan—developed with the help of thousands of Ohioans—focuses on customization, and it claims to “advance shifts in education policy and practice” that include “honoring each student” and “emphasizing options.”

These guiding principles, however, seem to have been forgotten in the raging debate over EdChoice, Ohio’s main private-school scholarship (i.e., “voucher”) program. Instead of centering the debate on the needs of each family and child, it has mostly focused on the perceived harm to school districts. That dubious claim, flogged incessantly by voucher critics, is contradicted by research showing just the opposite—that the competition associated with private-school choice actually improves public schools.

But I digress.

So, how does EdChoice align with greater customization in K–12 education? Let’s consider that question through the lens of the two key shifts mentioned in the state’s strategic plan.

Honoring each student

As I’ve said in media comments, most Ohio families are likely quite satisfied with their local school district. That assumption is based on survey data showing that a solid majority of parents view their local schools positively, in addition to the longstanding custom of parents selecting their school system via the real-estate market. But this doesn’t mean that the district is the best option for all children. Consider just a few reasons why it may not be.

When parents and students find themselves in situations such as these, it’s hard to say that their assigned school is fully honoring them. To be clear, this isn’t a criticism of the traditional education system. It’s just naïve to expect public schools, even at their very finest, to be all things to all people (and that’s true for non-publics, as well). What all this suggests is that Ohio should be encouraging a wider range of school options, not choking them off. That leads us to the next section.

Emphasizing options

A choice-rich system of schools enables more parents and students to match their needs with the offerings of different educational providers. After decades of policy reform, many Ohioans have tuition-free, public-school options at their fingertips. They include alternatives accessible via inter- and intra-district open enrollment, STEM and charter schools, and career-technical centers. Private schools, of course, are also an option. But unfortunately, tuition costs often restrict access to only the wealthy.

That’s where the EdChoice scholarship comes in. Since 2006–07, Ohio has provided state assistance that unlocks private-school opportunities for low- to middle-income families. Today, more than 40,000 students use an EdChoice voucher, some of whom have voiced strong support for the program in recent days. At one committee hearing (starting at 12:45 in the video), a Corryville Catholic student testified, “Without EdChoice, it would be a huge struggle to pay the extra tuition. EdChoice makes it possible for many of us to get into Catholic high schools.”

These hearings were held as the state legislature continues to wrestle with policies that would expand EdChoice eligibility from its somewhat limited base to more Ohio households. The impasse between the Senate and House has largely revolved around the program’s controversial eligibility rules for the performance-based EdChoice voucher, which is slated to expand significantly this fall. Although both chambers have sought to scale back that expansion (though to a very different extent), they appear to have agreed that the income-based scholarship should be accessible to more working families. The Senate has proposed to increase the income-eligibility threshold from 200 percent to 300 percent of the federal poverty guideline (FPG), while the House has suggested moving to 250 percent.

Although it cannot exhaustively cover all “needy” students (as described above), expanding choice via the income-based program is likely more politically manageable. Even so, some have suggested that relaxing the income thresholds as currently proposed might be too generous. But when looking at private-school options from the perspective of middle-income families, that’s not the case. Consider a four-person household with an income at 300 percent FPG, or $78,600 per year. After paying federal, state, and local taxes—EdChoice uses pre-tax incomes—that family likely has somewhere around $60,000 in disposable income. After paying the costs of housing—the average yearly mortgage payment is about $12,000—utilities, transportation, food (for four), healthcare, and saving for retirement and college...well, you get the picture. Without EdChoice, most hard-working, middle-income Ohioans will have difficulty affording private-school tuition, even at a modestly priced school. Through scholarship support, however, Ohio would emphasize options by opening doors to more schools for families such as these.

***

For the past decade and a half, the EdChoice program has played an integral role in supporting students who need something different from their educational experience. By providing much-needed financial aid, it puts more private-school options within their reach. However accomplished, continuing to expand EdChoice would further advance the state’s goal of customizing education for each individual child.

In the last few years, a significant number of states have set attainment goals in an attempt to increase the number of adults with a postsecondary certificate, credential, or degree. The ambitious nature of these goals has required leaders to look beyond traditional high-school-to-college routes and invest more purposefully in career-and-technical-education (CTE) programs, which teach students both academic and technical skills.

Achieving these lofty goals, however, requires thoughtful policies and rigorous implementation. Delaware offers a great example of how to do so. Back in 2015, a diverse group of stakeholders—including the governor, state agencies like the departments of education and labor, business leaders, K–12 and higher education representatives, and philanthropic organizations—joined forces to launch Pathways, a statewide program that offers K–12 students the opportunity to complete a program of study aligned with an in-demand career before they graduate. Pathways is officially part of a Jobs for the Future network called Pathways to Prosperity, which includes similar programs in fifteen other states. One of those states is Ohio, though its involvement is only at a regional level.

Here’s how Delaware’s program works: Each pathway is a program of study that involves a sequence of specialized courses, a work-based learning (WBL) experience, and the option to earn college credit. For example, the manufacturing engineering technology pathway requires students to complete three specially designed courses and a WBL experience, and permits them to earn up to three college credits. Other pathways, like computer science, require students to take AP courses aligned to the subject matter. Informational sheets for the twenty-five designated pathways are available online. They include potential jobs and projected salaries for three levels of attainment: a certificate, an associate degree, and a bachelor’s degree. The Pathways website also offers career exploration tools that allow students to explore labor market data and in-demand occupations.

Because it’s a CTE initiative, work-based learning is an integral part of Pathways. Depending on a student’s age and program of study, such experiences could mean job shadowing, co-ops, or an apprenticeship. The NAF Academy of Finance pathway, for instance, includes a 120-hour paid summer internship. Some programs of study also prepare students to earn credentials upon completion. For example, the Architectural Engineering Technology pathway prepares students to earn AutoCAD and Revit certification and up to ten college credits.

This school year, Delaware’s Pathways program is serving approximately 15,000 students. State leaders have a goal of serving 20,000 students—or half the state’s public high school population—by 2020–21. There are forty-two participating high schools, a number that includes all nineteen of the state’s public districts (both comprehensive and vocational-technical), eight charter schools, and two schools for at-risk students.

The first students to complete the program received diplomas in 2019, so it’s too soon to know whether Pathways has positively impacted their long-term outcomes. But a recent report pointed out just how many stakeholders could benefit if this initiative lives up to its potential. For schools, the program could increase student engagement by making learning more relevant and interesting. For students, it offers the opportunity to earn an industry-recognized credential, work experience, and college credit while working toward a high school diploma. Businesses get access to a pipeline of new employees and have the opportunity to shape the training and curricula in their fields. And for the state as a whole, the program could contribute to meeting employer’s talent demands, attracting new businesses, improving the economy, and increasing the likelihood of meeting the attainment goal.

Some of these stakeholder groups are already seeing benefits. According to a baseline report published last year, 85 percent of surveyed employers reported they were likely or very likely to hire a student they had employed during an immersive work-based learning experience—a promising development for young people and businesses alike. Since January 2019, more than 240 employers in over twenty industries have expressed interest in working with schools. And although one of the greatest roadblocks to CTE expansion is parental awareness and support, approximately 60 percent of parents reported that they would recommend CTE pathways to their family and friends.

Overall, Delaware’s Pathways program is a promising plan to invest in students, local businesses, and the state’s future. It’s a win-win for everyone involved. Most significantly, though, it ensures that the most important stakeholders—students—are leaving the K–12 sector not only with knowledge and skills, but also valuable work experience and even workplace credentials and college credit.

Given all its potential, it’s worth asking whether Ohio could implement a similar program and reap some of the same rewards. Stay tuned for a future piece that will examine that possibility.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

“Gap closing” is one of Ohio’s six major school report card components. The ostensible purpose of the component is to provide the public with information on which schools are making progress in closing achievement gaps among Ohio’s most disadvantaged students. Gap closing, however, has long been criticized on multiple fronts: it does not actually measure the closing of achievement gaps; it is highly correlated with socioeconomic status; and biases Ohio’s accountability system toward rewarding achievement rather than growth. To these woes we can add another concern, those centered around gap closing’s newest sub-component: English language progress (ELP).

Traditionally, Ohio’s gap closing measure has assessed schools on how various subgroups—including those who are African American, Hispanic, or economically disadvantaged, or have special needs—perform in three areas: English language arts, math, and graduation rates. With the addition of ELP to gap closing in 2017–18, Ohio schools with English learner (EL) populations are now additionally evaluated based on those students’ performance on the Ohio English Language Proficiency Exam, an alternative assessment given to ELs.

The inclusion of ELs into the report card is required under federal law and shines a much-needed spotlight on the academic needs of one of the state’s fastest growing student populations. But while well-intentioned, the new ELP measure is imperfectly implemented. This post highlights three chief shortcomings.

First, the ELP measure relies on raw proficiency thresholds. Proficiency thresholds only give schools credit for students who achieve proficiency in a content area; no credit is assigned for moving students closer to proficiency. Second, the ELP measure effectively imposes all-or-nothing point thresholds on schools. Of the 780 schools that have been assessed on the measure since 2018, some 73 percent received the full 100 points, while another 25 percent received 0 points. Only 2 percent of assessed schools received partial points for the ELP sub-component. Finally, the contribution of ELP to the overall gap closing score and report card grades varies dramatically across schools, and for some schools weighs very heavily.

Taken together, these features add up to a system in which the performance of very small numbers of students can have disproportionately large effects, not only on a school’s ELP sub-component grade, but also on the entire report card grade. Importantly, the inclusion of ELP may benefit some schools, “inflating” their final report card score, while penalizing others. In this post, however, I focus on ELP’s potentially negative consequences because the point penalties imposed on schools are, on average, about three times as large as any potential bonuses.

Let’s take a closer look at how the various pieces of ELP fit together.

The use of raw proficiency thresholds and the largely all-or-nothing allocation of points are related, and they contribute to small numbers of students having potentially outsized effects on the ELP grade. The use of proficiency thresholds (rather than a proficiency index) means that ELP-assessed schools receive no credit for students who approach but fail to meet the proficiency standard; they only receive credit when students “pass” the state’s EL assessment.[1] The ELP measure additionally tends toward an all-or-nothing points structure because ELP assigns points based on the performance of a single subgroup: English learners. Unlike the other gap closing measures, sub-par performance by EL students cannot be counter-balanced by the performance of another group.[2] For all these reasons, then, the performance of a very small number of EL’s can mean the difference between a 0 and 100 score on ELP.

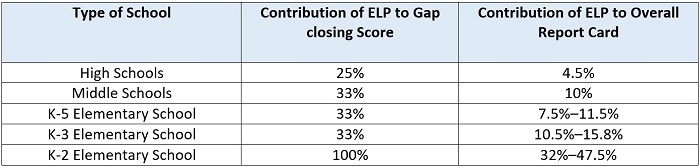

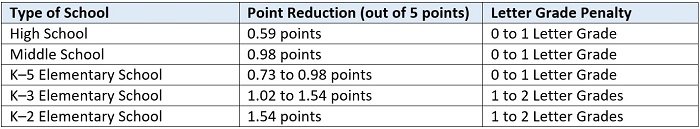

Of course, any accountability system necessarily imposes some types of thresholds. The system described above might be less troubling if the ELP measure played only a modest role in report card scores. But now we come to a third feature of ELP: its relatively heavy weighting in the overall gap closing score and, as a result, on the overall report card grade. As highlighted in Table 1, for most schools being held accountable for ELP gap closing, the performance of English learners constitutes one-third to one-quarter of the entire gap closing grade, but in rare circumstances it can comprise as much as 100 percent. This difference is due to the fact that not all schools are assessed on all possible components of gap closing.[3] Furthermore, because the Ohio report card system weights the overall gap closing component differently depending on a school’s population and grade configuration, gap closing itself can account for anywhere between 4.5 and 47.5 percent of a school’s overall report card grade. Somewhat oddly, there is currently no correlation between the weighting of ELP in a school’s overall report card grade and the percent EL students in a given school population.

Table 1: Contribution of ELP to Gap closing Score and to Overall Report Card Score

Why does this matter? The use of proficiency thresholds and the preponderance of all-or-nothing point allocations, when combined with the relatively heavy weighting of the ELP sub-component, creates an accountability system which permits dramatic shifts in gap closing scores and even overall report card scores based on the performance of a very small number of students.

For starters, Ohio’s system mechanically permits a school to be penalized up to four letter grades on the entire Gap Closing measure based on the failure of a single EL student to make adequate progress. This, for example, was the experience of New Albany Middle School in New Albany-Plain Local School District in 2019. Because the school missed that year’s ELP proficiency threshold of 51 percent by one student, it received 0 points for the ELP gap closing sub-component. Its overall gap closing grade, which would have been a 100 (an A) without ELP, was reduced to a 66.7—a D. The story did not end here, though. The school’s D grade on gap closing, in turn, had effects on its overall report card grade, which was reduced by nearly 0.98 points, lowering the letter grade from an A to a B.

Curious about the broader picture—in particular, how much a single student’s ELP performance could affect the overall report card grade of two otherwise identical schools—I created a dataset containing all possible combinations of report card scores for the achievement, progress, K–3 literacy, graduation rates, and Prepared for Success components. I then simulated the final report card grade for two schools with identical profiles except for their ELP gap closing measure: One school passes the threshold and receives 100 points for the sub-component, while the other fails by one student and receives 0 points. Results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: How Much Can One Student’s Performance in ELP Gap Closing Affect a School’s Overall Report Card Grade?

The simulation suggests that, based on the performance of a single EL student, a school can earn an overall report card grade that is as much as two letter grades lower as an otherwise identical school. Consistent with the findings of Table 1, Ohio’s small number of early-learning elementary schools are the hardest hit because gap-closing comprises nearly half of their overall report card grade. Middle and K–5 elementary schools, which are graded on three to four report card components, can easily see their report card grade fall by an entire letter grade. High schools are the least vulnerable, but depending on how close they are to the grade threshold, they can also see their grades reduced by a full letter grade.

****

Ohio’s 55,000 K–12 EL students deserve access to high-quality English language programs. They deserve the opportunity to achieve English proficiency and to fully participate in their schools’ broader academic programming. At the same time, however, Ohio communities deserve an accountability system which provides meaningful differentiation of school performance. Because of ELP’s flaws, Ohio’s current report card system fails this standard.

Ohio policymakers should return to the drawing board and construct an ELP measure that encourages districts to attend to the language acquisition needs of the state’s ELs and provides a fair assessment of their progress in moving students toward language proficiency.

[1] Schools can be granted partial improvement for credit, but thus far only a very small percentage of schools have qualified. A fuller treatment of this point, and of other issues discussed in this post, is available here.

[2] Technically, this criticism applies to all subgroup-level gap-closing measures, but the flaw is amplified in the ELP measure because the subgroup measure (EL performance on OELPA) is the only “input” into the sub-component (ELP gap closing). In contrast, in ELA and math gap-closing, the median number of subgroups assessed is four (and can be as high as ten). The final sub-component score for ELA and math takes the average score of all sub-groups.

[3] Elementary schools, for example, cannot be held accountable for graduation rates. K–2 schools are not subject to state testing in ELA and math, and hence are not held accountable for most achievement and progress indicators.

Effective communication is a two-way street that involves not only sending and receiving information, but also understanding it. Breakdowns can occur at any point. A new report from the Center for American Progress digs into the state of school-to-family communication, looking for strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities in this important endeavor.

Researchers Meg Benner and Abby Quirk build on previous studies which indicate that clear and consistent communication channels are an important way for schools to encourage family engagement. But the mere existence of a channel (weekly emails, monthly phone calls, regular conferences, etc.) is not enough. Even quantifiable participation by parents is not sufficient to ensure the desired engagement. Are schools sending the sorts of information parents want? Can parents understand what they receive? Does the information convey the tone which schools intend? Does it lead parents to take action? Is technology a help or a hindrance? The potential for miscommunication is high.

In fall 2019, Benner and Quirk recruited survey participants via a crowdsourcing data acquisition platform called CloudResearch. They set racial and ethnic targets for parent participants using the 2015 public school enrollment estimates—per the Common Core of Data files from the National Center for Education Statistics—for Asian/Pacific Islander, black, Hispanic, and white parents so as to obtain a nationally representative sample. The teachers and school leaders who participated in the survey, having no targets set during recruitment, were overwhelmingly white. In the end, they recruited 1,759 total participants in three categories: 932 parents, 419 teachers, and 408 school leaders. The vast majority of all respondents were associated with traditional district schools, although both charter schools and magnet schools were represented.

Overall, parents, teachers, and school leaders reported that schools’ communication of various information types is useful, and that parent engagement is strong. However, there were several notable discrepancies. For instance, 92 percent of parents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that they were “involved with their children’s learning,” while only 64 percent of teachers and 84 percent of school leaders agreed that parents were involved. School leaders were most likely to agree with the statement that parents were “involved with the school community”—85 percent of them agreed or strongly agreed—compared with 72 percent of parents and 69 percent of teachers.

Parents, teachers, and school leaders all rated individual student achievement (a catchall category without reference to specifics such as test scores or grades) as the most important type of information to communicate. Beyond that, though, important differences of opinion emerged. Parents rated curriculum information and resources related to college and career readiness as the next two types of information they desired, while teachers instead rated patterns of behavior and disciplinary action as their second and third choices, respectively. School leaders favored schoolwide achievement information as number two, followed by a raft of other things tied for (a distant) third.

While parents, teachers, and school leaders all reported that the school communicated information frequently, all said that ideal communication would be more frequent and more consistent. The ideal reported frequencies of conveying different types of information unfortunately varied widely among the categories of respondents (with parents and teachers wanting varying levels of increased frequency and school leaders wanting to stand pat or decrease frequency). Additionally, school leaders reported that the overall amount of information shared was increasingly too much as they moved from younger to older grades, while parents reported the amount as increasingly too little. An important divergence of opinion.

The report concludes with recommendations for federal, state, and district levels. They include schools surveying parents about their engagement and communication preferences, the feds maintaining Title I Parent Engagement funds, states providing technical assistance to schools to develop parent engagement plans, districts investing in technology advisors who can recommend parent-focused communication improvements, schools connecting information to individual student achievement whenever possible, school leaders reinforcing parent communication as a central responsibility of every teacher, and schools providing training and resources to ensure staff members have the capacity and tools to communicate with all parents.

SOURCE: Meg Benner and Abby Quirk, “One Size Does Not Fit All: Analyzing Different Approaches to Family-School Communication,” Center for American Progress (February, 2020).

Will social-emotional learning (SEL) be a passing fad, or something that becomes embodied in school culture? The answer likely hinges on whether it’s embraced by parents and educators, and its ability to improve student outcomes. A new study from the RAND Corporation casts some doubt on whether SEL programs can meet those ambitious goals.

In this report, analysts examine the implementation of an SEL program called Tools for Life (TFL) in Jackson Public Schools, a high-poverty Mississippi district of about 25,000 students. TFL aims to develop students’ SEL competencies and improve school climates. It includes eight to twelve classroom lessons per grade that help students recognize and manage their emotions. In addition, TFL asks teachers to use “calm down corners,” hang posters depicting various feelings, and wear lanyards that include problem-solving tools. In Jackson, guidance counselors delivered the TFL lessons every couple weeks in the elementary grades, while social studies teachers did so in middle schools. Consultants and coaches were hired to help support program delivery and provide professional development.

To implement TFL, Jackson randomly chose twenty-three schools to begin using TFL in 2016–17, while twenty-two additional schools waited until the next year. The staggered rollout allowed analysts to evaluate the short-term impacts of the SEL program by comparing pupil outcomes in schools in the first wave—the “treated” schools—versus those that were delayed until the next year. Outcomes include indicators of social-emotional competency (e.g., self-control or empathy), perceptions of school climate (e.g., matters of safety or trust), suspension and attendance rates, and state test scores. The SEL and school climate outcomes were measured via student survey, which the researchers note may suffer from self-reporting biases, while the other data were collected via district records.

The analysis finds no evidence that Jackson’s implementation of TFL improved pupil outcomes. After year one, no significant differences in SEL outcomes or school climate emerge between treated students and their peers. The impacts on attendance, suspensions, and test scores are all likewise insignificant. The point estimates, though not statistically significant, are slightly negative across a large majority of these outcomes. Moreover, analyses indicate that TFL still had no effect on SEL, school climate, or attendance and suspensions after two years of implementation (the district was unable to provide valid data to examine that year’s test scores).

Why the muted impact? While it’s hard to ascertain with certainty, surveys and interviews offer clues about why the program seems to have fallen short of its goals. For one, analysts discover uneven implementation across schools. For instance, among students in treated schools, anywhere from 63 to 100 percent said they’d experienced a TFL lesson. Meanwhile, in-depth fieldwork in several focal schools reveals concerns among educators. Some school staff, for example, thought that the program was too “light touch” and didn’t demand much effort or buy-in, especially from regular classroom teachers. Another worry that surfaced was the “low dosages,” as lessons were taught sporadically over the school year. Last but not least, the study found that “parental engagement was minimal,” limiting opportunities to reinforce at home what students were learning in school.

To sum up their study, the authors write the glum conclusion that the implementation of TFL in Jackson, Mississippi, was “uneven across schools, and in many cases, reportedly shallow.” Of course, it’s not clear whether the lackluster implementation is more a reflection of the TFL program itself, or a lack of capacity on the part of the district. Regardless, this report offers a lesson—and a reality check—about the challenges of SEL implementation.

Source: Gabriella C. Gonzalez, et. al., Social and Emotional Learning, School Climate, and School Safety: A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluation of Tools for Life® in Elementary and Middle Schools, RAND Corporation (2020).