Introduction

Despite astronomical graduation rates, too few Ohio students exit high school prepared for what comes next. Just 24 percent of the state’s graduating class of 2021 met college-ready standards on the ACT or SAT, and only 8 percent earned industry-recognized credentials. Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)—the “Nation’s Report Card”—consistently show that fewer than half of students are reaching proficiency in math and reading. On the most recent round (2022), just 33 percent of Ohio eighth graders reached that benchmark in reading and only 29 percent were proficient in math.

Mediocre outcomes such as these have sparked great debate about how to put more students on surer pathways to success. Some public school advocates continuously assert that more money is the answer. But funding has risen while achievement has not, and that’s the case even more in the wake of the Covid pandemic. In 2021, the average Ohio school district spent more than $14,000 per pupil—up from the roughly $11,000 per-pupil average in 2000.[1] Funding will continue to escalate in FYs 2024 and 2025, as state lawmakers recently provided a hefty boost in district funding via the newish Cupp-Patterson funding formula.

Yet adding money is likely to disappoint in the absence of other serious K–12 education reforms. On that count, Ohio has taken some commendable steps forward by developing rigorous state learning standards and a transparent report card that sheds light on student progress. Lawmakers have also expanded educational choice, which empowers parents to engage more directly in their child’s education and—through heightened competition—pushes all schools to improve. Just this year, state lawmakers enacted historic policy improvements that bolster the state’s public charter and expand access to private schools; these initiatives will further advance choice and competition.

Such moves are intended in part to incentivize stronger performance in traditional public school systems. Yet efforts to directly reform the way districts are governed and managed are often left undiscussed, despite their potential to boost student outcomes, perhaps even more dramatically than the incentives noted above.

Though politically challenging, state legislators interested in such achievement boosts should consider efforts to modernize today’s school district. Teachers working in districts are too often treated like widgets—not the professionals they are—as their performance, talent, and hard work have no bearing on their pay. Job protections shield poor-performing employees from discipline or removal, inhibiting student learning and damaging organizational morale. Sprawling union contracts tie the hands of school leaders, making it nearly impossible to effectively manage their staff to meet pupil needs. To top it off, archaic election laws weaken community-driven oversight and accountability for district leadership and instead allow special interest groups—most notably local unions—to exert outsized influence. Facing little electoral pressure from parents and the general public, school boards tend to avoid pressing for much-needed changes that put students first.

Through bold reforms, state lawmakers can pave the way for district schools whose eyes are on the prize: higher student achievement. The recommendations in this report seek to address state policies that erode local accountability for performance while impeding effective management of district schools. The recommendations are based on the following principles:

- Accountability: Leaders and educators at all levels—from school board to classroom—should be held accountable for increasing student learning.

- Autonomy: District leaders should have the authority to develop and manage teams of talented, dedicated educators.

- Excellence: Schools should value, incent, and reward strong employee performance.

In sum, state lawmakers should strive for a high-accountability, high-autonomy district sector. This approach, which some have described as “tight-loose”—tight on ends (student outcomes) but loose as to means—would be more consistent with the thinking of prominent education scholars and adhere to international research suggesting that nations with highly accountable yet autonomous school systems deliver better student outcomes. It would also follow studies from various locales in the U.S. that find public charter schools, which operate under this basic concept, outperform their district counterparts.

It’s true, of course, that structural changes alone are no cure-all for the inadequate performance of much of public education. Curricular and instructional reforms—some of which are already underway with the current moves to follow the science of reading—are also critical. So, too, are effective student supports, smart budgeting, and (as noted earlier) rigorous state accountability systems and quality educational choices. But a policy framework that promotes strong district governance and dynamic management remains an essential piece to the overall puzzle.

With student achievement floundering and made worse by the pandemic, there’s no time to lose. Transforming the traditional school district will be yet another step toward the education outcomes—and brighter future—that Ohio’s children need.

Holding school boards accountable

School boards play a central role in district governance. They are responsible for hiring the superintendent and treasurer, then overseeing and evaluating their performance. Boards adopt textbooks and curricula, craft and approve budgets, and decide whether to put local tax requests on the ballot. Together with administrators, they negotiate employment contracts with the unions. They set priorities and policy for the district, monitor progress, and respond to concerns from parents, employees, and community members. Despite these weighty responsibilities, board members receive little to no compensation, and some put in long hours reviewing materials, responding to constituents, attending meetings, and appearing at school events.

Although school board members are a step removed from teaching and learning, they set the tone for the district and influence what happens inside classrooms. Some do an exemplary job—exercising the type of leadership that moves the needle on pupil achievement—but others get mired in petty politics, micromanagement, and excuse making, setting the stage for an organizational culture rife with low expectations (a 2014 Fordham Institute study showed a link between more academically focused school boards and higher pupil achievement).

Given boards’ influence and authority over their districts, state lawmakers should help communities hold members accountable for improving student outcomes. Yet weaknesses in current law undermine citizen-driven accountability and shield board members from scrutiny. To strengthen accountability, we suggest the following:

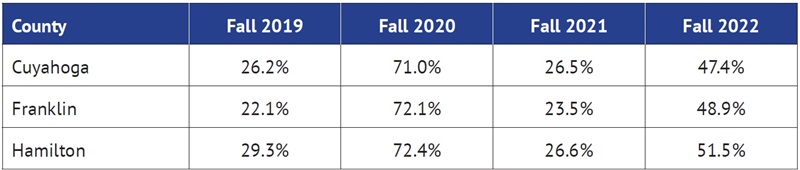

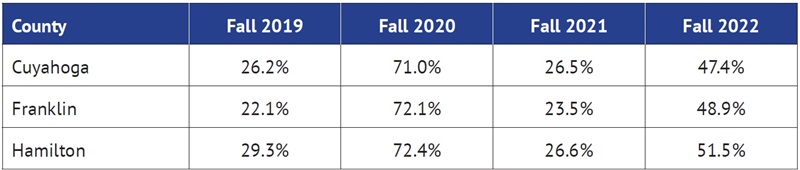

- Schedule school board elections on cycle. The traditional mechanism for holding school boards accountable is through the ballot box. If local voters are frustrated with district performance, they can and should select new members. The Ohio Constitution calls for “off-cycle” school board elections—i.e., taking place in odd-numbered years when national and statewide elections are off the ballot. Such timing dramatically reduces voter turnout: Just a quarter to a third of voters head to polls in off-cycle elections, whereas half to three-quarters vote in on-cycle elections. Table 1 shows the sharp differences in voter turnout across Ohio’s three largest counties. In Cuyahoga County, for instance, just 27 percent of registered voters participated in the fall 2021 off-cycle elections when school board races were contested. Meanwhile, 71 percent of the county’s voters went to the polls in fall 2020—a presidential election—and 47 percent voted in fall 2022 (midterms).

Table 1: Voter turnout rates for off-cycle (2019 and 2021) and on-cycle (2020 and 2022) elections Source: Cuyahoga, Franklin, and Hamilton County boards of elections

Source: Cuyahoga, Franklin, and Hamilton County boards of elections

Low-turnout contests tend to favor certain segments of the electorate rather than the general public. Analysts have found that off-cycle school board elections give undue sway to district employees who are highly motivated to elect candidates sympathetic to their concerns (e.g., higher pay or easier work conditions). Though it would require significant legislative support and, ultimately, voter approval via statewide referendum, moving board elections on cycle would change this dynamic by significantly increasing public participation and encouraging boards to pay attention to the concerns of the broader community. Accountability for board members’ decisions would also increase, as they could no longer count on sleepy elections to stay in office so long as they satisfy special interest groups whose goals are not always aligned with the best interests of students.

- Include candidates’ party identification on the ballot. School board races in Ohio are technically nonpartisan under state law, and candidates’ party identification is omitted from the ballot. Without a “cue” about where candidates likely stand, the only thing a voter may know about a candidate is a name or how many yard signs he or she has—hardly sufficient information to make an informed choice. Suppressing party identification also weakens accountability for incumbents, as voters cannot identify which party holds the board majority. If candidates’ party affiliations were revealed, dissatisfied citizens could vote in a manner that seeks to shift control of the board. As occurs in Louisiana and Pennsylvania, Ohio should require party identification to appear on the ballot for school board elections, so that time-constrained citizens—not just political “insiders,” often those with union ties—have some baseline information about the candidates and their likely leanings. A primary election process, however, should not be used to nominate board candidates, thus allowing multiple candidates from each party and independents to run. Of course, state and community leaders should continue to encourage Ohioans to learn more about board candidates by attending town halls, reviewing campaign literature, and directly engaging with those running for office.

- Increase modestly the maximum allowable compensation of board members. Ohio’s local school board members are currently paid very little, if anything. Statute sets a maximum compensation of just $5,000 per year. While most board members likely see the position as community service, poor compensation could easily discourage talented community members from seeking the position. It might even cost them more to serve on the board—counting time, travel, childcare, and more—than they receive in compensation. Predictably, many board races go uncontested each cycle, with incumbents unopposed or only weakly challenged. In the fall 2021 elections, four Franklin County districts had uncontested board races (three candidates vying for three seats), while three more had weakly contested races (four candidates for three seats). Increasing the maximum pay would be more consistent with the responsibilities and commitments of a board member. It could also remove a financial barrier to working-class individuals and busy parents who seek to pursue the office. One potential way of structuring board compensation is to create multiple tiers based on district enrollment and the likely commitments of the position—e.g., max compensation of $10,000 for districts with more than 10,000 students; $8,000 for districts between 5,000 and 10,000; and $6,000 for districts below 5,000 students. Florida, for instance, structures its school board compensation policy in this way, so that members of larger districts receive higher compensation than their counterparts overseeing smaller ones.

- Include a statement about improving student achievement in the oath of office. Under state law, board members must affirm an oath of office that includes upholding the U.S. and Ohio constitutions as well as faithfully performing the “duties of his office.” Those are essential provisions. But, as suggested in this scholarly article, the oath should also include a statement about improving student outcomes. Pledging school board members to such a goal would make clear that one of their highest obligations is to benefit students. It could also make increasing achievement more central to board debates and reelection campaigns.

Creating fairer local tax referenda

On average, Ohio districts generate 43 percent of their total funding from local taxes, with the rest coming from state and federal aid (41 and 9 percent, respectively) and nontax revenues (7 percent). Local dollars are raised primarily via property taxes, which a third of Ohio districts supplement with local income taxes. Save for minor exceptions,[2] local voters must approve these taxes through ballot measures initiated by district boards. Ohio law requires all districts to levy a minimum twenty mill (or 2 percent) property tax rate in order to qualify for state aid, and voters in virtually all districts have approved tax rates above that floor. In 2022, districts’ effective property tax rates ranged from 2.0 to 8.3 percent, with a statewide average of 3.5 percent.

The local levy system generates billions of dollars for districts and remains a key aspect of school funding. Yet the referenda requirement also serves as an accountability check, as residents can express their support (or not) of the district through these ballot measures.

In a fair election, neither proponents nor opponents of a district tax request would receive a built-in advantage from state policy. The tax question on the ballot, for example, should be presented in neutral and understandable language. To their credit, lawmakers recently made changes to ballot language that now require a clearer presentation of the proposed cost to homeowners. Yet Ohio law still provides subtle edges to those who want higher taxes. This tilted playing field weakens accountability, as districts can rely on those advantages that make it easier to pass a levy. To create a more even playing field, we recommend the following:

- Tighten requirements for an emergency levy. Ohio law allows districts to seek an “emergency levy,” one of several types of levies that districts may put on the ballot. Surprisingly, districts need not be in state-defined fiscal distress to propose this type of levy. In fact, a district need only claim that it’s seeking the dollars “to avoid an operating deficit,” regardless of the size of the projected shortfall or whether the district could balance its budget by adjusting expenditures. Roughly one-third of Ohio districts—212 of them in 2022—imposed an emergency levy, even though just two are in fiscal distress. One district not in fiscal distress is Cincinnati Public Schools, yet it passed an emergency levy in fall 2022 while at the same time spending $18,075 per pupil that year (23 percent above the state average). Districts shouldn’t be able to frighten or mislead voters into a yes vote through “emergency” terminology. Unless they are in an actual state-determined fiscal emergency, districts should be required to propose more neutrally framed funding requests.

- Restrict districts to one levy request every twelve months. In tax campaigns, districts sometimes try to coax voters into approval by threatening to put the levy—should it fail—on the ballot again. Without restrictions on how often districts can go to the ballot, some follow through on their “promise” and ask voters to approve tax requests multiple times in short duration. Ross Local School District, for instance, recently put a levy on the ballot three times within one year. Preble-Shawnee Local Schools put six tax requests on the ballot within a six-year window—twice each in 2017 and 2020—before it finally passed a levy in 2021 (“sixth time’s the charm,” said the local superintendent). The unfettered ability to return to the ballot is unfair to opponents of tax referenda, and the repeated attempts can wear down voters into grudgingly approving it. State lawmakers should make sure that “no” votes—a measure of citizen-led accountability—are better honored by limiting districts to one tax request every twelve months.

- Require tax rates and levy histories to be posted on a district’s report card and its own website. Ballot language discloses the amount of the proposed levy but not the total tax burden that voters face if it passes. For instance, a district may propose a property tax hike of five mills (0.5 percent), but voters have no information—at least not via the ballot—about their existing tax rate (which might already be twenty-five mills or more). While the ballot itself could include preexisting tax rates, doing so would increase the length and complexity of the question. Instead, legislators should require districts’ local tax rates (along with comparisons to state averages) and levy histories to appear in the financial section of their state report card so that voters have easier access to important background information before they head to the polls. Districts should also be required to disclose these data on their own websites.

Advancing excellence in the office of superintendent

Each school board must appoint a superintendent who, alongside the board, develops district priorities and strategic plans as well actually managing the district. The superintendent is typically the highest-paid employee of the district—often earning well into six figures—and he or she exercises leadership in a wide variety of areas. This often includes recommending curricula and instructional programs, negotiating employment contracts with the unions, forging partnerships with community organizations, and fielding concerns from educators, parents, and citizens.

Much like board members, superintendents are a step removed from the classroom, but their work strongly influences both the culture and practices of the district. Nationally, several big-city districts have benefitted from strong superintendents, some of whom came from nontraditional backgrounds such as law, politics, the military, or nonprofit management. Such leaders include Joel Klein in New York City, Arne Duncan in Chicago, Mark Roosevelt in Pittsburgh, and Mike Miles, the recently appointed superintendent in Houston.

Although advancing excellence in the superintendency is an important goal for Ohio, today’s state policies foster weakness in the central office. School boards, for instance, are not required to conduct rigorous annual evaluations of superintendents, nor can they dismiss a superintendent without jumping through a multitude of regulatory and legal hoops. There are also significant entry barriers to the job; as a result, superintendents typically come from educator ranks—a background that may or may not provide the skills and experience needed to run large, complex organizations. As former Cleveland superintendent Eric Gordon said in a recent interview, “Honestly, a superintendent’s license did not prepare me for this job. . . . So I actually had to park a lot of my academic officer skills and focus on other things, like the finances, like talent, like the infrastructure, the organizational structure, public trust, the politics, all of these other things that they didn’t teach me in superintendent school.”

To create the potential for boards to engage real “chief executive officers” for their districts, we propose the following:[3]

- Remove unnecessary licensure restrictions. Current state law requires district boards to hire individuals with a superintendent’s certificate, the requirements for which are extremely restrictive. For example, as a prerequisite for a traditional superintendent license, an individual must hold a master’s degree and have previous experience being a teacher as well as a principal or central administrator. These criteria all but eliminate the possibility of hiring superintendents from other fields and backgrounds. Ohio does allow school boards to hire nontraditional superintendents under a temporary, two-year alternative license that can be renewed once. But that route includes its own onerous requirements, such as completing additional coursework to move to a permanent license, along with time-consuming professional development while serving under the alternative license. Those hurdles likely discourage external leaders from considering the job—and boards from seeking them. State lawmakers should revamp superintendent licensing to allow districts to more easily hire nontraditional candidates. Individuals with a master’s degree or higher and with at least ten years of professional experience should be allowed to apply for a standard superintendent license. This would permit school boards to hire professionals with MBAs, JDs, and PhDs as their superintendent, without any further requirements. University governing boards sometimes hire “outsiders” as president. Ohio State University, for example, just hired a decorated military veteran, and the University of Florida recently hired a former U.S. senator. Why shouldn’t school boards be able to pursue a leader with those types of backgrounds?

- Allow district boards to more easily dismiss a superintendent. Many top government and private-sector leaders serve at the pleasure of their appointing authority and can be dismissed without formal justification. But this is not the case with district superintendents in the Buckeye State. While a school board may terminate a superintendent’s contract before it expires, it must do so for “good and just cause.” Though this may seem sensible on its face, the provision allows for long and expensive legal proceedings that could pit the board against a dismissed superintendent who believes his or her firing is not “good and just.” These job protections for superintendents weaken boards’ authority and discourage removal, even if they have serious concerns about a superintendent’s leadership. State lawmakers should make clear that boards can remove superintendents without undue legal burdens, in essence treating superintendents as an at-will employee.[4]

- Require annual superintendent evaluations that include consideration of student achievement—and make evaluations public. Current state law requires district boards to have some type of evaluation process for the superintendent, but how and when that’s done are left entirely to the discretion of the board. A recent news story from Southwest Ohio indicates that some boards do perfunctory reviews of superintendents—one district had a one-paragraph evaluation—and a few didn’t even bother to complete a written evaluation. That’s just unacceptable. State lawmakers should ensure that boards adopt an evaluation that includes an academic element based on student outcomes (though specific targets should be board determined). Legislators should also clarify that boards must conduct an annual evaluation. Finally, as a matter of transparency, boards should be required to make public the evaluation rubric as well as the results of their evaluations. This would hold boards more accountable for implementing a rigorous review while also putting some healthy pressure on the superintendent to perform.

Letting district leaders lead

In Jim Collins’s classic management book Good to Great, he argues that the first and most critical job of organizational leaders is to get the right people on the bus—and the wrong people off. He explains, “Your best ‘strategy’ is to have a busload of people who can adapt to and perform brilliantly no matter what comes next.” That’s wise advice, not only in business and industry but also for education leaders.

Unfortunately, a complicated web of Ohio state policy constrains district leaders’ ability to get the right people aboard. Rigid, seniority-driven salary schedules handcuff leaders who wish to pay competitive salaries in an effort to attract early- and mid-career professionals, to reward their finest teachers, and/or to persuade them to take the toughest assignments in the most challenging schools. Unwieldy administrative hurdles make dismissing poor performers arduous and expensive. Union contracts, which can cover almost any issue under the sun, make it hard to maintain workplace discipline and build a professional, results-driven organizational culture.

Rather than tying their hands, state lawmakers should empower district leaders to effectively manage their teams. Ohio law, after all, declares that school boards “shall have the management and control of all of the public schools . . . that it operates in its respective district.” Less prescriptive staffing regulations would not only follow this legal precept but also align more closely with the management practices found in other realms of society. It would also likely find support among Ohio’s district superintendents, as strong majorities expressed support for more flexible HR policies in a 2011 Fordham survey. Though not entirely successful, former Governor Kasich pushed hard for serious reforms to school management, and state leaders continue to voice interest in—and have taken some steps toward—giving public schools greater flexibility in hiring and staffing.

Most importantly, better school management is likely to improve student outcomes. Studies from Wisconsin and Florida find that achievement rose when district leaders were given more authority over teacher compensation (WI) and dismissal (FL). Public charter schools are freed from some of the burdensome staffing regulations that districts face, and there is strong evidence from across the nation that charters outperform their less-autonomous district counterparts. To free district leaders to effectively manage the workforce—and to promote a culture of high performance—lawmakers should do the following.

- Repeal districts’ ability to waive management rights and narrow the scope of collective bargaining. Ohio law delineates specific “inherent” management rights of district leadership, which include the ability to “direct, supervise, evaluate, or hire employees” and “effectively manage the workforce.” Yet that same section of law allows districts to give away these rights through the collective-bargaining process, and it also permits negotiations over the “terms and conditions of employment” (in addition to wages and hours). Taken together, these provisions open the door to haggling with unions over myriad workplace issues, including class size, employee transfer and attendance policies, evaluation procedures, disciplinary processes, and more. Dayton Public Schools’ contract, for instance, outlines extensive formal disciplinary procedures that school leaders must follow if they seek to address employee misconduct—red tape that could easily discourage them from taking corrective action.[5] District leadership should ultimately be responsible for establishing workplace rules and job expectations. To ensure this happens, state lawmakers should remove the provision allowing district boards to agree to policies that erode managerial authority. They should also narrow the scope of collective bargaining to wages and hours, as do states such as Indiana and Montana.[6] Such changes would make clear that basic management responsibilities are nonnegotiable.

- Eliminate mandatory step-and-lane teacher-salary schedules. Ohio law requires districts to adopt salary schedules based on teachers’ seniority and college credits earned. Hence, districts must pay their senior teachers more even if they are not as effective or are teaching in less demanding subjects or schools. This policy also mandates substantial salary bumps when teachers receive a master’s degree, despite the scant evidence that a master’s degree enhances effectiveness. This pay system thus ignores an individual teacher’s contributions to student learning, specialized skills, and willingness to work in more challenging environments. It also severely limits district leaders’ ability to recruit and retain talented young people or mid-career professionals, as they are forced to begin their careers at the bottom of the pay scale and are locked into meager annual raises thereafter. To address these issues, state law should be silent on teacher salary[7] and permit district leaders to pay teachers based on merit and other important factors unrelated to seniority or credits earned. Districts could continue a step-and-lane pay policy, but that would be by choice rather than compulsion.

- Remove coursework requirements for teacher tenure and instead make strong performance evaluations a condition for eligibility. Statute outlines several conditions that teachers must meet to be eligible for tenure—i.e., employed under a “continuing contract” that provides significant job protections during their entire career.[8] In addition to holding an educator license for at least seven years, most teachers[9] must complete a whopping thirty semester hours of additional coursework to be eligible for tenure. Like the credits-earned dimension of the salary schedule, this is another perverse incentive for teachers to sit through more coursework and pursue expensive credentials that don’t clearly benefit students. Instead of tying tenure to coursework, state lawmakers should make satisfactory evaluations a condition of tenure eligibility. As recommended by the National Council on Teacher Quality and implemented by states such as Michigan and Tennessee (and to good effect in the Volunteer State, per one recent study), Ohio should move to performance-based criteria for tenure. In addition to finishing a seven-year probationary period—a lengthy term that Ohio lawmakers, to their credit, put in place in 2009—nontenured teachers should need to receive a rating of “skilled” or “accomplished” (the two highest ratings) on their two most recent years of teaching to be eligible for tenure. This approach would ensure that teachers demonstrate instructional effectiveness before receiving job protections.

- Make dismissal of low-performing principals and teachers less onerous. Much like superintendents, school principals and tenured teachers are entitled to extensive hearings and appeals processes that may require their employers to demonstrate “good and just cause” for a dismissal. These administrative hoops—faced neither by most private employers nor by most charter and private schools—discourage district leaders from dismissing ineffective employees, as it’s not absolutely clear that poor performance constitutes “good and just cause.” Following the lead of states such as Florida and New York, Ohio legislators should clearly articulate that ineffective leadership and instruction is grounds for termination, thus removing the possibility that a district’s decision is overturned on appeal. State lawmakers could, in fact, simply extend to all districts a statute that currently provides the Cleveland school board with “just cause” to terminate a principal or tenured teacher who receives poor evaluations.[10] Districts could still be required to demonstrate cause for other reasons, such as alleged misconduct. But making sure that poor performance is clear grounds for dismissal would provide stronger backing to district leaders seeking to remove ineffective principals and teachers, while also putting teeth into the state’s principal and teacher evaluation systems.

- Eliminate last-in, first-out provisions based on tenure status. Tenured teachers also have job protections in cases where a district pursues reductions in force because of enrollment declines or financial reasons. Under a last-in, first-out type of policy, districts are forced to lay off nontenured teachers before those with tenure.[11] This continues a “quality-blind” approach to layoffs, as performance is not considered in the first (and perhaps only) cut. Only tenure status matters. Instead of basing layoffs on tenure, lawmakers should require districts to first lay off “ineffective” teachers within a teaching field—those who receive the lowest rating in their annual evaluations—and then move to “developing” teachers, the second-lowest mark. This would allow district leaders to retain effective teachers, regardless of their tenure status.

Conclusion

Traditional public school systems continue to educate a large majority of Ohio students, yet too many students still leave high school ill prepared for their next step in life. Education reformers have long insisted that one factor behind these mediocre outcomes is a district governance model that tends to put adult school employees’ interests above parent and student needs. They are spot on, and the urgent need for change is even felt by those leading public school systems. In a 2011 survey of Ohio superintendents, strong majorities expressed support for measures such as repealing step-and-lane teacher-pay systems and reigning in collective bargaining. In a scorching resignation letter from 2018, a former Columbus City Schools board member stated quite plainly that the district governance structure is “completely inadequate.”

Regrettably, not much has changed since then. Collective bargaining over all sorts of workplace issues is still a fact of life in Ohio school districts. Teacher pay is still determined via lockstep salary schedules. The pathway to the superintendents’ office still runs through a conventional educator career “ladder.” Local, citizen-led accountability for district performance remains weak due to misguided election laws.

It’s time for a change, and Ohio lawmakers can promote a stronger, more student-centered public school system by making overdue changes in statute. Give district leaders the autonomy and freedom needed to lead, but hold them more accountable for results. Doing so would benefit not only district employees, the vast majority of whom want to excel and accomplish great things, but also the 1.5 million Ohio students who attend district schools.

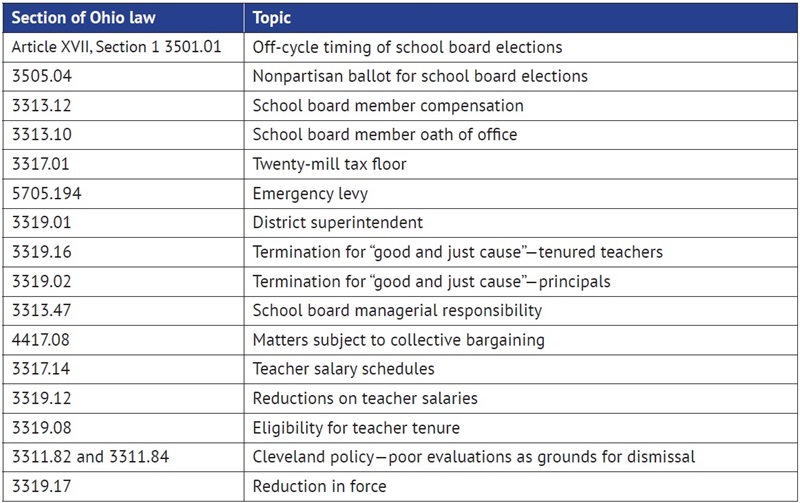

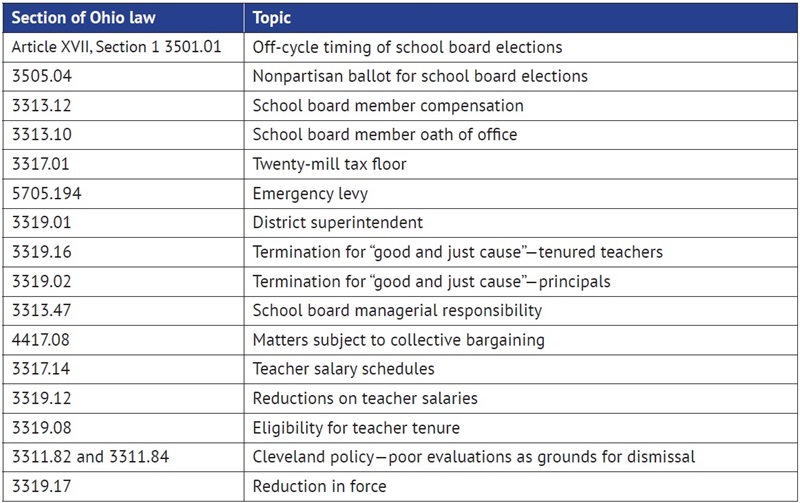

Appendix

Table A1: Ohio statutes referred to in the report

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my Fordham Institute colleagues Michael J. Petrilli, Chester E. Finn, Jr., Chad L. Aldis, and Jessica Poiner for their thoughtful feedback during the drafting process. Jeff Murray assisted with report production and dissemination. Special thanks to Pamela Tatz who copy edited the manuscript and Andy Kittles who created the design.

- Aaron Churchill

Endnotes

[1] The 2000 spending figure is adjusted for inflation to 2021 dollars using the consumer price index.

[2] For instance, school districts receive a certain portion of municipalities’ inside millage—i.e., unvoted property taxes that local municipalities may levy at rates below ten mills.

[3] School-level principals are, of course, another key leadership position. The way they are hired, licensed, and held accountable is a substantial topic that—apart for some discussion on page 9—is saved for another day.

[4] At-will employees in any sector have certain job protections that allow them to appeal terminations based on issues such as discrimination or retaliation. Those protections should certainly apply if superintendents become at-will employees of the board.

[5] Page 85–86 of the Dayton Public Schools’ teachers’ contract outline disciplinary procedures.

[6] Four states—North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia—do not allow collective bargaining for teachers. Wisconsin allows bargaining only on wages.

[7] In addition to the salary schedule, state law also restricts districts’ ability to reduce the annual pay of an individual teacher; pay reductions must be done as part of a system-wide reduction. That language should also be repealed, potentially allowing district leaders to use reduced pay as a disciplinary measure or as a way to retain a teacher who would otherwise be laid off due to budget cuts.

[8] Nontenured teachers are employed under “limited contracts,” with maximum terms of five years and which districts may nonrenew. In cases of nonrenewal, employees would be let go and have less recourse for reinstatement through appeals. In contrast, a “continuing contract” does not expire unless a teacher retires, resigns, or is terminated.

[9] The coursework requirement applies to teachers initially licensed (after 2010) without having earned a master’s degree. This likely applies to the vast majority of teachers who enter with a bachelor’s degree as their highest credential.

[10] In Cleveland, the district has just cause for dismissing a tenured teacher who receives an “ineffective” rating—the lowest mark—for two consecutive years, while principals may be dismissed for “failure for the principal’s building to meet academic performance standards established by the CEO.”

[11] Teachers’ tenure statuses are first compared within their teaching field to make a first round of cuts. Seniority cannot be used as a factor unless a board is comparing teachers of “comparable” evaluations; e.g., two nontenured math teachers with the same (or similar) rating, or two tenured math teachers with the same (or similar) rating, after nontenured personnel have been exhausted.