Ohio charters are speeding ahead in the post-pandemic enrollment competition

One of the big stories in the wake of the pandemic has been the nationwide slump in public school enrollments.

One of the big stories in the wake of the pandemic has been the nationwide slump in public school enrollments.

One of the big stories in the wake of the pandemic has been the nationwide slump in public school enrollments. From fall 2019 to 2021, public school enrollment nationally fell by 1.2 million students, or a loss of 2.5 percent. Various factors explain the slide, including more parents opting for private schools or homeschooling, as well as continuing declines in the overall number of school-aged children given the recent baby bust.

As previously discussed on this blog, Ohio’s public school enrollments also fell sharply during the pandemic. This piece looks at the most recent numbers from the 2023–24 school year. Has enrollment continued to slip, or is it starting to turn upward? Are there differences in trends across various regions of the state, or by district and charter school sector? Student enrollment numbers and trends are important, as they offer a window into parents’ school preferences and impact key policy areas like school funding.

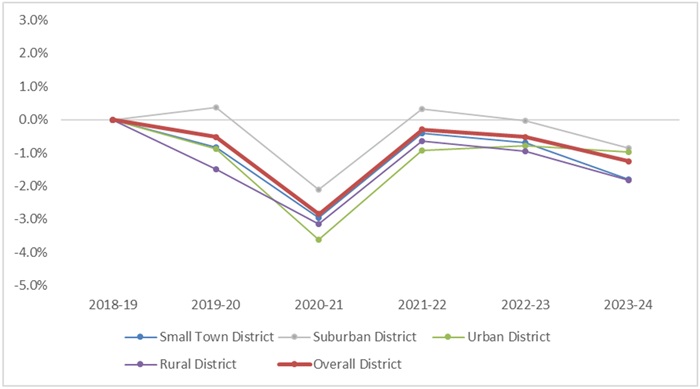

Let us begin with a look at traditional districts, excluding public charter schools for now. Figure 1 displays annual changes in district K–12 enrollments from 2018–19 to 2023–24. Points on the negative side indicate an enrollment decline relative to the year prior; positives indicate an increase. The red line shows the statewide trend, while the thinner lines display trends by typology (rural, small town, suburban, and urban).

We first note the dip in enrollment during the pandemic-disrupted 2020–21 school year. But district enrollments have continued to slide, albeit not as steeply, in each of the following three years. According to the most recent data, statewide district enrollment fell another 1.2 percent between 2022–23 and 2023–24, a loss of 18,161 students. As for trends by typology, rural and urban districts suffered steeper losses during this five-year period, while suburban districts experienced smaller declines. For the current school year, small town and rural districts registered the largest declines relative to the year prior (-1.8 percent each).

Figure 1: Percentage change in district enrollment compared to the previous school year, by district type, 2018–19 to 2023–24

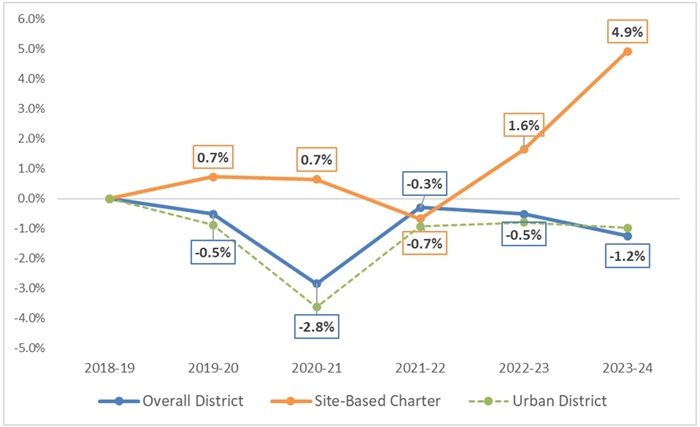

Adding public charter schools to the mix changes the picture dramatically. Figure 2 looks at the enrollment trend for Ohio’s site-based (a.k.a. “brick-and-mortar”) charter schools, thus excluding online charters. It shows that site-based charters not only avoided the enrollment drop that hit districts during 2020–21, but actually posted enrollment increases over the past two years. Between 2022–23 and 2023–24, site-based charter enrollments rose by an impressive 4.9 percent, a gain of 5,829 students. This annual increase easily topped districts overall (-1.2 percent) and that of districts in urban areas (-1.0 percent), which is where most site-based charters are located. Though not shown below, online charters have had even more robust growth during the time period. Their enrollments boomed in 2020–21 as families sought at-home instructional options, though they have somewhat fallen since then.[1]

Figure 2: Percentage change in enrollment compared to the previous school year, site-based charter schools versus districts, 2018–19 to 2023–24

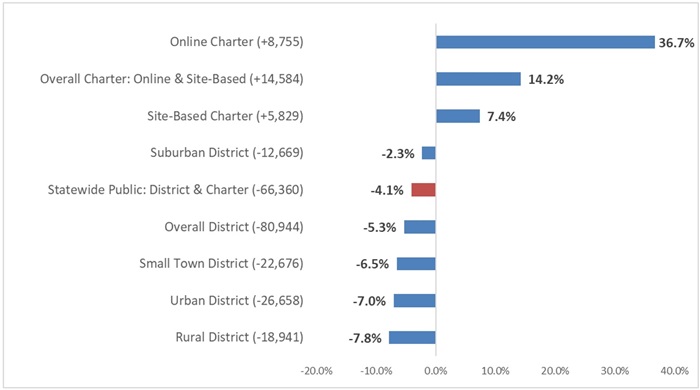

Figure 3 displays the cumulative changes in K–12 enrollment from 2018–19 to 2023–24. As the red bar indicates, total public school enrollment—district and charter combined—declined 4.1 percent during this period. District-only enrollment fell 5.3 percent, while site-based charter enrollment climbed 7.4 percent. To some extent, charters’ enrollment gains represent district losses, but it must be noted that district losses—almost 81,000 students—far exceed the gains of charters (+14,584 students). Thus, a large fraction of district enrollment losses can be attributed to other factors, such as students exiting for other educational options or declining school-aged populations.[2]

Figure 3: Public school (district and charter) enrollment changes, 2018–19 to 2023–24

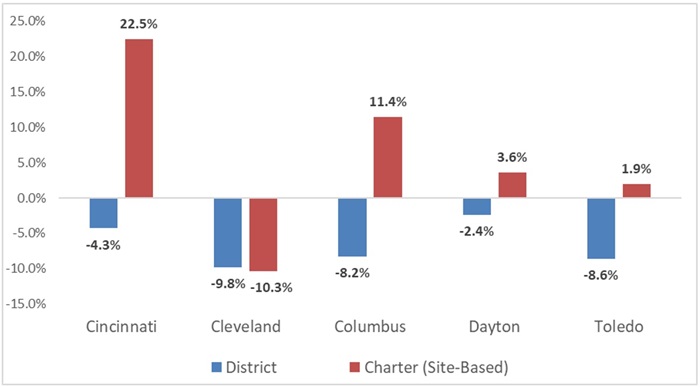

To close, we take a closer look at the trends in Ohio’s major cities where most site-based charter schools are located. Figure 4 shows some striking patterns. Of these locales, Cincinnati’s charter sector registered the largest enrollment increase (+22.5 percent), followed by Columbus (+11.4 percent). On the reverse side, Cleveland charters lost 10.3 percent of their enrollment during this period, a decline that is even steeper than the losses registered by the local district.

Figure 4: District and charter school enrollment changes in selected cities, 2018–19 to 2023–24

Though it has had a relatively small charter sector, Cincinnati’s impressive growth of late is partly attributable to the fall 2022 launch of the IDEA charter school, which has already scaled to serve nearly 1,000 students this year. This is great news for Cincinnati parents and students, as the school is affiliated with one of the nation’s top charter school networks. The other Cincinnati charter driving enrollment growth is Dohn Community, a dropout-recovery school that now serves more than 1,500 at-risk adolescents at multiple sites across the city.

Turning northward to Columbus, charter enrollment growth is led by KIPP Columbus, a perennial top-performer whose enrollment has increased by more than 600 students since 2018–19. The school now serves just over 2,000 students. (Fordham proudly sponsors both IDEA and KIPP Columbus.) Also notable are Cornerstone Academy and Columbus Bilingual Academy-North, whose enrollments are up by more than 200 students. With a new facility on the horizon (though just outside of the city), Cornerstone is poised for additional growth.

* * *

Enrollment trends often tell us something about the types of schools that families are gravitating to or moving away from. In the post-pandemic era, districts appear to be losing their edge, despite their historical position as a monopoly educational provider and their higher levels of taxpayer resources. Yes, they continue to educate a large majority of Ohio students. But persistent enrollment declines signal increasing parental interest in other options—particularly in light of recent legislative changes that have expanded access to private-school choice.

On the other hand, the state’s public charter schools are appealing to an increasing number of families. And the sector is also looking to meet those rising demands, as some longstanding schools are expanding their capacity and promising new startups are getting off the ground. With significantly improved funding starting this year, site-based charters are well-positioned for additional growth that can ensure more families seeking public school alternatives have quality options in their community.

Enrollments provide more than insights into parental demand, though. They also have implications for policy—an issue that I’ll cover in a follow-up piece. But for now, let’s cheer the work that charters are doing to serve an increasing number of Ohio families and students.

[1] Online charter enrollments grew by 46.1 percent in 2020–21 then fell by 5.9 and 1.6 percent in the following two years. Between 2022–23 and 2023–24, online charter enrollments increased by 3.4 percent.

[2] Private school enrollment increased by 6,484 students between 2018-19 and 2023-24. Homeschooling increased by 14,581 students between 2018-19 and 2022-23 (data are not yet available for this year). Note that private school competition, homeschooling, and demographic changes would also impact charter enrollments.

It’s been nearly a year since Governor DeWine delivered a state of the state address previewing his administration’s early literacy agenda. Since then, lawmakers passed the state budget bill containing the majority of DeWine’s recommendations, and giving Ohio a new policy framework for reading instruction.

The revamped framework centers on the science of reading, an instructional approach that research has proven is an effective way to teach children how to read. It focuses on five main components: phonics, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. It also rejects debunked instructional methods like balanced literacy and three-cueing.

Under the revised policy, public schools will be required to use curriculum, instructional materials, and intervention programs aligned with the science of reading. To ensure schools select high-quality options, lawmakers charged the Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) with creating a list of approved curricula.

On February 1, DEW released its initial list. It used reviews from EdReports, a national nonprofit dedicated to facilitating the adoption of high-quality instructional materials, as an “initial gateway measure” to help determine which programs would make the cut. Using EdReports reviews as a gateway measure makes sense for Ohio, because DEW worked alongside EdReports to develop Ohio Materials Matter, a state-specific resource that helps districts identify and adopt materials aligned to the state’s learning standards. EdReports reviews are also linked to the Ohio Curriculum Support Guide, a framework intended to help district and school leaders adopt high-quality materials. Both Ohio Materials Matter and the Ohio Curriculum Support Guide pre-date last year's budget changes. That means EdReports is already familiar to many Ohio schools, and that familiarity could help smooth the upcoming transition.

Public schools are required to begin using state-approved materials at some point during the 2024–25 school year. But it’s important to note that the recently published list of approved materials is not the final one. The final list will be published in March. Phase two of the state's review process is already underway, and additional materials may be added to the approved list in March as a result of this review. For some districts, it may be prudent to check out the final approved list before jettisoning their current curriculum. But for districts that already know they’ll need to make a change because they’re currently using a curriculum that’s not aligned with the science of reading, this initial list provides several options to consider if they want to get a jump on the transition.

So which vendors made the cut? The department identified three categories of approved instructional programs for grades K–5.[1] These programs share the same names as the three formats EdReports uses to review ELA materials. They are:

Core comprehensive programs, which include high-quality instructional materials that are comprehensive in scope and aligned to state standards. They reflect the reading research, and integrate the “aspects of language that underlie the process of learning to read.” Eleven programs made the cut. They include Amplify Core Knowledge (2022, K–5), Wit & Wisdom (2016, grades 3–5), and Wonders (2020 and 2023, grades K–5).

Core no foundational skills[2] programs, which include high-quality instructional materials designed to deliver instruction in most grade level content areas. They are aligned to state standards. However, they must be used in conjunction with a foundational skills program, as they don’t sufficiently cover foundational skills on their own. Two programs made the cut: Fishtank Plus (2021, grades K–2) and Wit & Wisdom (2016, grades K–2).

Foundational skills only programs, which include high-quality instructional materials aligned to state standards for foundational reading skills. These programs are meant to be used in conjunction with a core program, as they only deliver foundational skills content. Five programs made the cut, including Foundations A–Z (2023, grades K–2) and Savvas Essentials: Foundational Reading (2023, grades K–2).

Districts are permitted to use a combination of programs. For example, they could pair a supplemental foundational skills program with either a core comprehensive or a core no foundational skills program to cover all their bases. However, DEW notes that starting with a high-quality core program should be the goal, as it will likely “reduce the need to introduce multiple supplements or ‘patch together’ a set of materials that are not coherent and aligned.”

It’s heartening that curricula that rely on weak instructional methods—programs like Fountas & Pinnell and Units of Study—are absent from this initial list. Let’s hope that they are absent from the final list, too. It’s also important to remember that when it comes to curriculum, implementation matters. Obviously, an approved list of high-quality materials is a necessary foundation. But effective professional development around these materials in every school, as well in-depth training for future teachers, will be the true determining factor as to whether Ohio improves its reading achievement.

[1] Pre-kindergarten is also included on the list and has two options.

[2] The term “foundational skills” refers to foundational reading skills like phonics, fluency, and phonological awareness.

Public charter schools in Ohio have long struggled to secure adequate school facilities. Unlike traditional districts, charters are ineligible for the state’s generously funded school construction program, and they cannot levy local taxes for capital projects. Thus, while Ohioans often see news articles about gleaming new district-run schools, one would be hard-pressed to find more than a handful of ribbon-cutting stories for charters.

Because school construction is usually not financially feasible, charters sometimes look to purchase or lease a vacant district-owned building. Unfortunately, school districts have found ways to keep unused buildings out of the hands of charters—despite state laws that, on paper, give charters the right of first refusal. Back in 2010, Cincinnati Public Schools slapped a deed restriction on a vacant facility to avoid selling it to a charter school (the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that move illegal). And in 2020, Columbus City Schools refused to sell an unused building to one of the city’s top performing charter school networks in what appeared to be a direct violation of state law. District officials claimed they had plans for the facility and weren’t required to sell it. Interestingly, however, the building still sits vacant and in district possession.

In a more recent case, we discover yet another illustration of districts’ anti-charter bias, this time from Eastern Ohio. Salem City Schools is currently embarking on a school construction project that will allow it to consolidate elementary schools and thus vacate an existing building. Under state law, the district would need to offer the facility for purchase or lease to a charter school. But when asked if that might be a possibility, the superintendent was adamant that he’d find a workaround to ensure that the building doesn’t end up in the hands of the competition, either by repurposing it or even tearing it down. For some, the demolition tactic might sound familiar. More than a decade ago, Cleveland Metropolitan School District razed a building in an apparent effort to keep it away from charter schools.

Unfortunately, from a recent spate of news articles, it appears that school districts aren’t the only ones standing in the way of charters seeking facilities. Consider the following stories of local municipal officials blocking charters’ facility plans.

To be sure, school district and municipal officials have at times supported charter schools. In 2015, Cleveland agreed to lease one of its buildings to the Breakthrough network of charters. Two years later, Columbus City Schools sold two buildings to the Graham charter network. Meanwhile, the Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority has issued tax-exempt bonds on behalf of the Toledo School for the Arts to support the renovation and expansion of its facility.

But these stories seem to be more exception than rule. That’s disappointing, as Ohio charter schools are serving communities, parents, and students well. The most recent rigorous evaluation of the sector indicates that students attending brick-and-mortar charters outperform their district counterparts. The state’s best charter schools open doors for low-income students in their communities to attend college or pursue professional training. Instead of giving charters the runaround, local officials should be looking to support educational institutions that improve the lives of their citizens.

A new report suggests that too much time spent on enrichment activities outside of school is a harmful double whammy for young people, as it stalls cognitive skill growth and induces a decline in non-cognitive skills. Perhaps even worse, there appears to be very little positive benefit associated with even modest amounts of enrichment. While the analysts’ math checks out, parents and pundits alike will still have questions.

Data come from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), touted as the world’s longest running nationally representative panel survey, with almost fifty years of data on the same families and their descendants. University of Georgia researchers Carolina and Gregorio Caetano, along with Eric Nielsen of the Federal Reserve Board, focus on ten years of data from the PSID’s Child Development Supplement (CDS). Specifically, they zero in on the 1997, 2002, and 2007 waves of the CDS, which include time-diary data of students from pre-K through twelfth grade—reported by children or their parents, depending on age—as well as measures of cognitive and noncognitive skills. The robust data also allow the analysts to build controls related to child, family, and environmental characteristics.

The sample consists of 4,330 children ranging in age from five to eighteen years. We get no detail on how these children were specifically chosen. While the grade ranges of pre-K–5, 6–8, and 9–12 are roughly equally represented in the sample, with about one-third of the observations in each, other demographic details provided don’t seem particularly representative of the population at large. Approximately 40 percent of the children are Black, and 7 percent are Hispanic. Twenty-six percent attend a gifted program—far above the current 6 percent as reported by NAGC—8 percent attend a special education program, 1 percent are homeschooled, and 8 percent attend a private school.

Cognitive skills are measured by three assessments: the standardized letter-word, applied problems, and passage comprehension subtests of the Woodcock Johnson Revised Tests of Achievement, results of which are available for each CDS wave. Non-cognitive skills are measured in thirty-six different dimensions by parents’ answers to CDS survey questions and include things like “cheats or tells lies,” “argues too much,” “admired by other children,” and “does neat careful work.” Time diaries from CDS include full twenty-four-hour breakdowns of one random weekday and one random weekend day for each child. The original data coded activities into more than 300 categories. The present study aggregates these into eight: Class time, sleep, play and social activities, passive leisure, duties/chores, enrichment activities, broader enrichment activities, and a miscellaneous category for everything else.

The analysts define enrichment as “the kinds of activities that are typically considered to be investments in children’s skills” undertaken outside of school time. Their main enrichment category includes homework, reading for pleasure, before- and after-school programs, non-academic lessons (like cooking or violin), and other academic lessons (like tutoring or math camp). The “broader enrichment” category adds other familiar activities like structured team sports, art classes, museum excursions, and volunteering. While no two parents would likely break out these activities the same way, the analysts test their models with both enrichment categories and find similar results. They also perform robustness checks using different aggregations of the non-cognitive skills categories.

The model produces some attention-getting results. The full-sample analysis indicates that that enrichment time, when corrected for selection on unobservable factors that might influence the findings, has no significant effect on cognitive skills—the very goal for which the activities were undertaken—and a concurrent significant, negative effect on non-cognitive skills. These negative effects were visible and significant across all grade levels, but most pronounced at the high school level. On average, children in the sample spend about forty-five minutes per day on enrichment activities, but that adds up over a typical week, driving increasing the downward pressure on non-cognitive skills with each additional hour.

What’s going on with these counter-intuitive findings? The full answer is beyond the realm of this paper, but the analysts have some ideas. The simplest is that homework, the largest time use in the enrichment category (66 percent) and also tested by the analysts in isolation from all other activities in the category, doesn’t serve to increase cognitive skills as intended. One clear question here is whether the activities are perhaps disconnected from the cognitive skills tests given. Parents and pundits know that many enrichment activities are general in nature—aimed at developing well-rounded kiddos—but homework and tutoring are typically specific to classes and tests. Would the model show different results if actual class grades/GPAs/state test scores were used to indicate cognitive skills growth? Feels like a robustness check worth running! Less in question, though, seems to be the increase in negative aspects of measured non-cognitive skills. The more enrichment engaged in, the sadder, more irritable, and more inferior to peers the sample students felt. The higher homework load traditionally experienced by high schoolers would match the more pronounced effects seen at the 9–12 grade level.

Another suggestion is that it’s all a matter of time use substitution. Every time use in the enrichment category (but especially homework) is taking up hours that could be used for other activities—the analysts suggest socializing and sleeping—that research indicates are correlated with improved non-cognitive skills. Older children, with more demands on their time as they approach high school graduation, are apparently choosing to forgo these beneficial activities more than their younger brothers and sisters—which probably accords with parental experience outside the confines of a dataset—and are experiencing the negative effects more strongly.

It is unlikely that the authors were trying to antagonize parents working hard to do right by their children, but the results of this study are apt to dismay and alarm some parents. Questions may linger as to the sample and the methodology, but the main point stands: Finding the perfect balance of out-of-school activities to maximize cognitive and non-cognitive skill building for kids is not as simple as it seems. This research doesn’t give a solid answer as to what the balance should be, but the authors’ outcomes hint that it could be a different mix than many families have experienced.

SOURCE: Carolina Caetano, Gregorio Caetano, and Eric Nielsen, “Are children spending too much time on enrichment activities?” Economics of Education Review (January 2024).

Many states are overhauling their early literacy policies to align with the science of reading, an evidence-based approach that emphasizes phonics and knowledge building. Effectively implementing these reforms is crucial, as high-quality reading instruction can improve both academic and life outcomes for children.

The National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ), a leader of the effort to align state policy with reading science, argues that the best way to ensure strong implementation is by focusing on effective teachers. In a recently published report, it outlines five key policy actions that state leaders should take to strengthen elementary teachers’ ability to teach reading. These include setting specific and detailed standards for elementary teacher preparation programs, reviewing those programs to ensure they train prospective educators in the science of reading, adopting a strong elementary reading teacher licensure test, requiring districts to select a high-quality reading curriculum, and providing professional learning and ongoing support for in-service teachers.

As part of its analysis, NCTQ identified eighteen indicators across these five policy areas. Then, it evaluated the degree to which states (and DC) met those indicators. Based on the results, states fell into four performance categories: strong, moderate, weak, and unacceptable. Twelve states—Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Ohio, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Virginia—sufficiently address the indicators of all five policy actions, and thus earn a “strong” rating. Three others—Maine, Montana, and South Dakota—have weak reading laws and are given an “unacceptable” rating.

The report offers a detailed analysis of each policy action, including applicable research and a closer look at states that are doing particularly well (or poorly). Below are six of the big picture findings.

First, although nearly all states have standards for teacher preparation, only twenty-six have standards that address in detail all five core components of reading (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension). One in five states does not include in its standards strategies for addressing struggling readers, while twenty-one jurisdictions do not have standards for supporting English learners.

Second, most states lack specific review procedures designed to ensure that preparation programs are aligned with reading science. Fordham’s home state of Ohio earned kudos in this area, as it will soon audit preparation programs to ensure they’re training teacher candidates in reading science. Colorado and Indiana also earned mentions as states to emulate in this domain.

Third, only twenty states require a strong stand-alone reading test. Most others require a test that includes reading but is weak on the science of reading. Iowa is the only state without any licensure test that addresses reading.

Fourth, although research demonstrates that improving the quality of curriculum is a cost-effective way to boost student outcomes, only nine states require districts to select high-quality reading curricula. That means more than forty million students currently live in states that do not require districts to use high-quality reading materials.

Fifth, eighteen states make curriculum decisions transparent by publishing on state websites what each district uses or by requiring districts to publish the information themselves. Rhode Island is an exemplar in this realm, as it publishes a visualization tool that identifies which curriculum each school uses and whether the state considers it high-quality.

Lastly, thirty states require some type of professional learning on the science of reading for current teachers. Mississippi and Tennessee, in particular, offer excellent examples of professional learning and ongoing support via literacy coaches and district networks.

Overall, NCTQ finds that states are trending in the right direction regarding setting teacher preparation standards and providing professional learning opportunities. But many still have work to do with regard to embracing rigorous teacher preparation approval practices, requiring strong reading licensure tests, and ensuring that districts use high-quality curricula. For policymakers seeking to understand how their own state measures up against these model policies, the data profiles provided here are a great place to start. Some will have reason to cheer, while others may be spurred to action.

SOURCE: Shannon Holston, “Five Policy Actions to Strengthen Implementation of the Science of Reading,” NCTQ (January 2024).

As we approach September 2024, the education community is bracing for the expiration of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds. There’s a growing narrative that this marks a significant funding cut for schools. In places like Cleveland, this framing has been front and center.

Nobody likes to lose money. And if schools were facing steep budget cuts due to an unexpected loss of funding, this take would be understandable. But that’s not the case with pandemic relief dollars. ESSER funds have always been temporary. It’s right there in the name—these were emergency relief funds.

ESSER was the U.S. government’s swift response to the Covid-19 pandemic, a lifeline thrown to schools grappling with the herculean task of continuing education amid closures, remote learning challenges, and myriad health concerns. This funding was explicitly temporary, a bridge to help schools navigate the treacherous waters of a global pandemic and its immediate aftermath, not a permanent augmentation to their annual budgets. Schools were repeatedly and wisely advised to spend the dollars on non-recurring expenses to avoid creating financial cliffs when the funding inevitably expired.

And yet, it appears this advice went unheeded in many communities.

Analysts and advocates alike now argue that the cessation of ESSER funds will leave schools in the lurch, creating gaping holes in their budgets that they insist must be filled. For districts like Columbus City Schools, which used ESSER dollars for recurring expenses, including hiring more than 600 full-time staff–despite clear warnings to the contrary—this is undoubtedly the case. And unfortunately, taxpayers in these districts will likely be called upon to open their pocketbooks and fill the void. In some districts, like Cleveland, where philanthropic support previously being directed to projects identified by students has been repurposed to narrow the gap, the “solutions” will be even more disheartening.

It didn’t have to be this way. And if local leaders hadn’t purposely ignored the temporary nature of these funds, it wouldn’t have been. There is, quite frankly, no excuse for it. Choosing to direct relief funding toward permanent and recurring expenses is like using a one-time tax refund on a car down payment that you can’t afford only to be left scrambling when the regular monthly payments kick in.

And yet, it’s important not to forget that these funds served an important public purpose. First, ESSER dollars were a stabilization mechanism, helping to prevent catastrophic educational and operational disruptions during the pandemic. Second, they provided resources for innovation, enabling schools to experiment with remote learning technologies and hybrid educational models. Third, they empowered schools to adapt to an environment where health considerations had become just as critical as educational outcomes. And, finally, a portion were to be used to help students catch up academically.

From this perspective, it’s clear that ESSER funds have already achieved much of what they were intended to do. Schools have been stabilized. Innovations have been integrated into daily operations. Adaptations to the “new normal” of the post-pandemic world have already been made. Schools are arguably in a better position to face future challenges than they were pre-pandemic, thanks in large part to the temporary boost provided by ESSER. Of course, all is not rosy. Both nationally and in Ohio, despite some academic recovery, pandemic learning loss—especially for the most disadvantaged students—remains.

The upcoming expiration of ESSER funds signals a crucible moment. District and school leaders must assess which pandemic-era innovations—tutoring, additional social and emotional support, afterschool programming, etc.—are worth maintaining, and at what cost. It’s an opportunity to reevaluate budgets, prioritize spending, and ensure that the gains made during the pandemic are not lost, but rather integrated into a sustainable financial structure.

For their part, policymakers must independently determine which pandemic-era interventions most impacted student learning and whether there are promising ESSER-era expenditures that should become a regular part of state funding formulas. At the same time, state leaders should be prepared to address the budget cut framing that will inevitably occur this fall. The expiration of temporary federal funds is not a credible argument to malign state school funding investments—no matter how loudly some folks might say otherwise.

The end of ESSER funding should not be viewed as a crisis but as an expected return to a pre-pandemic state. It’s a moment to take stock, to learn from our experiences, and to move forward with a clearer understanding of what our schools need to thrive in a rapidly changing world. Let’s not be alarmist about the expiration of temporary funds. Instead, let’s focus on building a robust and sustainable education system for the future.