How Ohio's walk back of graduation requirements is like overprotective parenting

By Jamie Davies O’Leary

By Jamie Davies O’Leary

In my book, state-level policymaking should be like good parenting. It should incentivize the behaviors you’re looking to inspire, grant autonomy (when your charges have earned it), and refrain from too much meddling or coddling. It should be transparent and honest, truthful about tradeoffs between short-term discomfort and long-term gain, and motivated by a clear compass rooted in what’s in the best interest of the kids’ wellbeing.

So why does Ohio’s latest softening on what we expect of our high schoolers bring to mind so many parallels to helicopter parenting? Allow me to explain.

I first learned about helicopter parenting from my husband, a psychotherapist who counsels a number of adolescents and young adults. Years ago, he began noting (broadly, never in specifics) that many young people he counseled seemed to lack the fortitude and emotional resilience to overcome basic life obstacles. For instance, they might have a panic attack after earning a “C” on a paper, find themselves bedridden with depression if they didn’t get into their first-choice college, or wind up suicidal after a break-up with a girlfriend or boyfriend.

A common thread among these clients was that their parents tended to “hover,” micromanaging their lives and worse yet protecting them from the natural consequences of their decisions and from the discomfort that comes with failure. At that point, the term “helicopter parenting” wasn’t yet part of my lexicon, nor had I seen expert takes from university deans, psychologists, or doctors that brought it fully into the mainstream. But I had heard enough to be suspicious of participation trophies and the self-esteem movement. I vowed that if and when I had children of my own, I’d allow them the dignity of facing the truth, even when—and maybe especially when—it included failure. It seemed clear that the alternative was infinitely worse, and much harder to recover from.

Since then, these themes have shown up somewhat unexpectedly in my own line of work—education policy. The “opt out movement,” wherein parents keep their kids home on state testing days, struck me as an offshoot of helicopter parenting—especially among those reluctant to expose children to stress or anxiety. (Certainly, there are kids for whom anxiety is a legitimate challenge, though such debilitating levels are arguably rare.)

Support for higher academic standards, which Ohio began moving toward in 2009, and the fight to overcome the “honesty gap”—the yawning chasm between states’ sunny numbers on student proficiency versus more rigorous national measures (e.g., NAEP or ACT)—made deep sense. It paralleled my nascent views on parenting and my antagonism toward helicoptering, inasmuch as I believed that if young people aren’t prepared for life—whether academically or emotionally—it’s better that parents know right away, while they still have time to adjust course.

Most recently, Ohio’s debate over graduation requirements has me looking through this lens again. Ohio lawmakers must decide whether to accept the recommendations passed by the State Board of Education this week to extend the latest “fix” to the classes of 2019 and 2020. This menu of options allows students to earn a diploma without demonstrating mastery in any academic content area. A new “jobs readiness seal” earned by completing a checklist of vague and subjective traits such as “global/intercultural fluency” and “dressing and acting appropriately” takes us even further away from the mark. Are we really ready to award diplomas so subjectively?

These options weaken what is already a somewhat meaningless diploma, amount to state-sanctioned low expectations, and set Ohio back three decades when it comes to expecting high school students to meet a basic threshold of competency in key subjects. (Ohio’s 117th General Assembly passed a law in 1987 that required the graduating class of 1994 and classes thereafter to pass ninth grade proficiency exams.)

Like helicoptering, creating competency-free options for young people to graduate is detrimental no matter how loving it’s intended to be. Students, rather than schools and adults charged with running them, will bear the costs down the line. And the cruel irony is that the students for whom we’ve created these alternatives, unlike those who are fiercely helicoptered, are far less likely to have a safety net to fall back on when their academic deficiencies catch up to them.

To some, criticizing the notion of diplomas-as-participation-trophies might come across as elitist. After all, who are we to stand between eighteen-year-olds and their high school diplomas? I worry less about the fact that we’re letting students off the hook than the reality that we’re letting schools off the hook. If Ohio lawmakers accept the State Board’s recommendation and extend these soft alternatives for several more years, they are tacitly agreeing with the idea that mastery is just not possible for some students.

At the end of the day, Ohio’s weakening of graduation standards reminds me of the most disturbing aspects of helicopter parenting. It represents the path of least resistance, regardless of the long-term consequences for students whose interests we’re supposed to protect. It robs students of the opportunity to work hard and achieve something meaningful. It allows adults to save face, albeit temporarily. And, sadly, the repercussions will likely not be felt until years down the line, once those same students enter a world for which they are utterly unprepared.

In case you missed it during the hustle and bustle of the holidays, Ohio recently announced how students can earn a new endorsement on their high school diplomas. It’s known as the OhioMeansJobs-Readiness Seal, and it’s intended to communicate to businesses that a student possesses the professional skills needed for employment.

To earn the seal, students must be deemed proficient[1] in fifteen professional skills, which include punctuality, teamwork and collaboration, and critical thinking and problem solving. Proficiency is determined by three mentors, who must complete and sign the validation form. Students choose their own mentors, but they must include adults from at least two of three state-prescribed areas: school, work, and community. Examples include teachers, coaches, work supervisors, or faith-based leaders.

The Ohio Department of Education (ODE) has a ton of information about the seal online, including this informational guide for teachers, students, and families. It’s in this document that ODE explains the rationale behind it: “Ohio businesses are seeking talented workers who have solid academic skills such as reading, writing and mathematics, as well as the professional skills required for success in the workplace.”

They are certainly correct about the importance of professional skills—often referred to as “soft skills.” These are valuable traits in the world of work, and undoubtedly why the General Assembly put the readiness seal into state law in the first place.

There is, of course, a debate to be had about the best way to gauge soft skills attainment. Plenty of stakeholders have legitimate concerns in this regard, including whether having student-chosen mentors sign off on mastery makes the process too open to gaming. But at least the state is trying to figure out a way to measure various behaviors and traits besides those easily evaluated by standardized tests.

Unfortunately, there’s a serious problem overshadowing all of this—not with the seal itself, but with the diplomas to which the seals will be affixed. By ODE’s own admission, businesses aren’t just looking for students with soft skills. They’re also looking for students with “solid academic skills such as reading, writing and mathematics.” Colleges and universities undoubtedly want the same. And although the work-ready endorsement is meant to indicate that a student possesses important soft skills, it’s the diploma that indicates the mastery of academic or “hard” skills.

In Ohio, however, that’s no longer the case—at least not for this year’s graduating class. Last spring, the state legislature approved additional graduation options for the class of 2018. The new pathways permit students to earn diplomas without passing end of course (EOC) exams, attaining college-ready targets on the SAT or ACT, or meeting career and technical requirements. Instead, students will only need to meet two of nine alternative conditions, a list that includes non-academic achievements such as 93 percent attendance or 120 hours of work/community service during their senior year. Earning the readiness seal is also one of these nine options. In short, some graduates in the class of 2018 will soon go out into the real world with seals that indicate their soft skills proficiency and a diploma that indicates many accomplishments—like school attendance or volunteer hours—but certainly not academic mastery. Functionally illiterate, but cooperative, teenagers will now earn high school diplomas. Are we sure that’s a good idea?

Across the country, graduation rates are rising while the value of a diploma continues to plummet. Some are starting to wonder if the high school diploma has lost its academic meaning altogether. In Ohio’s case, many of the recent diploma changes are the result of understandable concerns—policymakers and administrators don’t want to withhold diplomas based solely on test scores. But what often gets overlooked in the debate is why test scores matter in the first place: Without them, the state has no way to validate that students have mastered the academic content needed to succeed in the real world. Of course soft skills matter—but they are meaningless if they aren’t bolstered by hard, academic skills too.

[1] The Ohio Department of Education defines a proficient student as one who “has a deep understanding, can achieve a high standard routinely, takes responsibility for own work, deals with complex situations, makes decisions with confidence, and sees, overall, how individual actions influence outcomes.”

I don’t know about you, but for the most part, I shut down my social media and news apps over the winter holiday this year. As it turns out, tending to your neighbor’s chickens, building gingerbread houses, and riding sleds are all good strategies for recovering from the dumpster fire that was 2017. Meanwhile, some major education policy news in Ohio unfolded. Take a look at what you might have missed.

1) New Ohio right-to-work proposals were unveiled. Just before Christmas, Republican representatives John Becker and Craig Riedel introduced six Joint House Resolutions meant to scale back the power of public and private sector unions. Most notably, the proposals (HJR 7-12) would prohibit the automatic deduction of union dues from employee pay, forbid union fees from being spent for political purposes without permission from employees, and ban requirements imposed on contractors to pay workers the prevailing wage. Restrictions on dues would have enormous implications for teachers unions in Ohio. Agency fees are also a topic at the core of the U.S. Supreme Court case, Janus v. AFSCME (though the proposed resolutions go beyond union dues).

Right-to-work legislation in Ohio is certainly nothing new: Rep. Becker has proposed (less-reaching) iterations of it in the past, and few can forget the statewide referendum that repealed the historic overhaul of collective bargaining rights, Senate Bill 5, in 2012. The current goal is to get these proposals to the 2020 ballot and let voters decide for themselves (again)—a move that Akron Beacon Journal’s Doug Livingston says is unlikely given the somewhat onerous steps required (House leadership would need to move it to a floor vote, even after previous iterations died in the finance committee; then it would need a supermajority passage in the House; then follow the same process through the Senate). And lest we forget, Governor Kasich—who’d have to sign the resolutions—simply may not want to, given the overwhelming defeat of SB 5 and his own centrist political aspirations. Regardless of how far these particular proposals may get, expect right-to-work conversations to continue—whether through the Janus case or local initiatives.

2) ECOT’s final reckoning drew near(er). The nation’s largest e-school, now infamous to almost all Ohioans and many national observers as well, showed up in our 2017 ranking of top stories and is on the docket for education issues likely to continue to seize the spotlight in the new year. The Ohio Supreme Court has just announced February 13 as the date for hearing oral arguments in the case between ECOT and the Ohio Department of Education. If the court rules against ECOT, enabling the state to continue collecting $60 million in repayment, it could represent the final blow for the school.

Those of us who’ve watched this saga know that an ECOT closure would bring with it some major fallout. For starters, thousands of students would need to transfer to a brick-and-mortar school or to other statewide virtual charters. (Though only a small portion of ECOT students could do the latter; Ohio’s enrollment caps for e-schools limit the number of students who can enroll each year). If ECOT’s students are anywhere near as disadvantaged as the school claims they are—in ways that go beyond even demographic factors like socioeconomic status, disability, or race—receiving schools may have a tough job ahead to serve them well. Students who are severely credit deficient and off track to graduate in four years will take a toll on the Big 8 districts and others who enroll them. It also may send shock waves to Ohio’s other e-schools, many of which face similar repayments to the department and almost all of which are wondering how this case will ultimately shake out. Even so, it behooves the state to get it right on how it tracks student learning in virtual environments—not only to safeguard taxpayer money, but to protect students from shoddy instruction and falling behind. Either way, expect greater clarity when it comes to the logistics of attendance tracking and an ongoing debate about seat time, competency-based learning, school payments, and more.

3) Reducing the reliance on student test scores in teacher evaluations. In mid December, Sen. Lehner introduced SB 240, a bill that would move the state away from using student growth scores for up to half of a teacher’s rating and instead toward recommendations proposed by the Ohio Educator Standards Board last year. No longer would districts be required to use student data derived from the state-approved assessments as a portion of a teacher’s rating; instead, districts would be able to use other “high-quality student data” and to embed this into a revised Ohio Teacher Evaluation System rubric. Given that OTES failed to differentiate teachers—and that the student growth inclusion was a reason for serious backlash—SB 240 could be a sensible step in the right direction. Meanwhile, pay attention to which districts, if any, opt to continue using growth data in the current manner. Cleveland Schools CEO Eric Gordon has come out opposing the bill and vows to continue using student test scores to rate teachers regardless; his teachers union begs to disagree.

4) Newly signed computer science bill quietly modifies Ohio’s coursework requirements for graduation. In late December, Kasich signed HB 170, which requires academic content standards and a model curriculum for computer science for the first time. The legislation was passed in a largely bipartisan fashion and even earned support from Google during the hearing process. Interestingly, it enables high schoolers to take a computer science course in lieu of Algebra 2—a staple of Ohio’s core curriculum requirements for all students except those opting into a career-technical pathway. The new law does require districts to inform parents that “some institutions of higher education may require Algebra 2 for the purpose of college admission” and sign a document acknowledging this.

A quick glance at admission requirements for Ohio’s public universities (and several phone calls we conducted with college admissions counselors) indicates that nearly all of them would accept the “equivalent” of Algebra 2 in the form of computer science. That’s reassuring. But HB 170 seems to walk back Ohio’s Algebra 2 requirement without undergoing a serious debate about whether students need it in order to be college and career ready. To me, that seems like far bigger news than the creation of model curriculum or a push toward computer science careers—both of which are good moves in and of themselves.

Discussions on graduation requirements will no doubt continue this year, though I’m also hoping for more debates on the actual meat of what we’re requiring and why—e.g., Should we allow advanced computer science in place of Algebra 2 (and aren’t the concepts of Algebra 2 necessary to succeed in advanced computer science anyway)? What careers in computer science are available to folks who haven’t taken Algebra 2? Will schools be able to find qualified teachers to teach the subject well?

***

Here’s to hoping that this busy start to 2018 portends good things for education policy and the lives of the students it ultimately affects.

Creating school funding policy is a delicate juggling act for state leaders. Contentious issues include deciding the responsibilities of local and state governments; determining efficient and fair ways to allocate funds; and ensuring economically friendly tax policies while raising sufficient revenue. Those seeking a firmer grasp of these topics should read a recent policy brief by Urban Institute researchers Matthew Chingos and Kristin Blagg that summarizes funding across the U.S. Three points in particular are worth highlighting.

First, the analysts show that state governments have increased their contributions to public education since the 1930s. When that decade began, local revenues almost fully financed U.S. schools, contributing more than 80 cents of every dollar. Since then an increasing percentage has come from states. In most states today, local and state contributions each constitute about 45 percent of school funding; the federal government supplies the rest. Yet these funding statistics, authoritative as they may be, arguably understate the true role of state governments in financing public education. In Ohio, for example, districts must levy a minimum 2 percent property tax in order to receive state funds. While these revenues are deemed “local,” they are integral to the state funding program and might be better categorized as state funds.[1]

Second, Chingos and Blagg look at the relationship between districts’ capacity to generate local funds and the educational needs of their pupils. Conventional wisdom suggests that low-capacity districts—those with weak property-tax bases—educate the neediest students. This is true in some cases. For instance, the property-poor Dayton school district serves a disproportionate number of students from low-income families. But, in eleven of the sixteen states analyzed in this paper, districts’ property wealth and poverty rates are weakly correlated; the other five (including Ohio) show a somewhat closer link. The point is this: Relying on property wealth alone to target state money doesn’t necessarily ensure that districts serving low-income students receive the funds they need. To Ohio’s credit, it now incorporates resident income into its formula (though in a complicated way) and provides additional aid for economically disadvantaged students.

Third, the brief finds that 72 percent of state dollars nationwide are distributed via formula aid, or general assistance grants, and the rest comes from categorical aid designated for specific programs or students, such as special education, transportation, and gifted or bilingual programs. But the ratio varies across states. In Ohio, for example, formula aid constitutes 90 percent of state funding. Yet it accounts for less than half in places like Connecticut, Florida, and South Carolina. As the Chingos and Blagg mention, categorical funding can restrict districts’ flexibility while formula-based aid is generally less rigid.[2] They don’t argue strongly for one over the other, but many school reformers favor more flexible formula-driven aid so long as states hold schools accountable for outcomes. As a recent paper from Foundation for Excellence in Education argues, “Districts are in the best position to decide which services are most beneficial for their students and should have maximum flexibility to do so. Funding restrictions harm this important flexibility.” Following this idea, states such as California have enacted reforms that shift from categorical to formula aid.

The analysts touch on other important matters in school finance too. Overall, the policy brief is a worthwhile introduction to the complex world of school funding policy.

Source: Matthew Chingos and Kristin Blagg, “Making Sense of State School Funding Policy,” Urban Institute (2017).

[1] Voter-approved property tax revenue generated above the 2 percent floor is more clearly local.

[2] Some formula aid has restrictions and could almost be seen as “categorical.” For instance, Ohio’s economically disadvantaged funding is considered part of the formula-based aid though state law limits how funds can be used.

The state board of education voted today to recommend that the General Assembly extend previously-relaxed graduation requirements for the class of 2018 to the classes of 2019 and 2020.

“Despite consistent feedback that too many Ohio high school graduates aren’t ready for credit bearing college courses and don’t possess the skills necessary to enter the workforce, the state board of education is once again recommending that the legislature walk back the requirements for high school graduation,” said Chad L. Aldis, vice president for Ohio policy and advocacy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. “What’s most disappointing is that this change is being recommended even though a significant majority of Ohio students have met the more rigorous graduation requirements.”

The most recent data released by the Ohio Department of Education projects that almost 77 percent of students in the class of 2018 are on track to meet graduation requirements.

Rather than earning a diploma by successfully passing end-of-course exams, achieving remediation-free scores on the ACT or SAT, or attaining an industry credential and demonstrating workforce skills, students in the classes of 2019 and 2020 would be able to graduate by completing two of nine tasks from a list which includes a 93 percent senior year attendance rate, holding down a part time job or a volunteer position for 120 hours, and earning a 2.5 grade point average in their senior year.

“While supporters of this change are likely to make this a referendum on testing, this is really a question of whether Ohio high school graduates should be able to demonstrate a basic level of competency in math, reading, science, and American history,” Aldis added. “This change is ostensibly being recommended to help struggling students, but it’s these very students who most need the academic skills that are supposed to accompany a diploma.”

The recommendation would need to be approved by the General Assembly and Governor Kasich before it can go into effect.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

There’s no doubt about it: We have a graduation rate problem in the United States. However, one of the biggest problems might not be what you think. It is not simply the hundreds of thousands of students failing to graduate on time or the hundreds of thousands of graduates who leave high school but still require remediation upon postsecondary enrollment. One of the most challenging yet least talked about problems is the four-year cohort graduation rate calculation itself.

While students are enrolled in a typical high school for four years—grades nine to twelve—the four-year cohort graduation rate calculation waits until the fourth year to account for their progress toward graduation. After four years, a student is stamped with a one-time designation of “graduated on time” or “did not graduate on time.”

That approach makes sense in a world in which students attend the same high school all four years. But in an increasing number of communities, that is no longer the world we live in. Especially with the advent of online schools and other choice options, many students now attend multiple schools over the course of their high school experience. Yet only the school that last enrolled a student is evaluated for her success or failure.

A recent report by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute said of students who transfer high schools:

“Receiving schools become fully accountable for transfer students’ on-time graduation, though they may have fallen significantly behind while in their former school. High schools that enroll large numbers of credit-deficient students are especially at risk of low ratings when this calculation is utilized.”

The example outlined below illustrates how failure by schools in the first three years of high school can be masked in year four when students transfer.

[[{"fid":"119853","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"default"}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"1"}}]]

Waiting until year four to capture a student’s graduation status may make sense for schools where the student population is relatively stable. But what happens if a school receives dozens of new high school students each year? Or maybe even hundreds? An analysis of fourteen online schools of varying sizes, geographic locations, and student populations found that more than half of all high school students were new to those schools in 2015-16. Of those newly enrolled students, 50 percent of them arrived credit deficient. This means that the students fell behind in a prior school and are off track for an on-time graduation, yet the prior school faces no accountability for their failure.

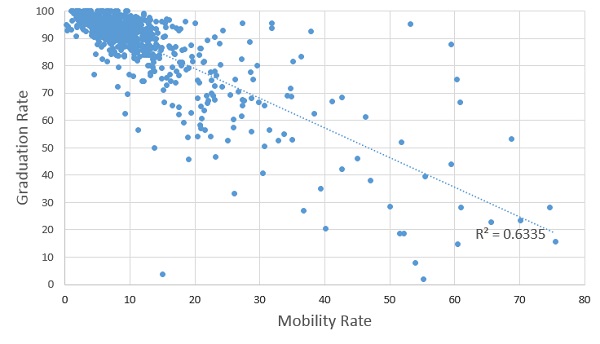

In Ohio, schools with more than 25 percent of enrolled students enrolling in or out are called highly mobile schools. For these schools, the four-year cohort graduation rate metric skews especially negative due in part to the instability of the student population, as evidenced below in the analysis of highly mobile schools compared to traditional schools in the state of Ohio.

[[{"fid":"119855","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"3":{"format":"default"}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"3"}}]]

Using the Ohio data, it becomes very apparent that there is a negative relationship between graduation rate and mobility rate—meaning the higher the mobility rate, the lower the graduation rate. In fact, highly mobile schools have an average graduation rate that is 31 percentage points lower than that of less mobile schools. While some of this could be due to other student factors like income status, there is no doubt that the relationship between school mobility rates and graduation rates is more than just chance. These data lead to the question: Are we truly measuring how successfully a school is improving students’ ability to graduate on time, or are we simply calculating a rate that reflects the mobility of the student population?

Furthermore, have we created a perverse incentive for brick-and-mortar high schools to encourage their under-credit students to transfer to online schools in order to inflate their graduation rates?

Given this analysis, we need to rethink our approach to graduation rate and take a more student-centered approach. We have two recommendations.

First, instead of waiting to capture a graduation status for a student after year four, hold schools accountable for adequate progress toward graduation for all students in year one, two, three, and four. Measuring annual progress toward graduation for every student ensures that every school is accountable for the progress (or lack thereof) of every student every year. For more about this approach, read the four-part series here.

Second, in addition to the four-year cohort graduation rate, calculate a graduation rate for each school that only accounts for students served by the school for all four years, starting in ninth grade. Doing this ensures a level playing field for highly mobile schools and allows for more equitable comparisons between all schools. Going back to the fourteen online schools serving highly mobile populations, utilizing the traditional four-year cohort calculation would result in a 40 percent graduation rate. However, calculating the rate for only students enrolled for all four years would result in a rate double that at 80 percent.

Before we can even begin to address many of the other graduation rate problems that we face in the United States, it is absolutely imperative that we ensure we are utilizing the proper metrics to measure student and school success. We join our voices with the Fordham report and call on state lawmakers, both in Ohio and elsewhere, to explore graduation rate calculations that hold high schools accountable for what is under their control. Make every student matter, every year, for every school, in every state.

Jessica Shopoff, M.Ed. and Chase Eskelsen, M.Ed. are on the Academic Policy and Public Affairs teams for K12 Inc., an online learning provider.

One of the perils of working at a think tank, especially one like Fordham, which encourages provocative ideas and never shies away from a debate, is that it can be easy to anger or frustrate even your closest allies. That’s especially true in this polarized, fraught time we’re living in. I’m mindful of this dynamic and actively work to make the necessary policy arguments without being unnecessarily inflammatory. Alas, I’m not always successful.

In December, I received a thoughtful email from a friend and (often) ally regarding Fordham’s continued insistence that the alternative graduation requirements adopted last year amounted to a diploma giveaway and would hurt Ohio students in the long term. The person argued that our position was wrong and simply hadn’t kept up with conventional wisdom or the latest research. A productive email exchange filled with research citations, a litany of real-world examples, and a few logical inferences followed. At the end of the day, we still didn’t agree, but I was better as a result of the dialogue.

The holiday break gave me some time to think more about the interaction and one particular frustration expressed in this exchange. Namely, it’s one thing to oppose a policy proposal, but in situations where a resolution is needed, you also need to bring solutions to the table.[1]

That’s a great reminder of how easy it is to be a critic, an armchair quarterback that simply looks at others’ ideas and points out flaws or questions motives. Many of us are addicted to this particular sport, given the countless hours we spend watching talking heads on CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC spouting sound bites designed for maximum political impact. Then there’s Twitter and Facebook, which allow each of us to be pundits and to receive praise from our like-minded friends and family, making us all feel both smart and insightful. Unfortunately, it often makes matters worse.

Don’t misunderstand me. I work at a think tank. There’s nothing wrong with having an opinion that puts you in disagreement with another person’s approach to resolving a problem. And yes, we at Fordham often express our viewpoints in a passionate way. However, we can’t just say “you’re wrong,” “that won’t work,” or (worse yet) resort to hyperbole and ad hominem attacks: “you’re trying to destroy America/Ohio/etc.” This approach, while it may generate press clippings, rarely solves problems.

As the New Year begins, I resolve to be more than a critic and will make every effort to be solution-oriented. Here are some principles that I’ll keep at the forefront of my work in the coming year:

If successful, the return on this resolution is likely to be more productive conversations, better relationships, an increased chance to learn something in the process, and most importantly, being far better positioned to actually make a difference.

As Theodore Roosevelt eloquently stated, “It is not the critic who counts. ... The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena; whose face is marred by the dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly ... who, at worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly; so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory or defeat.”

In the coming year, let’s take our ideas and enter the arena. See you there.

[1]Fordham did advocate last year for a number of policy solutions that would address graduation requirements for the class of 2018. Expect to see those ideas and maybe a couple of new ones later in January.