The special subsidies baked into Ohio’s new funding formula

Politicians are notorious for handing out subsidies for certain projects and sectors

Politicians are notorious for handing out subsidies for certain projects and sectors

Politicians are notorious for handing out subsidies for certain projects and sectors of the economy. These goodies help them stay in power and appease special interests. But as Chris Edwards of the Cato Institute argues, they also create an uneven playing field in which legislators pick winners and losers at taxpayer expense. Unfortunately, Ohio’s new funding system isn’t immune to this pork-barrel practice. This piece looks at two special subsidies—one favoring small districts and the other larger, urban ones—that are baked into the new funding model. Legislators should reevaluate the need for both as they review the new formula in the coming months.

Small district subsidy via staffing guarantees

In last year’s overhaul of the formula, Ohio lawmakers created a new set of calculations that attempt to “cost out” what it takes to educate a typical student. To do this, the model relies on staff-to-pupil ratios, average employee salaries and benefits, and spending on other educational “inputs.” The computations produce a base cost for each district, which is then used in conjunction with a measure of property and income wealth to determine the bulk of state aid that districts receive. The basic equation is as follows:

That’s a lot to digest. But the key things to know for the purposes of this analysis are: (1) the base-cost per pupil is a critical factor in determining a district’s state funding and (2) the new formula yields variable bases that differ across Ohio’s 600-plus school districts. The latter is a significant turn from the previous formula which set a fixed base that applied to all districts, most recently $6,020 per pupil.

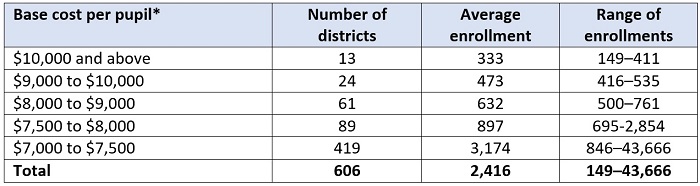

Table 1 shows a breakdown of base cost per pupil across Ohio districts. Most districts—roughly two in three—have bases within a narrow range of $7,000 to $7,500 per pupil. But a number of districts have higher amounts. Thirteen have bases above a whopping $10,000 per pupil—and all of them are teeny-tiny districts with enrollments ranging between 149 and 411 students. The next highest tier of base costs—$9,000 to $10,000—also consists of small districts with only slightly higher enrollments (average of 473). Only when we pass about 1,000 students in a district do the base costs settle into the more “normal” range.

Table 1: Ohio school districts’ base costs, FY 2022

* The statewide average base cost is $7,349 per pupil. While not included in this table, charter schools’ base-cost model is somewhat different and yields an average base of $7,337, with a range of $6,824 to $8,586 per pupil. Due to the phase-in of the HB 110 funding model, districts and charters are not actually being funded at these base amounts in FYs 2022–23 (these would be the amounts under a fully-funded formula). Source: Ohio Department of Education, Foundation Funding Report (FY 22 May #2 payment file).

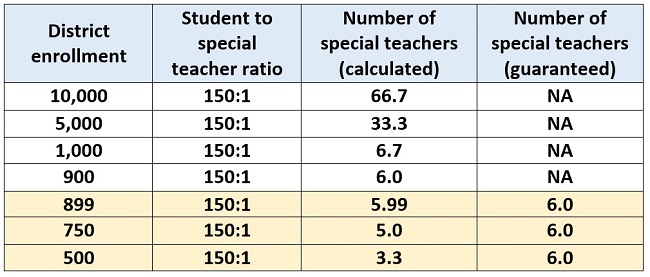

What is causing this escalation in base costs? It’s actually due to a mechanical quirk in the base-cost model. As mentioned above, this model relies on student-to-staff ratios to determine the number of employees assumed to be needed—and thus “costed out”—in a district. Things get interesting, however, due to a policy that guarantees a minimum number of employees in certain staff positions. Table 2 shows how the minimum plays out for the “special teachers” (e.g., arts, music, and PE) portion of the base-cost model. Districts with more than 900 students are prescribed special teachers strictly by ratio (150:1). But those with enrollments under this threshold receive more teachers (six) than what the formula otherwise prescribes.

The upshot: The staffing minimums increase the per-pupil base costs for Ohio’s smallest districts—they are, for formula purposes, “overstaffed”—which in turn, inflate their state funding.[1] By my ballpark estimation, the minimums would cost the state roughly $150 million to $200 million per year under a fully implemented formula, or about 2 percent of the state’s annual funding for K–12 education.

Table 2: How the special-teacher staffing minimum works

The staffing minimums give Ohio’s smallest districts—though interestingly, not charter schools, which serve comparable numbers of students—special treatment through the base-cost model. Some may argue that small districts face higher costs due to lack of scale. But there are ways that districts can operate cost-effectively. One possibility, strongly encouraged back in 2012 by the Kasich Administration, is to share services and personnel. Small districts, for example, could team up to share art and music teachers or administrative and maintenance staff. Some districts, in fact, already do this: Cloverleaf and Medina, for instance, share a treasurer. Districts could also leverage regional educational service centers, joint-vocational districts, or institutions of higher education to provide special programming, college and workforce counseling, or back-office support.

In the end, no district has to go it alone. Opportunities abound to build scale without sacrificing—and perhaps even enhancing—educational quality. Districts also don’t have to do this through consolidation; this can all be done organically and voluntarily without losing local autonomy. Unfortunately, the formula’s small-district subsidy—buried deep within the base-cost model—discourages cost-effective problem solving that can benefit both taxpayers and students. Moving forward, legislators should remove this special subsidy by eliminating the staffing minimums from the base-cost formula. All districts’ base costs—and charters’ too—should be calculated in the same manner. In a formula touted as the “fair school funding plan,” that’s only fair.

Urban district subsidy via “supplemental targeted assistance”

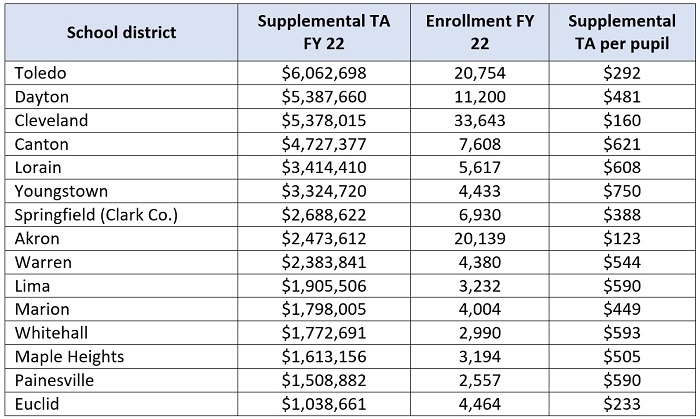

Ohio’s smallest districts aren’t the only beneficiaries of an extra subsidy that deviates from formula calculations. Also hidden in the funding system is a new $54 million per year outlay called supplemental targeted assistance. If a district had a sizeable proportion of students in choice programs and was relatively poor in FY 2019, it receives these funds. Based on these parameters, just thirty-six districts got the extra funding. Table 3 displays the districts that received more than $1 million in supplemental targeted assistance in FY 2022. Taken together, these fifteen districts—largely big-city and inner-ring urbans—collected 84 percent of the total subsidy ($45.5 million). Note that much like the staffing guarantees, charters are not eligible for these dollars.

Table 3: Districts receiving the most supplemental targeted assistance (TA) in FY 2022

Source: Ohio Department of Education, Foundation Funding Report (FY 22 May #2 payment file).

Though not an enormous amount, the dollars funneled through this component are another unnecessary subsidy, this time propping up urban districts that have historically “lost” significant numbers of students to choice programs. It’s clearly not formula-driven funding; it’s not at all tied to a district’s current enrollments and wealth. Instead, it looks back on old data to provide excess dollars to an extremely narrow group of districts (just 6 percent of them). Maybe legislators intended it to be a “payoff” to districts that have long bemoaned the transfer of state funds to students’ schools of choice. If that’s the aim, it sure isn’t working. Toledo Public Schools—the largest beneficiary of the subsidy in absolute dollars—recently joined the lawsuit against EdChoice (perhaps using these funds!).

Now, sending extra funds to select districts—ones getting strong results for kids—would make perfect sense in a performance-based funding component. But that’s hardly the case here. In fact, one could view it as a bizarre reward for districts that have fared poorly in meeting the needs of resident families. And while many of these districts are high-poverty, that is addressed through the other mechanisms in the formula, including—as noted above—the “state share percentage,” which ensures that more state aid is steered to poorer districts, along with a large funding bucket based on economically disadvantaged student counts. In sum, this funding stream sends extra dollars—more than what the formula prescribes—to a small number of districts for reasons that simply don’t make good sense.

***

The proponents of the HB 110 model regularly argued last year that a school funding formula should treat all districts fairly—without favoring certain ones over others. And they’re right. But the current formula doesn’t quite achieve the promised goal due to the special carveouts discussed here. As legislators consider whether to fully fund this system as is or make changes to it, they should work to ensure that all schools receive dollars under an evenhanded formula.

[1] In addition to the special-teachers minimum, districts are guaranteed at least five student-wellness-and-success staff, two district administrators, two fiscal-support staff, one high school counselor, one superintendent, one treasurer, one EMIS staff, one administrative assistant, and one school-level clerical staff.

There’s a growing body of research confirming the positive impact of extracurricular and enrichment activities for kids. Field trips help students improve critical thinking and boost factual knowledge. Consistent participation in extracurricular activities between eighth and twelfth grade predicts academic achievement and prosocial behaviors. The academic eligibility requirements high school athletes must meet have decreased dropout rates among at-risk students, and increased participation in high school sports has been especially good for girls.

Unfortunately, participation in extracurricular and enrichment activities is less common among students from lower-income families, largely due to the cost of participating and a dearth of opportunities. A 2014 analysis of four national longitudinal surveys of American high schoolers found growing income-based differences in extracurricular participation, which could be attributed to rising income inequality. The pandemic has made things worse: Providers have closed, low-income families have less to spend, and the enrichment gap is widening.

To its credit, Ohio has taken a direct approach in attempting to diminish this gap. During the last budget cycle, state lawmakers used federal Covid relief funds to create the Afterschool Child Enrichment (ACE) educational savings account. ACE provides families whose income is at or below 300 percent of the federal poverty line with $500 per student that can be used to pay for a variety of enrichment activities for children between the ages of six and eighteen. Activities include (but are not limited to) before- or after-school educational programs, day camps, field trips, language or music classes, and tutoring. ACE accounts can be opened for any student who attends a public or private school, as well as for those who are homeschooled.

ACE has the potential to help a lot of families. Considering the benefits outlined above—not to mention the equity implications of ensuring that all Ohio children have access to extracurricular and enrichment opportunities—getting ACE up and running in an effective and efficient way is extremely important. Unfortunately, three implementation challenges have so far limited the initiative’s impact.

1. The program’s launch was delayed

According to the Ohio Revised Code, the program was supposed to be up and running by the end of January so that families could create their accounts and have plenty of time before summer—prime time for enrichment and extracurricular activities—to choose a provider and services for their child. But that deadline wasn’t met. According to the user manual for applicants, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) didn’t start accepting requests from families to determine their ACE eligibility until April 11. That’s more than two months after the deadline set by lawmakers. This delay left families who wanted these funds to access summer programs just a few weeks to fill out all the necessary paperwork, get approved, and identify a provider. The recently passed House Bill 583 took some of the timing pressures off families by allowing unspent ACE funds to remain in accounts until students graduate from high school. But that adjustment doesn’t change the fact that families who wanted to use ACE funds this summer were severely limited in their ability to do so.

2. The application process is burdensome

Once the program was finally up and running, families had to deal with a lengthy and confusing application process. Although the instructions for parents and guardians posted on ODE’s website seem simple enough, the user manual for applicants outlines several steps. First, families must create an OH|ID account, a system that allows Ohioans to securely access several state agencies. Next, they must create an Ohio Department of Education profile within the OH|ID system. After that, they need to round up their income verification documents—the previous year’s W2 or federal tax return, four current pay stubs, and official documentation showing unemployment are among the acceptable documents—and then electronically submit them. Once all these steps have been completed, families can apply for an ACE account. ODE notes that it can take up to two weeks for income verification to be complete, and that even once families are approved for an ACE account, they must also sign up with Merit International, the vendor chosen by ODE to manage ACE. It’s also worth noting that this entire process is online—bad news for families that don’t have reliable internet access or internet-enabled devices—and that all ODE offers as ongoing support for families is an email address where they can send their questions.

3. Many families seem unaware that the program exists

One of the defining features of the enrichment gap is that low-income students don’t have the same access to extracurricular opportunities as their more affluent peers. That’s why it’s so unfortunate that even though lawmakers created a program to address the access gap, the state hasn’t done a good job of notifying families of the opportunity. Recent coverage in Gongwer notes that although $50 million was allocated to support the program during its first year, only $106,749 in claims have been approved so far for just over 6,000 families. Sue Cosmo, the director of ODE’s Office of Nonpublic Educational Options, acknowledged that the program is “well below capacity” both in terms of participating families and providers, and that the department is “working on developing a package of marketing materials and social media content” to increase awareness and participation. Hopefully those efforts come to fruition sooner rather than later.

***

It’s worth noting that the issues outlined above aren’t the only problems currently plaguing the ACE program. Anecdotal reports also indicate that the reimbursement process is slow and cumbersome for both families and providers, and that there are several geographic regions that lack services, making it difficult for some approved families to actually use their ACE dollars. It’s understandable that some challenges would surface in a first-year program. But given the potential of ACE accounts and how important these opportunities are for kids, fixing these issues is critical. As the program enters its second school year, the state needs to streamline the application and reimbursement processes as much as possible, offer better support to families who have questions and need help, and do a much better job of spreading the word that the program exists. Getting these details ironed out will ensure that more Ohio families can take advantage of this worthwhile program.

The education world was abuzz last Tuesday as the U.S. Supreme Court released its opinion in Carson v. Makin. The Court struck down a provision in Maine’s tuition assistance program that barred families from using public funds to attend religious private schools, a ruling that could have far-reaching effects for school choice in America. While Carson has attracted much attention in the media, its link to Ohio has received scant mention. This is an unfortunate oversight, as a separate Supreme Court case that began in the Buckeye State twenty years ago helped set the precedent for the decision.

The story begins in Cleveland. As part of a host of reforms intended to address the Cleveland Metropolitan School District’s chronic low performance, Ohio introduced a new voucher program, the Pilot Project Scholarship Program, in the fall of 1996. Eligible students received grants of $2,250 per year to attend private schools in the Cleveland area. Religious schools were permitted to participate in the program, but no participating school could discriminate against students on the basis of race, religion, ethnicity, or national origin.

The inclusion of religious schools rankled some citizens. Doris Simmons-Harris filed a lawsuit against then-state superintendent of public instruction Susan Zelman, claiming that Ohio had violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. After much legal wrangling, the case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

Zelman won in the end. Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote the 5-4 majority opinion that declared Ohio had not violated the Constitution. He stated that the Cleveland voucher program was “neutral in all respects toward religion.” State funds were not going directly to religious schools; they were going to families, who made the decision to attend a secular private school or a religious one. It was the first time the Court ruled that states were permitted to steer public dollars into religious elementary and secondary schools.

With a victory in the Supreme Court secured, Ohio expanded the voucher program over the coming decades. Today, more than 7,000 Cleveland students today attend a private school using a state-funded voucher, and roughly 57,000 Ohio students participate in the EdChoice voucher program—a statewide program operating since 2006. According to one estimate, 97 percent of voucher funds went towards religious schools in the 2015–16 school year.

While Zelman settled the issue of whether a voucher program violated the Establishment Clause by including religious schools, Carson v. Makin considered whether Maine’s tuition program violated the Free Exercise Clause by excluding religious schools. Much of Maine is rural and sparsely populated—so much so that there are not enough students in some communities to maintain a high school. Where there is no option for a public secondary school, the state provides tuition assistance for students to enroll in private schools. A change to the law in 1981 required that these schools be “nonsectarian.” This motivated a lawsuit by two families who, lacking a public option, enrolled their children in religious private schools and therefore could not participate in the tuition program.

A 6-3 majority of the Court sided with the families, finding that the state “violates the Free Exercise Clause when it excludes religious observers from otherwise available public benefits.” States are under no obligation to support private schools, the Court ruled, but if they do, they can’t leave out religious ones. Citing Zelman in the majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts stated that “a benefit program under which private citizens ‘direct government aid to religious schools wholly as a result of their own genuine and independent private choice’ does not offend the Establishment Clause.” Indeed, in the course of just two decades, the Court went from permitting the inclusion of religious schools in tuition assistance programs to requiring it.

Zelman was even cited in two of the dissenting opinions, albeit to different ends. Justice Stephen Breyer—one of two justices remaining from the Zelman court—referenced his previous dissent and his belief that there is “play in the joints” of the two religion clauses. In his view, this allowed Maine to include religious schools in its tuition program but did not require Maine to do so. In her own dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor took a dim view of Zelman, citing it as example of when the Court "eroded” the separation between church and state.

It is not clear what the long-term effects of this decision will be. While some have suggested that it opens the door to religious charter schools, others are more reserved. What is clear is that the Cleveland voucher program—and the Supreme Court’s landmark Zelman decision—played a crucial role in determining the shape of school choice for the rest of the nation.

Research shows that many talented students shy away from a career in education due to salary concerns. As a result, increasing teacher salaries is often pitched as a potential solution for teacher shortages. But a recent paper from the Annenberg Institute at Brown University challenges the assumption that salary increases are the best method for investing in the teacher workforce by examining an alternative set of benefits and estimating how attractive teachers found them in comparison to salary bumps.

To determine teacher preferences, the researchers used an online survey that was emailed to teachers between November 2020 and January 2021. The final sample included a total of 1,030 teachers. Similar to the national teacher workforce, the sample was 75 percent female, 81 percent white, and contained a roughly equal share of primary and secondary teachers. Unlike the national workforce, however, the sample skewed slightly less experienced, and under-represented teachers from rural areas.

The survey presented teachers with pairs of hypothetical teaching jobs and asked them to identify which school they preferred. The researchers defined each school according to seven features: salary, childcare benefits, class size, and four key support roles—school counselors, nurses, special education specialists (paraprofessionals and co-teachers), and instructional coaches. The values were randomly assigned, and teachers were asked to hold constant all unstated features of the schools via the following prompt: If two schools were otherwise identical in every way—same building, same principal, same teaching assignment, same students—which school would you prefer?

Results reveal that teachers valued working in a school that provided a full-time nurse, full-time counselor, full-time special education paraprofessional, and a full-time special education co-teacher as much or more than a 10 percent increase in salary. On the other hand, teachers valued a three-student reduction in class size and one hour of instructional coaching per month less than they valued a 10 percent salary increase. Unsurprisingly, preferences for childcare benefits depended on the size of the benefit and whether the teacher currently had children.

The researchers classified a benefit as cost effective if the amount teachers were willing to sacrifice in additional salary to receive the benefit exceeded the per-teacher cost of offering it. Assuming an average teacher salary of $60,000 and an average of thirty-three teachers per school (both of which were, indeed, the national averages at the time of the survey), the researchers estimate that investments in nurses and counselors are highly cost effective. The average teacher is willing to forego a 13 percent salary increase ($7,800) to work in a school with a nurse, which is more than five times the per-teacher cost of employing one. Findings regarding school counselors were similar. The researchers estimate that working in a school with one full-time counselor is worth $7,487 in salary equivalents to teachers, while working at a school that employs two full-time counselors is worth $9,952. These equivalents are, respectively, worth more than four times and almost three times the per-teacher cost of employing one or two full-time counselors.

Teachers were most willing to sacrifice a pay raise for special education staffing, which isn’t surprising in light of recent research showing that the percentage of students with disabilities in teachers’ classes was associated with an increase in the odds of turnover. Survey results indicate that the average teacher would be willing to forego a 12.5 percent salary increase for full-time support from a paraprofessional, and a 16.6 percent increase for full-time support from a co-teacher. Unfortunately, the costs of offering this one-on-one support are much higher than estimates indicating what teachers are willing to pay. Based on the benefit to teachers alone, it’s difficult to justify the expense of adding special education support to every classroom. But like nurses and counselors, these support staff also benefit students and families, who aren’t included in this study and may make the cost more palatable for school leaders.

Teachers were least willing to pay for smaller class sizes. The offer of instructional coaching did not appear to strongly influence teacher preferences, either, though estimates indicate that coaches are worth roughly $2,500 in salary equivalents, which is more than double the approximate per teacher cost. As for childcare benefits, eligible teachers valued a 10 percent salary increase and a $3,000 per-child subsidy (with a $6,000 annual cap) similarly, but preferred the 10 percent increase over a benefit of only $1,500 per child. Interestingly, the researchers observed that teachers who didn’t have children still seemed to find a hypothetical school that offered childcare benefits more attractive than a school that didn’t.

Overall, these findings indicate that many teachers prefer investments in support staff rather than increases in salary, class-size reductions, or more instructional coaching. The paper offers several plausible explanations as to why. First, support staff such as counselors, nurses, and special education specialists provide services to students that are necessary and help ensure they’re ready to learn. Teachers recognize these needs and understand the importance of meeting them, but they may feel ill-prepared or unable to do so. Second, surrounding teachers with student-based support professionals frees up time so they can focus on core instructional duties. Allowing teachers to focus on teaching can in turn lead to academic gains for students. Third, sharing the responsibility for students’ well-being among a variety of professionals can reduce teacher stress and prevent burnout, which is crucial for retention.

The big takeaway here for policymakers and district leaders is that while salary matters, it shouldn’t be the exclusive focus when it comes to recruitment and retention efforts. Teacher preferences also matter immensely, as research indicates that working conditions have a strong influence over teachers’ employment decisions. To effectively invest in the teacher workforce, leaders should focus on a broad set of benefits, and that includes offering teachers what they say they want.

Source: Virginia S. Lovison and Cecilia H. Mo, “Investing in the Teacher Workforce: Experimental Evidence on Teachers’ Preferences” Annenberg Institute at Brown University (February 2022).

In 2016, the U.S. Department of Education launched an offshoot of the Pell Grant program intended to assist low-income high schoolers in accessing college credit through dual enrollment. (Generally, only high school graduates are eligible to receive Pell Grants.) Various forms of dual enrollment were burgeoning at the time, but concerns also persisted that those same students traditionally underserved by Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate programs were being locked out of this version of early college credit acquisition, especially due to cost. Each state that offered dual enrollment ran its programs differently, including who paid and how much. The federal effort was meant specifically to overcome financial hurdles for low-income students, building off the traditional Pell Grant model. A recent evaluation published in the journal AERA examines participation in the dual-enrollment support program, as well as its impact, after three years of implementation.

Using student level data from ACT, Inc., the researchers look at four states that each had at least one post-secondary institution participating in the Pell Dual Enrollment program (PDE) and that administered the ACT college entrance exam to all high school juniors. They focus on the graduating cohorts of 2017, 2018, and 2019, who would have been eligible to participate starting in their junior year, and they identify a full sample of 1.6 million students who lived in proximity to any dual enrollment-offering institution in those four states during those years. The National Student Clearinghouse provided data on any college course participation during high school and any subsequent postsecondary enrollment of all students in the sample.

Only 2 percent of students in the sample lived within twenty miles of a PDE institution. And while some dual-enrollment programs provided courses at students’ high schools, the researchers assume—based on their interviews with staff at a number of postsecondary institutions—a requirement that students must participate on campus. Thus, while nearly 25 percent of all students in the sample signed up for at least one dual-enrollment course in their high school careers, the vast majority of these were at non-PDE institutions.

They then focused on a subset of the sample whose reported family income was less than $50,000—well below the typical Pell-eligibility threshold of $100,000—to determine whether the students intended to be helped by PDE were taking advantage of it. The treatment group in this case are those Pell-eligible students living near a PDE institution; the control group are Pell-eligible students living near a non-PDE institution.

A difference-in-differences analysis showed that proximity to a PDE institution actually reduced the likelihood of Pell-eligible students’ participation in dual enrollment at all. This effect was most pronounced for students who live in high-poverty zip codes and whose parents did not attend college. They were 9 percentage points less likely to participate in dual enrollment than were their peers living near non-PDE institutions. The PDE program also appeared to have no statistically significant effect on college enrollment after high school graduation for any group.

In looking for mechanisms to explain how an access-support program actually suppressed utilization, the researchers discuss anecdotal evidence gathered from dual-enrollment-offering colleges across the country. As noted above, the varying state rules for dual enrollment often related to families’ cost. Some states already provided full financial support through K–12 funding, some left payment up to interested families, some included books and lab fees in that support, others just tuition. The value of the PDE support was effectively different for families in different places, thus creating a useful support for some while leaving insurmountable hurdles for others. College officials interviewed also pointed the finger at high school staffers—especially guidance counselors—for either misconstruing dual enrollment as “free credits” to everyone when it wasn’t or for not telling eligible students about the PDE support at all, leading to applicants who could not afford to follow through or PDE beneficiaries being entirely unaware of the opportunity.

Additionally, colleges with established dual-enrollment programs (and experienced staffers dedicated to that work) who could potentially wade through the minefield of confusing information on behalf of students were less likely to offer PDE programs. A number of institutions visited by the researchers started offering dual enrollment because of the new federal incentive but were unfamiliar with many of the difficulties already surmounted by their peer institutions. The analysts conclude from this evidence that federal requirements—including FAFSA completion and other income verification paperwork—were onerous and were largely left to families to manage. If college officials were available to help, anecdotal evidence suggests more Pell-eligible students were able to surmount these and other bureaucratic roadblocks.

The report ends with a tiny bit of hope: As high schools and colleges gain more experience with the PDE program, more students intended to be aided by it will be able to access it in 2020 and beyond. However, PDE was actually cancelled in 2021 due to the low utilization rates that were observed by the researchers, which persisted beyond their analysis period. Be it availability or proximity or money or a paperwork burden, any one or a combination of factors could have served to deter a Pell-eligible student’s participation in dual enrollment, thus dooming the effort. Evidence strongly suggests that adding the additional layer of federal bureaucracy did nothing but increase the difficulty for students who were already being locked out of dual enrollment.

SOURCE: Eric P. Bettinger, Amanda Lu, Kaylee T. Matheny, and Gregory S. Kienzl, “Unmet Need: Evaluating Pell as a Lever for Equitable Dual Enrollment Participation and Outcomes,” AERA (May 2022).