Ohio’s untapped potential for postsecondary attainment

It’s early January, which means ‘tis the season to contemplate the previous year and make resolutions for the next.

It’s early January, which means ‘tis the season to contemplate the previous year and make resolutions for the next.

It’s early January, which means ‘tis the season to contemplate the previous year and make resolutions for the next. In the education policy world, leaders, advocates, and lawmakers are reflecting on a busy 2019 and gearing up for another eventful year. Academic distress commissions, state report cards, and school funding are likely to dominate this year’s headlines. But sitting on the back burner—and gradually creeping toward the front—is the issue of postsecondary attainment.

Four years ago, state leaders banded together to announce Ohio Attainment Goal 2025, a statewide objective for 65 percent of Ohioans between the ages of twenty-five and sixty-four to have a degree, certificate, or other postsecondary workforce credential of value in the workplace by 2025. The purpose of the goal is simple: Eliminate the gap between the percentage of Ohio jobs that require postsecondary education and the percentage of working-age adults who have actually earned a degree or certificate. To do this, Ohio would need an estimated 1.3 million additional adults to earn high-quality postsecondary credentials.

That’s a lofty goal, but Ohio leaders deserve credit for their efforts thus far. Governor DeWine’s administration, in particular, has worked hard to improve Ohio’s attainment numbers. Several of the governor’s proposals—including a $25 million appropriation dedicated to helping high school students earn industry-recognized credentials—made it through the budget cycle and into law. And Lieutenant Governor Husted, through events like the Aim Hire conference, has been spreading the word about the importance of connecting education and the workforce.

But there’s still a lot of work to do, and the dawn of 2020 has brought a new sense of urgency. Ohio is now halfway toward its attainment goal deadline. Over the next five years, it will be vitally important for state lawmakers, business leaders, and institutions of higher education to do everything in their power to boost attainment numbers.

A recent report from the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) provides some helpful guidance for how to do that. NSC collects data from over 3,600 postsecondary institutions, a number that covers 97 percent of all postsecondary enrollments in the United States. Last October, NSC released its second in a series of reports that takes a closer look at the country’s Some College No Degree (SCND) population.

SCND Americans are exactly what their name suggests—former students who have some postsecondary education but have not yet completed their degree and are no longer enrolled in an institution. In December 2013, the nation’s SCND population totaled 29 million. In the five years since, that number has risen to 36 million, an increase of 22 percent.

As part of their October report, NSC analyzed the 2013 SCND population to determine how many re-enrolled and completed their degree in the following five years. Overall, 3.8 million SCND students returned to postsecondary education and 25 percent of returnees went on to graduate with a degree or certificate, the majority of which were an associate degree or a sub-baccalaureate certificate. An additional 29 percent of re-enrollees were still enrolled as of December 2018. In total, more than half earned, or were working toward earning, a credential.

Ohio’s numbers (see the state data Excel sheet downloadable here) are similar to national results. In December 2013, the Buckeye State had a SCND population of almost 1.1 million. In the subsequent five years, nearly 87,000 re-enrolled at an in-state institution and an additional 36,000 re-enrolled elsewhere. Fifty-one percent of these re-enrollees have completed a degree or certificate or were still enrolled as of December 2018.

The NSC report offers an additional—and arguably even more important—analysis. Within the larger SCND population is a smaller group that NSC analysts deem “potential completers.” These former students have finished at least two years’ worth of full-time enrollment over the past ten years. They are typically younger, have attended college more recently, and were more likely to attend multiple institutions than their SCND peers. They were also more likely to re-enroll and complete a credential. Ten percent of the 2018 national SCND population are identified as potential completers. In Ohio, they make up 9 percent of the state’s current 1.3 million SCND adults.

These NSC data points offer two important takeaways for Ohio leaders who care about postsecondary attainment. First, there are over one million adults in Ohio who are already on their way toward earning a credential. NSC data shows that these adults can and do return to postsecondary institutions to complete their degrees, and focusing funding and policy initiatives on helping them would be an effective way to boost attainment numbers. Second, there is a subset of these adults—known as potential completers—who deserve special attention because they are more likely to re-enroll and earn a credential than their peers.

To effectively reach SCND adults, NSC recommends eliminating barriers related to student support services, childcare, credit transfer, class scheduling, financial aid, and other programs. These services are typically designed for traditional college students rather than returning adults, and adult learners have different needs than traditional students who come to campus straight out of high school.

The report also notes that it would be wise for institutions of higher education to consider “joining strategic partnerships within the region or nationally.” In Ohio, there are already a few of these strategic partnerships in place. College Now Greater Cleveland is working with eight Ohio colleges and universities to help students with some college credit finish their degrees. Western Governors University Ohio offers competency-based courses that can help adult learners earn degrees faster. And the Central Ohio Compact is working with plenty of partners to increase attainment numbers in the Columbus area.

But there’s still plenty left to do. If Ohio’s leaders are serious about meeting Attainment Goal 2025, we need more programs like those listed above. We also need state initiatives to be strategic about reaching Ohio’s sizeable SCND population. If we can get those two things right in 2020, the Buckeye State will be well on its way toward meeting its lofty attainment goal. Most importantly, though, there will be thousands more adults with meaningful postsecondary credentials that could greatly improve their job prospects and quality of life.

One of the most talked about education policy proposals during last year’s busy state budget season was the creation of the Quality Community Schools Support Program, which increased state aid for charter schools by $30 million. Now, nearly half a year later, that program is making headlines once again because of a potential loophole.

Let’s start with a little context. The new funding program was built around two stipulations. First, it only provides resources to charter schools that meet quality benchmarks. These standards—which my colleague Aaron Churchill called “rigorous but reasonable”—include being authorized by a sponsor with an exemplary or effective rating, scoring higher on the state report card’s performance index measure than the district in which the school is located, and receiving an overall grade of A or B for value added.

Second, the program specifically targets high-poverty charter schools. Only schools that enroll at least 50 percent economically disadvantaged (ED) students are able to access the funds. In addition, the law provides a higher amount of per-pupil funding for ED students—eligible schools receive $1,750 for each student identified as low income, compared to $1,000 for non-economically disadvantaged students.

When the program made it through the budget cycle and into law, choice advocates immediately saw its potential. Charters have long faced significant funding shortfalls compared to their district counterparts. A study published by Fordham last year found that charters in the Big Eight received approximately $4,000 less per pupil than their district counterparts. This funding gap severely limits the potential of schools, networks, and the entire sector. Newly available money would, among other things, make it possible for the state’s best networks to expand their reach and open more schools.

But that’s not all it could do. Lawmakers also recognized that, while Ohio is home to some excellent charter schools, there are charters doing remarkable work outside the state, too. Networks like IDEA Public Schools, Uncommon Schools, and YES Prep have a history of serving students well, and recruiting them and others to the state would mean more quality learning opportunities for Ohio students.

To make the state a more attractive destination for high performers, lawmakers included a method for out-of-state operators to access Quality Community Schools Support Program funds for their newly created Ohio schools. Like existing charters, new schools are required to contract with an exemplary or effective Ohio sponsor. But since they are new and therefore lack performance-index and value-added scores, they can demonstrate their quality by meeting one of the following options:

Option A: Has operated a school that received a grant funded through the federal Charter Schools Program or received funding from the Charter School Growth Fund.

Option B: Meets all of the following requirements:

These alternative methods for proving quality were intended for schools that aren’t already operating in Ohio. State Superintendent Paolo DeMaria said as much in his budget testimony: “The budget also affords new community schools the opportunity to qualify for funding if the school replicated a school that meets the above criteria or uses an operator with a record of quality in other states” (emphasis added).

The distinction that these methods were intended for use only by new schools is critical. Why? Because Accel, a large charter operator with ten Ohio schools that qualified for funding, applied for its thirty-three other schools to also receive funding—despite those schools failing to meet the required academic benchmarks. Accel based their request on a Colorado charter school they run that was awarded a federal grant a few years ago and therefore meets the requirements of Option A. (For more information, check out this detailed overview by Patrick O’Donnell of the Plain Dealer.)

It’s hard to fault operators for pursuing every possible option to get their schools more funding. But the out-of-state provisions weren’t designed to open a back door to eligibility for current Ohio schools that failed to meet rigorous quality standards. They were designed to give high-performing out-of-state operators a chance to demonstrate their quality prior to opening a new school.

Late last week, the Ohio Department of Education announced that sixty-three schools qualified for the funding. Dozens of other schools, including the thirty-three mentioned above, were denied funding because they failed to connect their Ohio operations to those in other states. This seems like a fair result. It would have been incredibly concerning if a large group of schools was able to sidestep the standards every other Ohio charter had to strive for purely because of a distant association with an out-of-state entity.

At the end of the day, every existing charter school in Ohio was given the same opportunity to earn a portion of these funds. Sixty-three of them did, and they deserve credit for that. Hopefully over the next few years, many more charters—including those that applied and fell short this time—will improve and earn funding in the next round. Until then, policymakers would be wise to revisit the language and make it crystal clear that the out-of-state option is intended only for operators who haven’t yet had the opportunity to achieve success in Ohio.

In my annual review of Ohio report cards, I concentrate on the performance of public schools located in the state’s major cities, known as the “Big Eight.” The reason is twofold. First, the need to shine a light on school quality is most acute in these areas, as student achievement falls well below state averages. Second, a large majority of the state’s public charter schools are located in the Big Eight, and we at Fordham have long sought to gauge the extent to which they provide strong educational options for children living in these high-poverty areas.

This emphasis on urban education, regrettably, means that we can only scratch the surface when analyzing other parts of the state, some of which also face academic challenges—rural communities in particular. In fact, an astute reader of this year’s report asked about how many rural schools meet our “honor roll” criteria used to identify high-performing Big Eight schools.

Examining school quality in rural communities is certainly worthwhile. Although proficiency on state exams is not as sluggish as urban areas, rural students, especially those from high-poverty areas, tend to struggle to achieve college-ready targets or complete a college degree. For instance, a recent analysis found that 20 percent of students from rural Southeast Ohio meet the ACT or SAT college remediation-free targets, 6 percentage points below the statewide average. In the low-income Appalachian counties of Monroe and Vinton, just 11 percent of students reach this college readiness goal.

Rural students are deserving of great schools that prepare them for college and career. But what does school quality look like in their neck of the woods?

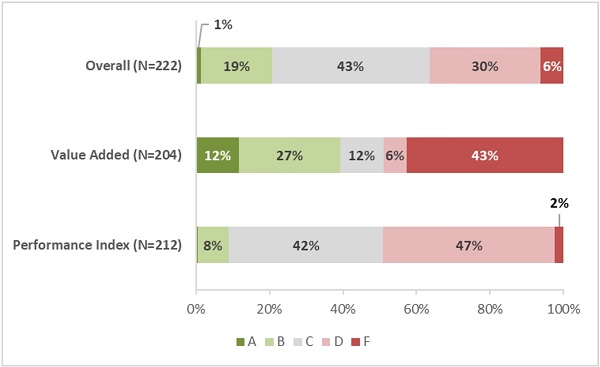

To explore this question, I split rural schools—identified as such via the state’s typology system—into two groups based on their student poverty levels. Figure 1 displays 2018–19 ratings for high-poverty rural schools, which enroll at least 50 percent economically disadvantaged (ED) students. It shows considerable variation in school ratings, especially on the overall and value-added ratings. For example, 20 percent of high-poverty rural schools earn impressive A’s or B’s on the state’s overall rating, while another 43 percent achieve respectable C’s. Meanwhile, just over one-third of these schools are struggling, having received D’s or F’s as their overall rating. The value-added results reveal even greater variation in ratings, but the performance index ratings of this group of schools are largely C’s or D’s.

Figure 1: Ratings of high-poverty rural Ohio schools, 2018–19

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: This chart displays the rating distribution of rural schools that enroll at least 50 percent economically disadvantaged students. The overall rating combines results from the various report card components (including value added, performance index, and a number of other measures); value added refers to the state’s student growth measure; and the performance index is a proficiency-based measure that reflects pupil achievement on state exams.

In comparison to the urban Big Eight, high-poverty rural schools tend to receive better ratings. For instance, 34 percent of Big Eight schools receive overall C or above ratings, while 63 percent of poor rural schools achieve that mark. The stronger overall ratings reflect these rural schools’ higher ratings on components such as the performance index, a measure on which nine in ten Big Eight schools receive D’s or F’s. The value-added ratings, however, are more similar between high-poverty rural and Big Eight schools (39 percent A’s or B’s versus 28 percent, respectively).

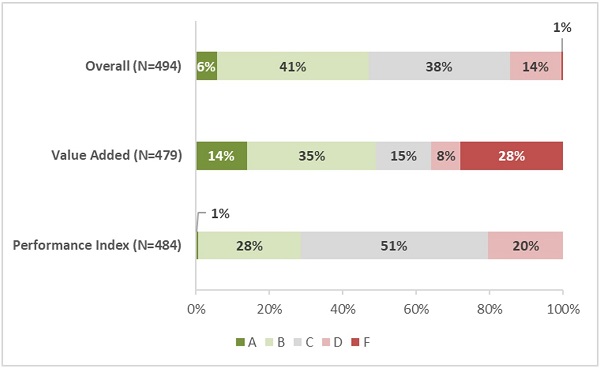

Turning to lower-poverty rural schools, Figure 2 shows that the overall ratings of this group are modestly higher than their poorer counterparts. Almost half of low-poverty rural schools achieve A’s or B’s on the overall rating and another 38 percent earn C’s. Finally, 14 percent receive overall D’s, and there are just a few F’s. The value-added ratings vary widely across the categories, and the distribution of ratings tracks relatively closely with that of high-poverty rural schools. (This is somewhat predictable as value-added ratings are less tied to school demographics.) As for the performance index, a slight majority of these schools earn C’s, while another 28 percent earn B’s. The advantage on the performance index and other “status”-type measures help to explain the higher overall ratings posted by low-poverty rural schools relative to their higher-poverty counterparts.

Figure 2: Ratings of low-poverty rural Ohio schools, 2018–19

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: This chart displays the rating distribution of rural schools that enroll less than 50 percent economically disadvantaged students. A short description of the ratings can be found under Figure 1.

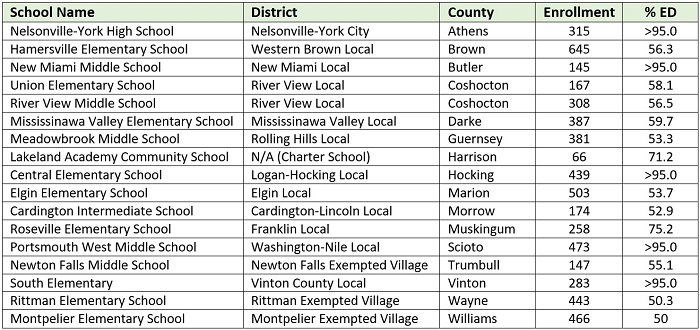

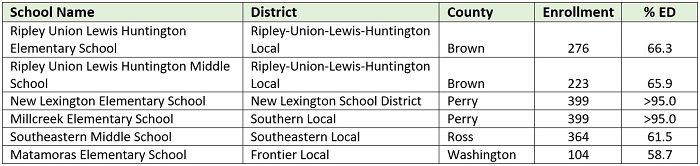

The general picture of school quality in rural areas is a mixed bag. There are a significant number of schools that perform very well overall, while other schools struggle when it comes to both growth and achievement measures. To put a special spotlight on exceptional schools that are “beating the demographic odds,” the tables below display twenty-three high-poverty rural schools that meet the same rating criteria we used to identify quality urban schools in our recent report. Table 1 shows seventeen schools that, for both of the past two years, earned an overall rating of a C or above and achieved an A value-added rating. The next table lists six additional schools that achieved these ratings in only 2018–19. The schools in the “honor roll” below represent 10 percent of all high-poverty rural schools—the same percentage of excellent Big Eight schools identified in our recent study.

Table 1: Second-year honor roll awardees

Table 2: First-year honor roll awardees

* * *

It’s well-documented that low-income students typically face more barriers to academic success. Fortunately, there are rural schools, like those in the honor roll above, that help students overcome the odds. Great schools, whether located in Ohio’s largest cities or its sparsely populated areas, are proof positive that “poverty isn’t destiny.”

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 marked a massive federal investment in our schools, with more than $100 billion to shore up school systems in the face of the Great Recession. Along with that largesse came two grant programs meant to encourage reform with all of those resources: Race to the Top and School Improvement Grants (SIGs). While Race to the Top aimed to spur system innovation, SIG was intended to facilitate turnarounds of the nation’s lowest performing public schools. Congress appropriated $3.5 billion for the first cohort of SIGs and went on to authorize five subsequent cohorts, bringing the total investment in SIG to approximately $7 billion.

There is plenty of research that examines whether this hefty price tag was worth it. Most of it is mixed, and some of the findings are downright disappointing. Back in 2017, Andy Smarick called an IES report on SIG effects a “devastating” blow to Obama’s education legacy and noted that the report “delivered a crushing verdict: The program failed and failed badly.” On the other hand, studies that have focused on state or local results—such as this one on SIG in Ohio—have been more promising.

A new working paper from Annenberg Institute at Brown University seeks to add to the discussion by offering the first comprehensive study of the longitudinal effects of SIG on school performance. The paper estimates SIG effects on student achievement and graduation rates for the first two program cohorts in four geographically diverse locations: two states, North Carolina and Washington, and two urban districts, San Francisco Unified School District and the pseudonymous “Beachfront County” Public Schools (the authors are still waiting for permission to use this district’s name). Sixty-six schools were awarded funding in the first cohort during the 2010–11 school year; and thirty-three schools awarded funding in the second cohort the following year. The data span from the 2007–08 school year through 2016–17 in order to include three years before the first cohort and three years after funding ceased. The researchers used state and district administrative datasets on student characteristics, state tests in both math and English language arts, graduation rates, and school contexts. They also controlled for changes in students’ demographic characteristics.

Results show gradually increasing positive effects during the intervention years in both math and ELA in grades three through eight. Effects were larger in the second and third year of the program than they were in the first. After SIG funding ended, positive effects began to decrease slightly, but were sustained in math through the third or fourth year post-policy (the sixth or seventh year after the school initially received the grant). Perhaps most significantly, effects on graduation were also positive: Four-year graduation rates steadily increased throughout the six or seven year period after the start of SIG interventions. Effects on students of color and low-income students were similar to overall effects and were sometimes slightly larger. Results across the four geographic locations were generally consistent but had differing magnitudes, a finding that’s in line with previous research indicating that variations could be a result of local design and implementation decisions.

The authors note that these findings suggest that SIG interventions could be one of the federal government’s most successful capacity-building investments for improving schools’ low performance. In fact, the researchers note that SIG effects on test scores in this analysis are “similar to the effects on student test scores estimated for the market-based reforms in New Orleans after the Hurricane Katrina in 2005.” But the fact remains that other reputable and wide-ranging studies found far less positive results. As Chad Aldeman notes, it appears the best question regarding SIG effectiveness is “not ‘did SIG work?’ but rather ‘why did it produce results in some places and not others?’”

SOURCE: Min Sun, Alec Kennedy, Susanna Loeb, “The Longitudinal Effects of School Improvement Grants,” Annenberg Institute at Brown University (January 2020).

Against the backdrop of Ohio’s Attainment Goal 2025, the state’s annual report on college remediation rates—the number of first year college students requiring remedial courses before beginning credit bearing work—has taken on a greater significance in the past few years. This year’s report, looking at five-year trends from the fall of 2014 through the fall of 2018, offers comforting numbers but a frustrating lack of context.

First up, the numbers. It is important to note that these data pertain only to public K–12 students in district, charter, and independent STEM schools; no private or homeschool data are included. Overall, public high school enrollment in Ohio decreased by 4.8 percent over the period. Yet the total number of graduates has increased during that time—up more than 3 percent between 2014 and 2018—because of an increase in the graduation rate. White and Asian students graduated at higher rates in 2018 than students in all other racial categories. Students who were economically disadvantaged (ED) were less likely to graduate than their non-ED peers across all racial categories, but that correlation was especially prominent among white, non-Hispanic students.

Nearly 42 percent of Ohio’s 2018 public high school graduates went on to enroll in a public college or university in the Buckeye State that fall. Black and Hispanic students were underrepresented among first-time college students as compared to the demographics of the 2018 graduating class, although students identifying as multiracial had higher representation. It is also important to note that the data in this report are only tracking matriculation at in-state public institutions. Students attending private colleges in Ohio or any institutions outside the Buckeye State were not tracked.

Overall remediation rates for first-time Ohio college students in 2018 went down in both math and English, continuing a nearly-unbroken five-year decline. While no breakdown was provided by race or ethnicity, remediation rates for ED college students, while also trending downward, were seen to be nearly double those of non-ED students.

Unfortunately, the report gives very little in the way of context. It connects the decline in remediation with a plethora of important K–12 efforts—strong learning standards, early interventions, quality preschool, the state’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee—but cannot, obviously, get to any sort of direct relationships between these interventions and observed outcomes. That is especially true since certain reforms—preschool and early literacy—haven’t been in place long enough to impact the 2018 senior class. Thus the main recommendation of the report is for Ohio to keep on keepin’ on. A recent interview with a spokesperson for the Ohio Department of Higher Education about the report was even clearer in being opaque: “There really are too many variables involved to speculate on what exactly has contributed to the continued decline in the remediation rate.”

However, in that same news item, a University of Cincinnati professor suggests more caution in interpreting the report’s findings: “It remains to be seen whether there has been real improvement in college readiness or simply some gimmicky addressing of the problem.” His implication is that students who are not ready for credit-bearing college coursework are simply not being given remediation because of the state’s drive to reduce remediation. There is some evidence for this supposition given the relatively flat ACT scores and state test results. If Ohio is experimenting with allowing students who haven’t met remediation free standards to bypass remedial courses or to take classes that count for both remediation and college credit, the state needs to be clearer, as otherwise it appears we’re engaging in bar lowering and sidestepping educational accountability rather than actually improving outcomes.

While ODHE’s report is a legislative mandate and is, ultimately, only intended to provide the data it does, Ohio’s high school graduates deserve more. The state is aiming high with its Attainment Goal 2025. A true all-hands-on-deck approach to boosting college persistence and completion would go beyond the mandate—beyond vague numbers presented without context—and connect the dots.

SOURCE: “2019 Ohio Remediation Report,” Ohio Department of Higher Education (December, 2019).

With little fanfare, Columbus Preparatory Academy regularly appears near the top of the charts when it comes to state test scores. In 2018-19, for example, its performance index score ranked twelfth out of 3,225 Ohio public schools.

In our latest Pathway to Success profile, author Lyman Millard of the Bloomwell Group offers some hints about the secret sauce of this Columbus-based public charter school. It all starts with a culture of high expectations, but it also includes some unique twists including a two-month initiative known as “The Blitz” (you’ll have to read the report to find out more).

To some, such a laser-like focus on academics might sound a little too intense. But it’s clear from this profile that the school’s educators have bought in—and just as importantly, students seem to embrace the challenge, too. As one student remarks, “They saw potential in me that I didn’t see in myself and really pushed me to do my absolute best.”

For the 800-plus students attending Columbus Preparatory Academy, their school is raising the bar on academic rigor.