Three ways Ohio can improve education-to-workforce pathways

High-quality educational pathways that are closely aligned to in-demand, high-wage jobs are crucial.

High-quality educational pathways that are closely aligned to in-demand, high-wage jobs are crucial.

High-quality educational pathways that are closely aligned to in-demand, high-wage jobs are crucial. When implemented strategically and effectively, they can expand talent pipelines for employers, offer opportunities to adults who are struggling to navigate an ever-changing job market, help address readiness gaps, and give recent graduates solid routes into the workforce.

In a previous blog post, I examined Pathways Matter, an online tool from ExcelinEd that outlines a continuum of education-to-workforce policies. The framework is divided into six focus areas (such as postsecondary credential attainment and employer engagement), which break down into twenty recommended policies that offer on and off ramps to high-quality educational pathways for learners of all ages. ExcelinEd also analyzed the policy landscape of several states—including Ohio—to determine if and how they’ve implemented the policies on the Pathways Matter continuum.

Ohio’s case study identifies plenty of strengths, especially in the areas of postsecondary acceleration and workforce readiness, but there are also several areas where changes are needed. To Ohio’s credit, many of its weaker areas have already been addressed in some way. But if state leaders want to continue the trend of improvement, they’ll need to build on those foundations over the next few years. Here’s a look at three policies that, if implemented well, could have a significant impact.

1. Establishing a statewide audit of CTE programs for quality and equity

Ohio has several quality and equity policies already in place thanks to its state plan for Perkins V, the federal law that governs how states fund and oversee career and technical education (CTE). For example, the state has ten quality standards for CTE programs, and assists school districts and career-technical planning districts with quality program reviews. Since 2019, Ohio has offered equity labs for secondary CTE programs. Participants in these labs review data on access, engagement, enrollment, and performance; identify gaps in these areas; perform root cause analyses; and use their findings to create plans for change. The competitive Equity for Each grant program has made $1.5 million available to help identify and promote “promising practices” for improving equity.

These policies are a good start. But without a comprehensive system to monitor trends across sectors and geographic areas, state leaders can’t get the whole picture. A biennial and statewide quality and equity audit of CTE programs could meet that need. Such an audit would evaluate student access to and participation in quality programming; collect program- and student-level completion data and disaggregate it by career field, student subgroup, and geographic region; and ensure program alignment to high-skill, high-wage, and high-demand occupations. To be clear, Ohio likely already gathers much of this data. But it doesn’t use that data to uniformly evaluate quality and equity across all CTE programs and geographic regions, nor does it release those analyses in an easily digestible format for the public. The results of a statewide audit, on the other hand, would be publicly available in a biennial report. This report would give state leaders and stakeholders a common starting point, from which they could work together to address any identified gaps or weaknesses.

2. Improving industry engagement

Education-to-workforce pathways only flourish if there’s buy-in from the business community. Fortunately, Ohio already has a pretty solid foundation. State law requires every school district and education service center to have a Business Advisory Council to advise them on changes in the economy and job market and offer support on how to develop a working relationship with local businesses and labor organizations. The Ohio Industry Sector Partnership Grant funds collaboration between businesses, education and training providers, and community leaders interested in improving regional workforces. And Senate Bill 166, which was passed late last year, offers tax credits to businesses that provide work-based learning experiences for students who are enrolled in an approved CTE pathway.

There’s always room for growth, though, and ExcelinEd recommends that Ohio leaders consider offering additional incentives for employers to participate in work-based learning opportunities. For example, the Governor’s Workforce Board in Rhode Island oversees a Work Immersion program that helps employers train prospective workers through paid internships by reimbursing them at a rate of 50 or 75 percent for wages paid to eligible participants. In Kentucky, the staffing company Adecco partnered with the state department of education and twenty-one school districts to implement a work-based learning program. And in Delaware, a collaboration between education, business, and government leaders produced a statewide program that offers K–12 students the opportunity to complete a program of study aligned with an in-demand career. Each of these programs—or all of them—would be a positive next step for Ohio.

3. Reducing barriers to postsecondary credential attainment

Since state leaders announced a statewide attainment goal in 2016, Ohio has launched a plethora of initiatives aimed at improving credential attainment. TechCred helps Ohioans earn industry-recognized, technology-focused credentials and helps businesses upskill both current and potential employees. The Choose Ohio First Program, which was designed to strengthen Ohio’s competitiveness within STEM disciplines, provides participating colleges and universities with funding to support students in STEM and STEM education fields. And both the Individual Microcredential Assistance Program and the Ohio College Opportunity Grant help low-income Ohioans earn degrees and credentials.

Despite these developments, the state’s most recent annual report on attainment shows that there’s still plenty of work to be done. One way state leaders could further reduce barriers is to implement Last Dollar/Last Mile financial aid programs. These policies provide eligible students with state financial aid that fills in gaps left by federal assistance efforts (like Pell Grants), and promotes attainment for learners who are close to earning a degree. Several states already have such policies in place. For example, Tennessee provides recent high school graduates with a last-dollar scholarship through Tennessee Promise, and provides eligible adults who want to pursue an associate or technical degree or a technical diploma with a last-dollar grant via Tennessee Reconnect.

***

Ohio has made considerable strides in the last few years with its education-to-workforce pathways. There are dozens of new programs and initiatives aimed at increasing access to educational opportunities, improving attainment numbers, and strengthening Ohio’s workforce. But now isn’t the time for leaders to rest on their laurels. Let’s build on those developments, and implement the suggestions outlined above.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

The release of Ohio’s fall 2020 third-grade test scores last year—the first statewide exams since schools closed at the start of the pandemic—proved sobering, revealing substantial learning losses. At the time, Gov. Mike DeWine described the magnitude of the disruption as a “crisis.”

With an additional pandemic year under our belts, we now have new evidence on how much progress Ohio has made in making up lost ground. In a new report, I analyze the results from the fall 2021 administration of the state’s third grade English language arts assessment. Overall, the scores provide grounds for optimism, but also suggest that the students hit hardest by pandemic learning disruptions also made the least gains through the beginning of the 2021–22 school year.

On the positive front, although third graders started the current school year significantly behind pre-pandemic cohorts, the magnitude of the gap shrank by nearly two-thirds compared to a year earlier. Overall, third grade test scores in fall 2021 were about 0.08 standard deviations lower than the year before the pandemic, corresponding to being behind by between 1 and 1.5 months of learning. For some student subgroups—including English learners and students with disabilities—achievement has largely recovered to the pre-pandemic levels of similar students.

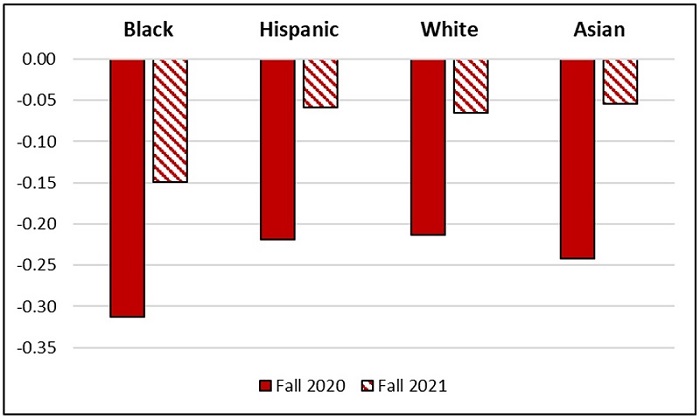

Nevertheless, considerable gaps remain, especially among some of the most disadvantaged populations. Test scores of African American students remained 0.15 standard deviations lower in fall 2021 compared to this group’s pre-pandemic baseline, nearly double the size of the shortfall observed among their white peers. African American students also appear to have made up a smaller share of the initial learning losses, cutting the learning loss by about half compared to at least two-thirds for the other racial and ethnic student groups. In addition, the gap in urban districts remains larger than for other types of school systems.

Figure 1: Achievement losses compared to pre-pandemic cohorts, fall third grade ELA exams

And though all school systems have now largely returned to full-time in-person learning, the previous modes of instruction available to students remain associated with the impact of the pandemic on achievement. Students attending districts that spent most of last year (2020–21) in virtual learning continued to post lower average scores in the fall of the current school year.

These results are largely congruent with those of a recently released national study, which also found much larger learning losses in districts that remained closed to in-person learning for much of 2020–21, along with a growing racial achievement gap.

It is important to keep several important caveats in mind. First, Ohio’s fall exams cover only one grade and subject (third grade reading). As we saw last year, the impacts on spring math scores were generally larger on average than in reading, but the differences between student subgroups were also smaller. Second, the fall exams were completed prior to the Omicron wave in December and January, which resulted in widespread student and teacher absences and disrupted learning substantially for many. In sum, we’ll know more about recovery when spring 2022 test scores are released in the fall.

The results of the fall exams highlight the tremendous energy and resources teachers, school districts, and other public leaders have invested on academic recovery in Ohio—but also the uneven results from these efforts. Apparently due to both teacher and parent opposition, for example, local school districts have largely avoided increasing learning time by extending the school day or school year. Yet this is likely to be the only intervention that can deliver sufficiently large gains at scale and reach the students who need help the most, as Harvard economist Thomas Kane has noted recently.

Instead, districts have pursued a hodgepodge of different strategies and initiatives, offering optional summer programs and after-school tutoring. The problems with such opt-in efforts are two-fold. First, such programming is likely to attract an unrepresentative and unusually motivated group of students and families, potentially risking leaving the most at-risk, disadvantaged students behind. As the former head of Ohio State’s first-year experience program—himself a first-generation college graduate from Appalachia—told me many years ago, students who need additional support the most “don’t do optional.” Second, because motivated students who choose to participate would have probably made especially large learning gains regardless, such services are incredibly difficult to evaluate convincingly. Without credible evidence on what works, we are likely to waste considerable time and public resources on ineffective programming. Yet local districts appear to have largely prioritized exactly these kinds of optional programs in their recovery efforts.

The current school year has also revealed the operational challenges that continue to plague schools across Ohio and disrupt student learning. Many districts struggled with inadequate substitute coverage even before the Omicron wave, and a shortage of bus drivers has made school transportation a particularly acute chokepoint. With labor shortages continuing and new Covid variants combined with waning immunity likely to lead to new surges in the fall and winter, it is essential for all stakeholders and public officials to come together to develop contingency plans now, ahead of the coming year, so that we continue the work of getting Ohio students back on track.

Vladimir Kogan is Associate Professor in The Ohio State University’s Department of Political Science and (by courtesy) the John Glenn College of Public Affairs. The opinions and recommendations presented in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of the John Glenn College of Public Affairs, the Department of Political Science, or The Ohio State University.

Since the start of the pandemic, Ohio schools have received more than $6 billion via three federal relief acts. The vast majority of these funds were distributed directly to schools using Title I formulas, but officials also reserved a chunk for state-level efforts to support schools.

One such effort is the Summer Learning and Afterschool Opportunities Grant. This competitive grant program is designed to fund partnerships between schools and community-based organizations to establish or expand afterschool programs, as well as summer learning and enrichment programs. The Ohio Department of Education (ODE) began accepting grant applications in February. In late April, ODE announced that after receiving over 700 applications, 161 community-based partners would be awarded $89 million. The grant period lasts through September 2024, so it’s far too soon to gauge their effectiveness. But the state’s request for applications (RFA) offers a sneak peek at a few things to expect from grantees.

First and foremost, the RFA notes that grant-funded services must be provided when school is not in session. Examples of potential programming include (but are not limited to) reading and math tutoring, mentoring, wellness activities, summer camps, bridge programs for students transitioning to the next grade level or to postsecondary education, career pathways programs, pre-apprenticeships and registered apprenticeships, credit recovery or advancement, and learning opportunities that occur at museums, zoos, and libraries.

Second, programs must be “uniquely designed” to meet the local needs of students, especially those who have “experienced disruptions to learning and did not engage consistently in school during the pandemic.” Funding priority was given to applicants who partnered with priority and focus schools—those that, under federal school identification guidelines, are implementing comprehensive or targeted support and improvement activities due to poor performance—and applicants who proposed serving students in geographic areas where there is a lack of existing out-of-school programming. Grant awardees can serve students of any age, including preschool.

Third, any program that’s established or expanded using these grant dollars must be evidence-based. Guidance from the U.S. Department of Education (as well as the Evidence Based Clearinghouse managed by the Ohio Department of Education) identifies four levels of acceptable evidence. The definition of “evidence-based” is fairly broad, but the requirement encourages recipients to be more thoughtful about which programs they implement.

Grant funding was divided equally between afterschool and summer programming. Some awardees have already released information about the opportunities they’ll be offering over the next few years. For example, the Lake Erie College School of Education and Painesville City Local Schools partnered to create the Afterschool Enrichment Program. Their grant, which totals more than $998,000, will serve 75 to 100 students in grades K–6 on week nights from 3:00 to 7:00 p.m. and will provide a “variety of enrichment opportunities,” including math and literacy tutoring, a social and emotional wellness program, reading to dogs (whereby students practice their reading skills with furry companions) and community outreach and service projects. The Great Lakes Community Action Partnership joined forces with Fremont City Schools to create both summer and afterschool programs. And the Champaign Family YMCA received a total of $2.1 million, and will partner with the Graham Local School District to expand afterschool programming, expand summer programming for middle and high school, and create a summer program for elementary school.

Devoting a portion of federal relief dollars to out-of-school efforts like these was a wise move, as effective programs can help decrease the impact of pandemic-caused learning loss, improve students’ social and emotional growth, and provide working parents with a safe and engaging environment for their children. Now the focus must turn to implementation, including encouraging students who could most benefit from these services to sign up, and to identifying effective programs that are worthy models for future investment.

In the spring of 2020, a group of researchers from the University of California San Diego was engaged in a longitudinal study of changes in young children’s learning experiences during kindergarten and first grade at an anonymous, medium-sized, socioeconomically diverse school district in southern California. Two weeks after the initial suspension of schooling in March 2020, the caregivers in the larger study were invited to participate in a different project, which would use a remote daily diary protocol to collect information on family life, including their children’s educational activities, under lockdown.

Thirty-two primary caregivers with a child in kindergarten agreed to participate. The majority were mothers; 44 percent of the parent-child dyads identified as Hispanic, 34 percent as white, and 22 percent as mixed race. The children were six and a half years old on average. About a third of the dyads came from Spanish-speaking homes. Families came from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, with 25 percent from the lowest income group (earning less than $50,000 annually), 22 percent from the middle-income group ($50,000–$75,000), and 44 percent from the highest income group (greater than $75,001). Fifteen percent did not fully answer the income questions and could not be classified.

Families were prompted via text message to fill out a survey instrument five times per day over the course of five days at two different time points. The first survey wave was given three weeks after the district launched its virtual learning platform via Google Classroom, and the second wave was given four weeks later, in the second-to-last week of the school year. Messages were sent at random times throughout the day from 7:30 am to 9:00 pm for five consecutive days. Each text message included a link to the researchers’ five-minute survey, and participants were asked to complete it as close as possible to the time they received the text message. The link expired after one hour to help boost timely compliance. Parents primarily responded to surveys outside of school hours and mostly while they were with their children, which aided the analysis.

While the analysts framed their research interests in further detail in the report, they boil down to questions regarding what children and families were doing all day, whether caregivers ascribed positive or negative value to these activities, and whether caregivers were happy with the activities. They hypothesized that socioeconomic status of the family would likely impact the answers.

The majority of the time, children were reported to be with at least one parent. About half the time, children were also with at least one sibling. When not with a parent, children tended to be with a sibling, playing or sleeping alone in a room while the parent was in another part of the house, or with another relative. Low-income families were more likely to report that they were with their child at the time of responding to the text survey than were middle- and high-income families. Primary activities reported were mealtime, chores, educational activities, sleeping/resting, play, outside time, and technology use.

Children’s technology use time was primarily occupied by remote schooling (41.4 percent)—non-district educational activities occupied another 18.3 percent of tech time—followed closely by watching TV (36 percent). Parents were significantly more likely to be involved in educational activities on weekdays when they were with their child and less likely to be involved in educational activities on weekends. While parental activities reported did not vary with family income, children’s activities did. Low- and middle-income children were more likely than high-income children to be engaged in mealtime activities. Middle-income children were marginally more likely to be engaged in chores than high-income children. High-income children had higher rates of being outdoors than middle-income children. And low-income children were more likely to be engaged in an activity that included technology than middle- or high-income children.

Overall, caregivers reported high levels of enjoyment in their own activities and even more in their children’s activities. They reported feeling positive emotions a majority of the time (66 percent), followed by overwhelmed emotions (18 percent). Parents only reported a negative emotion in three percent of their responses. Low-income parents reported having more positive emotions than did their high-income peers. In general, caregivers attributed their emotional states, both positive and negative, to unspecified “personal experiences” or to the activity they were participating in at the time of reporting. Their emotional states were attributed to their children’s experiences 21 percent of the time. Parental enjoyment was correlated with children’s enjoyment and with children’s activities deemed to be building social skills. Notably, neither parent nor child enjoyment were associated with activities appraised as building academic skills.

What are we to make of all this? While it is a limited snapshot of a handful of families in the earliest weeks of the pandemic, the positivity expressed almost across the board is very clear. The families surveyed appeared to be going about their lives with as much normality as they could muster given the upheaval around them. If anything, the picture is a somewhat quaint one of generations living and interacting together more often and more fully. If parents were fearful of short- or long-term employment or educational disruptions at the time, it did not register in these detailed surveys. Like most of us, they likely believed the situation to be temporary, even two months into the plague. But when it ceased being temporary—similar research could likely pinpoint the timing and the catalysts—the positivity ebbed as learning loss and economic disruption became obvious and quantifiable.

SOURCE: Shana R. Cohen, Alison Wishard Guerra, Monica R. Molgaard, and Jessica Miguel, “Social Class and Emotional Well-Being: Lessons From a Daily Diary Study of Families Engaged in Virtual Elementary School During COVID-19,” AERA (May 2022).

Providing transportation for students to and from school is a basic requirement of most public school districts in America. During the 2018–19 school year, nearly 60 percent of all K–12 students nationwide, public and private, were transported by those ubiquitous yellow buses. In some states—such as Delaware, Mississippi, and Alaska—those numbers were nearer 100 percent. A research team led by Temple University’s Sarah Cordes wanted to both quantify bus commutes for students and to see if there was any connection between transportation, absenteeism, and achievement.

This is a new area of research, and while not representative of other cities, New York City’s transportation data was detailed and easily accessible. So Cordes and her team started there, looking at data from New York City from 2011 to 2017, examining the commuting patterns of more than 120,000 bus riders in grades three through six. They include travel to school in the morning only and exclude bus routes specifically for students with special needs and those that serve multiple schools nonsequentially (i.e., students from School B are picked up before students from School A are dropped off). The final sample comprises more than 90 percent of all morning bus routes and, despite the robust public transit system in the city, includes 89.4 percent of all students in grades three through six attending district and charter schools over the period.

The average bus ride is relatively short—approximately twenty-one minutes from pickup to drop off—with 75.8 percent of students having rides shorter than thirty minutes and more than 90 percent having rides shorter than forty-five minutes. None of these figures includes the non-bus portion of a morning commute—walking to a stop, waiting for the bus, loading/unloading, and waiting for school to start (for those kiddos who arrive early). Including these factors, the average commute balloons to more than fifty minutes.

There is, as one might suspect, a disparity in ride duration for students opting for intradistrict school choice or charter schools. And it is a big one. Students attending their zoned district school ride a bus for an average of just under thirteen minutes each morning, while students attending a district school of choice ride for more than twenty-four minutes and students attending a charter school ride for nearly twenty-six minutes on average. And accounting for total commute, the gap in travel time between zoned school and choice school attendees is enormous—thirty-eight minutes to nearly sixty minutes, respectively.

Interestingly, the average student in NYC lives 2.13 miles from her school and would likely be able to walk or bike there in a far shorter amount of time than commuting by bus, if such options were feasible—which they often are not, due to safety concerns, family commitments, and a lack of easily-traversable routes.

But is a long bus ride problematic for kids? To answer that question, Cordes and her team focus in on a subset of 489 students in 2017 (3.1 percent of the total sample for the year) who experienced a bus ride of more than one hour. More than 95 percent of those long riders were utilizing school choice to attend a building that was not their zoned school. More than 47 pecent were Black, and just less than 11 percent were white.

Initial analysis shows that students with very long bus rides outperform those with short bus rides on math and reading exams by between 0.02 and 0.11 standard deviations. But the analysts suspected that choice students would likely be more motivated than their zoned school peers (accepting the long ride as a tradeoff for a better-fitting school) and/or were attending magnet schools as part of the district’s gifted and talented program. When such positive selection factors are controlled for, test score impacts disappear and slight negative attendance impacts appear. Students with bus rides over one hour long had 0.3 percentage point lower attendance rates and 1.9 percentage point higher chronic absenteeism rates than their peers. These effects are concentrated among choice students rather than the handful of zoned school students who happen to have a very long commute. Thus, the tradeoff to take advantange of choice becomes more negative than is immediately obvious.

In New York City, district-provided school transportation appears to work pretty well for most students who use it, with long bus rides and negative effects being small and concentrated. While New York is not representative of other places in a number of respects, choice students having longer and more difficult commutes than traditional district students is a common situation. If we are interested in shortening all bus commutes to the absolute minimum and in reducing the inequity between choice and district students in this regard, even NYC’s atypical data show that some modern updates to the quaint old district-controlled yellow bus might be in order.

SOURCE: Sarah A. Cordes, Christopher Rick, and Amy Ellen Schwartz, “Do Long Bus Rides Drive Down Academic Outcomes?” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (May 2022).