Governor DeWine is right: Ohio must not fail its students

At this point, it’s common knowledge that Covid-related school closures are having a major impact on students. Absenteeism rates are high.

At this point, it’s common knowledge that Covid-related school closures are having a major impact on students. Absenteeism rates are high.

At this point, it’s common knowledge that Covid-related school closures are having a major impact on students. Absenteeism rates are high. Parents and teachers are rightly concerned about students’ mental health. And, of course, learning loss abounds.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Governor DeWine is calling for all hands on deck. Earlier this week, he announced that Ohio public schools must come up with plans to address unfinished learning and submit them to the state by April 1. “How do we help the kids who have fallen farther behind because of the pandemic?” the governor asked during his announcement. “We simply cannot fail these children.”

The governor is right, and his administration deserves praise for making student learning a priority. Here are four reasons why this approach is the right move:

It puts students first. Learning loss isn’t something we can just wave away as another casualty of the pandemic, like cancelled concerts or family gatherings. The content and skills that students are missing out on are necessary, and schools have a professional responsibility and a moral obligation to make sure students get caught up. If they don’t, students’ struggles will only worsen after the pandemic.

It leverages resources. Ohio schools have $2 billion coming their way thanks to the federal relief package passed in December. The state budget is still in the works, but the governor’s proposal includes a whopping $1.1 billion for student wellness programs and services. Between these and other funding infusions, schools should be on a solid financial footing. Asking them to create plans to put these dollars to good use is not only fair, it’s essential.

It offers flexibility to develop local solutions. The governor could have bypassed local leaders and worked with the legislature to come up with a mandate for how schools must address learning loss. Instead, he chose to respect the knowledge and expertise of district leadership, teachers, and communities and gave them the freedom to craft plans that address the unique needs of their students. He provided examples of research-backed interventions such as summer school, tutoring, and extended learning time that schools would be wise to consider. But at the end of the day, what they choose to do is up to them.

It makes educational recovery an urgent priority. The April 1 deadline is a month and a half away. That isn’t a ton of time, but we can’t afford to stretch out the deadline any further. Learning losses will only increase the longer schools wait to take action. The upcoming summer months are a perfect opportunity to give kids back some of the time they lost, and using that time effectively means starting the planning process now. As State Superintendent Paolo DeMaria noted, most districts are already working to address unfinished learning. All the governor is asking is that they submit those ideas so that his administration and the legislature can work together on making changes to support schools in their efforts.

Without a doubt, the next few months will be just as hard as the last. But thousands of teachers have been—or will soon be—vaccinated, and there’s light at the end of the tunnel. Now is the time to start planning how we’ll mitigate all the learning losses our students have suffered over the course of the pandemic. Kudos to Governor DeWine for making this a priority.

Interdistrict open enrollment, one of the longest running and most popular forms of school choice, unlocks public school options for more than 80,000 Ohio students. It allows children to attend school in a district other than the one they live in. Under current state policy, district participation in open enrollment is voluntary. Most districts choose to participate, but this year 107 of Ohio’s 608 school districts decided to keep their schools closed to nonresidents, a similar number to previous years.

Here at Fordham, we’ve consistently urged Ohio lawmakers to require all traditional school districts to admit non-resident students. This would increase public school opportunities for students who reside in Ohio’s urban centers, as most non-participating districts surround big cities such as Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Columbus. It would also be more consistent with the state’s approach to public charter schools, which generally must be open to all comers.

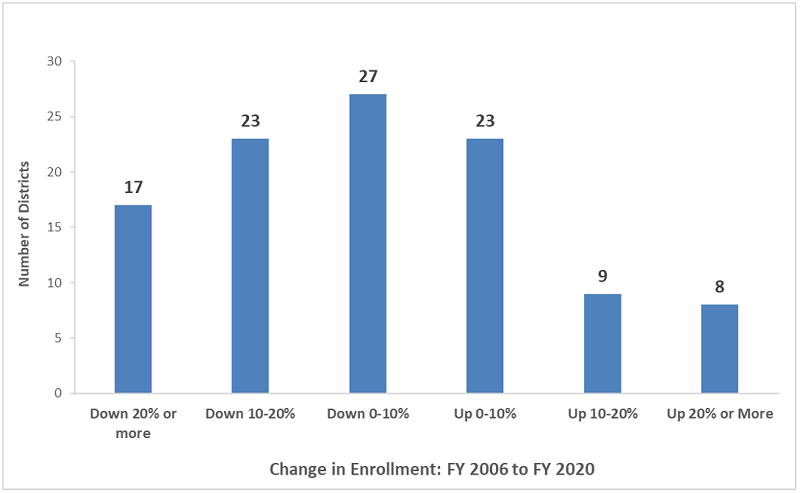

Yet one potential difficulty, which we’ve acknowledged in our recommendations, is that districts might be at capacity, with no room in existing schools or classrooms for more children. In those cases, onboarding additional students would pose significant challenges. But are capacity constraints keeping districts from participating? Though no central database reports schools’ building capacities, we can look at enrollment trends to get a general sense of it. This isn’t a perfect method: districts with declining enrollment might have gone from 110 percent capacity to 105 percent, for example, and we would not know it. Still, it’s fair to assume that, in most places, declining enrollment implies that extra seats are available.

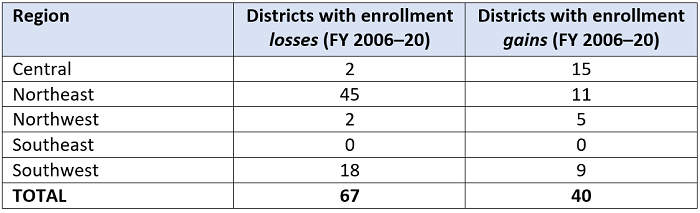

Lo and behold, as figure 1 shows, a large majority of non-participating districts have lost students. From 2006 to 2020, sixty-seven of these 107 districts experienced enrollment losses. Forty of these districts lost 10 percent of students or more. (Though not displayed below, the results are similar when FY 2010 is the baseline year—seventy districts lost enrollment—and about half saw enrollment declines if FY 2015 is the baseline.) Note that these enrollment changes were not affected by the pandemic-related declines seen in the FY 2021 data.

Figure 1: Enrollment trend among Ohio districts that do not participate in open enrollment, 2005–06 to 2019–20

Source: Ohio Department of Education, Open Enrollment and District Report Cards

Following broader demographic trends within Ohio, most of the shrinking non-participating districts are located in northeast Ohio, while those gaining enrollment are in the fast-growing central Ohio suburbs around Columbus. Table 1 displays the data by region.

Table 1: Geographic analysis of districts that do not participate in open enrollment

Note: School districts were linked to a region based on the Ohio Department of Natural Resources’ division of the state.

Thus we see that most non-participating districts probably have excess capacity. There’s no good reason for these districts to refuse admission to non-resident students. Even the economics of open-enrolling students makes sense. The state provides an additional $6,020 for each student who open-enrolls (receiving districts may receive extra funds for students with disabilities). Because the district has capacity, the dollars tied to an additional student should cover the incremental costs of her education. True, a district may need to purchase another textbook or two, but its facility, administrative, and instructional costs wouldn’t rise significantly by filling an open seat. Airlines don’t turn away travelers when their planes are half-full. Schools shouldn’t either.

The story is more complicated for fast-growing districts. They are likely being stretched to meet the needs of resident students (though falling birthrates and shifting enrollment in the wake of the pandemic may soon yield excess capacity). Nevertheless, to address these outliers, state legislators should consider a capacity-based exemption in a switch to a mandatory open-enrollment system. But how should they design such an exemption? The capacity provisions from other states with mandatory open-enrollment laws offer a few ideas that could guide Ohio:

It’s sad to see school districts with plenty of capacity refuse to open their doors to non-resident students. The reasons behind their refusals are not altogether clear (one suspects some form of “nimbyism” or worse), but closed districts actively deny thousands of Ohio students an opportunity to attend a school that better meets their needs. State lawmakers should step in to rectify this situation by requiring all districts with capacity in their schools to participate in open enrollment.

It’s no secret that the pandemic has been extraordinarily difficult on education. Reopening decisions, complex in-person safety protocols, virtual school, and the specter of learning loss have made the past year tough. The pandemic’s most significant long-term impacts, though, likely won’t be felt by the students participating in a variety of virtual, hybrid, and in-person school. Instead, they will be felt by the millions of U.S. students who didn’t participate at all.

The troubling number of students who have gone “missing”—those who aren’t showing up for school every day, whether in-person or online—has been well-documented. This summer, the American Institutes for Research published the results of a survey sent to 2,500 traditional districts and 250 charter management organizations across the county. Most schools reported that they were monitoring student participation, but the gaps between high-poverty and low-poverty districts were troubling. For example, while 61 percent of low-poverty districts reported monitoring student logins to online programs that were being used by the district, only 45 percent of high-poverty districts did the same.

Absenteeism also appears to be disproportionately high among the most disadvantaged groups of students. An analysis completed by Bellwether estimates that approximately three million educationally marginalized students—those who are in foster care or experiencing homelessness, students with disabilities, English language learners, and migrant students—may not have experienced any type of formal education since March of 2020. State-specific data show similar results. Connecticut, for instance, has found “substantially lower levels of attendance among vulnerable student populations including Black and Hispanic/Latinx students, English language learners, students with high needs and disabilities, and those living in poverty and experiencing homelessness.”

Which brings us to Ohio. In mid-December, Patrick O’Donnell published a stunning piece about absenteeism rates in Cleveland. It seems that in Ohio’s second largest school district, thousands of students have been missing from school since the pandemic started. Yes, thousands.

The explanation behind the Cleveland absences varies. Approximately 1,500 students who are old enough to be in pre-K or kindergarten were never enrolled by their parents. Similar numbers are showing up in other Ohio districts, as parents opt to hold their children back a year rather than start school in the middle of a pandemic. A few hundred additional students transferred to schools outside the district, like charters or private schools. But the vast majority of missing students—a whopping 6,000 or so kids, or nearly 16 percent of the total student population during the 2018–19 school year—are still enrolled in the district but aren’t showing up for virtual class.

To be clear, this isn’t a Cleveland-specific issue. Plenty of other Ohio districts are also struggling. It should also go without saying that the stakes are high. Research is clear that chronic absenteeism has an academic cost and an economic one. A recent study from the University of California also indicates that increased absenteeism harms students’ social and emotional development. All things considered, it seems apparent that state and local leaders need to do something.

Fortunately, Ohio has a unique opportunity to tackle the issue head on thanks to Student Wellness and Success funding. This is a statewide initiative aimed at improving student wellness and success by addressing non-academic needs. The initiative was first introduced by Governor DeWine in his 2019 budget, which allocated $675 million to public schools, awarded on a per-pupil basis over two years.

It’s still early in the 2021 budget cycle, but the governor’s newly proposed budget includes a whopping $1.1 billion over the next biennium to continue the initiative. Assuming the program doesn’t change much, one of the allowable areas under law—family engagement and support services—could cover a massive effort by districts and schools to locate missing students and get them re-enrolled and re-engaged in school.

Obviously, such efforts should be driven by local needs and local leaders. But schools need support from the state to make it happen, and that includes funding—which they’ll have plenty of if the General Assembly approves this second round of dollars. Districts could use their funds to hire additional staff to track down missing students and connect their families with the resources they need to get kids back in school and back on track. Schools could also hire a team of counselors and mentors to check in on students and make sure they stay on track, as mentoring programs are an allowable use of funds under current law. Between the influx of federal funds coming Ohio’s way and the fact that student wellness funding can be used to provide services prior to and after regularly scheduled school days, schools could also implement programs specifically designed to serve students who missed a ton of time and need help catching up.

The possibilities are endless. But one thing’s for sure: State and local leaders need to track down and support the students who have gone missing during this pandemic, and they need to do it fast. Student Wellness and Success funding could be a key part of those efforts.

Earlier this week, Governor Mike DeWine unveiled his state budget for fiscal years 2022 and 2023. At the macro level, it assumes stable to modestly growing tax revenues over the next two years, an important assumption given the serious concerns that many have raised about deteriorating state finances amid the pandemic. The positive revenue outlook allowed the governor to propose increasing state funding for K–12 education from $7.9 billion this year (FY 2021) to $8.2 billion in FY 2022—a 3.2 percent bump. Spending is virtually unchanged for the second year of the biennium. Note that these figures exclude additional federal funds that Ohio receives for K–12 education, including the massive amount of Covid-related emergency aid, along with billions in local dollars raised by school districts.

Besides its encouraging totals, DeWine’s budget includes some important proposals for primary–secondary education. Noteworthy throughout is the governor’s constancy, visible in his continuing commitment to programs that he shepherded through the legislature during his first budget. In an age when almost everybody’s policies and priorities seem to be in constant flux, it’s commendable to see the governor stay the course—even doubling down as we’ll see—on what he believes are vital initiatives that benefit Ohio students. Consider the following:

Those are a few of the many important items in the governor’s budget. (For a more extended discussion about the budget with my Fordham colleagues, check out this video recording.) There’s one major omission, however: no school funding formula. As in his first budget, DeWine again refrained from putting forward a new formula for how state education dollars are allocated across Ohio school districts Instead, DeWine’s proposal would once again suspend the existing formula—it’s been frozen for FYs 2020–21—thereby essentially funding districts based on their 2019 state allotments, the last year in which Ohio used a formula to fund schools.

To be fair, the governor and his hard-working team have a great deal on their plate. It would’ve done more harm than good to propose an ill-conceived formula. What this means, however, is that onus is now on the General Assembly to decide on a funding formula for FYs 2022–23. Will legislators agree to the House’s much-discussed Cupp-Patterson funding model, which has strengths, weaknesses, and, if fully implemented, would be incredibly expensive? Will the Senate set forth its own funding plan when the budget bill reaches it? Or will the General Assembly simply restart the formula in statute by using the existing framework and applying updated district enrollment and wealth data?

It’s way too early to know how this will play out. But one thing is clear: Ohio shouldn’t keep funding education based on old and outdated information. Continuing to suspend the formula, as if time stands still and nothing changes, isn’t fair to students, schools, or taxpayers. Instead, to ensure that students are properly funded based on where they currently attend school, the legislature will need to settle on a formula—and actually use it—whether that’s the existing one or an overhauled model.

Overall, there’s much to like about the new DeWine budget. With any luck, Senate and House lawmakers will agree that student wellness, career-technical education, and quality charters are worth keeping—and multiplying. But there’s still work to be done, especially around the basic school funding formula. How will it all shake out? Stay tuned to the Ohio Gadfly in the coming weeks as we track—and comment on—all the latest twists and turns.

Budget season in Ohio is always fraught, but factor in the pandemic and accompanying economic downturn and we can be sure that the next few months will be even more heated than usual. Ohioans should expect plenty of education-related proposals in the mix. But will any of them be bold enough to mitigate widespread learning loss and get schools onto a better path than the one they traveled before the pandemic? How can we possibly sort through dozens of ideas in a quick but effective manner? The answer just might be found in an unexpected place—the familiar party game Kiss, Marry, Kill.

For readers unaware, the basic purpose of the game is simple. Participants are presented with an option—perhaps a Disney prince or a Marvel superhero—and they have to decide whether to kiss (temporarily choose), marry (permanently choose), or kill (permanently get rid of) that individual.

It might seem frivolous as commonly played, but this game is actually not a bad method for quickly sorting through a mountain of policy ideas. If Ohio lawmakers are serious about making up for learning loss, they need to act fast. Budget season offers a solid opportunity to put in place temporary and permanent policies, as well as a chance to do away with what’s not working, all in the name of serving kids well. But which policies should be kissed, married, or killed? Here’s my take.

Kiss: Intensive, state-funded summer school and bridge camps

The best way to make up for all the learning time lost during this pandemic is to provide students with plenty of additional time. Capitalizing on the summer break is critical, and Tennessee lawmakers recently passed a bill that offers an excellent model. Ohio lawmakers should use it as the basis for our own two-pronged approach to extending learning time.

Intensive summer school should be funded by the state, implemented by districts, and aimed at students who have been the most severely impacted by the pandemic. (A full outline for what this initiative should look like can be found here.) Despite its potentially huge impact on students, though, summer school only deserves a smooch—not a trip to the altar—from state leaders. That’s because funding such a large-scale, statewide effort on an annual basis isn’t sustainable without federal funds, and the infusion of federal cash that Ohio has at its disposal won’t be around once the pandemic finally ends.

That doesn’t mean the state can’t continue to support remediation efforts. The second prong of Ohio’s extended learning efforts could be modeled after Tennessee’s bridge camps. These are held prior to the start of a new school year and are designed to provide additional academic support to students who need it. Ohio could temporarily—remember, this is only a kiss—offer funding for such camps to interested districts and schools during the summers of 2022 and 2023, perhaps via a competitive grant program.

Marry: Internet and device access

Ohio leaders deserve credit for putting a broadband expansion plan in place long before Covid-19 arrived, and the state ramped up its efforts to an unprecedented scale during the pandemic. As more Ohioans get vaccinated and life (hopefully) starts to get back to normal, it might be tempting for leaders to take their foot off the gas, thinking that the urgent need is diminishing. That would be a serious mistake. If there’s anything state lawmakers need to “marry,” it’s sustained efforts to provide all students with internet access and internet-enabled devices. In our increasingly digital world, they otherwise risk falling behind their peers—and the poorest among them will fall the farthest behind. That means the low-cost broadband options offered in the early days of the pandemic should be made permanent for qualifying families. Governor DeWine has already taken a good first step by allocating $250 million in his new budget plan to continue expanding broadband in underserved areas. As for devices, it’s time for Ohio’s business and philanthropy sectors to step up to the plate and help the state and local schools ensure that every student who needs a device can get one. Permanently.

Kill: Closed district boundaries

The pandemic has given families a behind-the-scenes look at what schools are (or aren’t) doing. Plenty of individual schools and districts have gone above and beyond, despite the extraordinary difficulties posed by the pandemic. But some haven’t, and others have shown that even when they make every effort to serve students well, they’re just not the right fit.

Now more than ever, parents want options that will meet their children’s needs. Which brings us to Ohio’s open enrollment policy, intended to enable students to attend school in a district other than the one in which they reside. Their families can use open enrollment to choose schools that might be closer to their homes, or to pursue academic, extracurricular, and athletic opportunities that their home districts don’t offer. The bad news is that this well-intended state policy is not actually statewide. Instead, it’s optional for districts, as they get to decide whether they want to accept non-resident students. It’s long past time for lawmakers to end (kill, if you will) closed district boundaries, which are most often found in high-performing suburbs that surround the state’s largest cities. And it’s an easy fix, too. Just amend the law so that all districts with the capacity to serve more students are required to accept non-residents.

***

State policymaking is vastly more complicated than a party game. But as lawmakers prepare to consider dozens of education policy proposals, it’s important that they sort out which ones will—and won’t—improve education. Here’s hoping that when all is said and done, Ohio will have kissed and married the policies that help kids, and killed the ones that don’t.

In a time when the “traditional” K–12 educational experience is going through upheaval and reconfiguration into myriad pandemic-influenced shapes and sizes, it is important to note that many of the so-called innovations students are experiencing are not new. Sudden shutdowns of school buildings? Been there. Asynchronous lessons? Old hat. Fully-remote learning? So last century. Even the hybrid learning models that are burgeoning at the moment are entirely precedented.

A recent research report looks at the academic outcomes achieved by one such model: the four-day school week. Created for non-emergency reasons and opted into (and out of) willingly by school districts for decades, the effects of this long-standing, untraditional model on student achievement could give us some idea of how the Covid-19 version might fare in serving students.

While Oregon has allowed districts to choose to offer a four-day school week since the mid-1990s, Oregon State University researcher Paul N. Thompson focuses in this study on the period between 2005 and 2019, during which time the number of schools using such a learning model grew, peaked, and declined. That peak number comprised 156 schools across the state. Schools opting in obtained a waiver from the state’s department of education for the amount of required school days and were required to provide a minimum number of hours of education instead. The structure of the four-day week—specifically, what, if any, work is required of students on the off-day and how it is counted toward the hours requirement—is generally up to the schools to determine. It is not described in this report, but a previous analysis by Thompson and colleagues noted that nearly half of districts surveyed closed their buildings entirely for academics on the off-day. In Oregon particularly, the off-day was widely used for athletics and other extracurriculars, many of which counted toward the state’s physical education requirements.

The baseline academic data under study—student achievement on math and reading standardized tests for grades three through eight on the Oregon Assessment of Knowledge and Skills test—showed a marked difference. Analyzing a total of 3,172,170 individual test scores from 690,804 students, and applying a variety of demographic and other controls, Thompson found that math test scores were between 0.037 and 0.059 standard deviations lower, and reading scores were between 0.033 and 0.042 standard deviations lower, for students in four-day schools versus those in five-day schools. Schools with four-day school weeks also had a smaller percentage of students meeting proficiency thresholds in math (60.7 percent compared to 64.7 percent) and reading (68.1 percent compared to 70.9 percent). This amounts to around seven to ten fewer students scoring proficient in four-day schools than in five-day schools, depending on student-body size. English language learners fared worst of all subgroups in terms of achievement declines, but interestingly, students with special needs actually bucked the trend and scored very slightly higher as a group in four-day schools than in five-day schools. These data are clear and compelling, but could there be other factors at work than simply the change in schedule?

Because a number of schools moved from four-day to five-day schedules and vice versa during the study period, Thompson was able to use a difference-in-differences research design to determine that the reduction in face-to-face instructional time explained a majority of the test score declines observed in four-day models. And for schools that moved from a four-day to a five-day week, a one-hour increase in weekly time in school led to a 0.018 standard deviation increase in math achievement and a 0.006 standard deviation increase in reading achievement for their students. These are small increases in themselves, but have the potential to compound to greater significance over multiple additional hours.

Noting that many Oregon districts reported adopting a shorter week due to financial concerns, Thompson also looked at the potential trade-off between cost savings and achievement. Oregon districts were required to submit per-pupil spending details related to the shortened schedule to the state, and he compared this to similar data from studies in other states. A $1,000 per pupil cost savings realized by a shortened week yielded an achievement loss of between 0.094 and 0.189 standard deviations. Compared to other traditional cost saving approaches elsewhere (larger class sizes, reductions in force, etc.), the academic achievement losses experienced in Oregon were the same or lower than most, but still a net academic loss.

Many schools across the country have adopted four-day school weeks out of pandemic necessity. At the same time, we are seeing evidence of very alarming academic achievement losses. Data from pre-crisis times indicate that the two things are inextricably and negatively linked. The dire achievement plunges we are seeing today are magnitudes greater than this report shows, indicating sustained and exponential harm to student learning. We likely will not see achievement rise again until we can ensure more time in face-to-face education for our students. But even that will just be the start of the uphill battle.

SOURCE: Paul N. Thompson, “Is four less than five? Effects of four-day school weeks on student achievement in Oregon,” Journal of Public Economics (December 2020).

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

When Governor Mike DeWine ordered the closure of Ohio schools last March to contain the spread of a deadly new virus, it was clear that Covid-19 would reshape the educational trajectory of many children in the state. Nearly a year into the pandemic, we now have clear evidence of its impact on student achievement.

In a new report, we analyze results from the fall administration of Ohio’s Third-Grade English Language Arts (ELA) assessment to document how the pandemic has affected student learning. Unlike other state exams, which usually take place in the spring, this test is given several times per year and thus provides an early glimpse of how Ohio students are faring. Despite the disruptions caused by Covid-19, more than 80 percent of current Ohio third graders showed up to take the test in late October and early November of 2020.

Specifically, we compared the performance of this year’s third-grade students on the fall ELA assessment to the performance of third graders in the fall of 2019. Importantly, we used detailed demographic records to account for lower participation rates among certain student subgroups in fall 2020, and to make the data more directly comparable over time. Unlike online, district-specific diagnostic tests, which raise concerns that parents may assist their children on the exams, the Ohio fall ELA assessment is administered on site and under the supervision of proctors.

Not surprisingly, the results show that student learning has suffered as a result of the pandemic. Third-grade ELA scores were considerably lower this past fall than they were the year prior. The achievement decline equates to about one third of a year’s worth of lost learning for the average Ohio third grader. The decline was more pronounced among economically disadvantaged children, and it was especially large for Black students. Indeed, Black students’ scores declined by nearly 50 percent more than those of their White classmates, representing approximately half a year’s worth of learning. These learning losses are especially alarming given the pre-existing achievement gaps between less advantaged children and their peers prior to the pandemic.

Governor DeWine let individual districts decide how to reopen this past fall, and we find evidence that the decisions local officials made mattered. Although schools that reopened for five days of in-person learning this year also saw substantial declines in third-grade ELA scores, the drop was bigger among districts where learning remained completely virtual at the start of the year. (Schools that used some form of “hybrid” learning saw declines that put them somewhere between in-person and virtual districts.)

It is important to recognize that school closure is not the only reason student achievement took a hit during the pandemic. In addition to the challenge of adjusting to new and unfamiliar modes of instruction, some children also had loved ones fall seriously ill or even die due to complications from the virus. Many families have also faced financial hardships as unemployment reached record levels. Indeed, we find evidence that rising unemployment contributed to the drop in student performance, with larger test score declines in the parts of the state that experienced the sharpest job losses. Overall, our preliminary calculations suggest that Covid-related unemployment explains approximately one-third of the decrease in average test scores statewide.

In some ways, Ohio is unusually well positioned to begin helping kids make up lost ground. Few other states administer tests in the fall, so we have earlier indicators than most about the magnitude of these learning disruptions and a clear sense about which students (and districts) have seen achievement fall the most. It is important that policymakers begin making plans to remediate these impacts sooner rather than later, a conversation that seems especially timely as districts prepare to receive substantial new federal funding under the relief bill passed by Congress in December.

The Ohio General Assembly has pending legislation that would suspend other state tests this spring. However, our analysis highlights the value of state assessments for tracking the trajectory of student learning—to ensure that our remediation efforts are working. One Ohio state legislator, rightly noting that we already knew that students fell behind academically, asked “Why do we need to put them in a testing situation to find that out?” The answer is that these tests reveal precisely which students have been impacted most severely, so that resources and other efforts can be targeted most effectively.

For example, we suspect that, prior to reading this article or our full report, few policymakers knew how much more the achievement of Black students declined or that test scores declined substantially more in areas of the state that experienced larger increases in unemployment. The data available thus far cover just one subject and grade, so the full cycle of state exams this spring will provide a much more complete picture of how the pandemic has affected student learning in Ohio and help our state develop a targeted academic recover strategy. We also hope to conduct further analyses that help us identify districts that were particularly effective at overcoming their circumstances, so that Ohio educators can identify best practices.

Of course, it makes little sense to punish school districts for the test score declines or to hold them accountable for a global pandemic that was clearly beyond their control. Ohio lawmakers were right to pause the state’s school accountability system last spring, and we agree with their decision in December to continue this pause through the current academic year. However, even in the absence of accountability requirements or the publication of detailed report cards, state exams contain invaluable information—akin to a set of “vital signs” that can help monitor the health of student learning in Ohio.

Having made the case for state exams, it is also important that we remember to look beyond test scores. In many ways, young people have borne the brunt of the pandemic. Emergency room visits related to children’s mental health are up considerably compared to previous years, and it is likely that extended school closures have allowed abuse to go undetected and unreported. With more limited access to school meals, many children have also gone hungry, even as a lack of physical activity during school closures may have also caused significant weight gain. Test scores don’t directly capture any of these impacts, and it is essential that our recovery strategy is mindful of the numerous hardships Ohio children have faced over the past year.

Now is also the time for policymakers to begin planning for the next academic year. It seems clear that vaccines will not be available for most children by then. Under current safety guidelines—which require six feet of distancing and limit school bus capacity to one child per seat—many districts may be forced to remain in hybrid mode into the next school year, almost surely causing learning losses and achievement gaps to grow further. It is important to reexamine whether these precautions will still make sense once adults have been vaccinated and, if so, be proactive in finding ways to protect students from further disruption to their learning.

We commend the Ohio Department of Education for moving quickly to share these data with the public and for working with us to make this study possible. We know of no other state education agency that put this information in the hands of educators, administrators, and policymakers so quickly. Ohio is well poised to be ahead of the pack to make the best of a tough situation, if we can use these data and what we learn from this spring’s state assessments to take action on behalf of students.

Vladimir Kogan is Associate Professor in The Ohio State University’s Department of Political Science and (by courtesy) the John Glenn College of Public Affairs. Stéphane Lavertu is Professor in The Ohio State University’s John Glenn College of Public Affairs. The opinions and recommendations presented in this editorial are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of the John Glenn College of Public Affairs, the Department of Political Science, or The Ohio State University.