Ohio is making strides in education-to-workforce pathways

Each year, millions of Americans struggle to navigate the job market. Rapidly changing technology and a volatile economy can make it hard for many workers to find the right fit.

Each year, millions of Americans struggle to navigate the job market. Rapidly changing technology and a volatile economy can make it hard for many workers to find the right fit.

Each year, millions of Americans struggle to navigate the job market. Rapidly changing technology and a volatile economy can make it hard for many workers to find the right fit. ExcelinEd, a national educational advocacy organization, argues that another key difficulty is that many adults lack the skills that employers demand. Educational background, whether it’s a high school diploma or a college degree, doesn’t necessarily translate into a job as the economy and technology change.

High-quality educational pathways that are closely aligned to in-demand, high-wage jobs could help address a lack of readiness. But for many learners, such pathways are difficult to find and even more difficult to access. State policy can fix that, as state leaders are in the best position to connect policies, programs, and institutions across sectors. That’s why ExcelinEd created Pathways Matter, an online tool that outlines a continuum of education-to-workforce policies.

The Pathways Matters framework is divided into six focus areas: learner pathways, postsecondary acceleration, postsecondary credential attainment, workforce readiness, employer engagement, and continuum alignment and quality indicators. Within these areas, there are twenty recommended policies that provide learners of all ages with on and off ramps to high-quality educational pathways. To give state leaders an example of what’s possible—and some tips about where to start—ExcelinEd analyzed the policies of several states.

Ohio was one of these states, and its case study identifies several strengths and weaknesses. We’ll examine the weaknesses in a later piece, but for now, here’s a look at two focus areas where the Buckeye State has made some positive inroads.

Postsecondary acceleration

This focus area homes in on the importance of streamlining postsecondary learning and empowering high school students to earn college credit and reduce the time it will take them to earn a postsecondary degree. Ohio’s current dual-enrollment program, College Credit Plus (CCP), fits that bill, as it allows students in grades 7–12 who have demonstrated academic readiness to take college courses at no cost. The program’s most recent annual report notes that despite pandemic-related disruptions, more than 76,000 students participated in the program during the 2020–21 school year.

But CCP isn’t Ohio’s only postsecondary acceleration initiative. The state also covers the cost of AP and IB exams for eligible low-income students, and state law guarantees that students can receive college credit from state institutions for any available AP test as long as they earn a score of three or higher. Ohio is also home to Career-Technical Assurance Guides, which are statewide articulation agreements that require all public colleges and universities to award postsecondary credit for certain career and technical education (CTE) courses. Not every available CTE course is included in these guides, but there are a wide variety of options, and their existence ensures that courses of all types—not just typical academic subjects—can translate into college credit.

Workforce readiness

This focus area emphasizes the importance of ensuring that the skills Ohioans are taught, the credentials they earn, and the work-based learning opportunities that are available will effectively prepare them for the future. Ohio still has some work to do in this area, but the state has made some big strides. Consider the following:

***

If Ohio wants a strong and vibrant workforce, it’s crucial that learners of all ages are well-prepared. Effective state policy that bridges the K–12, higher ed, and workforce sectors is crucial, and the Pathways Matter framework offers some solid policy recommendations for how to get it done. Ohio already has several of these policies in place, especially in the postsecondary acceleration and workforce readiness areas. State leaders deserve kudos for these efforts. But there’s still plenty of work to be done, so stay tuned for an analysis of Ohio’s areas for growth.

In 2015, federal lawmakers passed the Every Student Succeeds Act, or ESSA, the main K–12 education law of the land. Under this statute, states must submit an “ESSA plan” that describes how they intend to implement the provisions. In 2018, the U.S. Department of Education approved Ohio’s original ESSA plan, but due largely to last year’s changes to school report cards, the document needs an update. Earlier this month, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) released a draft amendment for public review and comment. Federal approval of the report card changes to the plan should be no more than a formality, as the state’s legislative overhaul adheres with ESSA.

In addition to report cards, ESSA also requires states to identify and oversee improvement activities in low-performing schools. Under federal law, Ohio must identify its lowest 5 percent of Title I public schools and those with four-year graduation rates below 67 percent. Such schools are in “comprehensive support and improvement,” or CSI, status.

While the identification criteria are set in federal statute, states are tasked with creating their own “exit criteria” that CSI schools must achieve to be released from state oversight. ODE establishes them via its ESSA plan, as neither Ohio law nor State Board of Education regulations contain such criteria.

Getting these criteria right is important. To drive student learning, they should set a reasonably high bar before schools are removed from state supervision. The state should also require improvements large enough to help guard against situations in which CSI schools meet the criteria and exit, only to be re-identified again as an underperformer shortly thereafter (akin to educational “recidivism”). Last, schools should know what exactly the state’s improvement expectations are, and there should be no question about whether a school has or has not met the requirements.

Though never implemented due to Covid waivers, the original exit criteria in Ohio’s ESSA plan left open questions about how they’d work in practice. In its draft amendment, the agency proposes a rewrite, but they still need more work. Here’s the proposal (emphasis mine):

The exit criteria for CSI schools will be based on the revised report card measures. Schools are expected to meet the exit criteria within three years. When determining which schools are eligible to exit CSI status, each school’s improvement will be measured against its achievement level in the year that it was identified as a CSI school to ensure that the improvement is substantial and sustained. The exit criteria include:

• School performance is higher than the lowest 5 percent of schools based on the ranking of the Ohio School Report Card overall ratings for two consecutive years;

• The school earns a federal graduation rate of better than 67 percent for two consecutive school years;

• In the second year of meeting the two above criteria, the school also demonstrates improvement on overall rating assigned on the Ohio School Report Cards.

The bold text is absolutely crucial. ODE is right to insist that CSI schools make “substantial” and “sustained” improvement. But it’s not clear that the bulleted exit criteria meet those standards. And depending on how the third criterion is interpreted, it could directly conflict with the bolded language. Let’s take a closer look.

Criterion 1: Overall rating score above the lowest 5 percent.[1] The two-consecutive-year requirement seems to meet the “sustained” standard, but CSI schools could be in the 6th percentile in overall ratings and still meet this threshold. In such cases, that is hardly a “substantial” improvement, and schools could easily relapse into CSI status.

Criterion 2: Graduation rate above 67 percent. Again, the two-consecutive-year requirement is good, but CSI schools could register small improvements (e.g., moving from a 65 to 68 percent graduation rate) and meet this criterion.

Criterion 3: Higher overall rating. The third criterion appears to be an effort to ensure that CSI schools do more than just avoid the woeful performance that led to identification to exit. But the language is problematic. Does a CSI school need to achieve a higher rating compared to the year immediately prior or the year of identification—which is at least two years back?

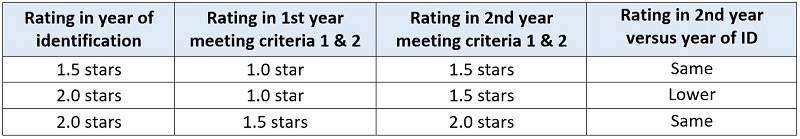

If the idea is to compare ratings to the year prior, problems could arise. The table below shows three examples in which a school would achieve higher ratings versus the year prior while not improving against the baseline identification year. This would conflict with the bolded provision that requires a school show improvement relative to the year of identification.

Note: Criteria 1 and 2 refer to having an overall rating score above the lowest 5 percent and a graduation rate above 67 percent. Ohio’s new rating system uses five-star ratings, with half-star increments.

Of course, this could also refer to higher ratings versus the year of identification. If that’s the case, how does this work for current CSI schools whose overall ratings were letter grades in 2017–18—their year of identification—instead of the state’s new star system? And regardless of the base year, there are two additional issues with this criterion. First, it doesn’t say how much improvement is required. (Does a half-star improvement count?) Second, it falls short of the “sustained” standard because it requires just a single year of higher ratings.

* * *

The exit criteria are still a mush. My solution is this: Before submission, ODE should revise criteria one and two to make them more challenging, and should scratch the third. Specifically, below is how I would write the exit criteria based on ODE’s proposed ESSA plan amendment with my revisions in red. Because criterion one would set a higher bar for overall improvement—under the assumption that ODE is intending to rank CSI schools against Title I schools—schools meeting this target would likely post a higher overall rating, as well. Thus, the last criterion could be dropped to avoid unnecessary complication.

Criterion 1: School performance is higher than the lowest 5 10 percent of Title I schools based on the ranking of the Ohio School Report Card overall ratings for two consecutive years; and (if applicable to a school)

Criterion 2: The school earns a federal graduation rate of better than 67 75 percent for two consecutive school years.

Criterion3: In the second year of meeting the two above criteria, the school also demonstrates improvement on overall rating assigned on the Ohio School Report Cards.

To be sure, ironing out the state’s exit criteria only scratches the surface of Ohio’s school improvement policies. But making sure these rules are clear, consistent, and more rigorous is a basic first step.

[1] As written, it’s hard to tell whether the idea is to mirror exactly the ESSA identification criteria—score above the lowest 5 percent of Title I schools—or is truly intended to require schools to score above the lowest 5 percent of all public schools (which would be a higher bar).

Last week, the Ohio Senate Primary and Secondary Education committee passed a provision that would weaken the state’s charter sponsor evaluation system. The language, one of a plethora of amendments added to House Bill 583, would allow a sponsor to receive an “effective” rating even if it receives zero points—completely fails—one of the three components of the evaluation system. If the amendment goes through, it would reverse course on one of the reforms that has greatly strengthened charter accountability in Ohio.

Sponsors (a.k.a. “authorizers”) are the entities that permit public charter schools to open and oversee schools’ performance. They make high-stakes decisions about whether schools are allowed to remain in operation or must close due to poor performance and other factors. While their role often flies under the radar, sponsors are critical gatekeepers for charter school quality.

Concerned about the rigor of sponsors’ oversight, Ohio lawmakers wisely implemented reforms during the 2010s that incentivized them to focus on best practices and the academic outcomes of their schools. The stronger sponsor accountability system has undoubtedly contributed to the closure of dozens of low-performing schools and is a key factor in the recent improvement in Ohio’s charter sector. The centerpiece of these accountability efforts is a sponsor evaluation system—with teeth. It has three equally weighted components, each of which is scored on a scale of zero to four points:

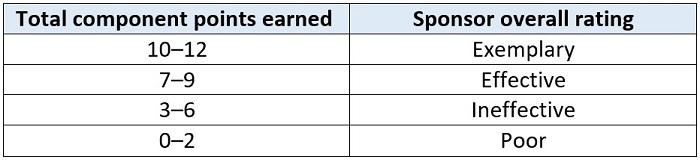

The component scores yield a total score that is translated into an overall sponsor rating (Table 1).

Table 1: How component points are translated into an overall sponsor rating

The overall ratings have implications. Sponsors receiving top marks earn exemptions outlined in the statute, such as less frequent evaluation and the removal of caps on the number of schools they can authorize. On the other hand, sponsors receiving the lowest two ratings are subject to sanctions, including a freeze on approving additional schools and revocation of sponsorship authority for either a poor rating or three straight ineffective ratings.

State law directs the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) to iron out the finer details of the evaluation system. Such decisions include crafting the rubric for assessing quality sponsorship practices and setting the overall “grading scales,” as shown in Table 1. In its rating system, ODE also includes a mechanism that assigns ineffective ratings to sponsors that receive zero points in any of the three components, even if their total points earned initially generate a higher mark.

Maintaining this demotion mechanism—which the HB 583 amendment would eliminate—is critically important. It goes without saying that a zero on any of the three components is deeply alarming. There is something seriously wrong if a sponsor is neglecting state laws or failing to meet basic authorizing standards.

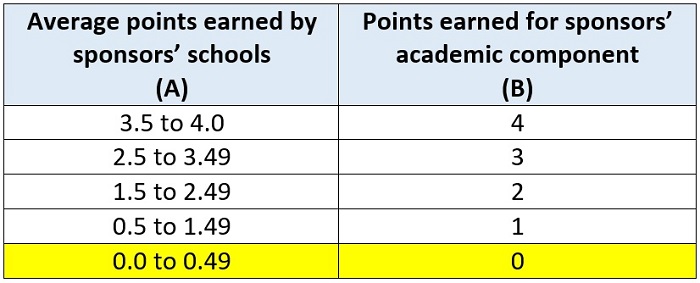

But it’s especially disturbing if sponsors are choosing to authorize dysfunctional schools that are poorly serving students. That’s exactly what happens when sponsors receive zero academic points. In the evaluation system, schools rated 1 or 1.5 stars (i.e., F’s) generate zero points for sponsors, 2- and 2.5-star schools produce one point, and so on. Sponsors whose schools produce an average of 0 to 0.49 points receive zeros on the academic component. To receive so few points, the lion’s share of a sponsor’s portfolio would need to be extremely low-performing.

Table 2: How sponsors receive academic component scores

Note: ODE first calculates the average (weighted by school enrollment) points earned by all schools in a sponsor’s portfolio (column A). That point total is then translated into a score of 0 to 4 for a sponsor’s academic component (column B).

Given the abysmal performance needed to generate a zero on academics, only a few sponsors have done so. In 2018–19—the last year sponsors received academic ratings—three of the state’s twenty-five sponsors received zeros for the component. Combined, the three sponsors authorized eight schools, five of which received F’s that year. In 2017–18, no sponsors received zero academic points.

The upshot is this: If the HB 583 amendment goes through, a sponsor could be authorizing failing schools and get a passing mark just by doing its paperwork correctly. But the state shouldn’t turn a blind eye to poor academics. As the bill goes through the finalizing process, legislators should drop the sponsor evaluation amendment. They’ve worked too hard to improve Ohio’s charter school sector to back off now.

Successful school choice requires that parents have ample access to high-quality information. Even though choices made might not fully accord with easily observable data, parents want—and deserve—as much detail on available schools as possible. Research can help determine the most influential types of information and the preferred formatting and delivery of it. That’s the case with a new paper by Jon Valant of the Brookings Institution and Lindsay H. Weixler of Tulane University.

In New Orleans, families choose schools via the city’s central OneApp system and can rank order up to twelve choices per child. Valant and Weixler’s study focuses on families choosing pre-K, kindergarten, and ninth grade slots, the primary entry points for students heading to a new school. Before families requested placements for the 2019–20 school year, they were randomly assigned to one of three groups: a “growth” group, which received information from the researchers on the highest-performing schools they could request, regardless of distance from home; a “distance” group, which received information on all of the schools available near them, regardless of ranking; and a control group, which received communications that did not highlight any particular schools. All families, regardless of group, received this information via mailed flyers, text messages, and emails.

Academic performance information for K–12 schools came via a new state ranking system focusing on academic growth measures; for pre-K programs, a statewide early childhood education scoring system—also new that year—was utilized. The researchers note that providing the list of nearby schools is not an idle effort. Unlike many other cities where school options can be static for years, New Orleans annually sees many new schools open, old schools close, and some existing schools relocate. In theory, nearly all public schools and a large proportion of private schools anywhere in the city are available to any family.

Now for the results. The information provided to families on high-performing schools led to a 2.7 percentage point increase in the probability of growth group students requesting at least one high-growth school compared to the control group. It also led applicants to request .09 more high-growth schools on average and to request .2 more schools overall. These effects were driven almost exclusively by students entering ninth grade.

By contrast, there was little observed impact of providing location information to the distance group as a whole, who did not exhibit a statistically significant difference in requesting a nearby school, though kindergarten students were significantly more likely to choose a nearby school that the researchers advertised to them.

Among student subgroups, only one impact stood out, but it was significant: Students with disabilities receiving the growth treatment were 15.5 percentage points more likely to request at least one high-growth school than their control group counterparts. Those students also requested 1.6 more schools overall and requested an additional 0.5 high-growth schools on average.

Not for the first time, a randomized control trial has found that parents pay attention to—and respond to—school information provided to them when they have options from which to choose. As important as this knowledge is, such research designs remain idealized situations, even when real parents are involved. Valant and Weixler note in their analysis that they have no way of knowing what information parents was actually seen by parents—including their own—or sought out from other sources. Additionally, transportation and other barriers, school type, and school culture all can loom large in school choice decisions and are largely unanalyzed in research. Most importantly, this research does not include data on which schools were offered by the algorithm or which ones were ultimately chosen by families. Some researchers are getting closer to understanding actual choices, finding that parental calculus is complex, but there are so many more variables to assess than the typical research design can accommodate.

SOURCE: Jon Valant and Lindsay H. Weixler, “Informing School-Choosing Families About Their Options: A Field Experiment From New Orleans,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (May 2022).

NOTE: On May 24, 2022, the Ohio House of Representatives’ Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on a bill to eliminate a key aspect of state’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee. Fordham’s vice president for Ohio policy provided testimony against this effort. These are his written remarks.

Reading is absolutely essential for functioning in today’s society. Job applications, financial documents, and instruction manuals all require basic literacy. And all of our lives are greatly enriched when we can effortlessly read novels, magazines, and the daily papers. Unfortunately, even today, roughly 43 million American adults—about one in five—have poor reading skills. Of those, 16 million are functionally illiterate.

Giving children foundational reading skills, so they can be strong, lifelong readers, is job number one for elementary schools. Understanding this, Ohio passed the Third Grade Reading Guarantee in 2012. The law’s aim is to ensure that all children read fluently by the end of third grade—often considered the point when students transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.”

The Guarantee takes a multi-faceted approach. It calls for annual diagnostic testing in grades K-3 to screen for reading deficiencies and requires reading improvement plans and parental notification for any child struggling to read. Importantly, it also requires schools to hold back third graders who do not meet state reading standards and to provide them with additional time and supports.

I urge the committee to reconsider the elimination of the guarantee’s retention requirement as proposed in HB 497.

The goal of retention is to slow the grade-promotion process and give struggling readers more time and supports. When students are rushed through without the knowledge and skills needed for the next step, they pay the price later in life. As they become older, many of them will decide that school is not worth the frustration and make the decision to drop out.

An influential national study from the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that third graders who did not read proficiently were four times more likely to drop out of high school. A longitudinal analysis using Ohio data on third graders found strikingly similar results. The consequences of dropping out are well-documented: higher rates of unemployment, lower lifetime wages, and an increased likelihood of being involved in the criminal justice system.

Seeing data such as these, almost everyone agrees today that early interventions are critical to getting children on-track before it’s too late.

Some believe that schools will retain children without a state requirement. Anything’s possible, but data prior to the Reading Guarantee makes clear that retention was exceedingly rare in Ohio. From 2000 to 2010, schools retained less than 1.5 percent of third graders. Retention has become more common under the guarantee, as about 5 percent of third graders were held back in 2018-19. As a result, more students today are getting the extra help they need.

Make no mistake, if HB 497 passes, Ohio will in all likelihood revert to “social promotion.” Students will be moved to the next grade even if they cannot read proficiently and are unprepared for the more difficult material that comes next. There will be relief in the short-run but the price in the long term will be significant.

Data and research

Shifting gears, I’d like to briefly address two claims that have come up in committee hearings related to data and research.

First, some have claimed, based on research studies, that holding back students can have adverse impacts. There is some debate in academic circles about how to assess the impacts of retention. Doing a gold-standard “experiment” with a proper control group is not possible in this situation, so scholars rely on statistical methods that help make apples-to-apples comparisons between similar children. But unless researchers use very careful methods, the results don’t give us much insight.

Arguably, the best available evidence on third-grade retention—as opposed to retention generally—comes from Florida, which has a similar policy to Ohio’s reading guarantee. That analysis, which compared extremely similar students on both sides of the state’s retention threshold, found increased achievement for retained third graders on math and reading exams in the years after being held back. It also found that retained third graders were less likely to need remedial high school coursework and posted higher GPAs. The analysis found no effect, either positively or negatively, on graduation.

If you’d like to review this research for yourself, an essay on the findings by Harvard University’s Martin West, who led the Florida study, was published by the Brookings Institution in 2012. The longer, academic report was published by the National Bureau of Economic Research and in the Journal of Public Economics in 2017.

The second claim, particular to Ohio, is that the reading guarantee isn’t producing the improvements we’d like to see. The basis is a paper from The Ohio State University’s Crane Center that notes flat 4th grade reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress from 2013-17. NAEP does offer a useful high-level overview of achievement, but raw trend data are not causal evidence about the impact of the third grade reading guarantee—or any other particular program or policy. The patterns could be related to any number of factors that affect student performance, whether economic conditions, demographic shifts, school funding levels, and much more. Without any statistical controls, it’s impossible to isolate the effect of the reading guarantee.

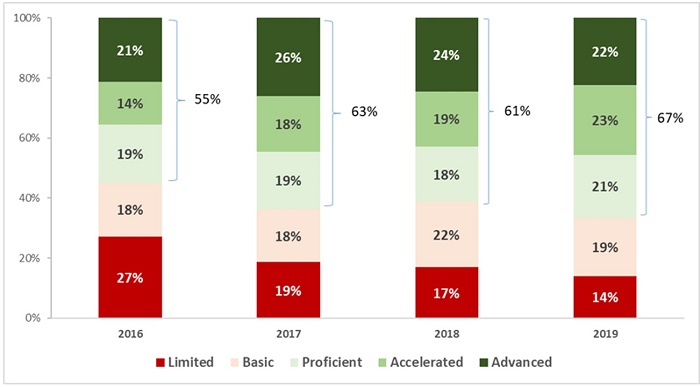

Of course, NAEP isn’t the only yardstick. It’s also worth considering what state testing data show. The chart below shows third grade ELA scores in Ohio. We see an uptick in proficiency rates—from 55 percent in 2015-16 to 67 percent in 2018-19. Also noteworthy, given the guarantee’s focus on struggling readers, is the substantial decline in students scoring at the lowest achievement level. Twenty-seven percent of Ohio third graders performed at the limited level in 2015-16, while roughly half that percentage did so in 2018-19.

Ohio’s third grade ELA scores, 2015-16 to 2018-19

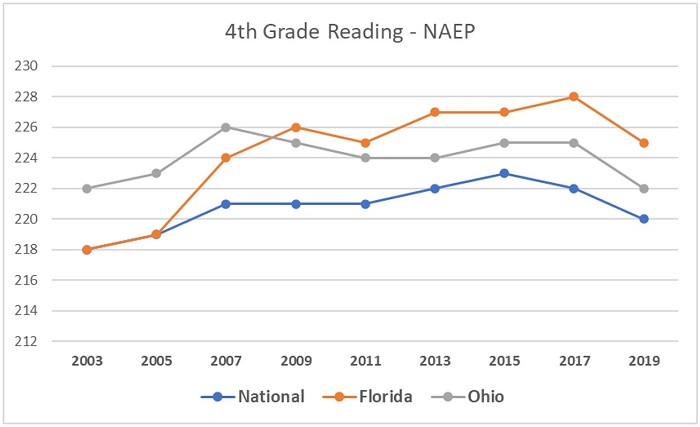

Florida began in 2003 well below Ohio on the NAEP fourth grade reading assessment. By 2019, the Sunshine State was five points—generally seen as half a grade level—above Ohio. Not shown on this chart, the improvements were driven by increased achievement by low-income and Black students.

Much like NAEP trends, this shouldn’t be construed as causal evidence. But the improvements on third grade state exams should be weighed heavily in any analysis on whether the guarantee is improving literacy across Ohio.

Right now, no rigorous evaluation of Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee and the retention requirement has been conducted; however, the structure of Ohio’s law and the strong data system in place lends itself to a high quality research design. We encourage this committee to request that the Ohio Department of Education conduct a study on this issue before taking action on ending the retention requirement.

The best evidence we have on the impact this policy could have long term is from states like Florida that have rigorously implemented early literacy policies. Again, it’s always hard to say NAEP is causal, but the chart below is certainly impressive.

Note: Florida enacted its reading guarantee in 2002; Ohio enacted its guarantee in 2012. NAEP is given every two years in grades 4 and 8, math and reading, but the 2021 cycle was delayed due to Covid.

* * *

Ten years ago, Ohio lawmakers decided it would be better to intervene early than have students suffer the consequences later in life. The logic made sense then, and we believe that it’s still true today. Of course, retention—like any policy—isn’t a silver bullet. It must be paired with effective supports, and students need to continue receiving solid instruction in middle and high school. What the policy does, however, is slow the promotional train and give struggling readers more attention and opportunity to catch up.

Thank you for the opportunity to offer testimony, and I look forward to any questions that you may have.