In national debates over charter schools, truth matters

In late July, the Democratic Party released a policy platform that included stances on a variety of issues, including education.

In late July, the Democratic Party released a policy platform that included stances on a variety of issues, including education.

In late July, the Democratic Party released a policy platform that included stances on a variety of issues, including education. Although there appears to be some debate about what, exactly, the platform says in regard to charter schools, there are definitely some ideas that should give school choice advocates pause. Consider this statement:

We support measures to increase accountability for charter schools, including by requiring all charter schools to meet the same standards of transparency as traditional public schools, including with regard to civil rights protections, racial equity, admissions practices, disciplinary procedures, and school finances.

At first glance, that seems reasonable. Charter schools should be held accountable for the way they educate their students, and having solid policies that promote transparency is crucial. But calling for charter schools to “meet the same standards” as traditional schools suggests that they are not currently doing so—and that’s inaccurate.

Let’s start with accountability. The federal Every Student Succeeds Act outlines the basics of a school accountability system that states must implement if they want access to federal funding. State leaders get to determine the nuts and bolts of these systems, including how student achievement and growth data will be collected, calculated, and published. All public schools are subject to the conditions and consequences that are born from this combination of federal and state requirements. And since charter schools are public schools, that means they’re held to the same standards as traditional district schools.

Furthermore, charter schools face much higher stakes under these accountability systems. If traditional district schools perform poorly on a consistent basis, they may, in very rare situations, be subject to state-led intervention efforts. But in Ohio and several other states, if charters perform poorly, the state will close them down automatically, and permanently.

Charter schools also have an additional layer of accountability thanks to their sponsors (a.k.a. “authorizers”), the organizations tasked with overseeing them. In Ohio, sponsors are evaluated using a rigorous system, and poor or ineffective ratings can result in sponsorship authority being revoked. This puts pressure on sponsors to close low-performing schools before they impact sponsor ratings. Within the last few years, dozens of Ohio charters have closed as a result. And it’s not just sponsors that charters must answer to. A charter reform law passed in 2015 required charter schools to meet a slew of new transparency and accountability standards—several of which are more rigorous than what their district peers are subjected to.

Finally, charters face competitive pressures that districts are almost entirely insulated from. If families don’t like the way a charter school is run, they aren’t forced to attend. If families don’t like the way their district school is run, on the other hand, their options are often much more limited. Many have just two options: They can either move to a new district—a costly and often impossible option—or hope there’s a school of choice nearby.

Thus, accountability for charter schools is already at maximum. There’s no need to “increase” anything there.

But what about the other issues identified in the platform? The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights notes that civil rights laws “prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin, sex, disability, and on the basis of age.” They must be followed by any school that receives federal funding. The same goes for laws like the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, which protects the privacy of student education records, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which governs special education services. As is the case with academic accountability, charter schools are required to follow all of these laws. So, once again, they are held to the same standards and consequences as traditional schools.

That leaves issues such as admissions practices, disciplinary procedures, and school finances. This is where things get complicated because education governance in the United States is complex. Many of these policies are established and implemented at the state level, which means they vary from state to state. But in general, charters are still held to the same—or higher—standards as traditional public schools. For example, when it comes to admissions, oversubscribed charters must use lotteries to admit students if they want to remain eligible for federal start up dollars. The same can’t be said for oversubscribed magnet schools in traditional districts. Student discipline policies in all public schools, charter and district alike, must adhere to the same federal civil rights rules, including reporting discipline rates. And as far as finances go, charters tend to get less money than their district peers but are still held to similar reporting requirements.

To be clear, it’s important for charter schools to be held accountable. They receive public money and are responsible for educating kids, and that means they must be subject to rigorous and transparent accountability policies. But a platform suggesting that charter schools aren’t held to the same standards as traditional public schools is misleading and, in states like Ohio, completely incorrect.

There are plenty of reasons why Democrats should support school choice. And policy advisers to the Biden campaign have said that the nominee supports high-performing charter schools. But in a world where fact and fiction are sometimes willfully combined to obscure vital but troublesome details, telling the truth in the clearest terms matters. And that means it’s important for the party’s policy platform to accurately reflect the reality of charter school accountability.

The Cincinnati Enquirer recently published a deeply flawed and misleading “analysis” of the EdChoice scholarship (a.k.a. voucher) program. Rather than apply rigorous social science methods, education reporter Max Londberg simply compares the proficiency rates of district and voucher students on state tests in 2017–18 and 2018–19. Based on his rudimentary number-crunching, the Enquirer’s headline writers arrive at the conclusion that EdChoice delivers “meager results.”

Fair, objective evaluations of individual districts and schools, along with programs such as EdChoice, are always welcome. In fact, we at Fordham published in 2016 a rigorous study of EdChoice by Northwestern University’s David Figlio and Krzysztof Karbownik that examined both the effects of the program on public school performance—vouchers’ competitive effects—and on a small number of its earliest participants. But analyses that twist the numbers and distort reality serve no good. Regrettably, Londberg does just that. Let’s review how.

First, the analysis relies solely on crude comparisons of proficiency rates to make sweeping conclusions about the effectiveness of private schools and EdChoice. In addition to declaring “meager results for Ohio vouchers,” the article states that “private schools mostly failed to meet the academic caliber set by their neighboring public school districts.” No analysis that relies on simple comparisons of proficiency rates can support such dramatic judgments. Proficiency rates do offer an important starting point for analyzing performance, as they gauge where students stand academically at a single point in time. But as reams of education research has pointed out, these rates tend to correlate with students’ socioeconomic backgrounds, meaning that schools serving low-income children typically fare worse on proficiency-based measures. No one, therefore, thinks that it’s fair to assess the “effectiveness” of Cincinnati and the wealthy Indian Hills schools based solely on proficiency data.

To offer a more poverty-neutral evaluation, education researchers turn to student growth measures, known in Ohio as “value-added.” These methods control for socioeconomic influences and give high-poverty schools credit when they help students make academic improvement over time. Thus, by looking only at proficiency, the Enquirer analysis ignores private schools that are helping struggling voucher students catch up. To be fair, Ohio does not publish value-added growth results for voucher students (though it really should). Nevertheless, definitive claims cannot be made about any school or program based on proficiency data alone. It risks labelling schools “failures” when in fact they are very effective at helping low-achieving students learn. Lacking growth data, the Enquirer should have demonstrated more restraint in its conclusions about the quality of the private schools serving voucher students, and the program overall.

Second, the analysis mishandles proficiency rate calculations and skews the results against vouchers. Even granting that proficiency rate comparisons are a possible starting point, Londberg makes a bizarre methodological choice when calculating a voucher proficiency rate. Instead of comparing proficiency rates of district and voucher students from the same district, he calculates a voucher proficiency rate for the private schools located in a district. Because private schools can enroll students from outside the district in which they’re located, his comparison is apples-to-oranges. Londberg’s roundabout method might be justified if the state didn’t report voucher results by students’ home district. The state, however, does this.[1]

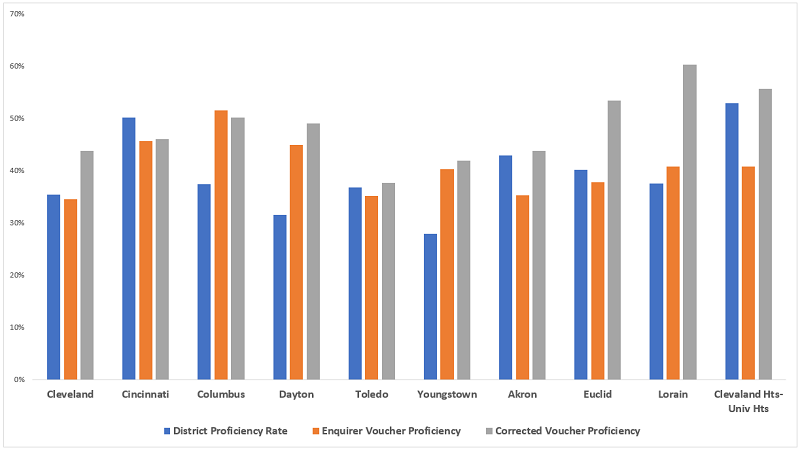

As it turns out, the method matters. Consider how the results change in the districts with the most EdChoice[2] students taking state exams, as illustrated in Figure 1. The gray bars represent a “corrected” calculation of voucher proficiency rates based on pupils’ district of residence. In several districts, the right approach yields noticeably higher rates than what the Enquirer reports (e.g., in Cleveland, Akron, Lorain, and Cleveland Heights-University Heights). In some cases, the correct method changes an apparent voucher disadvantage into an advantage in proficiency relative to the district. For example, vouchers are reported as underperforming compared to the Euclid school district under the Enquirer method. But in reality, Euclid’s voucher students—the kids who actually live there—outperform the district.[3]

Figure 1: Voucher proficiency rates calculated under two methods in the districts with the most EdChoice test-takers, 2017–18 and 2018–19

Notes: The blue and orange bars are based on the Enquirer’s calculations of district and voucher proficiency rates. The gray bars represent my calculations based on the Ohio Department of Education’s proficiency rate data that are reported by voucher students’ home district.

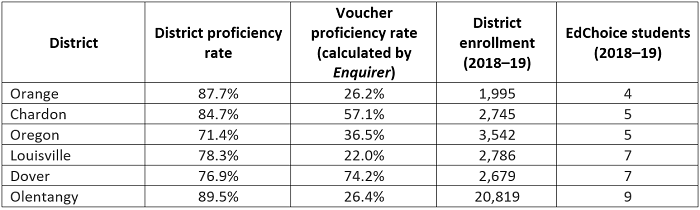

Third, it makes irresponsible comparisons of proficiency rates in districts with just a few voucher students. Due in part to voucher eligibility provisions, some districts (mainly urban and high-poverty) see more extensive usage of vouchers, while others have very minimal participation. In districts with greater voucher participation—places like Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus—it makes some sense to compare proficiency rates (bearing in mind the limitations in point one). It’s less defensible in districts where EdChoice participation is rare to almost non-existent. Londberg, however, includes low-usage districts in his analysis, and Table 1 below illustrates the absurd results that follow. Orange school district, near Cleveland, posts a proficiency rate that is 50 percentage points higher than its voucher proficiency. That’s a big difference. But it’s silly to say that the voucher program isn’t working in Orange on the basis of just a few students. It’s like saying that LeBron James is a terrible basketball player due to one “off night.” Perhaps this small subgroup of students was struggling in the district schools and needed the change of environment offered by EdChoice. Moreover, it’s almost certain that, had more Orange students used a voucher, proficiency rates would have been much closer.

Table 1: District-voucher proficiency rates comparisons in selected districts with few EdChoice students

Note: The Enquirer voucher proficiency rate is based on students attending private schools in that district—it did not report n-counts—not the number of resident students who used an EdChoice voucher (what’s reported in the right-most column above). The EdChoice students in the table above are low-income, as they used the income-based voucher.

Things, alas, go from bad to worse in terms of the results from low-usage districts. In an effort to summarize the statewide results, Londberg states, “In 88 percent of the cities in the analysis, a public district achieved better state testing results than those private schools with an address in the same city.” That statistic is utter nonsense. It treats every district as an equal contributor to the overall result—a simple tally based on whether the district outperformed vouchers—despite widely varying voucher participation. The unfavorable voucher result in Orange, for instance, is given the same weight as the favorable voucher result from a district like Columbus where roughly 5,500 students use EdChoice. That’s hardly an accurate way of depicting the overall performance of EdChoice.

***

Londberg’s amateur analysis of EdChoice belongs in the National Enquirer, not a feature in a well-respected newspaper such as the Cincinnati Enquirer. Unfortunately, however, this piece is sure to be used by voucher critics to attack the program in political debates. As this “analysis” generates discussion, policymakers should bear in mind its vast shortcomings.

[1] A Cleveland Plain Dealer analysis from earlier this year looks at voucher test scores by district of residence.

[2] For Cleveland, the results are based on students receiving the Cleveland Scholarship.

[3] Another oddity of the Enquirer method is that a number of districts with relatively heavy voucher usage are excluded from the analysis. For example, Maple Heights (near Cleveland) and Mount Healthy (near Cincinnati) have fairly large numbers of EdChoice recipients, but they are excluded because there are no private (voucher-accepting) schools located in their borders.

Shortly after Ohio lawmakers enacted a new voucher program in 2005, the state budget office wrote in its fiscal analysis, “The Educational Choice Scholarships are not only intended to offer another route for student success, but also to impel the administration and teaching staff of a failing school building to improve upon their students’ academic performance.” Today, the EdChoice Scholarship Program provides publicly funded vouchers to more than eighteen thousand Buckeye students who were previously assigned to some of the state’s lowest-performing schools, located primarily in low-income urban communities. Yet remarkably little else is known about the program.

Which children are using EdChoice when given the opportunity? Is the initiative faithfully working as its founders intended? Are participating students blossoming academically in their private schools of choice? Does the increased competition associated with EdChoice lead to improvements in the public schools that these kids left?

Fordham’s new study utilizes longitudinal student data from 2003–04 to 2012–13 to answer these and other important questions.

Three key findings:

Dr. David Figlio, Orrington Lunt Professor of Education and Social Policy and of Economics at Northwestern University, led the research.

Arnold Glass and Mengxue Kang, psychology researchers at Rutgers-New Brunswick’s School of Arts and Sciences, are conducting an ongoing study using technology to monitor college students’ academic performance and to assess the effects of new instructional technologies on that performance. Noticing a problematic trend in the data—students’ homework grades far outpacing their exam grades—they have dug into a subset of their findings to try and determine what may be driving that change. The results raise questions about teaching and learning in a time when remote education opportunities are expanding.

The data come from Professor Glass’s own courses: two sections of a lecture course on human learning and memory taught between 2008 and 2011, and two sections of a lecture course on human cognition taught between 2012 and 2018. Glass and Kang analyzed student homework and exam performance (232 total question sets) for 2,433 students who took the classes over the entire period. Fity-nine percent of students were female, and 41 percent were male. The vast majority were between the ages of nineteen and twenty-four.

Homework consisted of online quizzes of four to eight questions posted after each lecture that were to be completed outside of the classroom prior to the next lecture. The students’ answers, the correct answer, and some detail on why the answer was correct were available after the quiz window closed and throughout the semester and were to be used as study guides for the exams. There were three in-class exams given each semester. In the final two years of the study, the researchers also asked students about their process for completing the online quizzes: whether they typically answered from memory (these students were dubbed Homework Generators), or whether they looked up their answers before submitting (dubbed Homework Copiers).

The initial data sorted students into two groups: those whose exam grades were higher than their homework grades and vice versa. The researchers considered the former to be the preferred outcome, since the lectures and online quizzes were intended to build upon one another over the course of the semester and “produce learning” that would ultimately increase the probability that students answered exam questions correctly. This was the predominant pattern shown by the data beginning in 2008. However, the percent of students who exhibited the opposite pattern—scoring better on the online homework than the in-person exams—increased from 14 percent in 2008 to a whopping 55 percent in 2017.

During the most recent two years of the study, Glass and Kang added the survey responses on homework strategy and performed an analysis of variance to discover that Homework Copiers were far more likely than Homework Generators to be among the group whose exam scores lagged their homework scores. In other words, looking up the answer to an online quiz boosted those quiz scores but did not appear to build learning that translated into success on exams when no outside resources could be used. Nearly 60 percent of students reported being Homework Copiers in 2017.

The researchers make a couple of leaps in their discussion of the findings, likely based on other parts of their ongoing research, in which they demonize burgeoning internet access and increasing smartphone usage among students during the ten-year study period. But the survey questions asked here of self-identified Homework Copiers do not differentiate between digital and analog look ups. Whether it’s Google trawling or combing the course’s required textbook for answers, the point is that students are on their own when answering the homework questions. The more common this type of learning becomes—work completed outside of class and without oversight—the more looking up answers will likely occur. It is vital that course design responds to this reality. That college kids are looking up homework answers is probably not big news. That it might undermine their learning and retention when a course is not properly structured to address it should be the headline—or a call to arms. Especially if their little siblings in high schools could be following suit.

SOURCE: Arnold L. Glass and Mengxue Kang, “Fewer students are benefiting from doing their homework: an eleven-year study,” Educational Psychology (August 2020).

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused plenty of problems in education, but a recently published study offers a sliver of good news for schools that—despite recent budget constraints—may soon find themselves in need of additional teachers to make social distancing feasible or to cover the loss of veteran teachers who opt to retire rather than return to the classroom amidst a pandemic.

Harvard professor Martin West and his colleagues begin with a simple question: Do economic recessions, and a tight job market in the broader economy, impact teacher quality? In theory, teaching becomes more attractive to jobseekers during a recession because of the profession’s relative stability; even during economic downturns, teacher pay is rarely cut, schools often continue to hire, and tenure provides job protections that are seldom available in the private sector. Although the comparatively low salaries of teachers might be a deterrence in a healthy economy, downturns could make the classroom more appealing. If that is indeed the case, the average ability of adults entering the teaching force during recessions may also be higher.

The study focuses on Florida, where the state’s certification system includes alternative routes that make it easier for non-education majors to become teachers. The dataset includes approximately 32,600 fourth and fifth grade teachers who started in the classroom between 1969 and 2009, a time span that contained six recessions. Roughly 5,200 teachers entered the profession during one of the recessions. The sample was limited to educators who taught fourth or fifth grade because they typically teach multiple subjects and could be “confidently associated” with student test score gains. The data also included teacher demographics and years of experience, as well as the demographic and educational characteristics of students. To measure teacher effectiveness, the researchers estimated value-added scores based on the math and reading portions of the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test from 2000–01 through 2008–09.

The findings indicate that teachers who started their careers during a recession are more effective at raising student test scores. When compared to those who entered the classroom during better economic times, recession-era teachers registered value-added estimates that were 0.11 standard deviations higher in math and 0.05 standard deviations higher in reading. These are modest effects that translate to no more than a week’s worth of additional learning per year, but the researchers point out that even small differences can add up. It’s important to note that these results were not driven by a specific economic downturn. The recession impact appears over time. The results also do not reflect a difference in observed teacher characteristics or teaching assignments. Instead, it appears that recessions temporarily change the supply of new teachers in positive ways. Furthermore, while they may have been pushed into teaching by temporary economic conditions, the data indicate that many of these teachers opt to stay in the classroom even after economic conditions improved.

Overall, the study offers a silver lining for schools in the age of coronavirus. The current crisis is undoubtedly painful, but it may allow school leaders to hire more effective teachers over the next few years.

SOURCE: Martin R. West, Markus Nagler, and Marc Piopiunik, “Weak Markets, Strong Teachers: Recession at Career Start and Teacher Effectiveness,” Journal of Labor Economics (April 2020).

With widespread school closings, the phrase “we’re all homeschoolers now” has entered our nation’s vocabulary. While many schools are doing their best to continue instruction through online or send-home material, the shutdowns also mean that millions of parents now have new responsibilities for their kids’ learning. (To help in this task, we at Fordham have compiled some of our favorite educational tips and resources, as have others.) With no clear end in sight to the health crisis—and closures during the 2020–21 school year possible as well—parents will likely continue to perform some type of “homeschooling” over the coming weeks and months.

A few commentators have suggested that this experiment in mass homeschooling will inspire more parents to continue this form of education once the crisis passes. Whether that materializes is yet to be seen, but the temporary need to stay home may be putting homeschooling on more parents’ radars. With that in mind, some families may be wondering how to continue at-home instruction, and this piece provides a short primer on Ohio’s homeschooling policies and trends. Note that this piece focuses on “traditional” homeschooling, not online learning via publicly funded virtual charter schools—another form of at-home education. E-school policies are much different and a discussion of them is a topic for another day (see here and here however for more).

Policy

Each state sets its own rules around homeschooling. Some states have tighter requirements, with Ohio being one of the more stringent states in two significant ways. First, Ohio parents must notify their local district that they’re homeschooling, something that several other states don’t require (e.g., Illinois and Michigan). In fact, the Buckeye State has fairly detailed notification rules. Prospective homeschooling parents must submit the following to their home district (among a few other minor items):

The superintendent of a family’s home district reviews these notifications, and he or she may deny a parent’s request to homeschool based on non-compliance with the requirements above. While it’s not clear how often parents’ requests are denied (if ever), state rules detail an appeals process that includes an opportunity to provide more information to the superintendent, and eventually to make an appeal before a county juvenile judge.

The other major requirement that Ohio includes—which a number of other states do not—is testing. To continue homeschooling, parents must submit a yearly assessment report which may be based on: (1) a nationally normed referenced test; (2) a “written narrative” describing a child’s academic progress; or (3) an assessment that is mutually agreed upon by a parent and superintendent. But that’s not all. Should a homeschooling student fail to demonstrate “reasonable academic proficiency,”[1] the superintendent must intervene by requiring parents to submit quarterly reports about instruction and academic progress. If a child continues to fall short, the superintendent may revoke a parent’s right to homeschool their child, though that decision may be appealed to a county juvenile judge.

A few other homeschooling policies of note:

From a compliance standpoint, homeschooling isn’t as easy as simply deciding to stop sending a child to school. Rather, Ohio parents face several procedural steps before they can homeschool. For better or worse, it’s not an entirely permissionless activity. But as the next section indicates, an increasing number of parents are wading through the red tape to homeschool their kids.

Participation

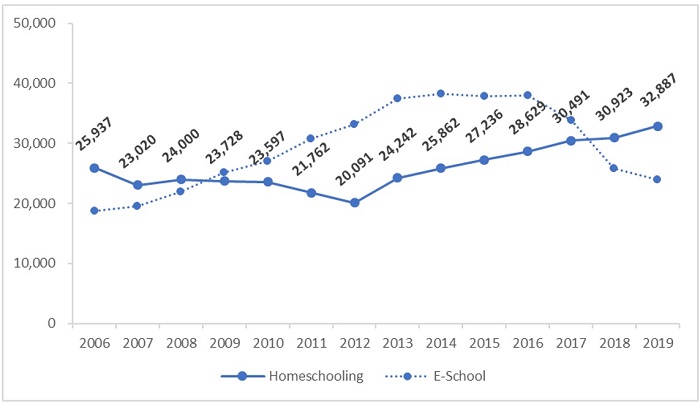

As the chart below indicates, roughly 32,000 students are homeschooled. While that represents a small fraction of all Ohio students (about 1.5 percent), homeschooling numbers have risen since 2012 even as Ohio’s overall school enrollment has declined. A number of factors could explain the uptick. Perhaps the post-recession economic growth has enabled more families to have a stay-at-home parent who can educate their kids. Maybe there’s some increased dissatisfaction with traditional school options (there’s some anecdotal evidence that African American parents are turning to homeschooling as an escape). It’s also possible that the 2013 adoption of a “Tim Tebow law” that permits homeschooled student to participate in district athletics has contributed. The recent declines in online charter enrollment (due largely to the closure of ECOT) might suggest that some former e-school parents are switching to homeschooling. Last, a growing network of supports (co-ops or support groups) and educational resources, including curricula and online materials, may be encouraging more parents take the plunge.

Figure 1: Number of homeschooled students, 2005–06 through 2018–19

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: Online charter school enrollments, another form of at-home learning, are also displayed for context.

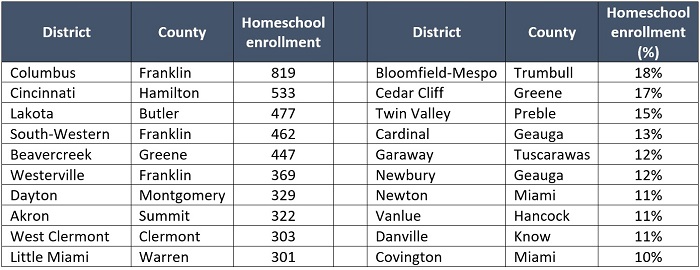

Perhaps in support of the “network” hypothesis are data indicating that homeschooling is more popular in some places than others. The table below displays the top-ten districts with the most homeschooling students, in terms of both absolute numbers (left panel) and as a percentage of district enrollment (right panel). Not surprisingly, we see a mix of larg districts on the left side (mostly urban and suburban). But it’s interesting to note some differences in participation when comparing districts of similar size and demographics. For instance, the suburban Columbus district of Westerville has more homeschoolers (369 students) than the almost equally sized suburban district of Dublin (140 students). Similarly, Cincinnati has far more homeschoolers (533) than Cleveland (140 students). Are those differences due to stronger parent networks? Meanwhile, the right panel shows a number of districts with relatively high shares of homeschooling enrollment. Bloomfield-Mespo, north of Youngstown, leads the state with an 18 percent share and Cedar Cliff (near Dayton) is just behind. Again, it seems plausible to think that the availability of local supports explains the higher percentages of homeschooling.

Table 1: Top homeschooling districts in absolute numbers and as share of district enrollment, 2018–19

Source: For a full listing of homeschool enrollment by school district, see the ODE file “Homeschool Student Data.” Aside from enrollments, no other data on homeschooling students is available via ODE.

***

No school option, whether traditional district, public charter, private, or homeschooling, is the right fit for every family or student. Out of necessity, millions of Ohio parents are experiencing first-hand what homeschooling would be like. For many—likely the vast majority—they’ll come to a deeper appreciation of the hard work their local schools do to serve children. But some might just find themselves attracted to a form of schooling they would’ve never otherwise considered. For these parents, taking a look at the policies and the homeschooling supports in their community would be a good place to start.

[1] This term is only clearly defined in state policy when a norm-referenced test is used (scoring at least 25th percentile).