More Ohio students are earning industry-recognized credentials

In the last decade, Ohio leaders have advocated for an increased focus on career and technical education.

In the last decade, Ohio leaders have advocated for an increased focus on career and technical education.

In the last decade, Ohio leaders have advocated for an increased focus on career and technical education. Among the initiatives in this area is a push for industry-recognized credentials (IRCs), which verify that a student has mastered a specific skillset within a particular industry. These credentials provide a host of potential benefits to a wide range of stakeholders. They can, for example, lead to well-paying jobs for students, identify qualified candidates for employers who are hiring, and contribute to a healthy statewide economy.

To harness the potential of IRCs, Ohio lawmakers have incorporated them into several major education policies. First, IRCs are a key part of the Prepared for Success component on school report cards. As the component name suggests, it gauges how well students are prepared for success in postsecondary education or the workforce. One of the primary measures of readiness is the percentage of students who earn an IRC or a group of credentials totaling twelve “points” in one of thirteen career fields. Second, the Ohio General Assembly passed a law that allowed students beginning in the class of 2018 to meet graduation requirements by earning an IRC and meeting other career-related criteria. Although Ohio’s graduation requirements have since changed, IRCs continue to be a pathway toward graduation. It’s also worth noting that the most recent state budget established a $25 million appropriation dedicated to helping high school students earn IRCs.

Clearly, credentials are now a significant part of Ohio’s education landscape. But are students actually earning them? The most recent state report card data say yes—and reveal a steady upward trend, which indicates that policy changes emphasizing IRCs have acted as an incentive for schools to encourage students to earn credentials.

Let’s start with the state-level data. Because of the cancellation of state tests this spring due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the recently released 2019–20 state report cards lack a considerable amount of information. Fortunately, this isn’t an issue when it comes to Prepared for Success because the component relies on data from previous graduating classes that finished high school prior to the pandemic.

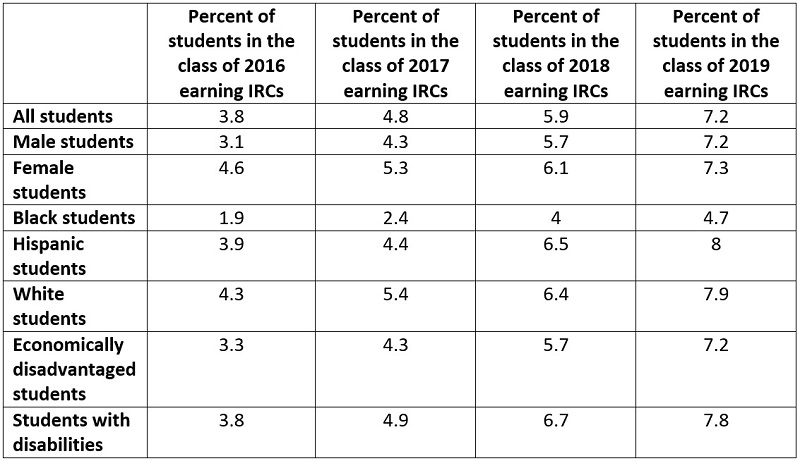

The table below highlights the percentage of students who have earned IRCs in each graduating class over the last four years. The biggest takeaway is that the percentage has increased every year since 2016, the first year that Prepared for Success was a graded component. Just 3.8 percent of students in the class of 2016 earned IRCs, but the total has since increased to 7.2 percent for the class of 2019. Subgroup breakdowns also reveal increases across the board. The percentage of Black, Hispanic, economically disadvantaged, and students with disabilities who earned an IRC prior to graduation has doubled since 2016.

To be clear, the overall number of students earning an IRC is still small. Only 7 percent of students in the class of 2019 earned a credential. Nevertheless, steady growth should be celebrated—especially when it occurs for a diverse group of students.

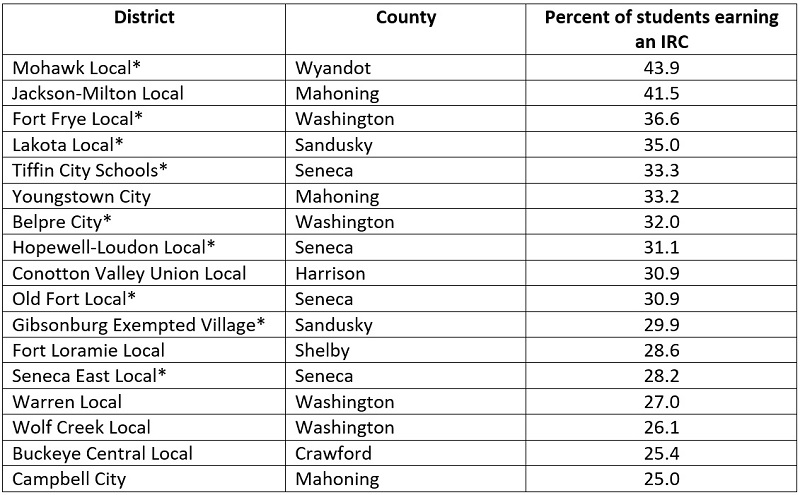

Some Ohio districts are doing especially well in regard to IRC attainment. The table below highlights seventeen districts where a quarter or more of the class of 2019 earned IRCs. Many of these districts also had high percentages of students earning credentials the previous year. The nine districts with asterisks beside their name reached 25 percent during the 2018–19 school year, as well.

As was the case with overall percentages, it’s important to put district results in perspective. Ohio has 610 traditional school districts, which means just under 3 percent of districts had a quarter or more of their most recent graduating class earn a credential. That’s a tiny number. But it is a start, and the state’s emphasis on attainment isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. It’s fair to expect that more districts will end up on this list in the future.

What does all this mean for Ohio? Well, there’s good news and bad news. The good news is that more students are earning industry-recognized credentials that could help open doors to rewarding careers. The bad news is that the state doesn’t make data on what these credentials are and whether they qualify as “high quality” readily available to the public.

Last year, The Foundation for Excellence in Education and Burning Glass Technologies released a report called Credentials Matter that offered an in-depth look at the industry credential landscape. To determine which credentials were in demand, Burning Glass used its proprietary dataset to search nearly 40,000 online job boards, newspapers, and employer sites for job postings that requested specific credentials or skills. They found that, nationally, only 19 percent of credentials earned by the K–12 students in their analysis were actually in demand by employers. In fact, of the top fifteen most commonly earned credentials, ten were oversupplied. In Ohio, specifically, more than 49,000 credentials were earned by high school students—not just those in the graduating class—during the 2017–18 school year. But fewer than 13,000 of them were considered in demand. Over 17,000 were for basic first aid or occupational safety—useful, to be sure, but not what most people think of when they think of IRCs.

Going forward, Ohio should take a few important steps to make sure that IRCs live up to their potential. The state already has a framework for determining which IRCs can be counted toward graduation and the Prepared for Success measurement, and the application process to add new credentials seems pretty rigorous. Ohio leaders deserve kudos for these guardrails and should keep them in place. But to ensure more transparency and objectivity in the process, policymakers should also work to link approved credentials to labor market outcomes, and then publish this information in an easy-to-access format that students and families can use to make informed decisions.

Ohio should also begin disaggregating credentialing data by career field or even individual certification on state report cards. The state breaks down how many students earn credentials in each district and school, and it tracks the overall attainment of subgroups from year to year. That’s a good start. But to get a sense of whether students are earning high quality credentials, Ohio should also track and publish the specific credentials students earn. Without these data, it’s impossible to know whether recent increases in attainment are actually beneficial—or just empty numbers.

Overall, Ohio has made encouraging progress in the realm of industry-recognized credentials. Attainment numbers are on the rise for a diverse group of students, and that’s good news. But to truly leverage the potential of IRCs for students, state leaders need to ensure that available credentials are linked to positive outcomes, and that those outcomes are transparent for everyone.

Stephen Dyer, longtime critic of public charter schools, now employed by the anti-charter-schools teachers union, recently wrote a lengthy response—a so-called “evaluation”—to the charter school study by Ohio State’s Stéphane Lavertu and published by Fordham. He accuses us of “cherry picking schools; manipulating data; [and] grasping at straws,” and he lodges a number of other complaints, some of which have little to do with the study itself.

The following responds to his criticisms. Excerpts from Dyer’s piece are reprinted below and italicized; my responses follow them in normal font.

* * *

“The group’s latest report—The Impact of Ohio Charter Schools on Student Outcomes, 2016-2019—is yet another attempt to make Ohio’s famously poor performing charter school sector seem not quite as bad (though I give them kudos for admitting the obvious—that for-profit operators don’t do a good job educating kids and we need continued tougher oversight of the sector).”

The purpose of this study isn’t to make Ohio charter schools look “good” or “bad”—it’s to offer a comprehensive evaluation of charter school performance that can drive an evidence-based discussion about charter school policy. To that end, we asked Dr. Stéphane Lavertu, a respected scholar at The Ohio State University, to conduct an independent analysis of charter performance. His research relies on the most recent data available (2015–16 through 2018–19) and uses rigorous statistical methods that control for students’ baseline achievement and observable demographic characteristics to isolate the effects of charters apart from the backgrounds of the pupils they enroll. Had Lavertu’s analyses revealed inferior performance, we would have published that, too. (Fordham has released studies that found mixed results for choice programs in the past.) The data, however, reveal superior performance among Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools (see page 13 of the report), with especially strong, positive impacts for Black students (page 14). When all charters are included in the analysis (including e-schools and dropout recovery), charter students still make significant gains in English language arts (and hold their own in math) relative to similar district students in the most recent year of available data (page 24).

Apparently, these results don’t fit with Dyer’s agenda, so he would rather question the motivations of the study. He is also wrong in claiming that “for-profit operators don’t do a good job educating kids.” On the contrary, the study finds that, in grades four through eight, brick-and-mortar charter schools with for-profit operators outperform districts that educate similar students (see page 17). Yes, you read that right. The results of charters with non-profit management operators, however, do outpace those opting to contract with for-profits.

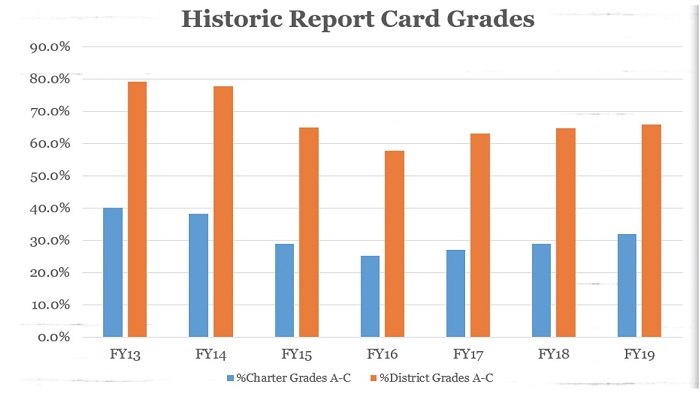

“But folks, really. On the whole, Ohio charter schools are not very good. For example, of all the potential A–F grades charters could have received since that system was adopted in the 2012–2013 school year, Ohio charter schools have received more F’s than all other grades combined.” [Following figure is his.]

This is a ridiculous apples-to-oranges comparison. In fact, given Dyer’s lede (and keeping with the produce metaphors), it seems only fitting to call it an egregious attempt to cherry-pick using data that include much wealthier districts. The figure compares charter school performance to all Ohio school districts statewide, many of which serve students from more affluent backgrounds. Due to longstanding state policy, Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools are concentrated in high-poverty urban areas. In turn, charters serve disproportionately numbers of low-income and minority students who, as research has consistently documented, achieve on average at lower levels than their peers (thus explaining charters’ lower ratings relative to all districts in Ohio).[1] In 2018–19, Ohio charters (brick-and-mortar and online together) enrolled 57 percent Black or Hispanic students versus a statewide average of 23 percent. Charters also enrolled more economically disadvantaged students: 81 percent versus 50 percent statewide.

A fair apples-to-apples evaluation, sans cherry-picking, takes into account these differences in pupil background by comparing the academic trajectories of very similar charter and district students. This is exactly what Lavertu does. What Dyer shows is mostly the achievement gap between students of lower socioeconomic status versus those from more advantaged backgrounds. It’s not evidence about the effectiveness of Ohio charters. Almost everyone realizes that the lower proficiency rates of Cleveland school district students to Solon or Rocky River reflects to a certain extent differences in pupil backgrounds. Why wouldn’t the same apply to Cleveland charter schools?

“Fordham ignored all but a fraction of the Ohio charter schools in operation during the FY16-FY19 school years, including Ohio’s scandalously poor performing e-schools (yes, ECOT was still running then), the state’s nationally embarrassing dropout recovery charter schools (which have difficulty graduating even 10 percent of their students in 8 years), and the state’s special education schools—some of whom have been cited for habitually billing taxpayers for students they never had.”

The report didn’t ignore anything. The focus was intentionally on general-education, brick-and-mortar charters—a point we make clear in the foreword. These schools serve as parents’ primary public-school alternative to traditional district options in the places where charters are allowed to locate. If you’re a parent considering a site-based charter school for your child that isn’t focused on academic remediation, you might want to know how these schools perform on average. (Prior charter evaluations have combined the results of brick-and-mortar charters with those of e-schools and dropout-recovery schools, thus masking brick-and-mortar performance.) So yes, for good reason, there was a focus on brick-and-mortar charters.

Dyer misleads when he says that brick-and-mortar charters represent “a fraction of Ohio charter schools.” In FYs 2016–19, these schools enrolled between 56 to 62 percent of all Ohio charter students (page 23 of the report). That’s a fraction all right. It also happens to be a majority. Importantly, these site-based schools serve 83 percent of all Ohio charters’ Black students and 72 percent of the sector’s economically disadvantaged pupils.[2]

He is also wrong in claiming that the results of virtual, dropout-recovery, and special-education schools were “ignored.” Despite serious methodological challenges in evaluating these schools’ impacts—Lavertu discusses those on pages 11 and 24—the analysis gauges the performance of all Ohio charter schools (page 22–24), and these specialized schools’ results appear separately on page 68.

Moreover, suggesting that Fordham has ignored e-schools over the years is absurd. In fact, we released an entire report in 2016 that focused exclusively on Ohio’s e-school performance, and we’ve been engaged in the policy discussions aimed at improving the quality of online learning—an educational model that, due to the pandemic, almost all of us can now agree has unique challenges.

As for the “embarrassing” graduation rates of dropout-recovery schools, they are likely as much a reflection of the failures of students’ former school—often in their home district—as the charter school in which they subsequently enroll. (By definition, dropout-recovery schools enroll primarily students who have dropped out or are at risk of doing so.) Fordham has called for a more comprehensive way of evaluating dropout recovery charter schools, including a “shared accountability” framework that would split responsibility for students’ graduation (or not) based on the proportion of time spent in each high school.

“The “performance gains” they point to are not impressive.

For example, “Students attending charter schools from grades 4 to 8 improved from the 30th percentile on state math and English language arts exams to about the 40th percentile. High school students showed little or no gains on end-of-course exams.”

Really? A not-even-10-percentile improvement? And none in high school? That’s it?”

Dyer is unimpressed with a 10 percentile gain for charter students attending brick-and-mortar charters in grades four through eight (as opposed to attending district schools). There is some room for debate around what constitutes a “large” or “impressive” effect size, which Lavertu discusses in the report (pages 32–33). Within the context of studies about other educational interventions, Lavertu suggests these effects—which are equivalent to roughly an extra year of learning accumulated over these grades—should be viewed as “large.” Rather than enjoying what researchers would consider large academic gains, it seems that Dyer would prefer that these charter students languish in district schools, staying at the 30th percentile.

As for the high school achievement results, it’s important to note that Dyer quotes from the Columbus Dispatch’s coverage of our report. It’s not a quote from the study. While the evidence is not quite as convincing that brick-and-mortar charter high schools produce large academic gains, the estimates are positive across all four state English and math end-of-course exams—and positive and statistically significant on both English EOCs. Lavertu’s analysis suggests positive effects on ACT scores, though the estimates do not reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

“How about this: ‘Attending a charter school in high school had no impact on the likelihood a student would receive a diploma.’

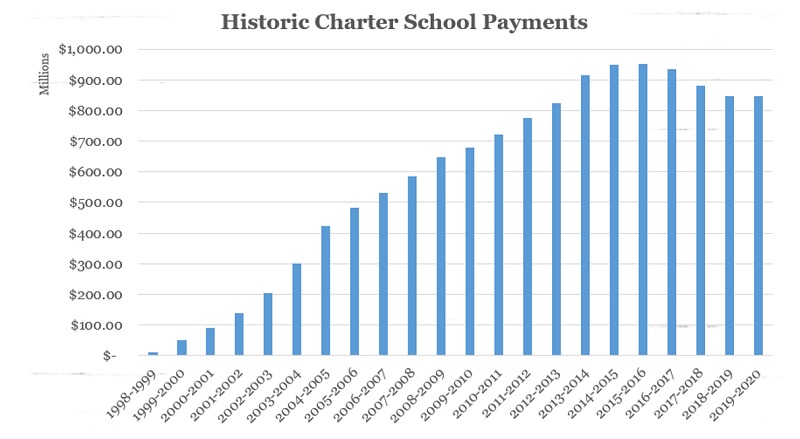

So we spend $828 million a year sending state money to charters that could go to kids in local public schools to have literally zero impact on attaining a diploma?

Egad.” [Following figure is his.]

This chart is nonsense. The reason that charter schools have received increasing amounts of state funding since FY99 is because they’re serving an increasing number of students (see the enrollment trend here). State dollars were simply moving to charters—the schools that were responsible for these students’ educations—as more parents were choosing this educational option. Meanwhile, contrary to Dyer’s suggestion that funding charter schools is an inefficient use of taxpayer money, charters represent a cost-effective educational option as they presently produce statistically equivalent outcomes (in terms of graduation) and superior performance on state exams—all at a lower cost than districts.

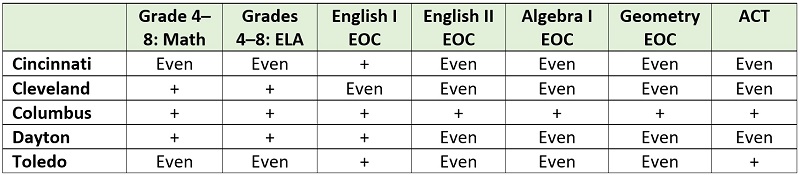

“The report found better performance from charter students in at least one of the math or English standardized tests in five of Ohio’s eight major urban districts (Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown). Only in Columbus did they outperform the district in both reading and math.

The report ignores that ECOT took more kids from Columbus in these years than any other charter school in Columbus. And, of course, those kids did far worse than Columbus students.

But even cherry-picking students. And data. And methodology, Fordham only found slightly better performance in one of two tests the study examined (again, Ohio requires tests in many subjects, but I digress) in five urban districts, better performance in both tests in one, and no better performance in Cincinnati and Toledo, which lost about $500 million in state revenue to charters during these four years the study examined.”

It’s hard to be sure what’s being referred to here. It does contain a gratuitous ECOT mention designed to incite outrage. It’s true, we didn’t like ECOT either. Dyer seems to express concerns that charters aren’t doing well enough to justify state funding by pointing to specific city-level results. The table below summarizes city-level test results for brick-and-mortar charters in grades four through eight and high school (see pages 16 and 27), and it sure seems that charters are a pretty good investment. On a battery of academic outcomes, charters perform either on par with the local district (i.e., there is no statistically significant difference in results, denoted as “Even”) or produce significant gains (“+”). And keep in mind that charter schools in these cities receive about 70 cents on the dollar in public funding compared to district schools. Seen that way, the return on investment is through the roof.

“Of course, the study also ignored that about ½ of all charter school students do NOT come from the major urban districts, including large percentages of students in many of the brick and mortar schools Fordham examined for this study. For example, about 30 percent of Breakthrough Schools students in Cleveland don’t come from Cleveland. Yet Breakthrough’s performance is always only compared with Cleveland.”

This concern is irrelevant because Lavertu compares very similar charter and district students. Even if the home district of a student attending a Breakthrough school is, say, Parma, she would be compared to a district student with similar baseline achievement and observable demographics. Moreover, he also examines a subset of students who attended the same elementary and middle school—children likely to be residing in the same neighborhood—and then subsequently transitioned to charter or district schools. The results from these analyses are very similar, revealing yet again a charter school advantage. Overall, Lavertu examines charter performance from virtually every possible angle, and the results hold up.

“More than 34 percent of Ohio public school graduates have a college degree within six years. Just 12.7 percent of charter school graduates do.

More than 58 percent of Ohio public school graduates are enrolled in college within two years; only 37.2 percent of Ohio charter school graduates are.”

This is another example of cherry-picking. Again, charter schools educate students of very different backgrounds to the average Ohio district. Though an analysis of post-secondary outcomes was not part of Lavertu’s analysis, state data show that charters’ college enrollment and completion rates, as cited above by Dyer, track more closely with the averages of Ohio’s urban schools—a more appropriate point of comparison. Fifteen percent of urban high school graduates complete college within six years, and 42 percent enroll in college within two years.

“In more than one in five Ohio charter schools, more than 15 percent of their teachers teach outside their accredited subjects

The median percentage of inexperienced teachers in Ohio charter schools is 34.1 percent. The median in an Ohio public school building is 6 percent.”

These teacher statistics have little to do with student outcomes. There is evidence, for instance, based on Teach For America evaluations that less-experienced teachers can perform on par—if not better—than more-experienced teachers.

“During the time period this report examined, nearly $4 billion in state money was transferred from kids in local public school districts to Ohio’s privately run charter schools.”

Fascinating. Money was “transferred from kids in local public school districts” to “privately run charter schools.” In one sector, dollars belong to the kids. In the other, they belong to institutions. Which is it? Of course, the answer is that the dollars belong to kids, whether they attend a district or charter school. When students transfer from, say, Akron to Hudson school district (or vice versa), the dollars should move with the child—a “backpack funding” principle. The same applies for charter schools, and indeed when Ohio students exit a district, the state funding designated for their education moves to their school of attendance (though local funding stays with the district). There is nothing wrong with dollars transferring from traditional districts to public charter schools when students choose an alternative option.

“Maybe the answer, especially during this pandemic, is expanding ‘high-quality’ local public school buildings, or investing at least some of the $828 million currently being sent to Ohio’s mostly poor performing charter schools back to local public schools so they have a better shot at being dubbed ‘high quality,’ thereby expanding the number of ‘high-quality’ options for students?”

We agree that there are exceptionally high performing traditional district schools, and celebrate that fact. At the end of the day, Fordham believes that all high quality schools—whether district, public charter, STEM, joint-vocational, or private—should receive the resources and opportunities to expand and serve more students. In our view, this study clearly indicates that, based on performance, supporting quality charter schools is a promising policy avenue that can unlock greater educational opportunities for more Ohio students.

Last year, hundreds of business and industry leaders, educators, state policymakers, and advocates gathered in downtown Columbus for Aim Hire, a day-long conference focused on workforce development hosted by Ohio Excels and the Governor’s Office of Workforce Transformation. Thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic, this year’s event looks a little different—rather than a single, day-long affair, there are five separate virtual events sprinkled throughout the fall—but the importance of the convening and the information it provides hasn’t lessened.

Take, for instance, the third virtual session, “Building Cred: Ohio Workers Benefit from Earning Industry-Recognized Credentials.” The event opened with remarks from Rob Brundrett, the director of public policy at the Ohio Manufacturers’ Association (OMA). He noted that manufacturing is Ohio’s number one industry, and that the Buckeye State is the third largest manufacturing state in the country. While there are relatively high unemployment numbers due to Covid-19, manufacturing continues to face serious workforce shortages despite being the “powerhouse” of the state’s economy.

To shed some light on these shortages, Sara Tracy, the Managing Director of Workforce Services at OMA, spoke with two members of the association. Amy Meyer, the Chief Organizational Development Officer at the Rhinestahl Corporation, discussed how her organization has prioritized developing a talent pipeline. “We know now, and in the next ten to fifteen years, we’re all going to continue to struggle with the students that come into manufacturing,” she shared. “We need employees and we need skilled tradespersons...so we roll up our sleeves and we have the mission of filling programs with students who can potentially have a great career in manufacturing.”

Ms. Meyer acknowledged that credentials have become increasingly important over the last few years, and shared that her company views them as an opportunity to “raise the bar” for themselves, their region, and the state as a whole. “The better our workforces are skilled...the more we get to say to our toughest customers, you know, we can handle it here.” Marzell Brown, the Talent Acquisition Lead at Rockwell Automation, echoed those sentiments. He shared that his organization has “a ton of folks who go through those credentialing programs.” Because they are backed by industry-recognized companies, students are able to get “legitimate” credentials in high school that can lead to a job and help them earn college credit.

Mr. Brown also emphasized how important it is to ensure that credentials “stand the test of time” and are truly meaningful for students. To that end, he spoke about how his company has worked with districts in Cleveland and several inner-ring suburbs to create robotics programs for high schoolers. These programs, in concert with additional local partnerships, make it possible for students to earn all twelve points needed to complete one of the state’s graduation pathways. The programs are also linked to postsecondary options—namely at Tri-C, the local community college. “We have a number of pathways and drop in and drop off points based on where a student wants to go,” he said.

Next, John Sherwood, the Workforce Project Manager for the Governor’s Office of Workforce Transformation, spoke about the state’s recently created TechCred program. He described how the overarching goal of the initiative is to help Ohioans earn industry-recognized, technology-focused credentials and to help businesses upskill both current and potential employees. To accomplish this, the General Assembly allocated just over $12 million per year for two years to reimburse employers for bearing the cost of credential training for employees. Both Ms. Meyer and Mr. Brown touted the benefits of TechCred. “I think the state has done a phenomenal job of putting their money where their mouth was on this one,” Mr. Brown said. Ms. Meyer agreed. “Tech Cred dollars and the ease with which that process has been happening has been a game changer for Rhinestahl…we couldn’t do upskilling and credentialing without that help,” she said.

They aren’t the only ones who approve. So far, the program has been a hit. After five application periods, 983 different Ohio employers were awarded a slice of the $12 million, resulting in 11,941 credentials versus the state’s original goal of 10,000. Mr. Sherwood pointed out that there are “a ton of repeat customers” due to the simplicity and efficiency of both the application process and the program itself. 268 employers received awards in multiple rounds. The pandemic hasn’t seemed to dull the interest, either. “Going into the first application period during Covid-19, we were a little unsure,” he shared. But by the end of June, the state was looking at a record-setting application period. “The crisis and the new way we’re conducting business...has accelerated demand for technical skills. We’ve seen even more companies interested,” he said.

Mr. Sherwood noted that because the program is paid for through the state budget, funding will need to be included in the next budget that will be proposed in 2021. Given the current fiscal crisis caused by Covid-19, state leaders are taking a critical look at all programs. Nothing is guaranteed. But Mr. Sherwood expressed optimism. “I think the success of TechCred thus far makes a really good case for the continuation of the program,” he said.

The same could be said for all of Ohio’s industry-recognized credentialing efforts. The number of students who are earning a credential prior to high school graduation has risen, and employer demand for TechCred signals that credentialing numbers are growing outside the K–12 sector, as well. Attainment Goal 2025 is still looming in the distance, and it’ll be a steep climb to ensure that Ohio can meet its target of 65 percent of adults having a post-secondary credential or certification. But one thing’s for certain: Ohio’s leaders and businesses are stepping up to help the state reach its lofty goal.

When the coronavirus pandemic forced schools nationwide to close their doors abruptly last spring, it imposed similar difficulties onto schools of all types across the country. But responses to those difficulties—restarting academics, maintaining student engagement, conducting academic testing, providing support services, issuing grades, keeping extracurriculars going, etc.—were rarely similar. In short, some schools responded more effectively to the crisis than others.

Several reports, including one from Fordham, have already sought to shine a spotlight on schools that made smoother transitions. An excellent new publication from Bellwether Education Partners and Teach For America adds to this growing literature. Analysts compiled case studies of twelve charter and district schools from across the United States that, by their reckoning, produced a high level of success during a difficult time. They find that the particular circumstances in each school and community led to unique needs, varied responses, and numerous versions of success.

Bellwether and TFA examine schools’ and districts’ successes and struggles in eight areas: providing human capital support and adjustments, innovating instructional content and approaches, serving special student populations, big-picture planning and establishing core principles, designing data-intensive approaches, focusing on social-emotional learning, creating supportive school-student connections, and building relationships with families and community.

By and large, the distance learning model that emerged in each of the profiled schools bore a strong resemblance to the model each building was already implementing prior to the pandemic. For example, KIPP’s high school here in Columbus, Ohio, (which the Fordham Foundation is proud to oversee as its authorizer) already had a strong technology foundation—providing Wi-Fi enabled devices to each student and having an established routine of doing work and submitting it via those devices. Thus the switch to accessing materials and turning in assignments from home required minimal adaptation. Nampa School District #131 in suburban Boise already employed a rigorous and multi-pronged model for teaching its English language (EL) learners. The remote version played out similarly during synchronous learning in large groups, live meetings in smaller groups with an EL specialist, and asynchronous “homework” delivered via teacher-created videos. The major innovation was additional outreach by EL teachers to students’ families to support them not only in language work, but also in other academic areas and in the area of personal well-being. This was felt to be possible only because the existing EL teaching framework had been strong and adaptable before being tested by Covid-19.

Universally, the schools and districts profiled prioritized personal support of students and their families over academics in the initial weeks of closure. While they weren’t able to directly provide all that families needed during the crisis, meeting basic needs loomed large for families, so those efforts took precedence. The examples enumerated are heartening and often ingenious, drawing on pre-existing relationships between schools and community service providers. The return to teaching and learning took many paths, often requiring intensive planning over a couple of weeks. The less “digital” the school had been beforehand, the more new training and software were required for both teachers and students. Breakthrough Schools, a charter network in Cleveland, Ohio, spent three weeks sequentially building their plan—and their capacity—for a remote learning model combining synchronous and asynchronous learning in varying percentages based on grade level. The Breakthrough process was goal-oriented, with each goal met leading to the next step. They were required to overcome a broad digital insufficiency among their students to even reach the intended starting line. And even when their remote model was operational, they continued to refine it based on parent and student feedback, which was actively sought by staff members.

Despite all of the positives, Bellwether and TFA are clear in pointing out that not everything worked, and that those things that did work at one school might not do so at others. There is no one answer. In particular, all schools struggled to develop effective strategies for serving students with disabilities, a challenge that predates the pandemic in many schools. With much in the way of grading, testing, and accountability curtailed or suspended across the country, the academic impacts of various remote learning models may not ever be fully knowable.

The education treadmill is endless, it seems, even when the system itself is brought to a crashing halt. These “promising practices,” as the report’s authors term them, are worth exploring in this level of detail, especially as remote and hybrid models of education are likely to remain widely used for the foreseeable future. “The ‘right’ approach to distance learning may well be embedded in these case studies,” they conclude, “but we don’t yet have the data or distance to determine what that approach is.” Instead, they offer this surfeit of information and detail “in the absence of knowing what schools should do.” That sounds about as right a mindset as any as we navigate these times.

SOURCE: Ashley LiBetti, Lynne Graziano, and Jennifer O’Neal Schiess, “Promise in the Time of Quarantine: Exploring Schools’ Responses to COVID-19,” Bellwether Education Partners (October 2020).

Research has shown that the human visual system is generally better at processing information that’s oriented in the horizontal and vertical planes—that is, up and down or left and right—in relation to the viewer, than information oriented at other, slanted angles. In the natural world, for example, our visual systems are better with tree trunks and flat landscapes than sloped roofs and hillsides. The modern built environment contains a preponderance of horizontal and vertical lines, but research is unclear as to whether our visual systems have adapted to the built environment or whether we’ve built that environment to suit our natural preference.

A new paper published in the journal Perception takes this investigation into the digital world where students, teachers, and parents have all been spending a lot more time since March. Lucky for all of us, it seems that human visual processing is more complex, and more adaptable, than previously thought.

The researchers first needed to create a brand new method of testing human response to visual stimuli, one that did not require any motor component other than the focusing of the eyes. By removing any other motor component—pointing, clicking, or even speaking—they could see directly and in real time subjects’ ability to detect target stimuli amid visual “noise” in photographs simply by focusing their eyes on it. The “noise” consisted of randomly-placed white squiggles on a dark background and the targets were a set of five or six aligned squiggles amid them. As in previous, motor-mediated tests, angled targets were detected slower and less accurately than were horizontally- and vertically-oriented targets.

Armed with this new tool, the researchers dropped their college student subjects into the virtual world to see how four hours of immersion in the popular—and rigidly vertical/horizontal—online game Minecraft might change their responses. Both the treatment and control groups were given the visual stimuli test first. Control group members were asked to limit their screen time (including video games, TV, and smart phones) for the same four-hour period that the treatment group was in the game mining, building, adventuring, and avoiding its hostile 8-bit mobs. Then the visual stimuli test was repeated on both groups to see what, if any, changes in response could be detected.

The treatment group showed a modest but statistically-significant boost in the speed and accuracy of their detection of vertical and horizontal stimuli. Though neither group evidenced any changes in their ability to detect stimuli on slanted angles. The researchers conclude that, far from damaging young eyes, virtual immersion of this type (a 2D rendering of the 3D world) provides benefits that can extend into the real world.

The human visual processing system, likely more complex than originally thought, shows robust adaptability far beyond real-world stimuli. The question of which came first—the horizontal world or our preference for it—remains unanswered. This research, however, seems to set the stage for the ultimate answer. And it’s an important question because we’re facing a new version of the built environment: the virtual built environment. And it looks like we’re all required to adapt to more screen time for a good while to come.

SOURCE: Daniel Hipp, Sara Olsen, Peter Gerhardstein, “Mind-Craft: Exploring the Effect of Digital Visual Experience on Changes to Orientation Sensitivity in Visual Contour Perception,” Perception (October 2020).