Introduction and Summary

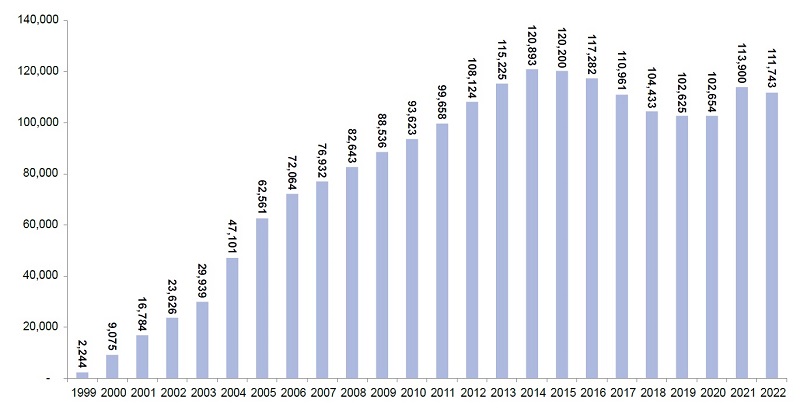

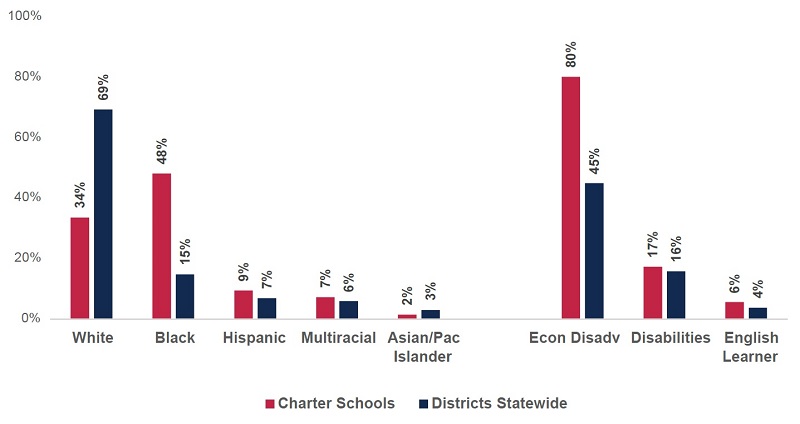

Since their inception in 1998, public charter schools have become an integral part of Ohio’s K–12 education system. The sector began with just a few schools educating a sliver of the state’s students, but has since grown to 324 charter schools in 2021–22, serving some 110,000 students, or 7 percent of the state’s public school population. Most charter students in Ohio are economically disadvantaged (80 percent) and/or Black or Hispanic (57 percent). Roughly three quarters enroll in brick-and-mortar schools, while the rest attend online charter schools. In cities such as Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown, more than one in four public school students attend charter schools.

At the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, we have long supported the promise of charter schools. Foremost, students who are ill-served by traditional school systems deserve other education options that can help unlock their potential. Entrepreneurial educators also need room—outside the clutches of district bureaucracies and union contracts—to create schools that offer specialized instruction and innovative models. Parents from all communities deserve a wider menu of public-school alternatives from which they can select that will best serve their children.

Around the nation, states have harnessed the charter school model to empower parents and educators and drive higher student achievement. Ohio embraced this model, as its charter sector took off with enrollments growing unabated from 2000 to 2015. Yet, too many Buckeye charters struggled—alongside many of their district counterparts—with educational performance during this period. Some also ran into management and fiscal troubles. Worrying news stories surfaced about questionable practices, and the quality challenges came to a head in the mid-2010s, with a firestorm over the then-huge, but now-defunct, online charter known as ECOT.

Responding to concerns raised by Fordham and others, state legislators wisely overhauled Ohio’s charter law in 2015. The legislation, House Bill 2 (HB 2), toughened charter accountability measures and demanded more responsible practices from those working in the sector. The bill included dozens of reforms, but its centerpiece was stronger accountability for charter sponsors—the entities that permit charters to open, directly oversee them, and, if necessary, require them to close. The first part of this report documents the clean-up that took place in the wake of those accountability reforms. Key changes included:

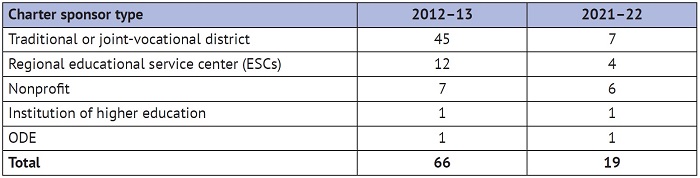

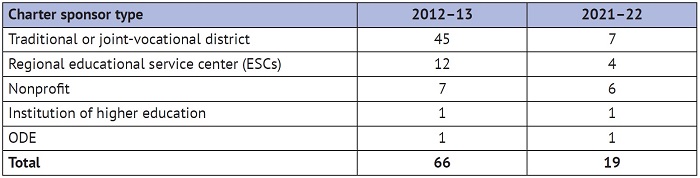

- The exit of dozens of low-capacity sponsors. Just prior to the HB 2 reforms, Ohio had a whopping sixty-six sponsors overseeing charters, most of which had no business authorizing schools. Thanks to stronger accountability from the state, low-capacity sponsors have left the authorizing business, and only nineteen remain in operation today. The Institute’s sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, has served as a sponsor since 2005 and it presently authorizes thirteen charter schools.

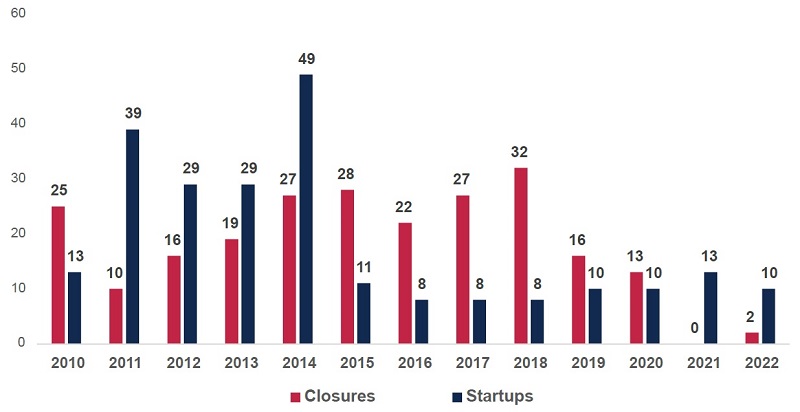

- Permanent closure of more than one hundred low-performing schools. Facing stricter accountability, remaining sponsors got serious about holding the charters they authorize to higher standards and have aggressively moved to close low-performing schools. (HB 1’s anti-“sponsor hopping” provision helped ensure these decisions were final.) Between 2015–16 and 2021–22, 112 charters—roughly one quarter of the sector at its peak—closed their doors. In many cases, these closures were the direct result of sponsor actions; in others, schools chose to close voluntarily as they were no longer viable, due to low enrollment. In just one case was a school shut down due to the state’s automatic charter closure law.

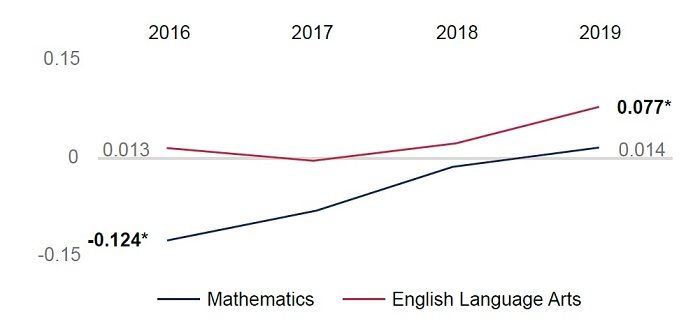

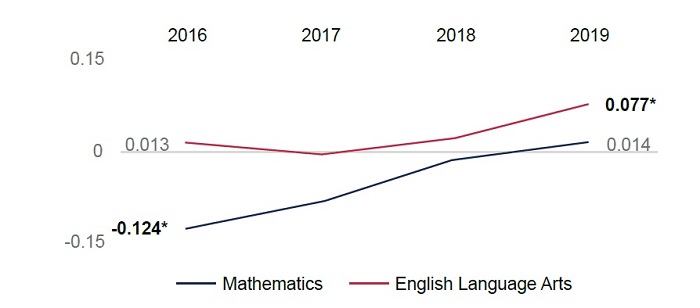

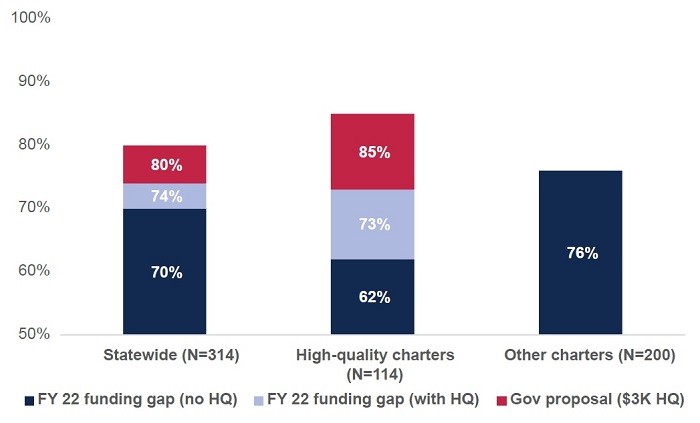

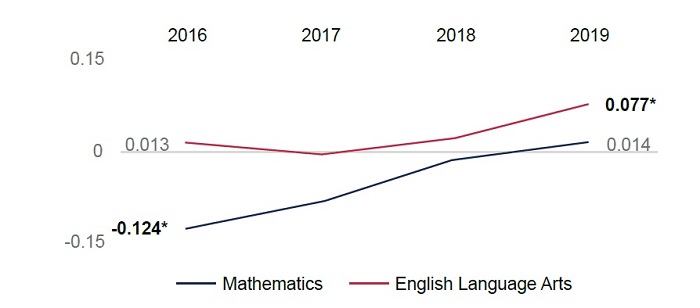

- Improved overall academic performance. Stronger accountability measures have driven higher sector performance. As Figure ES-1 shows, the sector’s impact on student academic growth was roughly even with comparable districts in reading, and significantly below them in math in 2015–16. Three years later, the charter sector outperformed districts in reading, and performed similarly in math.

Figure ES-1: Annual impact of attending an Ohio charter school (brick-and-mortar or online)

Note. The table illustrates improvement in the estimated annual impact of charter school attendance (including e-schools and schools serving students with special needs) on student achievement in grades 5-8. Values displayed in bold and with asterisks are statistically significant at a 5 percent level. Model specifications and tabular results appear in Appendix G.

Note. The table illustrates improvement in the estimated annual impact of charter school attendance (including e-schools and schools serving students with special needs) on student achievement in grades 5-8. Values displayed in bold and with asterisks are statistically significant at a 5 percent level. Model specifications and tabular results appear in Appendix G.

Source: Stéphane Lavertu, The Impact of Ohio Charter Schools on Student Outcomes 2016-19 (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2020).

The second part of this report focuses on charter funding, which also impacts the performance of the sector. Since their debut, Ohio charters have been systematically underfunded, receiving around 65 to 70 percent of the overall taxpayer support of their local districts. This inequity disadvantages charters in competing for teacher talent, limits the extra supports and enrichment opportunities they can provide to students, and constrains their ability to expand and reach more students. Such large shortfalls are fundamentally unfair to charter students, who don’t deserve to be shortchanged purely by virtue of their choice in schools.

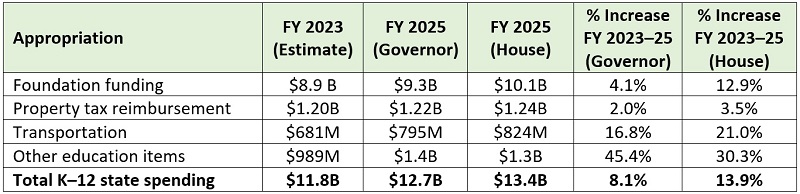

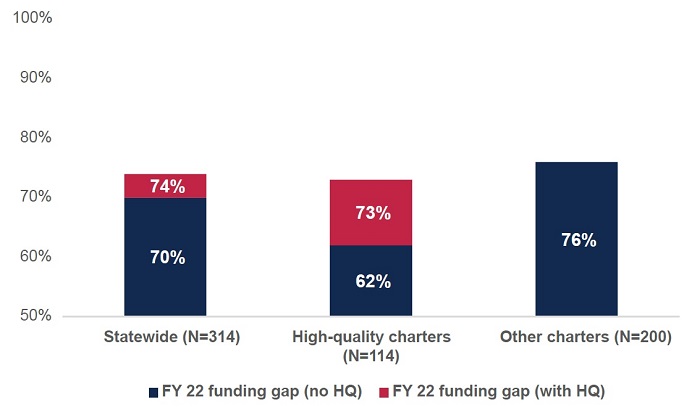

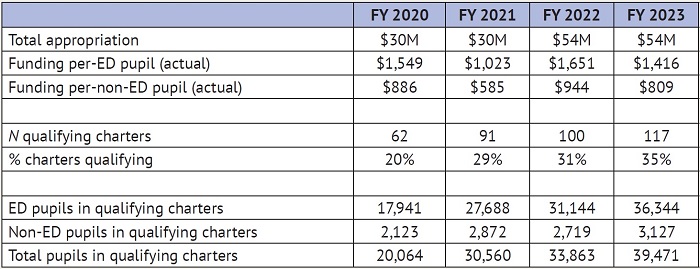

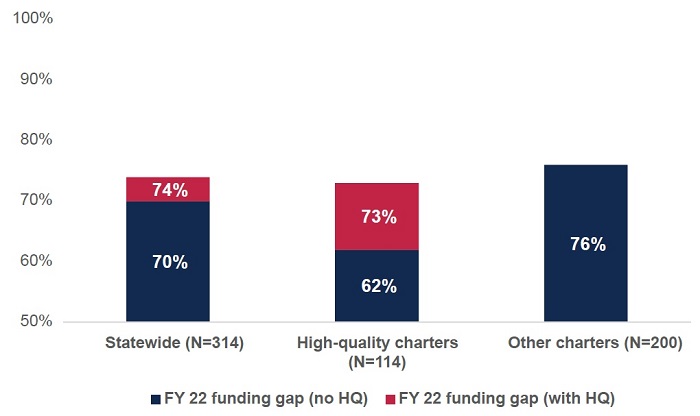

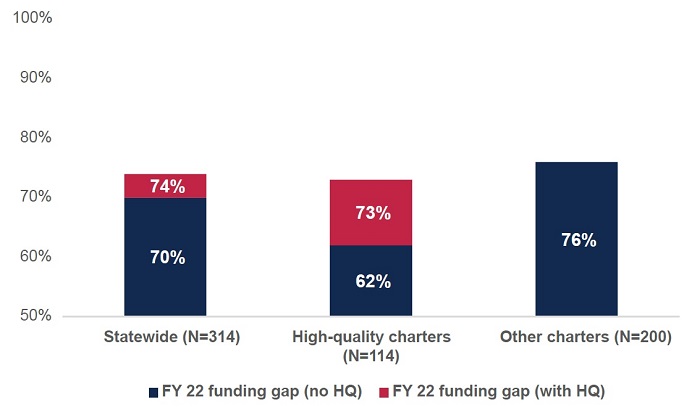

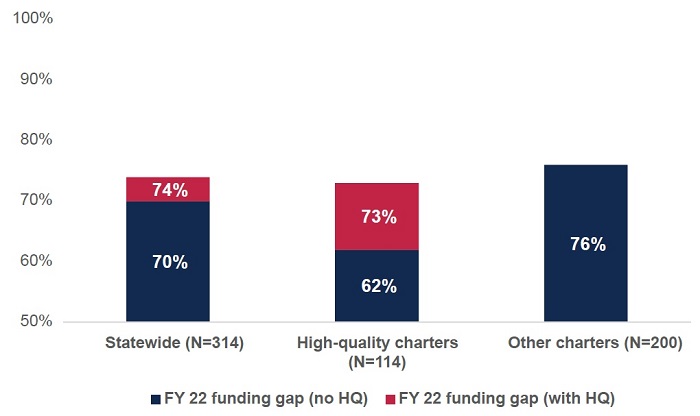

Starting in the 2019–20 school year, Ohio lawmakers took an important step toward equity by launching a supplemental funding program that provides high-quality charters—those earning strong state report card ratings—with up to an additional $1,750 per economically disadvantaged pupil and $1,000 per non-disadvantaged pupil. As Figure ES-2 indicates, this initiative eases the funding gap faced by high-quality charters. Yet, even with these extra funds, Ohio charters have remained underfunded. On average, brick-and-mortar charter schools statewide receive just 74 cents on the dollar in comparison to their local districts, a shortfall that continues to treat charter students as second-class citizens.

Figure ES-2: Charter funding gaps, with and without the high-quality supplement

Note: This figure displays the percentage of state and local funding that Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charters received on average in FY 2022 relative to the districts in which they are located (virtual schools are not included). It displays the existing gaps both with the current high-quality (HQ) supplement and without it.

Note: This figure displays the percentage of state and local funding that Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charters received on average in FY 2022 relative to the districts in which they are located (virtual schools are not included). It displays the existing gaps both with the current high-quality (HQ) supplement and without it.

Strong accountability and equitable funding policies are critical to the health of Ohio’s charter school sector. Within the past decade, Ohio has taken great strides forward in the realm of accountability, but significant work remains to achieve funding parity. As state lawmakers continue to review and refine charter policy, we summarize three recommendations (more specifics appear in the conclusion).

- Keep the pedal to the metal on charter accountability. Ohio can’t afford to slip back into the dark ages of lax accountability and anything-goes in the charter sector. Lawmakers need to maintain the commitment to accountability for sponsors and schools to ensure that student achievement remains a priority and that the performance of the sector continues its upward trend.

- Encourage the expansion of quality charter schools. Now that the accountability bar is higher, policymakers should boldly ratchet up efforts to expand quality charters to meet the state’s continued need for excellent schools. One critical avenue to accomplish this goal is better funding for quality schools. To his credit, Governor DeWine recently proposed a hefty increase to the high-quality charter initiative for FYs 2024 and 2025. Legislators should embrace his proposal, along with other efforts that would help quality charters grow and replicate.

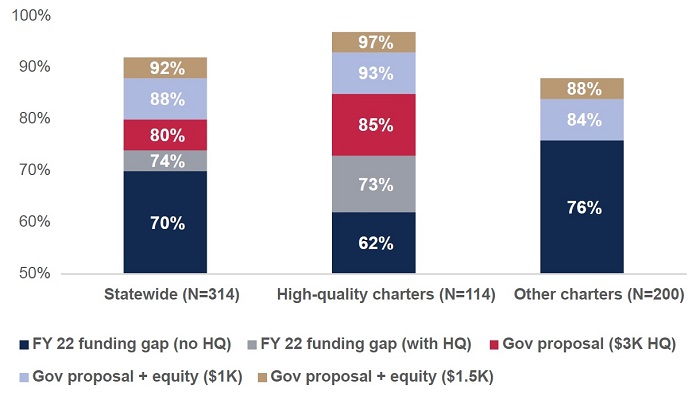

- Provide equitable funding for all brick-and-mortar charters. As a matter of fairness to charter students, Ohio lawmakers should work to fund all charters more evenhandedly. At a minimum, legislators should aim to ensure that all brick-and-mortar charters receive at least 90 percent of district funding. One way to do this would be to create a new “equity supplement” that provides $1,000 to $1,500 per pupil to all site-based charters. If this more generous amount were adopted, the average Ohio charter would receive 92 percent of its local district’s overall funding.

Through much-needed reforms, state lawmakers have reinvented Ohio’s charter school sector. The Buckeye State is no longer the “wild west” of charter schools, as dozens of low-performing schools have closed, and more than forty sponsors have departed. The recent launch of the high-quality fund has also infused top-notch, homegrown schools with some of the extra resources needed to expand, and it has helped persuade quality national charter organizations to make Ohio home, including the highly respected IDEA Public Schools network. With a continued focus on accountability and equitable funding, state policymakers can further brighten the future of Ohio’s charters and the students they serve.

Charter School Enrollment and Demographics

In an effort to reinvigorate public education, give parents more options, and boost lackluster pupil achievement, education advocates and reformers throughout the 1980s and 1990s began proposing autonomous public schools that would operate independently of traditional districts and be free from some regulatory red tape. Lawmakers from both parties found these ideas persuasive, and responded by putting the concepts into real-world policy frameworks. Minnesota passed the nation’s first charter school law in 1991, and six years later Ohio did likewise. Its first charters launched in the fall of 1998, enrolling just over 2,000 students in fifteen schools.

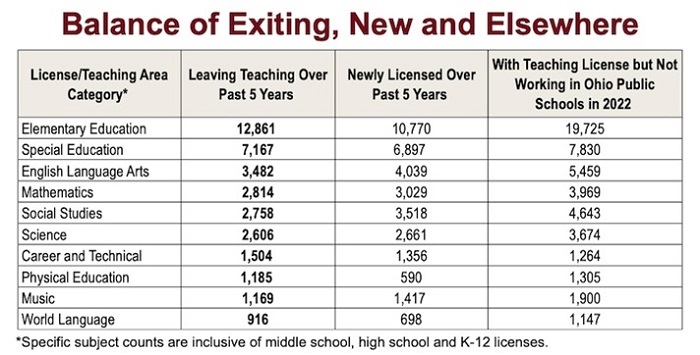

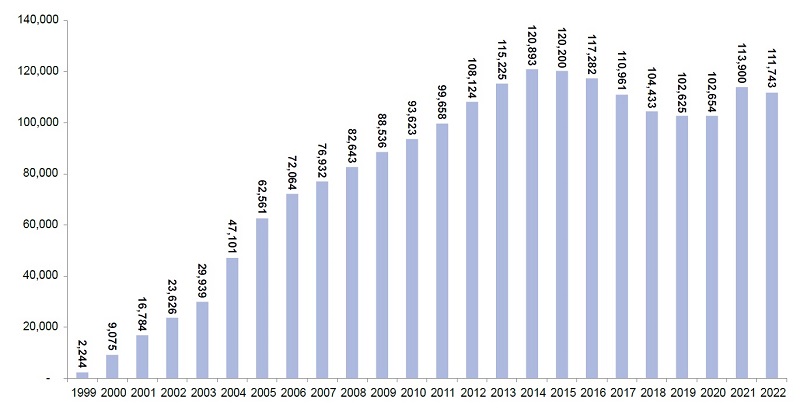

As Figure 1 indicates, Ohio charters grew rapidly between 1998 and 2014, with enrollment reaching almost 121,000 students. That number declined to 102,000 students by 2019, reflecting the closure of dozens of low-performing schools in the wake of the accountability reforms discussed in this report. Charter school enrollment bounced back in 2021 and 2022, helped by an uptick in students attending online charter schools during pandemic-impacted years. In 2021–22, just over 110,000 students (seven percent of Ohio’s public school population) attended one of the state’s 324 charter schools. Approximately 80,000 students enrolled in brick-and-mortar charter schools, while the rest attended one of the state’s fifteen online charters.

Figure 1: Ohio charter school enrollment, 1997–98 to 2021–22

Note: The Appendix displays the number of charter schools operating by year.

Note: The Appendix displays the number of charter schools operating by year.

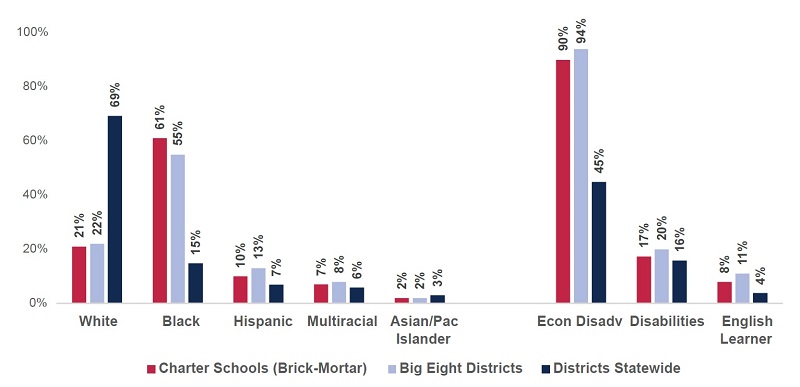

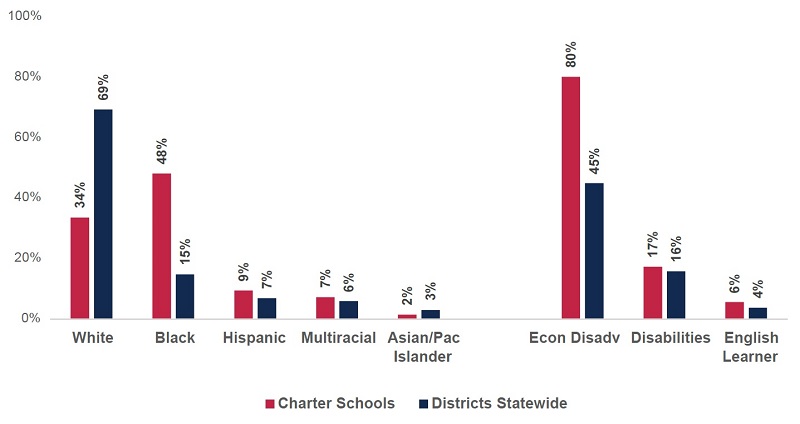

The vast majority of brick-and-mortar charters operate in the state’s major urban areas, the result of a longstanding provision in law that limited charters to certain “academically-challenged” districts (the restriction was repealed in 2021). As a result, Ohio charter schools serve disproportionate numbers of historically disadvantaged students. Figure 2 shows that 59 percent of students attending either an online or brick-and-mortar charter school are Black or Hispanic, compared to a statewide district average of 22 percent. Meanwhile, 80 percent of charter students are economically disadvantaged, compared with 45 percent of district students.

Figure 2: Characteristics of Ohio charter students (brick-and-mortar and online) versus districts statewide, 2021–22

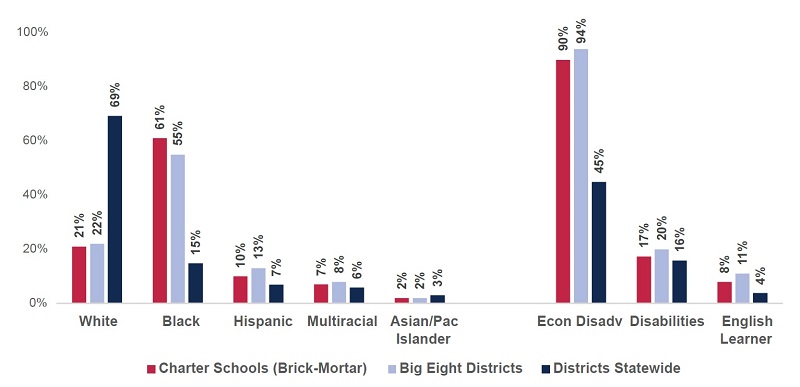

When focusing exclusively on brick-and-mortar charters, the percentage of Black and Hispanic and economically disadvantaged students rises. Seventy-one percent of brick-and-mortar charter students are children of color, while 90 percent are economically disadvantaged. As Figure 3 indicates, these numbers track closely with the Big Eight districts’ demographics—reflecting, again, the fact that most site-based charters are located in those cities. In five of the Big Eight cities—Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown—more than 25 percent of the city’s public school students attend charter schools (the charter shares for each city appear in the Appendix).

Figure 3: Characteristics of Ohio charter students (brick-and-mortar only) versus Big Eight districts and districts statewide, 2021–22

Given that they educate such large proportions of disadvantaged students, charters are a critical part of efforts to narrow longstanding achievement gaps in Ohio (as in many states). As we’ll see later, with strong accountability mechanisms now in place, brick-and-mortar charters have done a solid job boosting the achievement of Black and Hispanic students in recent years. Their demographics are also important context in discussions about whether charters should receive equitable funding, as disadvantaged pupils typically require more resources for their education.

Accountability Reforms and Subsequent Results

One of the central tenets of the charter model has always been greater operational autonomy in exchange for heightened results-focused accountability. Since their debut in 1998, Ohio’s public charter schools have been held accountable through several mechanisms. First, just like traditional public schools, charters receive report card ratings from the state and are subject to school improvement requirements if they are deemed low-performing under federal guidelines. Second, charter schools automatically lose funding when students leave them. If enough parents are dissatisfied and choose to enroll their children elsewhere, charters are forced to close for financial reasons. Third, a state law enacted in 2006 requires chronically poor-performing charters to permanently close, a requirement that does not exist for district schools.[1] Fourth, charter sponsors are directly responsible for overseeing schools and holding them accountable, including potentially closing them for poor performance.

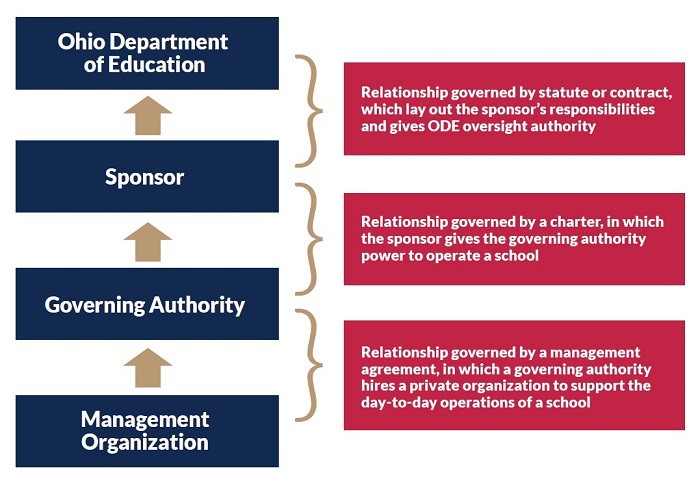

The charter reforms enacted in 2015, via House Bill 2 (HB 2), largely focused on stronger accountability through sponsors; hence, this section focuses heavily on this mechanism. But before delving into the details of HB 2, we must first understand the charter governance model.

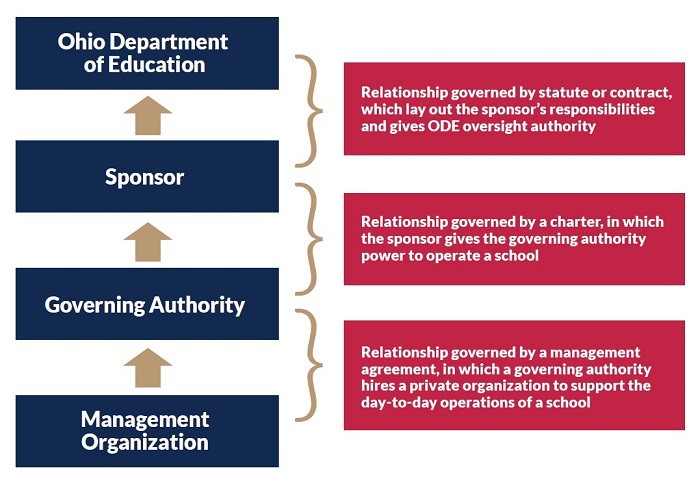

The basic form is illustrated in Figure 4 below. Starting at the individual school level (we will come back to management organizations), each charter has its own governing authority, or “board,” that guides its mission and operations. Akin to a local district school board, the governing authority is responsible for making budgetary decisions, selecting curricula, and choosing a school leader and holding him or her accountable.

Overseeing the school and its board is a sponsor, also known as an “authorizer.” Sponsors permit a charter school to open via contract with the governing authority, and then hold the school accountable for academic performance and compliance with various rules and regulations. Sponsors may non-renew or terminate contracts for poor performance, which almost always results in the closure of a school. Unlike most other states, Ohio allows various types of entities to sponsor charters; they may be a traditional district, educational service center, institution of higher education, an approved nonprofit, or ODE (the breakdown of sponsor types is here). Last, it is important to recognize that although a sponsor does not actually run the school—that’s the role of the board and administration—it can influence the way schools are managed through its oversight and accountability practices.

ODE is responsible for holding sponsors accountable. As discussed below, HB 2 altered the relationship between ODE and sponsors by empowering the agency to more rigorously execute its oversight duties.

Finally, a school’s governing board may choose (or not) to contract with a management organization, which may handle some (or all) of the day-to-day operations of the school. These entities can be for-profit or nonprofit: As of 2019, 47 percent of Ohio charters hired for-profit management organizations, 28 percent hired a nonprofit, and 25 percent of charters chose not to contract with any management group.[2] There is sometimes confusion about the status of a school when it hires a for-profit operator. But under state law, the school itself remains a nonprofit organization. Governing boards have the power to terminate or non-renew a management contract if they are dissatisfied; hence, charter boards are primarily responsible for holding such organizations accountable for results.

Figure 4: Governance structure of Ohio charter schools

Source: Juliet Squire, Kelly Robson, and Andy Smarick, The Road to Redemption: Ten Policy Recommendations for Ohio’s Charter School Sector (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2014).

Source: Juliet Squire, Kelly Robson, and Andy Smarick, The Road to Redemption: Ten Policy Recommendations for Ohio’s Charter School Sector (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2014).

While this general structure has been in place since the inception of charters, loose accountability policies undermined the framework for a number of years. At the top, ODE wasn’t holding sponsors rigorously accountable for the performance of their schools. Some sponsors, in turn, took a lax approach to overseeing schools in their portfolios and instead focused more on using sponsorship as a revenue source for themselves.[3] Charter boards allowed too many poorly run management organizations to continue operating their schools. This cascading effect resulted in uneven academic performance and a sector that—until reforms were enacted—was plagued by questions regarding its ability to regulate itself.[4]

House Bill 2

Concerned about weak accountability and its impacts, Fordham and others began urging state lawmakers to strengthen the state’s charter school laws.[5] Former Governor John Kasich and the 131st General Assembly heeded these calls and enacted comprehensive reforms in 2015 via House Bill 2 (HB 2). Its key provisions included:[6]

- Requiring new and existing sponsors to enter a contract with ODE before operating. To ensure stronger state-level oversight, the legislation requires ODE to vet and approve, via contract, new entities seeking sponsorship. With two exceptions,[7] the legislation also required that all existing sponsors receive ODE approval to continue operation.

- Establishing clear consequences for poor sponsor performance. Ohio launched a sponsor evaluation system just prior to HB 2, but it lacked the teeth needed to produce stronger sponsor-driven accountability for school performance. The legislation established an enhanced evaluation framework that includes clear sanctions for low-performing sponsors. Further explanation of the revamped evaluation system—a crucial reform—begins here.

- Eliminating sponsors’ ability to sell services to schools they authorize. Prior to HB 2, sponsors were permitted to sell supplemental services to their schools, a blatant conflict of interest with their oversight role. Save for school district and university sponsors, the legislation prohibits this practice.

- Reducing the likelihood that low-performing schools “sponsor hop.” Formerly, low-performing schools could switch sponsors to avoid closure when a sponsor non-renewed or terminated their contract. HB 2 now requires low-performing schools to meet several conditions before changing sponsors, including receiving ODE approval for the shift.[8]

- Ensuring that a charter board’s decision to fire a management company is final. Under former law, a management organization could appeal its dismissal to the school’s sponsor or state board of education. This provision directly undermined the authority of the charter board to hold its management organizations accountable. HB 2 wisely eliminated the possibility of appeal.

- Requiring charter school boards to hire an independent fiscal officer and legal counsel. One concern prior to HB 2 was that some charter boards were not conducting arms-length transactions with management organizations. This provision helps ensure that boards are acting independently and in the best interest of the school.

Taken together, these reforms laid the groundwork for a more responsible, higher performing charter sector. The next section looks at how the legislation reshaped Ohio’s charter environment.

Impacts on the charter sector

HB 2 had three major impacts on Ohio’s charter sector. First, it removed dozens of low-capacity sponsors. Second, it led to the closure of a number of low-performing charter schools. And third, it helped to push overall sector performance higher. Let’s look at each in turn.

Removal of low-capacity sponsors

Prior to HB 2, Ohio had more than sixty sponsors in operation, authorizing anywhere from a single charter to dozens of schools. Because these sponsors were weakly regulated, too many failed to follow quality practices and often turned a blind eye to poor school performance. To rein in poor sponsors, lawmakers first established a sponsor evaluation system in 2012.[9] But the initial system was not rigorous enough, and HB 2 significantly strengthened it. The updated evaluation has three equally weighted components:[10]

- Academics: Based on the report-card performance of a sponsor’s schools.

- Compliance: Based on ODE review of sponsor compliance with state laws and regulations.

- Quality practices: Based on ODE review of sponsor adherence to quality authorizing practices.[11]

The state combines sponsors’ scores on these components to determine a composite, overall rating of exemplary, effective, ineffective, or poor. Under HB 2, ineffective sponsors are barred from authorizing new schools and are subject to an improvement plan. Sponsorship authority is revoked if an entity receives either a poor rating or an ineffective rating twice in a three-year period.

In the years immediately after HB 2, many sponsors received low ratings via the toughened evaluation system. In 2015–16, sixty of the state’s sixty-five sponsors received ineffective or poor ratings. The next year, twenty-one of forty-five remaining sponsors received such ratings. By 2017–18, thirteen of the state’s thirty-four sponsors were rated ineffective or poor. The net result, as shown in Table 1, has been a dramatic reduction in the number of sponsors still active in Ohio.

Table 1: Number of sponsors in 2012–13 and 2021–22[12]

Closure of low-performing schools

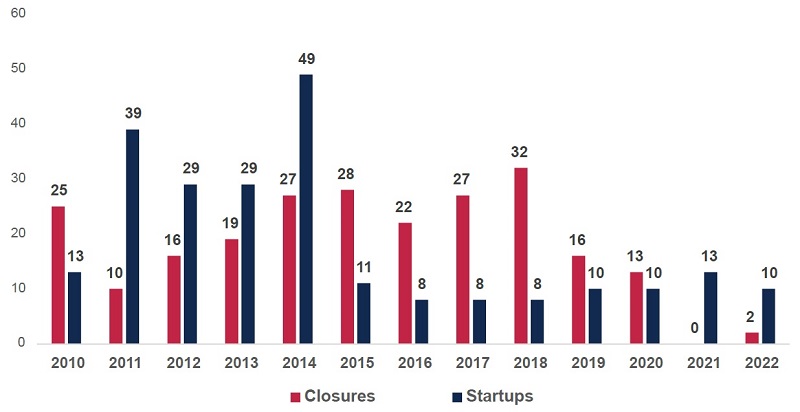

Ohio’s stronger accountability policies not only downsized the number of sponsors, but also pushed remaining sponsors to more aggressively close low-performing schools. Figure 5 shows the large number of charter school closures that occurred immediately after the reforms—112 schools shut down between 2016 and 2022. Closures during this timeframe were driven by sponsors, or by schools themselves, whether for financial, academic, or enrollment reasons or merger with another school.[13] Only one school during this period was closed due to the state’s automatic closure law.

In addition to closures, Figure 5 also shows a significant slowdown in the emergence of start-up charter schools in Ohio. The slowdown reflects accountability reforms that promote more judicious and careful vetting before sponsors permit new schools to open. But it could also reflect the longstanding financial constraints on charters that have made new school formation increasingly difficult, especially as facilities have become scarcer and the competition for talent and students has grown fiercer. The slowdown in charter startups in Ohio also follows the national pattern in the charter sector.[14]

Figure 5: Number of charter school closures and startups between 2010 and 2022

Higher sector performance

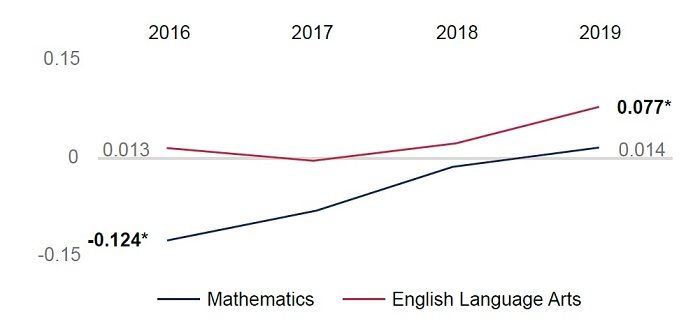

One of the major goals of HB 2 was to improve the academic performance of charter schools. Based on data from the years immediately after its passage, the legislation appears to have accomplished its goal. In a rigorous evaluation that compared charter students’ academic growth on state exams to demographically similar students in district schools, Ohio State University professor Stéphane Lavertu documented a noticeable uptick in charter performance starting in 2015–16. In that year, overall charter performance—including both brick-and-mortar and online schools—was roughly on par with their traditional district counterparts in reading, while the sector underperformed districts in math. By 2018–19, however, charters outperformed districts in reading and were about equal in math. The figure below, drawn from his report, displays the annual learning gains or losses (in standard deviations) of charter students in grades five through eight, relative to comparable students attending district schools.

Figure 6: Academic impact of all Ohio charters (brick-and-mortar and online schools) on student achievement, 2016–2019

Note. The table illustrates improvement in the estimated annual impact of charter school attendance (including e-schools and schools serving students with special needs) on student achievement in grades 5–8. Values displayed in bold and with asterisks are statistically significant at a 5 percent level. Model specifications and tabular results appear in Appendix G.

Note. The table illustrates improvement in the estimated annual impact of charter school attendance (including e-schools and schools serving students with special needs) on student achievement in grades 5–8. Values displayed in bold and with asterisks are statistically significant at a 5 percent level. Model specifications and tabular results appear in Appendix G.

Source: Lavertu, The Impact of Ohio Charter Schools (2020).

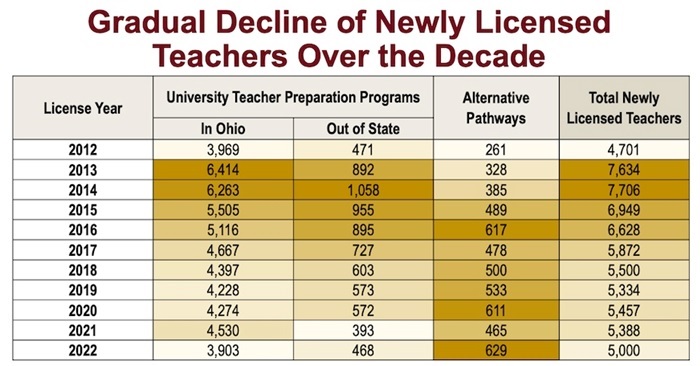

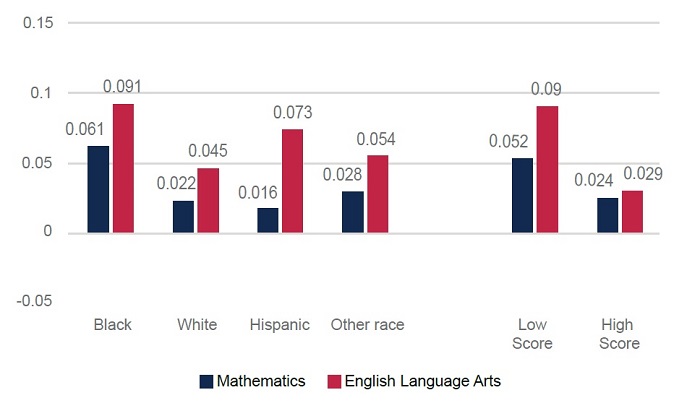

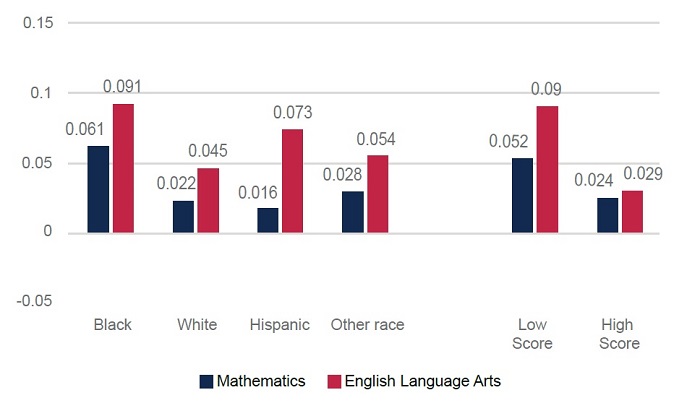

Various studies have found that students attending online schools, whether in Ohio or elsewhere, lose significant academic ground in this educational setting;[15] thus, their results have long weighed down overall charter sector performance. But when the focus is on brick-and-mortar schools, stronger outcomes emerge. Figure 7 shows that Black and Hispanic students attending site-based charters made particularly strong academic progress throughout the period immediately after HB 2 passed. The average Black charter student made learning gains that, accumulated over five years, are equivalent to moving from the 25th to 40th percentile in statewide achievement.

Figure 7: Academic impacts of Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools on math and reading achievement

Note. The table illustrates the annual impact of attending a site-based charter school (as opposed to a traditional public school) on student achievement in grades 4–8. Students with a “low score” or “high score” are those with test scores below or above the statewide mean, respectively. Model specifications and tabular results appear in Appendix B.

Note. The table illustrates the annual impact of attending a site-based charter school (as opposed to a traditional public school) on student achievement in grades 4–8. Students with a “low score” or “high score” are those with test scores below or above the statewide mean, respectively. Model specifications and tabular results appear in Appendix B.

Source: Lavertu, The Impact of Ohio Charter Schools (2020).

Rigorous analyses of charter effectiveness have not been undertaken since the pandemic. However, like their district counterparts, charter students suffered significant learning losses as a result of school disruptions. In general, the losses are comparable to districts. Between 2018–19 and 2021–22, the performance index scores of Ohio’s Big Eight charter schools declined by 14 percent, the same percentage as for the Big Eight districts. Value-added growth results from last year were roughly similar: 31 percent of Big Eight charters received four- or five-star ratings from the state in that realm while 34 percent of Big Eight district schools did so.[16]

As schools emerge from the pandemic and work to address learning loss, policymakers should ensure that charter accountability measures, which were put on pause during the pandemic, are restarted and continue to be rigorously implemented.[17] Reverting back to loose accountability would put charter students at greater risk of academic struggle and likely undo the progress Ohio’s charters have recently made. Moreover, relaxing accountability could also stymie ongoing efforts to improve charter school funding, the topic to which we turn next.

Persistent Funding Gaps

While Ohio has taken major steps forward in accountability, it continues to underfund its charter schools. The bleak situation has existed since charters first appeared on the scene, and it’s caused by a combination of charters’ lack of access to local tax revenues and state funding that does not adequately offset the shortfall. Fordham first documented these funding gaps in a 2004 Dayton-specific study, which found that the city’s charters received just two-thirds of the revenue of the local district. Ten years later, a report from the University of Arkansas showed that the situation hadn’t improved, as charters statewide received on average about 70 percent of district funding. A Fordham analysis published four years ago found similar charter-funding disparities.[18] These analyses mostly focus on operational dollars—e.g., funds used to pay employee salaries and purchase textbooks—but charter schools also lack significant resources for school construction, renovation, and maintenance. A 2021 analysis by Excel in Ed found that Ohio supports just 18 percent of charter facility needs.[19]

In principle, children attending public charter schools ought to receive the same taxpayer support for their education as their peers attending district schools just down the street. Failing to do so is a violation of basic principles of funding equity—a particularly egregious offense given that charter students are disproportionately low-income and students of color. Without equitable resources, charter schools often struggle to provide the extra supports and the enrichment opportunities that students need. They face challenges both attracting and retaining talented teachers in a competitive labor market, as their lower funding levels leave them stuck offering lower salaries. Charters also have less capacity to work to continually improve their educational programs and expand their reach to serve more students.

To their credit, Ohio lawmakers recently took a step forward in bridging the gap by launching the “high-quality charter funding program.” That initiative—championed by Governor DeWine—currently provides up to an extra $1,750 per economically disadvantaged pupil for qualifying schools and $1,000 per non-disadvantaged student. In FY 2023, 117 schools—just over a third of charters statewide—are receiving the supplemental aid. In his latest budget proposal, the governor recommended a significant boost to the program for FY 2024 and 2025. Under his plan, qualifying schools would receive $3,000 per economically disadvantaged student and $2,250 per non-disadvantaged student.

Even with this high-quality fund in place, large disparities persist between charter and district per-pupil operational funding levels. Figure 8 shows that—without the high-quality supplement—the typical Ohio charter received about 70 cents on the dollar compared to their local district in FY 2022.[21] This tracks with previous analyses and indicates that, apart from the high-quality supplement, Ohio has done very little to improve charter funding. When the high-quality dollars are included, the gap narrows slightly, lifting high-quality charters’ funding to 73 percent of their local district and 74 percent for charters statewide.

Figure 8: Ohio’s current charter funding gaps (brick-and-mortar only)[22]

Note: Figures 8–10 display the percentage of funding that Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charters spend on average relative to their local districts in FY 2022. Calculations rely on the state’s expenditure per equivalent pupil data, a measure that weights district and charter schools’ enrollments to account for the extra dollars needed to educate students with disabilities, English learners, and economically disadvantaged students. This measure allows for more apples-to-apples comparisons of spending data than raw per-pupil spending data. To accurately analyze the gap created by state and local funding, federal dollars are excluded from both charter and district spending; transportation expenditures are also subtracted since districts are supposed to transport charter pupils, too. Capital outlay is excluded, but if those dollars were included, the gap would widen as districts receive more dollars for facilities.

Note: Figures 8–10 display the percentage of funding that Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charters spend on average relative to their local districts in FY 2022. Calculations rely on the state’s expenditure per equivalent pupil data, a measure that weights district and charter schools’ enrollments to account for the extra dollars needed to educate students with disabilities, English learners, and economically disadvantaged students. This measure allows for more apples-to-apples comparisons of spending data than raw per-pupil spending data. To accurately analyze the gap created by state and local funding, federal dollars are excluded from both charter and district spending; transportation expenditures are also subtracted since districts are supposed to transport charter pupils, too. Capital outlay is excluded, but if those dollars were included, the gap would widen as districts receive more dollars for facilities.

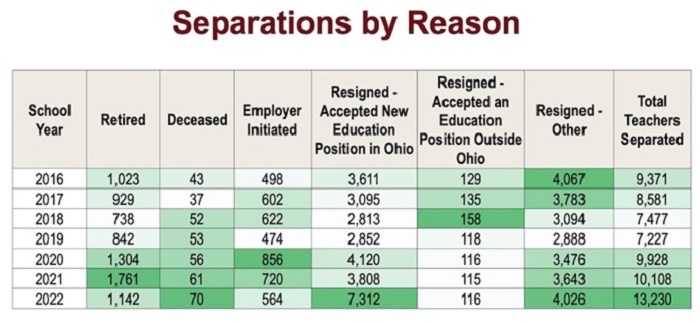

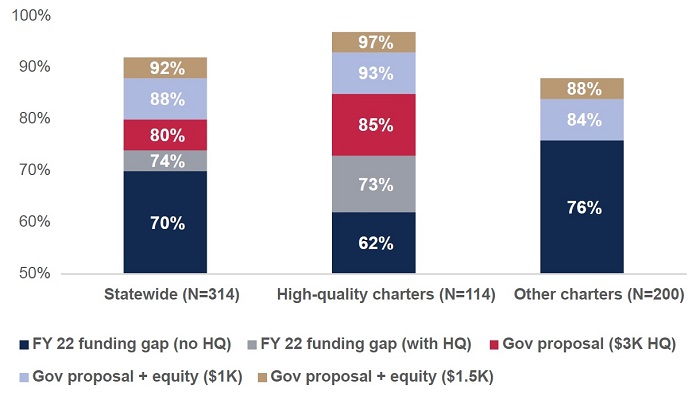

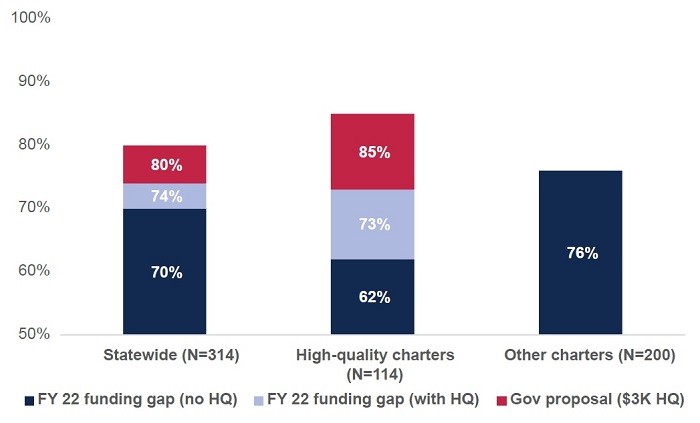

As noted above, Governor DeWine has proposed a significant increase to the supplemental aid that high-quality charters receive. Figure 9 shows the impact of his proposal on the charter funding gap, should it be passed by the legislature. Funding for high-quality charters would be at 85 percent of their local districts, while other charter schools would remain at 76 percent.[23]

Figure 9: Impact of Governor DeWine’s proposed increase to the high-quality fund

The high-quality fund narrows funding gaps for about one-third of Ohio charters, but it doesn’t lend any extra support for schools that do not qualify. Yet students attending these schools still deserve fair funding, especially given the fact that most of the students in non-qualifying schools are economically disadvantaged (82 percent) or students of color (59 percent). The shortfalls in funding limit students’ opportunities, and constrain their schools’ efforts to achieve higher performance as well.

To move Ohio closer to funding parity for all charter students, legislators could create an “equity supplement” that would complement the high-quality program. There are various ways to design such an initiative, but the most straightforward approach is to provide a per-pupil supplement for all brick-and-mortar charters, whether they qualify for the high-quality fund or not. Figure 10 shows the impact of such a program. If Ohio funded the equity supplement at $1,000 per pupil, the charter funding gap statewide narrows to 88 percent of district funding. At $1,500 per pupil, it closes to 92 percent.

Figure 10: Impact of a charter equity supplement

Conclusion and Recommendations

With stronger accountability in place, Ohio’s charter sector has come a long way in a short time. But where next? What else needs doing to turn the sector into the high-gear educational resource that its students need and that the state should demand? Indeed, how can state leaders fully leverage this model to the benefit of more parents and students? We offer three closing thoughts:

- Maintain strong charter accountability, including a rigorous sponsor evaluation system. Ohio’s sponsor evaluation system is the linchpin for accountability in the charter sector. It ensures that sponsors hold schools accountable for results, and in turn that school leaders are focused on improving student learning. But there have been efforts to weaken sponsor accountability since the passage of HB 2, including an unfortunate “tweak” that now allows sponsors to receive an “effective” rating even if they authorize all, or nearly all, failing schools.[24] Lawmakers should consider reversing that policy and could even further strengthen the importance of school performance in sponsors’ evaluations by increasing the weight of the academic component from one-third to one-half. This would sharpen the focus on student outcomes and lessen the need for extensive and repetitive reviews of sponsors’ paperwork. In the end, Ohio needs to maintain this rigorous evaluation system that strongly incorporates academic results and includes consequences for poor sponsor performance.

- Help high-quality schools expand to serve more students. With less than half of Ohio students reaching proficient on rigorous national assessments, and achievement gaps still as wide as they were two decades ago, Ohio continues to need many more excellent public school options. State lawmakers should continue to support the expansion of high-quality charters through various policy avenues. The most critical is better funding, and Governor DeWine’s recent proposal to boost the high-quality charter fund would be a big step forward. His fellow legislators should go a step further by putting the high-quality fund into the overall charter school funding formula, a move that would ensure that per-pupil amounts are not reduced and increase the likelihood that the program is maintained well into the future. Other policy levers to support new school formation include relaxing onerous licensing requirements that prevent quality schools from hiring talented staff and implementing facility initiatives—such as a credit enhancement program—that can help charters secure appropriate classroom spaces.[25]

- Fund all brick-and-mortar charter schools equitably. Simply put, Ohio needs to stop shortchanging charter students just because they attend non-district schools. Ohio’s charter students, like those in several other states, deserve to be treated on equal terms as their district counterparts. Ohio has already made some inroads in fighting this inequity through the high-quality fund. To complete the work, the legislature should take the additional steps needed to ensure that all charter students have equitable funding. As discussed above, an equity supplement that provides all brick-and-mortar charters an extra $1,000 per pupil would narrow the overall charter funding gap to 88 percent of local district funding. A larger $1,500 per pupil supplement would ensure that charters statewide receive on average 92 cents on the dollar compared to their local districts.

Providing charters with equitable funding and holding sponsors and charter schools accountable for results are key ingredients for continued progress in Ohio’s charter sector. To their credit, state policymakers have strengthened both aspects of policy over the years, but work remains to make certain that all charter students receive the world-class education they deserve.

About this report

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute promotes educational excellence for every child in America via quality research, analysis, and commentary, as well as advocacy and charter school authorizing in Ohio. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, and this publication is a joint project of the Foundation and the Institute. For further information, please visit our website at www.fordhaminstitute.org or write to the Institute at P.O. Box 82291, Columbus, OH 43202. The Institute is neither connected with nor sponsored by Fordham University.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my Fordham Institute colleagues Michael J. Petrilli, Chester E. Finn, Jr., Chad L. Aldis, and Jessica Poiner for their thoughtful feedback during the drafting process. Jeff Murray provided expert assistance in report production and dissemination. Special thanks to Nathan Leibowitz who copy edited the manuscript and Andy Kittles who created the design. All errors, however, are my own.

- Aaron Churchill

Ohio Research Director, Thomas B. Fordham Institute

Glossary

Big Eight: The Big Eight districts, identified as such in state law, consist of the public school systems of Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown.

Charter management organizations may be hired by a charter governing board to carry out day-to-day school operations. In Ohio, management organizations are also known as “operators.”

Charter school: A nonprofit, tuition-free, publicly funded school that is governed and operated independently from a local school district. Public charter schools are also known in Ohio as “community schools.”

Charter sponsors allow charter schools to open under a contract with the school’s governing board. Sponsors exercise direct oversight of the school and have the authority to close it by terminating or non-renewing a contract. Sponsors are also known as “authorizers.”

House Bill 2 (HB 2): Passed in 2015, HB 2 of the 131st General Assembly made significant reforms to Ohio’s charter school laws.

Ohio Department of Education (ODE) is the state education agency that implements education laws. The department directly oversees charter sponsors; for some charter schools, it serves as the sponsor.

Endnotes

[1] The automatic closure law is designed more as a “fail-safe” when sponsors refuse to close a low-performing school. Just twenty-five schools have actually closed under this policy—none since 2019—as the statutory criteria require extremely low performance over multiple years. Current law requires charters to close if they receive three consecutive years of poor ratings: https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-revised-code/section-3314.35. The list of charters closed under this provision is available at ODE, Annual Reports on Ohio Community Schools, table titled “History of Closure Under 3314.35.”

[3] Charter sponsors are funded through fees from their schools, which may not exceed 3 percent of a school’s state funding.

[4] CREDO, Charter School Performance in Ohio (Stanford, CA: CREDO at Stanford University, 2014). See also, Jennifer Smith Richards and Bill Bush, “Columbus has 17 charter school failures in one year,” Columbus Dispatch (January 11, 2014); Patrick O’Donnell, “ECOT closing: Sponsor votes to shut online school after state rejects settlement offer,” Cleveland Plain Dealer (January 18, 2018); and Doug Livingston, “School’s out for White Hat: David Brennan’s pioneering for-profit company exits Ohio charter scene,” Akron Beacon Journal (August 7, 2018).

[7] Two longstanding sponsors—Lake Erie West Educational Service Center (ESC) and Ohio Council of Community Schools—are not required to have a written agreement with the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) unless they receive low sponsor ratings for two consecutive years.

[10] HB 2 and prior law required annual evaluations of sponsors; however, subsequent legislation passed in 2021 now allows effective or exemplary sponsors to be evaluated once every three years while ineffective sponsors continue to receive annual evaluations.

[11] The quality practices rubric is informed by the National Association of Charter School Authorizer’s sponsorship standards as well as Ohio policy. For more, see Ohio Department of Education, “2022–2023 Sponsor Quality Practices Rubric.”

[12] The 2012-13 data are from Squire, Robson, and Smarick, The Road to Redemption (2014). The 2021–22 numbers are from ODE’s webpage, “Overall Sponsor Ratings.”

[13] ODE provides short explanations about why a school closed in its “Closed Community Schools” file available at https://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Community-Schools. Among the reasons include “contract non-renewed,” “closed by sponsor,” “financial viability,” and “declining enrollment.” A handful of schools also closed when their sponsor closed.

[15] See June Ahn, Enrollment and Achievement in Ohio’s Virtual Charter Schools (Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2016); Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO), Online Charter School Study (Stanford, CA: CREDO, 2015); and Sarah A. Cordes, “Cyber versus Brick-and-mortar: Achievement, Attainment, and Postsecondary Outcomes in Pennsylvania Charter High Schools,” Education Finance and Policy (2023).

[17] Sponsor evaluations and the state’s automatic closure law, for instance, were suspended for 2019–20, 2020–21, and 2021–22.

[18] Public Impact, School Finance in Dayton: A Comparison of the Revenues of the School District and Community Schools (Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2004); Larry Maloney, Charter School Funding: Inequity Expands, Ohio Profile (Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas, 2014); and Aaron Churchill, Shortchanging Ohio’s Charter Students (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2019).

[20] The out-of-state performance criteria include schools with an operator that has received a federal startup grant, funding from the Charter School Growth Fund, or have a school in another state that outperforms its local district. More information about the fund is available at ODE’s webpage “Quality Community School Support Fund.”

[21] The higher baseline gap for high-quality charters vis-à-vis other charters (62–76 percent) is explained by lower average spending in high-quality schools.

[23] This does not include the proposed increase in charters’ facility allowance from the current $500 to $1,000 per pupil. Those dollars are excluded in this analysis since it focuses on operational expenditures (not capital outlay).

[24] Prior to 2022, sponsors could not earn an effective or above rating if they received zero points on any of the three components. This was changed in House Bill 583 of the 134th General Assembly. Now a sponsor can receive zeroes on the academic portion and still receive an effective rating through satisfactory scores on the paperwork-driven quality practices and compliance components.