The Impact of Ohio Charter Schools on Student Outcomes, 2016–19

Since the first Ohio charter schools opened in 1998, they’ve regularly been subject to intense scrutiny

Since the first Ohio charter schools opened in 1998, they’ve regularly been subject to intense scrutiny

Since the first Ohio charter schools opened in 1998, they’ve regularly been subject to intense scrutiny. Detractors have criticized their academic performance, while advocates have pointed to bright spots within the sector. The competing narratives often give policymakers and the public mixed signals about the performance of these independently-run public schools that today educate just over 100,000 Ohio students.

Fordham’s latest report presents up-to-date evidence about the performance of the state’s charter schools. Dr. Stéphane Lavertu of The Ohio State University conducted a rigorous analysis of student-level data from 2015–16 through 2018–19.

Among his important findings:

We urge you to download the report to see for yourself the benefits that Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools provide for students.

* * * * *

On October 6, 2020, report author Stéphane Lavertu presented his findings at a virtual event. The complete video of that event can be viewed below or on our YouTube channel here.

A recent article from the Tribune Chronicle in Northeast Ohio covered a school funding analysis published by the personal finance website WalletHub. Several district officials offered comments in response to the analysis, but the spokesperson for Youngstown City Schools directly challenged the study’s data:

Youngstown City School District spokeswoman Denise Dick questioned the per-pupil expenditure numbers provided by WalletHub. Youngstown ranked 52 out of 610 school districts in Ohio. It, according to the report, is the sixth-most equitable district in Trumbull and Mahoning counties.

The district’s per student expenditure is $19,156, according to the report. Dick, however, said the most recent per pupil spending numbers actually are closer to $12,634.

“I don’t think our per-pupil spending has ever been as high as what’s listed in the article,” she said.

The sizeable discrepancy in spending reported by Wallet Hub and cited by Ms. Dick—a roughly $6,500 per pupil difference—certainly raises eyebrows. What gives? The answer is wonky (stick with me!) but important. It also points to the need for a change in the way Ohio reports spending on its school report cards.

First off, the WalletHub data. It relies on U.S. Census Bureau data on K–12 expenditures in districts across the nation, which does indeed report Youngstown’s at $19,156 per pupil for FY 2018. This amount takes into account operational spending—dollars used to pay teachers and staff, buy textbooks, and the like—but excludes capital outlays. The Census Bureau’s technical documentation also makes clear that the agency removes state dollars that “pass through” Ohio school districts and transfer to charter schools, alleviating a concern about federal statistics that has been raised by local school finance expert Howard Fleeter.

While an error is unlikely, it’s worth cross-checking the census data against state statistics. The go-to state source for fiscal data is the Ohio Department of Education’s District Profile Reports, also known as the “Cupp Reports,” which were named long ago after veteran lawmaker and current House Speaker Bob Cupp. Youngstown’s report states that the district spent $18,284 per pupil in FY 2018. That’s not an exact match to WalletHub, but it’s within shouting distance—and far closer than the amount cited by the Youngstown official. Much like the Census Bureau, ODE’s expenditure per pupil data capture operational expenses and exclude capital expenses and dollars that pass through districts to charters.[1]

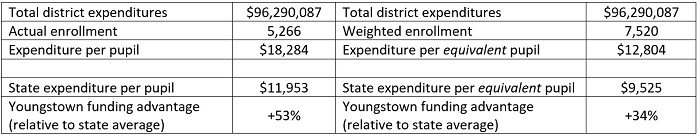

Where then does the $12,634 come from? As it turns out, it comes from the state report card which, lo and behold, tells us that Youngstown spent this sum in FY 2019.[2] But what’s crucial to understand about this source of fiscal data is that, per state law, report cards display an expenditure per equivalent pupil. The basic idea behind this particular statistic is to adjust a district’s actual per pupil expenditures to account for the extra costs associated with educating economically disadvantaged students, English language learners, and students with disabilities. The table below illustrates this methodology using data from Youngstown. The key difference is that the expenditure per equivalent pupil relies on a weighted enrollment—the aforementioned subgroups are effectively counted as more than one student—rather than actual headcounts. In a district such as Youngstown, which serves large numbers of economically disadvantaged students, the weighted enrollment can end up being significantly higher than the actual enrollment.[3]

Table 1: Expenditure calculations for Youngstown City Schools, FY 2018

There are pluses and minuses to the equivalent pupil method of reporting expenditures. On the upside, it creates fairer comparisons of district spending by trying to gauge the amount being spent on a “typical” student. Youngstown’s equivalent amount implies that it spends $12,804 per average student, 34 percent above what the average Ohio district spends on a typical student. This suggests that its spending is somewhat out of line with the state average, though less so than under the actual expenditure calculations. The downside of the equivalent methodology is that it significantly “deflates” the amount of actual spending in districts across Ohio, including Youngstown. This could mislead citizens who are unlikely to think about spending in terms of “equivalent” pupils and who, as surveys indicate, already vastly underestimate the amounts that public schools actually spend.

To clear up the confusion, Ohio lawmakers should require that actual expenditure per pupil amounts be featured prominently on school report cards, just like they are on the Cupp Reports. The equivalent spending data could be maintained as supplemental data, but they must be clearly marked as adjusted amounts that attempt to account for the expenses associated with educating students who usually have greater needs. There should also be an explanation of the methodological differences (including the enrollments used in the denominators), so that users can better distinguish between the two data points.

Productive discussions about school funding—and potential reform of the system—rely on transparent spending data. But as the story from Northeast Ohio reminds us, the wires can get crossed even among people who work in education. By omitting actual spending amounts, the current report card system displays numbers that are out of step with conventional spending data. A more complete presentation of the data is needed to offer a full picture of the resources being dedicated to educate Ohio students.

[1] Unfortunately, the Cupp Report’s per-pupil revenue statistics do not remove funds that transfer to charter schools, thus inflating some district’s revenues. Youngstown’s per-pupil revenues were $25,839 in FY 2018, but that is not an accurate reflection of the dollars received to educate district students.

[2] Youngstown spent $12,804 per equivalent pupil in FY 2018.

[3] In FY 2018, Youngstown reported 100 percent economically disadvantaged students (versus 48 percent statewide), 18 percent students with disabilities (versus 15 percent statewide), and 7 percent English language learners (versus 3 percent statewide).

When coronavirus turned everything upside down this spring, there were predictions that educators would retire in droves rather than risk teaching during a pandemic.

According to a recent piece in the Columbus Dispatch, those predictions didn’t quite come true. At least not in Ohio. Nick Treneff, the spokesperson for Ohio’s State Teachers Retirement System, told the Dispatch that prior to July, the number of submitted retirement applications was hovering around 2,500—similar to previous years. But when it became clear the pandemic wasn’t ending anytime soon and reopening conversations became controversial, ensuing numbers more than doubled: 370 teachers applied for retirement in the weeks leading up to the start of the 2020–21 school year, compared to only 183 in the previous year. Treneff confirmed for the Dispatch that it was “a higher number than we might have expected but not a huge rush to the door.” He also noted that Ohio has around 190,000 active teachers, so the unexpected retirement of nearly 200 shouldn’t be too worrisome.

That might be true, but that doesn’t mean Ohio is out of the woods in terms of a teacher shortage. It’s important to acknowledge that retirement was only a viable option for a small number of teachers. To receive unreduced retirement benefits, Ohio teachers must either have thirty-three years of service or be sixty-five years old and have at least five years of service. Even receiving reduced retirement benefits requires teachers to be older or have decades of experience. That means that for younger teachers, retirement wasn’t much of a choice—pandemic or not. If they didn’t feel safe returning to the classroom and there was no remote teaching option, they could either take a leave of absence (if they could get one approved) or resign and find another career.

Unfortunately, the retirement numbers are the only hard data we have about how teachers are responding to the pandemic. To the best of my knowledge, Ohio has no centralized database that tracks teacher leaves of absence. It’s also too early for the state to have solid numbers about how many teachers resigned this year, let alone how many cited the pandemic as their reason for leaving the classroom.

Even if those numbers are as low as the relatively small spike in retirees discussed above, the impact could be significant. For instance, to cover for teachers who are on a temporary leave of absence—or those who are in quarantine because of their exposure to the virus—districts will need more substitute teachers than in previous years. During normal times, good substitutes are hard to find because it’s a difficult job that doesn’t pay well. The pandemic will likely make things harder. Joe Clark, the superintendent at Nordonia City Schools in northeast Ohio, told the Akron Beacon Journal that just two days into the school year, he was already struggling to find substitutes. “It’s a whole bunch of things coming together at the wrong time,” he said. “For the amount of pay they get, it might not be worth it to say, ‘I’m going to take that risk to come in and sub for a day.’”

Prior to the pandemic, teacher shortages were far more nuanced than most headlines intimated. Most were confined to certain geographic locations and content areas. For instance, Ohio’s rural districts occasionally have a hard time competing for teacher talent in difficult-to-staff subjects, in part because they have lower-than-average salaries. It’s also harder to recruit young talent to rural areas. Data indicate difficulties in staffing subjects like special education, math, science, and career and technical education. Overall, though, teacher shortages weren’t significant across the board.

Covid-19 could change that. With an uptick in retirements, an unknown number of resignations and leaves of absence, and an unprecedented health crisis that could continue to drive teachers out of the classroom, Ohio and other states might soon be staring down the barrel of a wide-ranging teacher shortage. If that is indeed the case, the prospective teacher pipeline will become more important than ever. There is evidence that economic downturns can push previously uninterested jobseekers into teaching. But will that be enough?

Given the stark learning losses caused by school closures, the quality of incoming teachers will also matter immensely. Now is the time for the state to take bold steps to attract a horde of talented individuals into the classroom—steps like increasing starting teacher salaries and investing in alternative teacher preparation programs that produce effective teachers. The financial costs for such moves will be steep upfront. But the long-term payoff for students, their communities, and the state as a whole will be worth it.

Over the last few years, states have attempted to offer a clearer picture of how well high schools prepare students for the future by measuring college and career readiness (CCR), instead of just student achievement and graduation rates. In a recently published report, Lynne Graziano and Chad Aldeman of Bellwether Education Partners outline the pros and cons of several CCR measures. They also identify whether states are designing these measures to ensure equity and discourage funneling certain groups of students into less demanding pathways and restricting their access to more rigorous and potentially lucrative options.

First, the authors examine the “promises and perils” of several CCR measures that states currently incorporate into their accountability systems. They include:

To understand what CCR data states are collecting, the authors followed the “scavenger hunt” approach used by the Data Quality Campaign to evaluate state report cards. They focused on three main inquiries: 1) if the state reports a CCR indicator; 2) whether the CCR indicator is reported using a single measure or broken down into multiple subcomponents; and 3) whether results are disaggregated by race, gender, socioeconomic status, and other factors.

The most common CCR measure is advanced coursework, which is used by forty-one states. Thirty-nine states utilize a career-based measure, which could include CTE course-taking, work-based learning, industry credential completion, or apprenticeships. Twenty-seven states based at least a portion of their CCR indicators on college-admissions assessments like the SAT or ACT, and fourteen states rely on military measures like enlistment or scores on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery test. Thirteen states use post-graduation measures such as postsecondary enrollment or enrollment without remediation.

Only four states—Alaska, Maine, Nevada, and Oregon—are not currently reporting any form of CCR. However, although the majority of states track readiness, most do not disaggregate the results by specific pathways or demographic groups. Only sixteen states broke down the results of their indicators according to all the demographic categories required by federal education law. Unfortunately, without tracking these results, states have no way of identifying access and equity issues.

Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia incorporate CCR measures into their formal accountability systems. Fifteen of those states break their indicators down into subcomponents. For example, South Carolina has nine criteria for its CCR measure—five components for college readiness and four for career readiness—and they account for 25 percent of a high school’s rating. Another nine states also utilize subcomponents, but do not weight each one for accountability purposes. The specific weight given to the CCR indicator varies by state, and ranges from as low as 5 percent in Michigan and Iowa to 40 percent in New Hampshire.

The report closes with several recommendations. First, the four states that lack a CCR measure and the twelve that have a measure but omit it from their formal rating systems should shift immediately toward tracking readiness and holding schools accountable for it. Next, information about which pathways are most helpful for improving postsecondary readiness and success should be made more readily available to students and families. Finally, states should provide more opportunities for researchers and policymakers to explore data in a systematic way. Doing so would allow advocates to determine whether certain student subgroups are being tracked toward, or away from, certain CCR pathways, and could help policymakers make better decisions going forward.

Source: Lynne Graziano and Chad Aldeman, “College and Career Readiness, or a New Form of Tracking?” Bellwether Education Partners (September 2020).

Before the coming of the pandemic, pre-K was a hot topic. It was seen by many as an efficient and reliable way of making sure that our youngest learners—especially those from less-privileged backgrounds—were ready to hit the ground running when their time for kindergarten arrived. And while research generally backs up the notion of a readiness boost, especially as compared to children starting kindergarten without the benefit of formal pre-K, many studies have found that the pre-K advantage tends to fade, even evaporate, during the early years of elementary school. New research from a team led by Ohio State University professor Arya Ansari aims to find out whether this phenomenon is the result of fadeout—that is, pre-K students losing ground starting in kindergarten—or a result of students new to formal schooling catching up with their peers.

This study looks at a sample of low-income kindergarten students in a large, unnamed school district in an anonymous mid-Atlantic state. The total sample comprised 2,581 children whose family income made them eligible for publicly funded preschool in the year prior. Within the sample, there were 1,334 children who had previously attended pre-K (called “attenders”) and 1,247 “non-attenders” whose first experience in formal schooling was kindergarten. Sixty-two percent of the total sample was Hispanic, 12 percent was Black, 11 percent was White, and 15 percent were another race or ethnicity. This diversity was not representative of either the district or the county and should serve as a flag on at least part of the methodology. While both groups in the sample were eligible for preschool, we have no information on why those who chose to avail themselves of it did so, nor why the others did not. Families of 59 percent of students reported speaking Spanish at home, 17 percent reported speaking English, and 24 percent reported speaking another language. Perhaps those non-English speakers who opted for pre-K were looking for language immersion as much or more so than they were looking for an intro to fractions and sharing.

All students were evaluated across a battery of surveys and tests in both the fall and spring. All children were assessed in English unless they failed the language screener. Significantly for this heavily-Spanish-speaking sample, fall tests for those failing the language screener were conducted in Spanish. However, all children were assessed in English in the spring, regardless of language proficiency score at that time. Students’ academic achievement was measured via Woodcock Johnson III. Executive functioning was assessed via established tests of working memory, inhibitory control, and the like. Teachers answered questions on conduct and peer relationships to measure social-emotional skills. The children were also surveyed on their individual kindergarten classroom experiences, including how they felt about their teacher, their classmates, and their general enjoyment of school.

Consistent with previous research, Ansari and his team observed stronger academic skills and executive function among pre-K attenders at the start of the kindergarten year, as compared to their non-attending peers. But there was also clear evidence that both of these gaps narrowed by the end of kindergarten. All children in both groups demonstrated improvements in their academic and executive function skills. However, attenders made smaller improvements than did non-attenders. By spring, attenders’ initial advantage had been cut by more than half in academic skills and nearly half in executive functioning. Pre-K attenders also lost ground in social-emotional skills, although the differences between the groups was very small in both fall and spring. Overall, the researchers conclude that this gap-closing is primarily a result of non-attenders catching up, not attenders slowing down. They also determined that just one-quarter of this gap-closing was being driven by factors inside the classroom—namely, that many of the skills being learned in kindergarten were easy for non-attenders to pick up once instruction got started for them—and that factors outside the classroom and out of their realm of study must be responsible for the other three-quarters.

However, selection bias, as noted above, cannot be ruled out as a contributor to the findings. While a random assignment study of this type is likely difficult to create, it would be the best way to truly investigate the factors at work here. More rigorous studies have shown that, while low-income students will typically start kindergarten below their higher-income peers—in terms of readiness—with or without pre-K “treatment,” fadeout of the type observed here is not inevitable. One such report in 2017 identified several schools across the state of Florida, which bucked that trend with a vengeance. Success is likely down to the classroom and the individual teacher, and the “special sauce” has proven elusive. Perhaps the teachers in this study simply ignored the readiness level of the attenders and started at the beginning for every child. That could explain both the convergence of academic skills and the observed lowering of social-emotional skills and “elevated levels of conduct problems” among attenders.

Giving kids a great start in kindergarten is too important an endeavor to leave to chance. We cannot simply blame outside factors when we know that kindergarten (and pre-K for that matter) works for some kids and not for others. If the evidence of pre-K fadeout is found in the kindergarten classroom, that is where it must be defined and combatted.

SOURCE: Arya Ansari, et. al., “Persistence and convergence: The end of kindergarten outcomes of pre-K graduates and their nonattending peers,” Developmental Psychology (October 2020).

Last week, we at Fordham released our latest report on charter schools in Ohio. The research, conducted by Dr. Stéphane Lavertu of The Ohio State University, examines the most up-to-date evidence about the performance of the state’s charter schools, which educate just over 100,000 children.

In a virtual event on Wednesday, Dr. Lavertu presented his findings to over 100 attendees. He began by noting that although charter schools were created to provide families with a high-quality educational choice, the charter sector in Ohio hasn’t always been high performing. Fortunately, this new research indicates that the sector has improved significantly in recent years.

The study focuses on brick-and-mortar, general education charter schools in Ohio from 2016 through 2019. It examines academic achievement, but also non-academic outcomes such as attendance and behavior. By using a variety of statistical methods to compare students who are virtually identical other than their enrollment in a charter or traditional public school, Dr. Lavertu was able to track changes in the outcomes of individual students over time.

The results for charter schools serving students in grades 4–8 are encouraging. In both math and English language arts, the data “indicate greater gains in achievement from year to year for students attending charter schools as opposed to traditional public schools.” If a student were to attend a charter school for five consecutive years, their average achievement in both subjects would be approximately 0.3 standard deviations greater than it would have been if they attended a traditional public school. That’s the equivalent of moving from the 30th to the 40th percentile, and adds up to roughly an extra year’s worth of learning. These effects were largest for low-achieving students, Black students, and students in urban districts. Data on attendance and behavior were also positive.

The results for charter high schools are slightly more complicated due to methodological concerns, but the findings remain encouraging. The analysis examined End of Course exams in math and reading—specifically the English I, English II, Algebra I, and Geometry state exams—as well as the ACT. Results indicate fairly large and significant effects on the English exams. The effects in math were also positive, though not statistically significant. ACT findings were also statistically insignificant, though Dr. Lavertu noted that data limitations may have prevented precise estimates. As was the case with schools serving younger grades, charter high schools demonstrated positive effects in attendance and behavior measures, and overall effects were the largest for students who were low-achieving, Black, or residing in urban districts.

To conclude his remarks, Dr. Lavertu emphasized that his findings point to charter schools as a worthy investment for public tax dollars. “It seems pretty clear that expanding Ohio charter schools could be a highly cost-effective option for improving student outcomes,” he said. He noted that this is particularly true now, as the state struggles to cope with school closures and learning losses brought about by the coronavirus.

The presentation was followed by a question and answer session for event attendees. One question sought to determine whether the charter school improvements reflected in the new report could be attributed to House Bill 2, legislation from 2015 that strengthened accountability for charter schools. “I can’t say it’s because of House Bill 2,” Dr. Lavertu replied. But he did acknowledge that “something happened,” and that it “seems to be the case” that charters have improved since the legislation was passed.

In response to a question about whether the state should invest more dollars in expanding charter schools, Dr. Lavertu said that there is “some encouraging evidence” that points to the impact of increased spending on student outcomes, especially in schools that receive less funding, as charters in Ohio do. However, Dr. Lavertu cautioned that increased investment must be done wisely. “In terms of expansion, I think that has to be done really carefully,” he said. “What you want to do is replicate models that work, make sure that they’re scalable, that there’s a labor supply…and that you’re enrolling the students who need it the most.” Well put, and here’s hoping that the state and local communities continue to create environments suitable for growing great charter schools.