Student wellness and success funding could make Ohio a national leader in providing wraparound services

It’s budget season in Ohio, and that means frenzied debate about a wide swath of policy proposals.

It’s budget season in Ohio, and that means frenzied debate about a wide swath of policy proposals.

It’s budget season in Ohio, and that means frenzied debate about a wide swath of policy proposals. In education, the debates have mostly centered on accountability: academic distress commissions, school report cards, and graduation requirements in particular. What hasn’t been discussed—at least not at length and certainly not with as much intensity—is one of the largest new funding streams that Governor DeWine’s team has proposed: student wellness and success funding (SWSF).

SWSF is intended to do exactly what its name implies—improve student wellness by addressing non-academic needs. The governor has proposed a $550 million pot of funds that would be available for all public schools and awarded on a per-pupil basis, based on the percentage of low-income children residing in a district. Districts with higher percentages would receive more funding. Districts and schools would be required to submit a report to the Ohio Department of Education that outlines how they used their funding. Spending is limited to the following ten areas:

Unlike some of the governor’s other proposals, the House changed very little about SWSF in its version of the budget. In fact, the only major change was to increase funding by $25 million for FY 2020 and a whopping $100 million for FY 2021. This substantial funding increase, as well as widespread praise for the policy, indicates that SWSF could become one of those rare education policy proposals that passes without inciting bitter debate. (Of course schools usually don’t object to more money!)

This lack of fanfare isn’t totally surprising. Funding for non-academic supports—also called wraparound services or integrated student supports, depending on whom you ask—is becoming increasingly popular. For many folks, it’s a moral issue. Millions of kids across the country, particularly those from low-income communities, have serious non-academic needs that aren’t being met. It feels wrong to just do nothing, and schools seem like a logical place to house supportive services. And lest one think that supportive services are outside the realm of a school’s mission, there’s an academic motivation, too: Successfully addressing outside-of-school factors that affect learning could lift academic achievement.

But research on whether that strategy actually works is mixed. Last year, Matt Barnum at Chalkbeat tackled the big question of whether wraparound services boost achievement. He wrote that the findings vary depending on the program that’s under the microscope, but overall results from nineteen rigorous studies show “a mix of positive and inconclusive findings.” Results for non-academic outcomes, such as attendance and behavior, are inconsistent. And it’s “frustratingly” unclear what makes a program actually work.

A more recent Education Next article from Michael McShane comes to similar conclusions. While some studies show that students develop improved attitudes about school and better relationships with peers and adults, there is little to no evidence of improved achievement, attendance, or behavior. Evidence on what high-quality implementation looks like is incomplete. In total, “large-scale evaluations of wraparound programs to date have shown only small benefits to student achievement, at best.”

To be clear, asking what works in education is way more complicated than it seems. Rigorous research is important and should be taken seriously, but it would be unwise to ignore the outsized importance of local context and implementation efforts. That’s why Ohio’s SWSF proposal, which puts much of the spending power in the hands of local rather than state officials, could become a national model.

It is absolutely critical for schools and districts to have full control over how they spend this funding. Students in urban districts have different needs than those who attend rural or suburban schools, and varying age groups need different types of support. Local leaders and educators know their students and their needs far better than anyone in state government does. But teachers and administrators already struggle with overfull plates. Even if they opt to use service providers and existing organizations rather than providing services in-house, identifying the right organizations and coordinating with multiple providers could be difficult at best and a disastrous waste of money at worst.

There are a few ways the state can help. First, the Senate should add a provision to the budget bill that would allow districts to hire site coordinators to oversee SWSF efforts. Hiring a coordinator shouldn’t be mandatory. Some schools may already have the right personnel in place, or they may have existing relationships with service providers that would make a coordinator unnecessary. But schools that are starting from scratch should be explicitly permitted to use their funds to hire a full-time staff person to ensure that implementation efforts are successful.

Second, lawmakers should call for the department to do more than just collect reports from schools on how funds were spent. The state should be evaluating whether these funds succeeded in improving student wellness and achievement. Determining which programs and initiatives improved student outcomes and in what context they were successful is critical, something that a previously acclaimed initiative, the Straight A Fund, failed to do. Evaluating schools’ wellness programs will enable educators to identify which make the biggest difference and hold the most potential for replication elsewhere—and those that seem to have no effects.

Third, lawmakers should direct the department to create a list of quality service providers and programs based on the information they gather from districts. This list should include a brief overview of which services an organization offers, how those services are offered, and where and when they can be offered. It should also include any available data on student outcomes. This list should not be used as an accountability mechanism for providers. And schools shouldn’t be limited to working with only those providers on the list. Instead, it should function as a resource that makes it easier for schools to track down high quality partners who will help them implement SWSF plans with fidelity.

All in all, Ohio’s got a pretty big opportunity before it. The evidence that integrated support services can impact academic outcomes is mixed. But it makes sense for schools to support student health and wellness for their own sake, and Governor DeWine and his team should be praised for proposing a bold plan with an eye toward maximum student benefit. With just a few tweaks, this ambitious plan could prove transformative for students—and make Ohio a leader for the rest of the nation.

Over the past two years, the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan has received tremendous attention in the media and at the statehouse. Currently, House lawmakers are considering what changes might be made to the plan, as laid out in House Bill 1. Despite all the hoopla and multiple iterations of the proposal, important details still need to be ironed out. The public hasn’t yet been informed about how the state will pay its $2 billion price tag, funding for public charter schools and independent STEM schools remains inequitable, and the base cost model could create headaches for future lawmakers. Two additional issues, not yet discussed on this blog, also deserve further scrutiny: interdistrict open enrollment and guarantees.

Interdistrict open enrollment

More than 80,000 students today use interdistirct open enrollment to attend public schools in neighboring districts. Under current policy, the funding of open enrollees is fairly straightforward. The state subtracts the “base amount”—currently a fixed sum of $6,020 per pupil—from an open enrollee’s home district and then adds that amount to the district she actually attends. Apart from some extra state funds for open enrollees with IEPs or in career-technical education, no other state or local funds move when students transfer districts.

In a wider effort to “direct fund” students based on the districts and schools they actually attend, the Cupp-Patterson plan eliminates this funding transfer system for open enrollment. In the new plan, open enrollees receive the same level of state funding as resident pupils in that district—not a set amount that applies anywhere in the state. While this seems to make sense at face value, the approach results in significantly lower funding for most open enrollees relative to current law. The upshot: These reductions are likely to decrease participation in open enrollment, and they will remove valuable public school options for Ohio families and students.

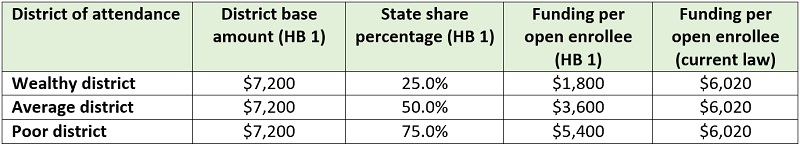

The table below illustrates how it would work. To ensure an equitable distribution of state money, HB 1 applies the state share percentage (SSP) to districts’ base amounts. Wealthy districts have a lower state share—they have the capacity to raise large sums locally—while the state picks up a larger portion of the tab in poorer districts. Applying the SSP to open enrollment funding would mean that a student choosing to attend a wealthy district might generate just $1,800 of state funds—instead of $6,020. While the SSPs are higher as wealth decreases, funding for open enrollees under HB 1 also falls below current levels when they attend average poverty districts and most high-poverty ones.

Table 1: Illustration of open enrollment funding under House Bill 1

Note: Base amounts are not determined by districts’ wealth and, with some exceptions, do not vary widely across districts. The statewide average base amount under a fully implemented plan is $7,199 per pupil. The state share percentage (SSP), however, varies by district wealth (property values and resident income) and ranges from 4.4 to 90.1 percent. Much like the current funding model, the SSP adjusts a district’s base amount for its local wealth to yield the state funding obligation for the core formula component.

The Cupp-Patterson approach to funding open enrollment would make sense if the state required the local share of the base amount to “follow” students to their district of attendance. But it doesn’t. The local funds designed for an open enrollee’s education stays in her home district. As a result, HB 1 significantly cuts open enrollee funding. These reductions not only underfund students’ education, but also drastically weaken the incentive for districts to accept open enrollees, especially high-wealth districts that could offer less advantaged students seats in their classrooms.

To address this problem, legislators have two options. First, they could revert open enrollment funding to the current model whereby all open enrollees receive the full base amount, whether that’s a fixed statewide amount or the one that applies to her district of residence or attendance. Though more politically challenging, lawmakers could alternatively require the local share of an open enrollee’s base amount to transfer from her home district to the district she attends.

Guarantees

Ohio has long debated “guarantees,” subsidies that provide districts with excess dollars outside of the state’s funding formula. These funds are typically used to shield districts from losses when the formula calculations prescribe lower amounts due to declining enrollments or increasing wealth. In FY 2019—the last year in which funds were allotted via formula—335 of Ohio’s 609 school districts received a total of $257 million in guarantee funding, representing about 2.5 percent of state K–12 education expenditures.[1] Worth noting is that the guarantee isn’t directly tied to poverty. A number of high-wealth districts benefit from the guarantee, including affluent suburban districts such as Brecksville-Broadview Heights, Mason, and Upper Arlington.

While guarantees may be politically convenient, they cause problems. For starters, they undermine the state’s funding formula, whose aim is to allocate dollars efficiently to districts that most need the aid. Districts on the guarantee receive funds above and beyond the formula prescription, while others must be content with the formula amount—sometimes even less. Many critics, including proponents of the Cupp-Patterson plan, have called this system unfair due to the piecemeal approach. Just as concerning is the way guarantees fund a certain number of “phantom students” when state money would be better used to meet the needs of real students.

Among the main ideas of the Cupp-Patterson plan is to create a fair funding system and to drive education dollars to the schools that students actually attend. Those are the right concepts and we might therefore expect the proposal to eliminate guarantees. Though the plan does make a slight improvement to the state’s guarantee structure, it does not put an end to it. In fact, Cupp-Patterson adds a few new measures that function just like guarantees. Consider the following:

All told, the Cupp-Patterson plan is a mixed bag on guarantees. On the one hand, it does transition Ohio to a per-pupil guarantee—a second-best option after eliminating them entirely. On the other hand, the plan takes two steps backwards with its subsidy for districts with large numbers of choice students and allowing for minimum staffing levels in its base-cost model.

***

Many of the concepts behind the Cupp-Patterson plan are commendable, but the translation of these ideas into concrete funding policies seems more questionable. The developers have aimed for a “fair funding” plan, yet still seem to treat the thousands of Ohio students exercising school choice options as an afterthought. And while its architects have also talked about funding all districts fairly—according to the state’s own formula—the plan continues to carve out special exceptions that deliver excess dollars to lucky districts. In the end, the plan’s details don’t always seem to square with its lofty ambitions. In the coming days, legislators should work to right these all-important details.

[1] Due to concerns about the current funding model, state lawmakers suspended the formula for FYs 2020 and 2021. In FY 2019, districts with declines in their “total ADM” (which includes district, charter, and scholarship students) between FYs 2014–17 were subject to state funding losses of up to 5 percent.

[2] This guarantee goes beyond temporary “hold harmless” provisions in HB 1 as the state transitions funding models. A permanent guarantee policy would start in 2024 and be in effect for every year thereafter. LSC estimates an annual outlay of $276 million in guarantee expenditures under a fully implemented plan, though it’s not clear whether that amount includes the costs of temporary guarantees during the phase-in period.

In 2013, President Obama made headlines for his visit to P-TECH, a Brooklyn high school created in 2011 through a partnership between IBM, the New York Department of Education, and the City University of New York. The innovative new school was designed to accomplish two goals: to provide students with a direct pathway to college attainment and career readiness, and to strengthen the local economy by helping build a workforce with strong academic, technical, and professional skills. Unlike a typical high school, P-TECH spanned grades 9–14. Students graduate with both a high school diploma and a two-year postsecondary degree, and participate in work-based experiences like mentorships and internships along the way.

In the years since President Obama’s visit, P-TECH’s Brooklyn campus has graduated four cohorts of students. The model itself has expanded to over 200 schools in eight states and several countries. More than 600 businesses have partnered with these schools, exposing students to a wide variety of career fields including health, IT, advanced manufacturing, and energy technology.

Given P-TECH’s popularity and success, it’s no surprise that Governor DeWine has expressed interest in bringing the model to Ohio. In his recently released executive budget, the governor allocated up to $450,000 over the course of two fiscal years for the creation of a P-TECH initiative in the Buckeye State. But how would it work?

Well, for starters, it’s a pilot program. Pilot programs are typically short-term, small-scale experiments aimed at testing whether a model is feasible and effective. That’s exactly what the governor has opted for with P-TECH. Only three schools will be chosen to participate in the pilot, and the funding they’re awarded must be spent within two years. The program would fall under the purview of both the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) and the Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE), though ODE would handle the distribution of funds.

If the governor’s P-TECH proposal gains legislative approval, the departments will be required to issue a request for proposals from interested applicants by September 1 of this year. That’s not a ton of time—just a few short months—and the tight timeline combined with the fallout of Covid-19 probably means that the list of applicants will likely be small. Fortunately, the eligibility requirements allow a pretty broad set of schools to apply. Traditional public districts, charter schools, STEM schools, and certain schools operated by Joint Vocational School Districts are all eligible.

The departments are charged with selecting the best applicants, but must give priority to schools that serve historically underrepresented populations of students, and must make “every effort” to select schools in different locations throughout the state. The proposed budget also explicitly outlines a list of criteria that eligible schools must meet. To qualify for funding, the proposed P-TECH model must:

The proposed timeline calls for three schools to be selected by October 2021. They will receive up to $150,000 in 2022 for planning activities (the budget outlines what these activities might include), and another $150,000 in 2023 to actually implement the P-TECH model with ninth grade students. Although schools will be evaluated based on the sustainability of their model, the money allocated for planning and implementation won’t replace other forms of state funding.

There are two additional provisions worth noting. First, the proposed budget builds on Ohio’s immensely popular College Credit Plus (CCP) program by allowing students to participate in CCP during any school year in which they’re enrolled in a P-TECH school. This should make it much easier for interested schools to meet the eligibility criteria related to providing dual-enrollment opportunities so students can earn an associate degree along with their high school diploma. CCP has been part of Ohio’s educational landscape for years now, so offering dual-enrollment options shouldn’t be a stumbling block for participation. The budget also removes some of the restrictions around CCP participation. For example, credit hour and duration limits that apply to typical CCP participants don’t apply to students who attend a P-TECH school. The budget doesn’t explicitly mention the readiness standards that other students must meet prior to enrolling in a college course through CCP. But it’s reasonable to assume that the departments will interpret the provision that allows all P-TECH students to enroll in CCP as an exemption from readiness standards.

Second, because P-TECH is set up as a pilot program, it would be under even closer scrutiny than similar programs. The departments are charged with evaluating the progress and sustainability of each model, as well as the partnerships between schools and businesses. They must report their findings to the governor and the General Assembly by December 21, 2022.

It's still early in the budget process, and lawmakers have a lot on their plates, so it’s hard to predict whether the governor’s P-TECH proposal will survive. But it’s an innovative program that’s proven successful elsewhere and would give both students and businesses a leg up. That’s exactly the kind of program lawmakers have supported in the past. Here’s hoping they do so again.

For more than two decades, report cards have offered Ohioans an annual check on the quality of public schools. They have strived to ensure that schools maintain high expectations for all students, to provide parents with a clear signal when standards are not being met, and to identify high-performing schools whose practices are worth emulating.

The current iteration of the report card uses intuitive letter grades—a reporting system that most Ohioans are accustomed to and support—and includes a user-friendly overall rating that summarizes school performance. In recent years, state policymakers have added new markers of success, including high school students’ post-secondary readiness and young children’s ability to read fluently.

While the current model can be improved, an ill-advised piece of House legislation (House Bill 200) goes in the wrong direction. It would gut the state report card—rendering it utterly meaningless—and cloak what’s happening in local schools. In short, the proposal would take Ohio back to the dark ages when student outcomes didn’t matter and results could be swept under the rug.

What does the bill do and why is it so bad? The bill:

Report cards are a balancing act. They must be fair to schools, offering an accurate and evenhanded assessment of academic performance. But they must also be fair to students—who deserve a report card system that challenges schools to meet their needs—and to parents and citizens who deserve clear and honest information about school quality. Ultimately, HB 200 veers too far in trying to meet the demands of school systems, which have an interest in a report card that churns out crowd-pleasing results—one that only captures “the great work being done in Ohio’s schools,” as the head of the state superintendents association recently put it. Such a system might avoid controversy, but it’s also a one-sided picture that ignores the interests of students, families, and taxpayers. As state lawmakers consider HB 200, they need to remember that report cards should be an honest assessment of performance, not simply a cheerleading exercise.

[1] HB 200 also takes a wrong either-or approach to value-added growth scores within the Progress component. The bill requires the use of either the three-year average score or the most current year score, whichever is higher.

School attendance is compulsory for K–12 students, but getting kids to school every day is often difficult for families. Most parents want their children to attend school. But for those living in poverty, competing needs like jobs, medical appointments, and sibling care sometimes render school a lower priority. This conundrum is on clear display in a new report from researchers at Wayne State University. The university is part of a citywide collaborative effort called the Detroit Education Research Partnership that focuses on K–12 student absenteeism as part of its ongoing work. Their latest report takes a close look at the barriers to attendance faced by students in Detroit—particularly those who are chronically absent.

It’s important to note that even before the coronavirus pandemic, absenteeism was rampant in Detroit Public Schools (DPS). Over half of the district’s students were considered chronically absent in 2019–20, missing more than 10 percent of the school year. The data in this new report come from interviews conducted before Covid-related school closures in early 2020. Researchers interviewed thirty-eight parents or guardians with students in seven DPS elementary-middle and high schools. About one quarter of those parents had children who were not chronically absent that year, and the remainder had children who ranged from moderately (missing 10–20 percent of days) to severely chronically absent (missing more than 20 percent). A second round of interviews consisted of twenty-nine high school students attending five district high schools. About a third of those were children of parents interviewed in the first round and the remainder were new participants. About a third of all the high schoolers interviewed were not chronically absent, and the rest ranged from moderately to severely chronically absent.

Transportation emerged as the most frequent and pervasive barrier to attendance. Previous research found that only 31 percent of K–8 students in DPS had access to traditional yellow bus transportation, eligibility requirements for which leave out most students living too close to their neighborhood schools, who must walk or take personal transportation instead. Also excluded are most students utilizing intradistrict school choice, who are denied transportation once they have opted for a school outside their neighborhood unless they are receiving certain services for special needs. No DPS high school students are eligible for yellow bus transportation, but they are able to ride city buses to school for free using their student IDs. Additionally, six individual schools operate their own supplemental shuttle-type bus services to transport those students denied yellow buses due to their proximity to school.

This patchwork of transportation eligibility and service—idiosyncratic down to the building—seems to have dissuaded families from relying on it even when eligible. Safety, reliability, and weather concerns combined to similarly dissuade families from using city buses or walking. Most parents and students surveyed relied upon personal vehicles. But more than a third of all Detroit families reported not owning a car in 2017, and respondents to the Wayne State survey reported very few backup options among their personal networks. If the family—or community—car broke down or was needed for another purpose, the value of school essentially dropped and an absence would typically result.

Students’ acute and chronic physical health issues, along with mental health and parental health issues, also created barriers to attendance. Surveyed parents expressed a strong understanding of the costs of missing school, but as in many cases of competing priorities, health seems to have won out over school. The researchers posit that post-Covid considerations will add a new wrinkle to this calculus. If classrooms are not considered safe enough, even the smallest roadblock could result in an absence.

The realities expressed by families resist easy solutions, especially school-focused ones. The researchers rightly call for more resources and creativity around student transportation. There are also likely lessons to be found outside of DPS—perhaps in Detroit’s robust charter sector or in Chicago’s “Safe Passages” program—but such efforts won’t fix all problems. A second recommendation to “strengthen neighborhood vitality” is a far heavier lift, as no concrete resources or avenues to success were identified.

Interestingly, the Wayne State researchers recorded but decided to omit a number of school-based reasons for absenteeism that were reported by respondents. They include unengaged students, teacher-student conflict, and conflicts between students. While the researchers argued that the out-of-school barriers were more prominent in their data, such in-school issues should not be overlooked. Motivated families and students will strive to overcome many difficulties to obtain what is valued. But if a long walk or an unsafe bus ride leads to a low-quality classroom experience or a schoolyard fight, staying home is a reasonable decision. Anything that can be done to boost the value of attending school could be enough to change the daily calculus. And let us not forget that the Covid era could be a silver lining for students: Increased access to the internet and one-to-one devices, along with a permanent online education option, could solve many of the absenteeism barriers identified in this report. But that, too, must be of high quality before families will value it.

SOURCE: Sarah Winchell Lenhoff, Jeremy Singer, Kimberly Stokes, and J. Bear Mahowald, “Why do Detroit Students Miss School? Implications for returning to school after Covid-19,” Detroit Education Research Partnership at Wayne State University (March 2021).

In school districts and charter school networks nationwide, instructional leaders are developing plans to address the enormous challenges faced by their students, families, teachers, and staff over the past year. To help kick-start their planning process, we are proud to present The Acceleration Imperative, an open-source, evidence-based document created with input from dozens of current and former chief academic officers, scholars, and others with deep expertise and experience in high-performing, high-poverty elementary schools. It has four key design principles:

Practitioners can download and use the document as a starting point or an aid for their own planning purposes. It’s in the public domain, with no rights reserved, so feel free to plagiarize it at will!

Click here to view and download the June 2021 version of The Acceleration Imperative. To buy a book based on these recommendations, see Follow the Science to School: Evidence-based Practices for Elementary Education.

NOTE: On March 16, 2021, the Ohio Senate’s Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on HB 67, a bill which would, among other provisions, make changes to the state’s graduation requirements in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy provided interested party testimony on the bill. These are his written remarks.

Thank you, Chair Brenner, Vice Chair Blessing, Ranking Member Fedor, and Senate Primary and Secondary Education Committee members for giving me the opportunity today to provide interested party testimony on House Bill 67.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

The last year has been incredibly challenging, as we’ve learned to live with Covid-19 and its many repercussions. As you know, education has been one of those areas impacted. Last March, students and teachers across the state were thrust into remote learning. Although a significant number of schools have reopened for in-person learning, the extended use of remote and hybrid models greatly reduced the number of student-teacher interactions.

House Bill 67 started off as an effort to suspend state assessments this school year. Its sponsors were forced to pivot when the Biden administration—echoing an earlier pronouncement from the Trump administration—announced that the U.S. Department of Education would not be granting waivers from the annual testing requirement of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). We support this decision and believe it’s more important than ever to know precisely where students are and to ensure that resources are directed to those communities most negatively impacted by the pandemic.

HB 67, as it now stands, seeks to minimize any potential negative impacts as a result of state assessments this year and to address a few logistical issues to make the testing process a little smoother. We support the move to extend the testing window to later in the school year and to push the timeframe for reporting results back a month. These are smart, commonsense adjustments.

Things get trickier as it relates to graduation requirements. We support the language in HB 67 providing additional flexibility to this year’s junior and senior classes. The classes of 2021 and 2022 are still by default subject to Ohio’s previous graduation standards which asked students to earn 18 points on a series of seven end of course (EOC) exams. Given those stringent requirements, extending the flexibility granted last year for these students is prudent.

However, HB 67 goes too far in allowing course grades to count for EOC credit for sophomores and younger. The graduation requirements for those classes were just modified by this body in 2019. Students in those classes are only required to pass two EOC exams—Algebra I and English II. To be clear, passing doesn’t even require a proficient score but only achieving “competency” which is in the “basic” range on the state assessment. If this year’s students struggled in these core classes, it’s important that they receive the extra supports they need to be successful and improve their performance. These courses are important markers for college and career success post high school and shouldn’t simply be waived.

Finally, while we aren’t opposed to eliminating the U.S. History EOC exam this year, we’d urge you to give the issue careful consideration. First, the U.S. History EOC exam can only help students. If they do well on it and their government EOC, they earn a citizenship seal—part of the new graduation requirements for the class of 2023 and beyond. There are no penalties or negative repercussions if a student performs poorly. Second, having an EOC exam on U.S. History is a statement of intent. It indicates that the state has prioritized the subject and thinks it’s important. These days an argument could be made that we need more emphasis on U.S. History—not less.

Thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony.