More evidence—this time from Ohio—that third grade retention works

Following Florida’s lead, about twenty states, including Ohio, have enacted laws that require schools to retain third gra

Following Florida’s lead, about twenty states, including Ohio, have enacted laws that require schools to retain third gra

Following Florida’s lead, about twenty states, including Ohio, have enacted laws that require schools to retain third graders who are struggling to read and provide intensive interventions that help them catch up. The basic idea is this: Students with serious reading deficiencies need more time and support to develop the literacy skills required for middle and high school–level work. But without a statewide requirement, there is no guarantee that schools will step in at this critical juncture and offer extra help. Instead, they’ll likely default to “social promotion,” a practice that passes students along even though they are poor readers.

Despite the commonsense nature of this approach, third grade retention policies have been hotly debated in Ohio. Critics often claim that retention harms students who have to repeat third grade. But the evidence to support this claim is thin—and growing flimsier by the day. In fact, we now have four rigorous analyses of states’ retention provisions that say exactly the opposite: Struggling students benefit when schools are required to retain and provide them with more support before promotion to fourth grade.

Let’s first recap the studies from three other states with third grade retention policies similar to Ohio. All of these analyses rely on a rigorous empirical method that allows for apples-to-apples comparisons of retained versus extremely similar non-retained pupils who just narrowly pass the promotional bar. This method provides strong causal evidence on the effect of retention (as opposed to social promotion).

What about Ohio? A new study, commissioned by Ohio Excels and conducted by professors at the Ohio Education Research Center at Ohio State, finds strikingly similar results. Starting in 2013–14, about 3 to 4 percent of Ohio third graders have been retained under the Third Grade Reading Guarantee.[1] Following the same methodology as the studies above, the Ohio analysis focuses on the first two cohorts of third graders who were subject to the guarantee policy and tracks their state exam results through seventh grade.

The positive effects of retention are substantial for students who repeated third grade. In fourth and fifth grade, retained students outperform their closely matched peers by approximately twenty to forty scaled-score points—equivalent to roughly one achievement level—on state math and reading exams. The academic gains for retained students persist and remain significant into sixth and seventh grade, though the size of the impact moderates to a ten- to twenty-point advantage. Much as good elementary schools are needed to fully capitalize on preschool, this suggests that some extra support remains important as retained pupils progress through higher grades. Overall, these results show that retention provides a big lift for thousands of Ohio’s struggling readers and helps put them on surer pathways in middle and high school.

Because literacy is so essential to lifelong success, elementary schools have no greater responsibility than ensuring that children can read fluently. Fortunately, state leaders have understood this. Former Governor Kasich recognized the importance of reading by grade three when he signed the Guarantee, saying, “Kids who make their way through social promotion beyond the third grade, when they get up to the eighth, ninth, tenth grade...they get lapped, the material becomes too difficult.” Last week, former U.S. congressman and president of the Ohio Business Roundtable Pat Tiberi said, “There's no more significant benchmark in education than ensuring that students are proficient readers before they leave elementary school.” Earlier this year, Governor Mike DeWine called fully educating students a “moral imperative” and noted that “the earlier a child is reading on grade level, the better that child will do in later grades—and in life.”

Ensuring children can read is indeed a moral imperative. There’s wisdom in giving struggling readers more time and support to strengthen their literacy skills, and research confirms it. It would be reckless for lawmakers to backtrack on retention, as some have proposed, especially as Ohio seeks to get even more serious about early literacy through its praiseworthy science of reading initiatives. Instead, they should stay the course on retention and make certain—truly “guarantee”—that all children read well before they enter fourth grade.

[1] The retention policy was suspended in 2019–20, 2020–21, and 2021–22. It is in effect this school year (2022–23).

A few weeks ago, researchers from the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University and Stanford University’s Educational Opportunity Project published an Education Recovery Scorecard that offered an in-depth and dire look at the pandemic’s impact on student achievement.

In an analysis of their findings written for The New York Times entitled “Parents don’t understand how far behind their kids are in school,” lead researchers Tom Kane and Sean Reardon write that although most parents think their children have either caught up from the pandemic or will soon do so, the “latest evidence suggests otherwise.” In fact, according to their research, by the spring of 2022, the average student was half a year behind in math and a third of a year behind in reading. Furthermore, their findings suggest that “within any school district, test scores declined by similar amounts in all groups of students—rich and poor, White, Black, and Hispanic.” In short, learning loss is widespread and significant, it’s impacting all kids, and schools have a ton of work to do to catch them up. (Kane reiterated these points when he recently appeared on the Fordham Institute’s Education Gadfly Show podcast.)

In their Times piece, Kane and Reardon recommend that in districts where students lost more than a year’s worth of learning, state leaders should require districts to “resubmit their plans for spending the federal money and work with them and community leaders to add instructional time.” That’s especially good advice for Ohio, as schools in the Buckeye State haven’t been particularly forthcoming about how they’re spending federal money to address learning loss.

Over the course of the pandemic, Ohio received more than $6 billion in federal relief aid to help schools. Ninety percent of the funding was distributed directly to schools. But neither the state nor the feds tied these funds to stringent transparency requirements or measures. As a result, state leaders and the general public have no idea how billions of dollars have been spent, or whether it has succeeded in helping kids. The State Board of Education has discussed district expenditures at a few of their meetings. There are some news stories about initiatives and improvements that are being paid for. Some districts have vaguely outlined on their websites how they are using or plan to use the funds, and the state has spotlighted others. But for the most part, nobody knows anything.

The state’s effort to establish a robust high-dosage tutoring program is a prime example. Last year, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) launched the Statewide Mathematics and Literacy Tutoring Grant, a program paid for by federal Covid relief funds and aimed at developing and expanding tutoring for K–12 students in the wake of pandemic-caused learning loss. The program specifically focuses on high-dosage tutoring (HDT), which research shows can produce large learning gains for students.

The state announced it would distribute up to $20 million to both public and private two- and four-year colleges and universities with teacher preparation programs, and that they would be responsible for overseeing the tutoring efforts. In a previous post, I explained why involving higher education institutions in this manner was a good idea. First, it addressed one of the biggest barriers to establishing an effective, statewide tutoring program: finding enough tutors. Second, it allowed teacher candidates who serve as tutors to gain hands-on instructional experience and training. A definite win-win.

And yet, despite the win-win nature, schools have largely kept their HDT programs to themselves. One would think, given the troubling size and scope of learning loss across the state, that they’d be shouting from the rooftops about how they’re collaborating with local higher education institutions to offer students learning recovery opportunities. They should be telling anyone who will listen that they’re regularly offering kids the support and intervention they need to catch up as proof that they’re doing everything they can. But they’re not.

The state’s website identifies every grantee, so we know which institutions of higher education were awarded funding, how much they received, and which K–12 districts and schools they’re partnering with. But in most cases, that seems to be all we know. For example, twenty-six grantees were awarded funding to run tutoring programs for both math and literacy. But broad web searches, as well as searches of the websites belonging to the K–12 districts and schools that grantees are working with, turn up very little information about the details of these programs.

There are some exceptions. In October, the Plain Dealer published a piece about how officials at Fairview Park City Schools reached out to staff at Baldwin Wallace University in northeast Ohio about starting a tutoring program. The state awarded the university nearly $300,000 to make it happen, and Baldwin Wallace education majors are now offering intensive tutoring in math and reading to students at a Fairview Park elementary school three times a week. Bowling Green State University was awarded $700,000 and is now running an after-school program that matches pre-service teachers with students who need additional help. Tutors and students meet twice a week, both in-person and remotely. Heidelberg University is also using its nearly $300,000 grant to run an afterschool program, and it’s doing so for a small number of students from a wide range of schools—including a traditional public school, a charter school, and a private school.

However, most of the publicly available information that exists about these efforts has been provided by higher education institutions, and not districts and schools. It’s worrisome that K–12 schools aren’t doing more to communicate to parents and the public that they’ve partnered with local universities to offer HDT to struggling students. Obviously, a lack of online information doesn’t mean that districts and schools haven’t communicated with families at all. But easily accessible information on school websites is often indicative of how transparent schools are with their communities about what matters—and how committed they are to addressing problems.

The bottom line is that Ohio’s attempt to get a statewide HDT initiative off the ground reflects a larger problem with the under-the-radar way the state’s schools are handling learning loss. Thanks to state report cards, national assessments, and the vital work of researchers like Kane and Reardon, those of us who are immersed in education policy know that learning losses are persisting. We know that the educational reality for tens of thousands of kids is stark and sobering and must urgently be addressed. But most parents and community members don’t realize how big the problem is, and they’re unaware of how their local schools are (or aren’t) addressing these academic challenges.

We have to do better. If hugely promising interventions like HDT aren’t headlining schools’ communication efforts—or even getting mentioned on their websites—then we have to ask whether schools are doing everything in their power to get children back on track.

By now, it’s no secret that the pandemic and schools’ pivot to remote learning was a disaster for most students. Various studies have documented severe learning losses based on both national and state assessment data. The federal government sent an unprecedented $200 billion to U.S. schools to help students get back on track, and schools are supposed to be spending these dollars on remediation efforts. Yet students are still far from caught up, and a recent analysis led by a team of Harvard and Stanford researchers is another clarion call for strong academic recovery.

Known as the Education Recovery Scorecard, this ambitious project relies on pre- and post-pandemic data from 2018–19 and 2021–22 to gauge changes in math and reading performance in districts across the nation. The Scorecard adds important new perspective on the academic declines, both nationally and right here in Ohio.

First, the analysts estimate how many grade levels behind current students are compared to their pre-pandemic peers. This way of reporting learning loss may be more intuitive for the general public, and offers a clearer sense of the work needed to help students recover lost ground. Tom Kane, one of the lead researchers, notes, “The hardest hit communities…where students fell behind by more than 1.5 years in math would have to teach 150 percent of a typical year’s worth of material for three years in a row—just to catch up.”

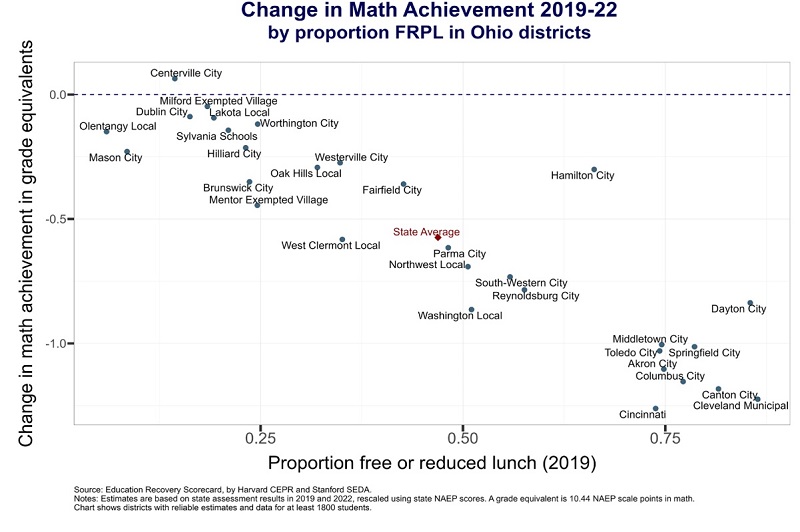

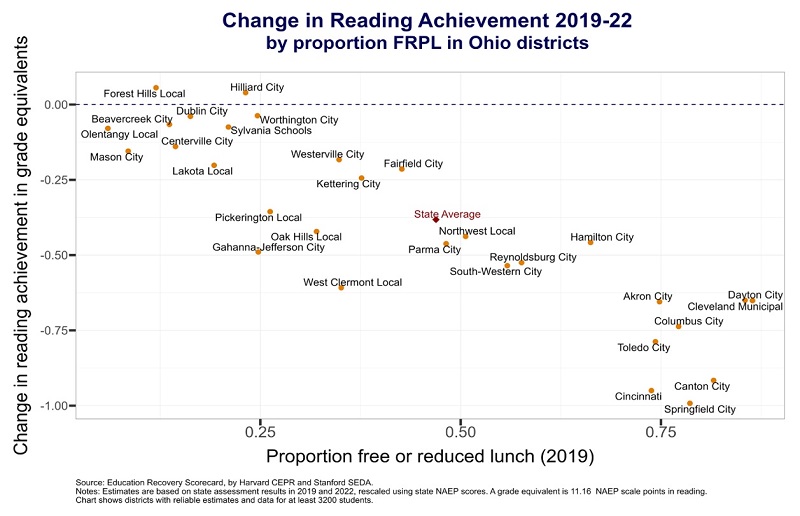

Put this way, the academic catastrophe in Ohio’s high-poverty, urban districts comes into even clearer light. Consider the charts below, the first of which displays the learning losses of selected Ohio districts in math. We, first of all, see a correlation between districts’ learning losses and student poverty rates. At the top left corner are several affluent districts that came away relatively unscathed by the pandemic. Towards the middle of the chart, we find the statewide average loss of just over a half grade level in math, along with some mid-poverty districts.

But at the bottom right corner are districts such as Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus, where students are more than a grade level behind their pre-pandemic counterparts. Using Kane’s rule of thumb, Columbus students, for example, need about a year and half of instruction—for two years—to catch up to their pre-pandemic peers attending the district. Keep in mind that Columbus students were already lagging well behind state and national averages prior to the pandemic. In 2019, the typical Columbus student was 2.5 grade levels behind the national average. In 2022, she was a staggering 3.6 grade levels behind.

Results follow a similar pattern in reading, though the declines in this subject are not quite as steep as in math. The average student in Ohio is about two-fifths of a grade level behind their pre-pandemic peers; in high-poverty urban districts, they are between a three-fifths and a full grade level behind.

The Scorecard also allows for cross-state comparisons of learning loss. One can gauge how students in Cleveland or Columbus fared during the pandemic compared to their counterparts in Detroit, Indianapolis, or Pittsburgh. This unparalleled picture of learning loss across state lines is made possible through statistical methods that crosswalk districts’ state exam scores with state-level results from the 2019 and 2022 rounds of the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

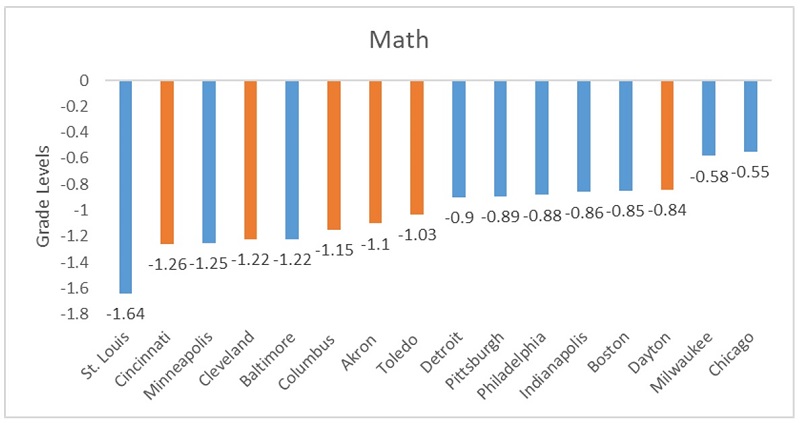

Sobering results emerge when comparing Ohio’s big-city results to other urban districts in the Northeast and Midwest. The top figure shows that the learning losses in Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Akron, and Toledo exceeded those of many other cities—and were roughly double the losses in Milwaukee and Chicago. Of the large urban districts in Ohio, Dayton suffered the smallest declines in math.

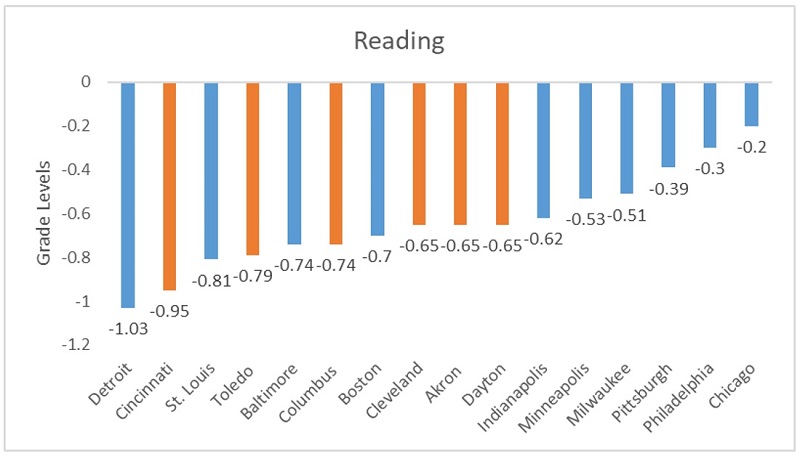

The results are broadly similar in reading, with Ohio’s large urbans faring somewhat poorly compared to other districts in the nation. Why some urban districts weathered the storm better than others is a tough question to answer definitively. It’s likely related to how long schools were closed, what types of supplemental opportunities they’ve offered students, how the pandemic affected their teaching workforce, and other variables. A recent study by analysts engaged in the Scorecard sought to identify the most significant factors, but found that “no individual predictor [of learning loss] provided strong explanatory power.”

* * *

Kane and Sean Reardon, the other lead researcher for the Scorecard project, offer a number of solid ideas in a New York Times editorial about how to help students catch up. Among them include summer programs, awareness efforts, and tutoring. Consistent with those suggestions, I wish to highlight three specific steps that Ohio schools—especially those in urban areas—can immediately take to support students who have fallen behind.

1. Make good use of this summer. Schools should strongly encourage, or even require, students who score at the lowest level (“limited”) on this spring’s state assessment to participate in summer learning programs. Extra learning time above and beyond the typical school year is absolutely critical to helping students get caught up.

2. Send state exam results to parents ASAP. Recent survey data from Learning Heroes indicates that nine in ten parents believe their child is on grade level, likely reflecting the rosy grades that come home via report cards (four in five parents say that their children receive mostly A’s and B’s). This misinformation can do real harm to students, as they miss out on the extra supports their parents would otherwise secure if they knew the truth. State exams often provide a more realistic picture of academic proficiency, and schools need to make sure that parents receive these results right away so they can act swiftly on behalf of their children.

3. Inform parents about the ACE account program. In 2021, Ohio created a new program known as the Afterschool Child Enrichment (ACE) account. It currently provides low- and middle-income parents $1,000 per child that they can use to cover the costs of learning opportunities, such as afterschool tutoring, day camps, and music and art lessons. Schools should be informing parents of this program and proactively encouraging them to apply for the funds. Much like summer school, students stand to benefit when they have extra time and learning supports.

The pandemic has thankfully receded and isn’t at the top of our collective consciousness anymore. But its effects are still being felt, most of all by our youngest citizens. To do right by students who have fallen off track, state and local leaders need to do everything in their power to support a strong recovery.

One of the more variable aspects of charter school operation around the country is the system by which schools are authorized and managed. Some states limit the number and type of authorizers and management structures; others open the door wider, allowing different types of entities to authorize and to run charter schools. Each approach has pros and cons, but evidence on the outcomes associated with various models is thin. A new report examines Indiana, a state with an expansive structure allowing multiple authorizer and operator types, to see how the interconnected parts impact student academic outcomes.

A research team led by Joe Ferrare of the University of Washington, Bothell, chose the Hoosier State because of its long history of charter schools, with multiple authorizer and operator types, and because of its similarity to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools’ “model law.” On the authorizer side, Indiana allows institutions of higher education, a state charter school board, and the Indianapolis mayor’s office (a type unique to Indiana) to authorize charters. In terms of operators, the state allows charter management organizations (CMOs), which are nonprofit entities that manage two or more charter schools; educational management organizations (EMOs), which are for-profit entities that manage charters by contracting with operators and perform similar functions as CMOs; and independent operators, who perform all management functions themselves. The researchers were looking to see if students fared better or worse in schools with different authorizer and operator combinations.

Student-level data come from the Indiana Department of Education and cover all public school students in grades three through eight in the school years between 2008 and 2018, including their performance on state math and ELA tests given annually. Ferrarre and his team identified an initial group of students who switched from any traditional district school to any charter school (virtual and brick-and-mortar) during the study period, as long as students moved in grades three through seven and had spent at least one year in their district school before switching. Each switcher was then matched with at least one peer—sharing gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic level (as determined by free or reduced-price lunch status), and math and English language arts baseline test scores—who remained in his or her district school. School switchers were matched with as many non-switchers as fit the criteria, thus the treatment group ultimately included 11,284 students attending eighty-eight charter schools across Indiana, compared to 46,060 control group students attending 1,343 traditional district schools. This represents 61 percent of the initially-identified switchers, nearly 20 percent of all Indiana charter students in grades three to eight, and 93 percent of all charter schools. Students and their matched peers were followed for a maximum of three years. Importantly, there was no minimum amount of time required of switchers to stay in their charter schools: initial school switchers were treated as permanent switchers even if they moved back to a traditional district school (or made a combination of moves) at any point following the initial switch. More on this below.

Critical to the analytical intent was the distribution of treatment students across authorizers and operator type. Higher education entities—comprising Ball State University, Grace College, and Trine University/Education One—represented forty-six schools and 8,617 students; the Indianapolis Mayor’s Office represented thirty-two schools and 2,460 students; and the Indiana State Charter Board represented ten schools and 207 students. As to operator types: Charter Management Organizations (CMOs) represented forty-one schools and 3,349 students, independent operators represented thirty-four schools and 2,908 students, and Education Management Organizations (EMOs) represented six virtual schools (4,343 students) and seven brick-and-mortar schools (594 students).

So how did students switching into charters fare on their math and ELA tests based on the authorizer type? On average, switchers in schools authorized by Ball State experienced large, negative effects in math that persisted across time and moderate losses in ELA that were not statistically significant after three years. Trine/Education One charter students saw large losses in math for the first two years, but recovered by year three, and saw large losses in ELA for the first year only. Grace College charter students experienced a similar pattern of losses to Trine, but smaller in magnitude. By contrast to the higher education-based authorizers, overall estimates for students switching into charter schools authorized by the state returned null effects across the board, while students switching into charters authorized by the Indianapolis mayor’s office saw moderate but significant increases in both math and ELA scores.

But does this mean that higher education entities are the worst-performing authorizers overall? That depends. When looking at outcomes by operator type, schools run by CMOs had small positive effects in math and ELA over all three post-treatment years. Independently-operated charters showed small but significant negative effects in math across all three years, and null effects on ELA. Brick-and-mortar schools run by EMOs showed positive effects in ELA across all three years, null math effects for years one and two, and positive effects on math scores in year three following a student’s switch. Virtual schools run by EMOs showed almost entirely large and negative effects, except for a null impact on math scores in the third year post switch.

Combining these two sets of results yields a sizeable matrix of outcomes showing that the impacts of authorizer type and operator type interact. All of the various permutations are worth a read, but just for one example: The researchers find that the negative effects of Ball State’s charters were driven by their EMO-operated virtual schools, whose students showed significant declines on test scores in both ELA and math across all years. Negative impacts were also seen across all years and subjects in Ball State’s independently-operated charters, although far lower than in the EMO-virtual schools. Meanwhile, their EMO-operated brick-and-mortar schools actually produced positive and significant effects in both subjects in all but one year under study, completely opposite of the findings if authorizer type is the only variable.

In short: High-quality authorizers and high-quality operators are required to provide the best academic outcomes for students.

Ferrare and his team executed numerous robustness checks to help eliminate concerns about the internal and external validity of their model and seem satisfied. However, some additional nuance is likely required due to the fact that the model treats all initial school switchers as permanent switchers even if they moved back to a traditional district school (or made a combination of moves) at any point following their initial switch. More differentiation between groups is likely required to fully explore the impact of school structure on single vs. multiple switchers.

While the overall finding is that authorizer and operator type matter greatly in producing positive student outcomes, the interactions between the two layers are clearly complex. Generalizability to other states is probably limited as well based on several characteristics unique to Indiana. However, the researchers’ recommendations here seem relevant to other contexts: Making authorizers focus on improving or closing persistently low-performing schools (at the risk of losing their ability to authorize if they don’t), changing fee structures to incentivize academic achievement, and increasing transparency around corrective action efforts. Much of this already exists in Indiana law, but with plenty of wiggle room. Perhaps Hoosiers should take a page from the Buckeye playbook in the realm of charter law improvements.

SOURCE: Joseph J. Ferrare, R. Joseph Waddington, Brian R. Fitzpatrick, and Mark Berends, “Insufficient Accountability? Heterogeneous Effects of Charter Schools Across Authorizing Agencies,” American Educational Research Journal (May 2023).

Quantifying learning loss experienced by students whose schools closed for extended periods during the coronavirus pandemic is vital. Figuring out the mechanisms by which the losses happened, in contrast, is more of a forensic exercise. Schools have generally been open for more than a full school year now. At least two classes of seniors have graduated, many of their peers seem to have given up, and those remaining are experiencing whatever version of remediation is available to them. Whatever happened is already done, and time has marched relentlessly on. Nevertheless, setting the record straight on the means by which school closures impacted student learning must be part of our reckoning with the pandemic responses chosen and our planning for the future.

Harry Patrinos, an education economist and adviser with the World Bank, offers us a new working paper that extends an ongoing series of World Bank Group research attempting to identify the mechanisms of learning loss for primary and secondary school students all around the world. He specifies that this publication is a “work in progress,” but its findings form part of the full, grim picture we will eventually have.

Data come from numerous studies of pandemic-era impacts in more than four dozen countries. Many findings were already published earlier this year, and the new work adds additional countries and data. Patrinos looks at eleven factors potentially increasing or mitigating learning loss, which is defined using test score data via country-specific instruments that were standardized for comparison. Some of the factors are obvious—pre-existing school quality, school closure duration, private school enrollment, and internet availability and access—while others such as trade union strength and “measure of democracy” seem somewhat tangential. Control data include Covid-19 death rates per 100,000 population, a lockdown stringency index, vaccination rates, and national income. The working paper notes that not all available data are nationally representative. While learning loss in the United States is representative of all students, school closure duration varied state to state and is reported as a national average. Nepal’s data, as another example, come from a study that only includes adolescent girls from one disadvantaged district, but is compared directly to countries with much more robust datasets.

First and foremost: There is a clear link between school closure duration and learning loss. Closures as part of government-imposed lockdowns averaged twenty-one weeks’ duration and resulted in an average learning loss of 0.23 standard deviations across the countries studied (representing two-thirds of the world’s population). Testing for mitigating factors or other means to explain learning loss produced no significant findings, meaning that school closures appear to be directly responsible for student learning loss.

Patrinos notes that the American Academy of Pediatrics released the first school guidance for safe in-person learning in the United States on June 24, 2020, and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control released its recommendation on August 6. “By the time of the 2020–21 school year,” he writes, “it had become clear that it was possible to safely open schools.” However, many schools around the world remained closed for many more months. Sometimes that was due to longer (or recurrent) lockdown requirements, but data show that other factors were associated with non-mandated closures. Higher-income countries had shorter durations of school closures, while a low vaccination rate was associated with longer school closures. Higher test scores before Covid-19 were associated with longer school closures—perhaps an indication, Patrinos suggests, of hope for resilience of students or a belief in whatever remote learning was in place—as was a higher proportion of private schools in a country. Interestingly, the death rate does not correlate with school closure, suggesting that closure decisions were based on many factors other than actual Covid fatalities.

Whatever the reason for extended closures, Patrinos finds that each additional week of school closure increased learning loss by a further 1 percent of a standard deviation. In short: The longer schools stayed closed, the less students learned, no matter what else was done to blunt the losses.

Despite the huge trove of data we now have available, more will come. Researchers will continue to enlarge and sharpen the picture, but it seems pretty clear already. “The main lesson learned,” Patrinos concludes, is that “if a similar situation arises, keeping schools open should be a priority, as the evidence shows that the health benefits of school closures seemed to have been lower than the cost of learning losses.” Sobering thoughts for some unwanted “next time,” hollow validation for everyone who believed that reopening schools quickly was the best move, and a steep climb ahead for those trying to undo the damage already wrought.

SOURCE: Harry Anthony Patrinos, “The Longer Students Were Out of School, the Less They Learned,” World Bank Group Working Paper (April 2023).

NOTE: This piece was originally published by RealClear Education.

According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the majority of Ohio’s fourth-graders are failing as readers. And only two out of eight Ohio children living in poverty are proficient in reading. This is a wake-up call that demands attention: early-grade reading proficiency correlates directly with future earnings, college attendance, homeownership, and retirement savings.

Equally troubling is that, over the past two decades, NAEP scores have remained mostly flat – that is, until recent declines, which have mirrored national trends driven largely by the pandemic. By all standards, then, Ohio is failing its children.

We can address this crisis before it is too late: Governor Mike DeWine is seeking major funding from the legislature to retrain teachers, update textbooks, and support the science of reading as the exclusive approach to reading instruction. This focused investment is the kind of intervention that is needed to put kids – and the state – back onto the path of economic vitality.

One of our greatest challenges is the unevenness of classroom instruction. This is often caused by inconsistent teaching methods and training; state law allows districts to teach reading however they wish, and it gives teacher-education institutions much latitude in training future teachers in reading instruction. Indeed, as the National Council on Teacher Quality just announced, some higher-education institutions are failing to provide appropriate and effective preparation as well.

By reshaping policy around evidence-based approaches in classrooms and educator-training programs, we can provide children across the state with quality instruction based on the science of reading. Statewide implementation will help improve metrics and bring a consistent approach that has proven results.

The science of reading is an empirically based approach to reading and writing, developed over five decades from thousands of studies conducted in multiple languages. It works.

While some teachers still want to use other instructional methods (such as “cueing”), the reality is that if those methods were effective, the results would demonstrate as much. They do not.

Ohio can do better. By using evidence-based decision-making and adopting best practices, we can give students the best chance to thrive – as some states are already doing.

After investing heavily in the science of reading, Mississippi demonstrated more growth in reading scores than any other state. Mississippi became one of the few states that saw reading scores bounce back after prolonged school closures. In less than a decade, the state jumped from 49th to 22nd in the nation in reading proficiency. Mississippi made good on a promise to do better for its children. When this same method was tested in a rural Ohio school system, it resulted in double-digit improvements.

The rest of Ohio needs this chance to succeed, too.

StriveTogether believes that key inflection points in life determine future opportunities, including early-grade reading and middle-grade math. Ohio’s children need to be prepared for the next generation of jobs. With tech companies like Intel, Facebook, and Amazon having offices here, Ohio could become a tech hub. But Ohioans will fill those jobs only if they possess the needed skill sets to perform them – and all learning in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and technology) requires a solid foundation in reading.

Governor DeWine’s proposal enjoys bipartisan support and is championed by practicing administrators as well as community-based organizations like Learn to Earn Dayton, which consistently delivers positive outcomes for Ohio children.

Ohio needs to follow the research and do better for the kids of our state – and that means aligning efforts around the science of reading.

Thomas J. Lasley, II is Director of Policy and Advocacy, Learn to Earn Dayton and the Montgomery County Educational Service Center. Jennifer Blatz is President and CEO of StriveTogether.

NOTE: This piece was originally published in the Dayton Daily News.

I recently visited seven U.S. presidential libraries. I couldn’t help but notice in the recounting of their administrations that each of the presidents fervently believed that education was the most promising path out of poverty. Each made education a priority.

Dwight Eisenhower advocated for the National Defense Education Act after the Russian launch of Sputnik in 1957. Lyndon Johnson crusaded for a War on Poverty, making quality education for all children a central plank. George W. Bush successfully persuaded Congress to pass the No Child Left Behind Act.

Sadly, all of these efforts failed to meet the presidents’ boldest goal of making the United States a world leader in education.

Recently, states have tried to improve young children’s reading skills by establishing Third Grade Reading Guarantees. The focus on reading is premised on the belief that if children can’t read well, then every subject, in every grade, will be difficult to master.

In 2013, Ohio passed its own “guarantee.” The objective was right. But there were too many exceptions and loopholes. As time has shown, despite the best of intentions, the “guarantee” has failed to move the reading proficiency needle. In 2022, more than a third of Ohio’s third-graders were not proficient readers.

Why is that good idea failing? I’d argue that we have inconsistently and poorly implemented the policy. More specifically, we continue to misunderstand and confuse “standards” and “curriculum.” Academic standards are what every child should know and be able to do at each particular grade level. The curriculum, on the other hand, is how standards are taught, with the goal of every child successfully meeting standards.

The Third Grade Reading Guarantee set an important standard, but lawmakers failed to take the next step and insist that schools use an evidence-based curriculum to teach reading. Instead, they left it up to each school district to pick its own approach to the reading curriculum. Too many have chosen poorly—specifically neglecting key reading pillars such as phonemic awareness.

Unfortunately, that local control approach has not worked. It’s time to be prescriptive—especially when it comes to something as fundamental to student success as reading.

Gov. Mike DeWine has proposed requiring that teachers use an approved curriculum based on the science of reading. The mandated curricula and instructional materials will be chosen based on best evidence-based practices and what has worked successfully in other states across the country.

Additionally, colleges and universities would be required to prepare teachers to teach reading using proven pillars of effective reading instruction such as phonics, phonemic awareness and vocabulary.

Some levels of the education establishment undoubtedly will find ways to object, including teacher associations and colleges and universities. They’ll argue the governor and supporters are going overboard, and, as professionals, they know better what works.

We have tried to make a national difference for several decades in student achievement, which depends on students knowing how to read. But test scores have, at best stagnated.

It’s time to make a wholesale change. It’s time to get serious and require students be taught using instructional methods we know work. We must make the change at every level of our education system, from higher education to every school district and classroom.

The governor needs our support. Only if school districts are required to use evidence-based instructional approaches with fidelity will we ensure all children are strong readers.

Tom Gunlock is the Chair of the Wright State University Board of Trustees and a former member of the Miami University Board of Trustees and the State Board of Education.