GUEST COMMENTARY: Is a 10th grade education too high a bar for an Ohio diploma?

By Tom Gunlock

By Tom Gunlock

NOTES: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

This piece was originally published in the Dayton Daily News.

When you ask most people, “What should a high school diploma represent?” They’ll tell you, “It means a student has a 12th grade education.” If only that was the truth. Unfortunately, in Ohio, it’s not.

This year’s diploma recipients will have completed 15 required high school courses and at least five elective courses. The required courses include four years of English, four years of math, three years of science, and three years of social studies. In addition, students will have scored proficient on the five sections (reading, writing, mathematics, science and social studies) of the Ohio Graduation Test. The dirty little secret, though, is that the Ohio Graduation Test is a test of 8th grade knowledge. Do most students graduate with more than an 8th grade education? Of course. But an 8th grade education is the minimum.

Back in 2010, Ohio made a decision. An eighth grade education isn’t enough. An eighth grade education is not enough for our students to succeed in what comes after high school – life, further education, and career. It’s not enough to ensure the continued economic success of our communities and our state.

Researchers that study the changing nature of the U.S. workforce say loudly and clearly that today, and into the future, more and more people will need some education past high school to get a job that pays a living wage and leads to a life-sustaining career. That doesn’t mean a student has to go to college – it could mean a certificate program, an apprenticeship, or an employer training program. One thing is clear; you cannot make a living or build a career working a minimum wage job! And yet, for too many young Ohioans a minimum wage job is where they’re headed with the equivalent of an eighth grade education.

In 2010, Ohio set in motion higher standards, and the expectation that in order to earn a diploma students should demonstrate at least a 10th grade level of learning to earn a diploma. Our districts and schools have known this for 6 years, and the expectation is that they have been ramping up and providing the educational experiences necessary so that this year’s junior class can be the first class to meet this higher standard. In addition to taking the required courses students will need to take seven tests over the four years of high school (instead of the five test required previously). These are tests of freshman and sophomore level English, freshman and sophomore mathematics (Algebra and Geometry), American History, American Government, and Biology.

If you think about it, it doesn’t really seem to be so daunting. During the four years, a student is in high school, they’ll take at least four years of English. You’d think that educating a student sufficiently to pass tests of freshman and sophomore level English should be pretty easy. Similarly, students will have to take four years of math courses. Is it unreasonable to expect students to acquire the knowledge and skills needed to pass Algebra I and Geometry tests by the end of four years? The remaining tests, American Government, American History and Biology are subjects that have been required courses for years. Students have multiple opportunities to take each test. And students don’t even have to score at a proficient level on every test. Let me tell you what the cut scores are for each of the 7 tests.

Only one of those cut scores has a cut score greater than 50%. Each and everyone of them would be an F in any classroom in this state.

How are some school districts reacting to this reality? The districts most committed to students are saying, “We agree with the standards and the assessments. We’re taking this issue seriously, and we’re putting in place what’s needed to help our students meet these higher standards. We’re going to do whatever it takes to support students reaching the requirement.” Districts in this category represent the best kind of no-excuses, get-it-done attitude and commitment that reflects what makes Ohio great. It reflects an understanding that our students are certainly up to the task, and our teachers, schools and administrators are up to the challenge too. Some of these districts make the case that Ohio may need a longer transition to meet the standard. The need for a little more time might be something worth exploring.

At the other end of the spectrum are districts that say, “The sky is falling! 40% of our students won’t graduate. We’ll have a lot more students without diplomas – and you can’t even get a Walmart job without a diploma.” They’ll go on to tell you that the tests are too hard, and they simply don’t know what to do to help students reach these higher levels. They might even suggest that students simply can’t reach this higher bar. Not everybody needs Algebra, right? Who really uses Geometry, or Biology?

This perspective misses the whole point. It places more importance on the symbolism of the diploma rather than the learning it should stand for. That view adopts the worst kind of defeatist attitude that undervalues the capability of our students, and, frankly undervalues the capabilities of the teachers and professionals that every day commit themselves to providing the best educational opportunity possible. It closes doors for students at a time when we should be making every possible future pursuit a viable one.

Perhaps what is most encouraging is that Ohio’s been in this kind of situation before. When the Ohio Graduation Tests were first implemented, we had some schools and districts sound the alarm that many students wouldn’t graduate. But we got it done – because educators, state government, communities, and partners all worked together to identify the strategies and actions that needed to be taken to get there.

What happens if we decide it’s just too hard? Businesses will continue to struggle to find workers with the knowledge and skills to do the increasingly complex work that represents the new normal. They’ll go elsewhere to places that can meet their workforce needs. Colleges will continue to enroll students who can make it through the front gate, but don’t have what it takes to cross the finish line. The patterns we see today of high levels of students dropping out of college with high debt and no hope of having the means to repay will continue.

Our students deserve better. Yes, it will be hard work. Yes, it will push all of us outside our comfort zones. We know that the conditions aren’t always ideal for change to occur. We’ll find strength in working together and supporting each other, and knowing that the work we do will create hope – hope for our students, hope for our communities, and hope for the future of our state. Let’s commit ourselves once again – educators, state government, communities, and partners of all varieties – to do what we know can be done. Our children and future generations will thank us.

Tom Gunlock is a Centerville businessman who served six years on the State Board of Education of Ohio, including two as president. He left the panel earlier this year.

“Government by the people” is one of the most powerful ideas in American government. It represents the belief that, in a democracy, the people hold sovereignty over government and not the reverse.

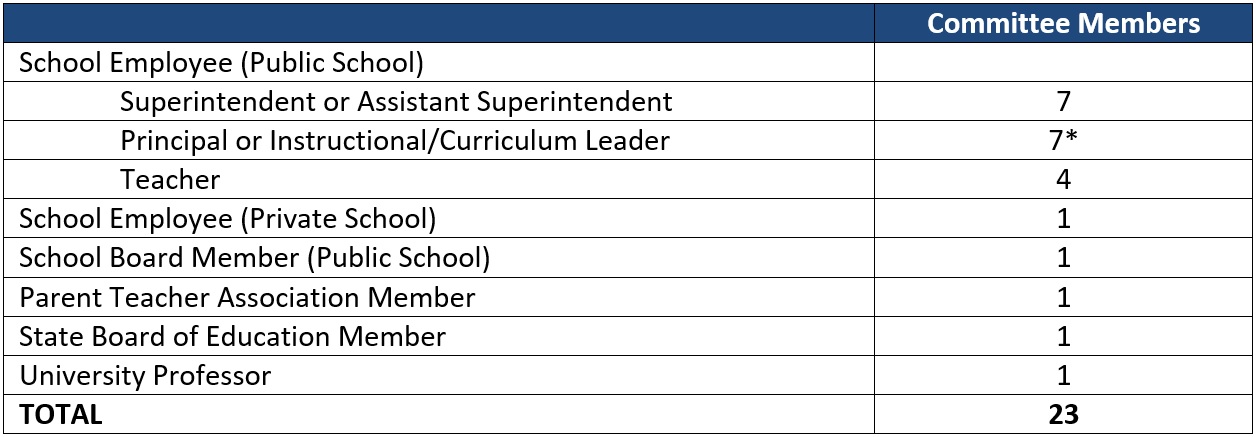

I bring this up as a way of considering how far we can deviate from this ideal. Take a look at Ohio’s newly formed assessment committee, which is charged with the important task of reviewing assessment policies. While this is an “advisory” committee with no formal policymaking authority, one expects its recommendations to make headlines and capture legislator attention. The state superintendent recently appointed twenty-three committee members and it’s almost entirely comprised of government (i.e., public school) employees. As you can tell from the table below, public school administrators, principals, and teachers hold eighteen of the twenty-three seats—a large majority.

* One member is considered tentative

Administrators and teachers should definitely be part of this conversation. But it’s not right to stack this committee with public employees whose own interests are also at stake. For instance, it’s no secret that many school officials want to weaken Ohio’s assessment and accountability policies. One reason: Their lives get easier when the state waters down assessments (and accountability based on them). Under an “A’s for all” approach, they’ll surely face fewer nosy questions from their boards, parents, and community members about how well their schools are preparing kids for college and career. It may even increase the likelihood that levies pass and lead to pay raises for them and their staff.

It’s a shame that this committee couldn’t have been more representative of families, taxpayers, and employers. They too have a stake in how Ohio assesses and reports student learning. Parents have an interest in their own kids’ state test scores, as well as how their school handles matters of state (including test prep) and local assessments. Taxpayers, more broadly, also have an interest in assessment and accountability policies. Given the amount we spend on K-12 education—roughly $20 billion per year in local, state, and federal dollars—they deserve honest gauges of how students and schools are doing based on objective achievement data. Finally, Ohio’s employers should be an engaged partner in this conversation as well. They rely on a strong K-12 school system to meet their workforce needs in a competitive, global marketplace. Understanding this, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has been one of the staunchest advocates of higher standards and strong accountability policies.

Assessment and their related accountability policies affect Ohioans everywhere. Yet the recently formed review committee doesn’t reflect a wide spectrum of voices. It’s almost entirely comprised of public employees with their own narrow interests. Whatever the committee recommends this summer should be taken with a hefty grain of salt.

Research on individualized, in-school tutoring such as Match Corps has demonstrated impressive results. A report from the Ohio Education Research Center examines a tutoring intervention developed by Youngstown City Schools and Youngstown State University to help more students meet the test-based promotion requirements of Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee.

Called Project PASS, the initiative enlisted almost 300 undergraduate students who weekly tutored second and third graders outside of regular instructional time. Each undergrad committed thirty hours per semester and received course credit and a small monetary award in return. The tutors received training and used a variety of reading strategies. The evaluation includes about 300 students who participated in one or more semesters of PASS from spring 2015 (second grade) to spring 2016 (third grade). The evaluation was not experimental, and the self-selection of students into PASS limits the ability to draw causal inferences, as the authors note. Nevertheless, the researchers were able to match participants and non-participants based on demographic and prior achievement data (using a second grade diagnostic test given before program launch) to compare test score outcomes.

The results indicate that the tutoring increased their state test scores in third grade reading. PASS participants scored significantly higher than non-participants on the reading part of their spring 2016 third grade ELA exam. The higher scores translated to an increased likelihood of meeting the promotion requirements of the Third Grade Reading Guarantee by 29 percentage points. Interestingly, the positive results were largely driven by participants who had also received tutoring in prior semesters (e.g., fall 2015 and spring 2016). However, for “new” PASS participants—those in the program only that spring—the gains were smaller and not significant.

The analysts conclude, “It may take students time to acclimate to PASS tutoring before they reap rewards in the subsequent semester.” That sounds right. Students who stick with the program—and receive higher dosages of tutoring—stand to benefit the most. Hopefully, the university and school district can also sustain what sounds like a promising partnership, while other communities without a program like this might just take a look and see what Youngstown is doing.

Source: Adam Voight and Tamara Coats, Evaluation of Grades 2 and 3 Reading Tutoring Intervention in Youngstown, Ohio Education Research Center (2016).

Secretary DeVos can be explained and forgiven—especially in these wee early days of her tenure—for bringing many of her public statements back to the theme of school choice. After all, that was President Trump’s one big education idea on the campaign trail, and the public-policy cause to which DeVos has dedicated her life.

And yet.

There’s a saying that when all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. Team DeVos loves the hammer called school choice. (I do, too!) But they could use a few more tools in their toolbox, lest they cause some serious damage to the construction project we call school reform. Secretary DeVos: May I offer you a screwdriver?

The trouble started with her White House comments to presidents of Historically Black Colleges and Universities. These postsecondary institutions were “pioneers for school choice,” she said in prepared remarks. “Tone deaf,” Representative Barbara Lee (D-CA) tweeted. “HBCUs weren’t ‘more options’ for black students. For many years they were the only options.” The DeVos team soon walked it back.

But, it didn’t stop there. A week later, when speaking to the Military Child Education Coalition, she praised America’s servicemen and women “for joining the military with the express purpose of having access to the Department of Defense’s excellent schools—a patriotic form of school choice if I’ve ever seen one.” (The 74’s Matt Barnum was rightly skeptical, pointing out that most recruits enlist at age 18, long before becoming parents to school-age children.) She complicated matters by asking “why we should restrict the DOD schools only to military personnel” and called on Defense Secretary Jim Mattis to “tear down this wall” that keeps non-military children out of these “excellent educational institutions.”

Diplomatic relations were not improved when she addressed a group of education ministers from the member nations of the Organization for Economic Development (OECD) a few days later. “There’s little doubt,” she argued, “that the many migrants moving around the world are a classic example of pro-school choice parents voting with their feet.”

DeVos didn’t stay for questions and the Trump administration refused to comment. Moreover, she wasn’t seen or heard from for nine days.

DeVos re-emerged this Wednesday for a keynote address at the Association of Title IX Administrators. “Why do we insist on perpetuating the myth,” she asked the audience, “that the growth in women’s athletics was due to a federal regulation? Long before Title IX there was school choice, in the form of all-girls schools, and those girls, let me tell you, knew how to play a mean game of field hockey!” The crowd, initially silent for what seemed like ages, eventually erupted into heckles and boos. Her Secret Service detail rushed her off stage and into a black SUV, wherein she made an escape.

To be sure, advocating for school choice is an important, and legitimate, part of Secretary DeVos’s job. Particularly if President Trump’s $20 billion school choice proposal is to get traction in Congress, it’s going to take consistent persuasion and leadership from the top. But if DeVos is truly going to break some glass, and make real change, she needs to give her hammer a little bit of rest.

The manner in which Ohio funds charter schools is controversial and is a serious contributing factor to the antipathy felt toward them. Traditional public school districts argue that Ohio is “taking money away,” even going so far as to invoice the state department of education for the money they feel they’ve “lost” to charter schools. This is one way of increasing publicity around Ohio’s imperfect funding system, but it also fuels misperceptions about how charter funding works and increases hostility between the sectors. It also belies the notion that the state funds children, not buildings or staff positions.

In a recent Fordham paper done in conjunction with Bellwether Education Partners, “A Formula That Works: Five ways to strength school funding in Ohio," we recommend doing away with Ohio’s current method of indirect funding. This approach has state dollars for charter schools “pass through” districts—thus appearing to be a subtraction from their bottom line. The reality is far more complicated and has been explored in previous Ohio Gadfly posts, like “’That’s not how this works!’ – correcting the rhetoric around public charter schools” and “Straightening the record on charters and local tax revenue.”

Take a look at our animated briefing, “Ohio Charter School Funding: Confusing and Controversial.” It explains how funding works for both districts and charter schools and why there is so much confusion around how charters are funded. It also shows why some can be lead to think that charters receive more per pupil funding (they don’t) or “steal” local funding from districts (again, they don’t). Charter schools receive about one third less in total—considering state, local, and federal revenue—than their traditional counterparts, despite serving students who are predominantly low-income and/or students of color.

Ohio’s current method of funding charter schools—and schools of choice more broadly, for that matter—is confusing, inefficient, and creates controversy rather than collaboration. For these reasons and more, it’s time that Ohio lawmakers consider direct funding.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, CHECK OUT OUR RECENT RESEARCH REPORT ON SCHOOL FUNDING IN OHIO:

School funding policies continue to be a subject of intense debate across the nation. Places as diverse as Alabama, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Maryland, and Washington are actively debating how best to pay for their public schools. According to the Education Commission of the States, school finance has been among the top education issues discussed in governors’ State of the State addresses this year.

States have vastly different budget conditions and a wide variety of policy priorities. No one-size-fits-all solution exists to settle all school funding debates. But there is a common idea that every state can follow: Implement a well-designed school funding formula, based on student needs and where they’re educated. Then stick to it.

A recent study commissioned by Fordham and researched by Bellwether Education Partners looks under the hood of Ohio’s school funding formula. Our home state’s formula is designed to drive more aid to districts with greater needs, including those with less capacity to generate funds locally, increasing student enrollments, or more children with special needs. In large part, Ohio’s formula does a respectable job allocating more state aid to the neediest districts. According to Bellwether’s analysis, the formula drives 9 percent more funding to high-poverty districts. This mirrors findings from the Education Trust which also found that Ohio’s funding system allocates more taxpayer aid to higher poverty districts.

Still, the Buckeye State has much room for improvement in its funding policies. And it’s worth highlighting three lessons from the study, as they illustrate challenges other states might face when designing a sound funding formula.

First, states should allow their formula to work—and not create special exceptions and carve outs. Our study found that the majority of Ohio districts have their formula aid either capped or guaranteed, meaning allotments are not ultimately determined by the formula. Instead, caps place an arbitrary ceiling on districts’ revenue growth, even if they are experiencing increasing student enrollment. Conversely, guarantees ensure that districts don’t receive less money than a prior year—they “hold harmless” districts even if enrollment declines. While caps and guarantees may be necessary during a major policy shift, allowing them exist for perpetuity, as Ohio does, undermines the state’s own formula. Ideally, all districts would receive state aid according to a well-designed formula. They shouldn’t receive more or less dollars through carve outs such as funding caps and guarantees.

Second, policymakers in choice-rich states need to make clear that funds go to the school that educates a student—and not necessarily her district of residence. Ohio has a wide variety of choices, including more than 350 charter schools, several voucher programs, and an inter-district open enrollment option. Yet the state takes a circuitous approach to funding these options, creating unnecessary controversy and confusion. The state first counts choice students in their home districts’ formula and then funds “pass through” to their school of choice. This method creates the unfortunate perception that choice pupils are “taking” money from their home districts, when in fact the state is simply transferring funds to the school educating the child. (For more on Ohio’s convoluted method to fund schools of choice, check out our short video.) To improve the transparency of the funding system in Ohio, we recommend a shift to “direct funding.” Under such an approach, the state would simply pay the school of choice without state dollars passing through districts.

Third, states should ensure the parameters inside the formula are as accurate as possible. Ohio, for example, faces a problem when assessing the revenue-generating capacity of school districts. A longstanding state law generally prohibits districts from capturing additional revenue when property values rise due to inflation, unless voters approve a change in tax rates. But this “tax reduction factor” is not accounted for in the formula, leading to an underestimation of the state’s funding obligations. Solid gauges of property and income wealth, along with sound measures of enrollment and pupil characteristics, are essential ingredients to a well-designed formula.

The realm of school finance is vast, encompassing a seemingly endless number of challenges. We don’t cover it all in this one report. But state policymakers would be wise to focus on the design and implementation of the school funding formula. It’s a key policy lever in efforts to create a fairer and more equitable funding arrangement for all students, regardless of their zip code or school of choice. Creating a solid formula—and ensuring its use—is hard work, but it might be our best bet for settling the debates over school funding.