Ohio leaders need to stand firm on early literacy

If you’ve been paying attention to education headlines this fall, you’ve likely noticed a spate of think pieces and analyses

If you’ve been paying attention to education headlines this fall, you’ve likely noticed a spate of think pieces and analyses

If you’ve been paying attention to education headlines this fall, you’ve likely noticed a spate of think pieces and analyses of NAEP results. NAEP, commonly referred to as the “Nation’s Report Card,” is a series of math and reading assessments administered biennially to a representative sample of fourth and eighth graders from every state. As expected in the wake of school closures and remote learning struggles, Ohio's results revealed significant learning losses. In eighth grade, proficiency rates fell from 38 to 29 percent in math and from 38 to 33 percent in reading. Fourth grade losses were less severe, but proficiency still dropped 1 percentage point in both subjects.

In a previous piece, I discussed how worrisome the eighth grade results are, as these students will soon enter college or the workforce. But teenagers aren’t the only age group we should be concerned about. NAEP declines in fourth grade weren’t as large as those in eighth grade, but fourth graders did lose ground. We don’t yet know what to expect from younger students—including those who started kindergarten in the midst of the pandemic—as neither NAEP nor state tests collect data on students below third grade. And while elementary students may be a long way off from college and career, an uneven start to their academic careers could compound and worsen over time if schools don’t act quickly and efficiently.

Going forward, it will be particularly important to prioritize early literacy. A 2012 report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation indicates that third graders who weren’t proficient in reading were four times as likely to drop out of high school. Longitudinal analyses conducted in Ohio and elsewhere have found similar results. The troubles don’t end once struggling readers reach adulthood, either. For the estimated 16 million Americans who are functionally illiterate, everyday activities like getting a driver’s license, reading news stories online, or voting are far more difficult than they should be.

There is some good news. Recent state test results show a rebound in reading achievement among last year’s third graders, which could indicate that schools are already prioritizing early literacy. Indeed, we have proof that some of Ohio’s largest districts are doing so. A recent piece published by the Akron Beacon Journal offers an in-depth look at how Akron Public Schools is boosting knowledge of the science of reading by requiring teachers who work with the district’s youngest students to undergo an intensive, year-long training known as Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, or LETRS. Columbus City Schools, the state’s largest district, also plans to spend federal Covid relief funding on LETRS training for its teachers. This is great news, as LETRS has been a crucial part of the reading miracle that’s happening in Mississippi.

But good news has limits. In Akron, the early literacy training effort has been met with pushback from some teachers. Dozens of districts—including Akron and Columbus—earned abysmal early literacy scores on recent state report cards, even though they got full credit for the promotional rate dimension of the component thanks to a Covid-related pause on third grade retention. And data show that in most cases, Ohio’s Black and Hispanic students, as well as those from low-income families, fared worse academically than their national peers. Traditionally underserved groups and the tens of thousands of elementary students who attend chronically underperforming districts will face a tough road ahead. And even districts that are on the right track still have a long way to go.

There are policy solutions that could help. Here at Fordham, we recently published a brief that outlines ten ways the state could strengthen its early literacy initiatives. The Ohio Department of Education’s budget priorities aim to boost early literacy in some smart ways, too. But the Akron Beacon Journal’s coverage of literacy training efforts is an important reminder of just how difficult it is to implement big reforms, regardless of how much research exists, how good the changes would be for kids, or how pressing the need currently is. Changing policy is one thing. Changing practice is entirely different.

Ohio has a long history of going all-in on big education policy changes and then backing off when it comes time to implement them. It would be easy, given this history, to throw up our hands and say that early literacy efforts are doomed in the long run. But we can’t afford to do that. Right now, the pandemic defines the educational journey of hundreds of thousands of Ohio youngsters. That’s understandable—of course a once-in-a-generation health crisis and its many impacts are affecting kids—but that doesn’t mean it’s acceptable.

We owe it to Ohio kids and their families to ensure that they can read proficiently. That means when the current early literacy push turns a little less kumbaya, state leaders need to stand strong. Identify evidence-based strategies—especially ones that have worked in other states, like LETRS—and incentivize districts to adopt them. Provide schools with the funds to implement sweeping early literacy interventions and initiatives, and then hold them accountable for the results. Resist political pressure to gut the Third Grade Reading Guarantee’s retention requirement. For the next few years, schools need to do whatever it takes to make sure kids can read. But they can’t—and won’t—unless state lawmakers buck historical trends and stand firm.

In the education world, the last couple months have been awash in news and commentary about sagging student achievement in the wake of the pandemic. The story is no different in Ohio, where students have also lost significant ground compared to pre-pandemic cohorts. Proficiency rates on Ohio’s high school algebra exam, for example, are down from 61 to 49 percent between 2018–19 and 2021–22. For economically disadvantaged students, proficiency rates on this exam decreased from 42 to 30 percent; for Black students, rates slid from 30 to just 19 percent. It’s not just algebra, either. State test results are troubling in other grades and subjects, too, and recently released national assessment data likewise show serious academic decline.

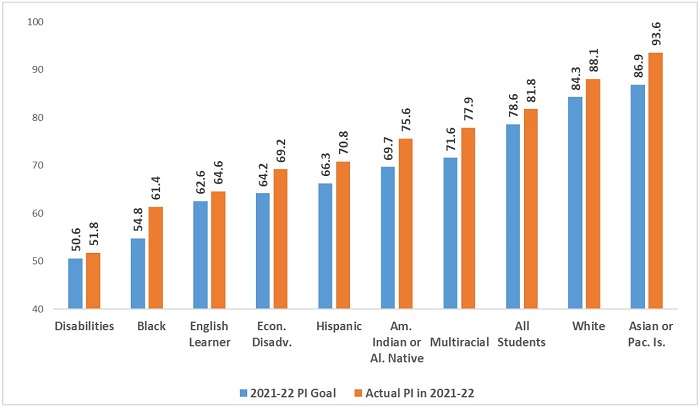

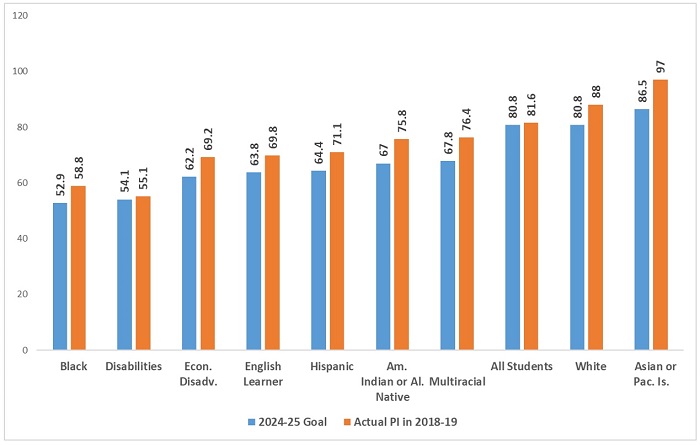

Given these data, it might surprise you to learn that Ohio students crushed the state’s annual achievement goals that are set forth in its federally-required ESSA Plan. The figures below show the performance index scores of the various subgroups whose achievement must be “disaggregated” under federal and state law. The top chart shows that every subgroup topped the state’s achievement goal in English language arts (ELA)—in some cases by fairly wide margins. For example, the ELA performance index score of economically disadvantaged students was 69.2 versus a goal of 64.2. In math, performance against goals was slightly less impressive, but every subgroup, except for students with disabilities, beat its goal.

Figure 1: ELA (top) and math (bottom) performance index scores—actual versus goal—in 2021–22 by subgroup

What gives?

The backstory—and it gets into the weeds—is this. Federal law requires states to establish “ambitious” yearly achievement targets, but in reality, states can set their expectations just about wherever they’d like. Earlier this year, the Ohio Department of Education amended the state’s goals. Recognizing pandemic learning losses, the department slashed the subgroup goals by anywhere from 5 to 26 points, depending on subject and student group. For instance, the department’s ELA goal for economically disadvantaged students was initially an index score of 77.3 for 2021–22, but that number was adjusted to 64.2—a 13-point cut.

Some downshift was probably sensible, but the department went too far in dampening expectations. One issue is that department relied on 2020–21 performance index scores to create a baseline—and those scores were depressed not just from learning loss, but also because of higher numbers of untested students.[1] Fewer students took state exams that year, and untested students count as zeros in the performance index calculations. This artificial “deflation” doesn’t seem to have been accounted for. In fact, economically disadvantaged students could have likely met the state’s 2021–22 goal simply by virtue of greater test participation, not any real academic improvement.

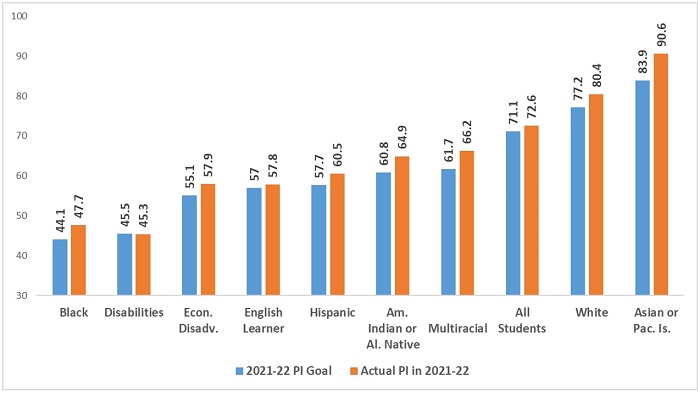

The department might be forgiven for setting extremely modest goals for 2021–22. But what is less pardonable are persistently low expectations for achievement that continue well into the future. Table 1 shows that Ohio doesn’t expect economically disadvantaged students to perform on par with their pre-pandemic counterparts until 2027–28. That’s an inadequate expectation, especially in ELA where the losses have been less severe, rebound has been more evident, and some experts are predicting that full recovery could occur within three years (math may take longer). This goal could be seen as another example of the oft-discussed “soft bigotry of low expectations.”

Table 1: Ohio’s amended ELA performance index goals for economically disadvantaged students

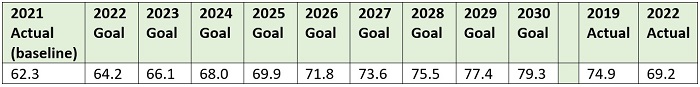

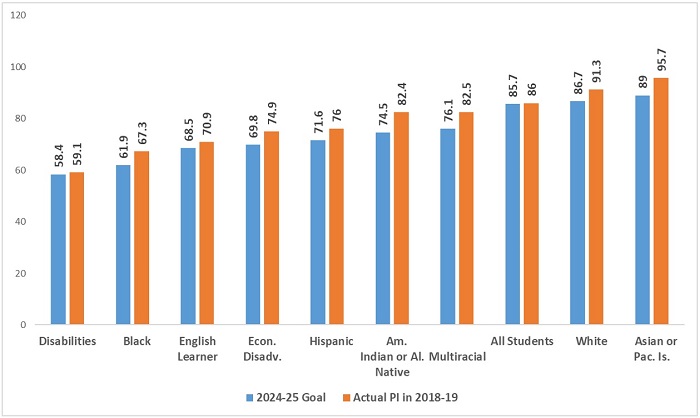

Figure 2 shows that such mediocre goals aren’t limited to economically disadvantaged students, but exist for other groups, as well. These charts display the state’s 2024–25 achievement goals versus the pre-pandemic performance index scores of each subgroup. There is no instance in which the state expects a subgroup to meet pre-pandemic achievement levels by this year, and for some subgroups, the goal is quite a bit lower. For example, by 2024–25, Black students are expected to post an ELA index score of only 61.9, even though their pre-pandemic peers scored 67.3.

Figure 2: ELA (top) and math (bottom) performance index scores—actual in 2018–19 versus 2024–25 goal—by subgroup

Setting low achievement goals has implications for both policy and practice. For one, these goals are used in Ohio’s report card system, as schools’ Gap Closing ratings are based in part on whether subgroups achieve these targets. One consequence of softening targets in 2021–22 was that most schools received rosy Gap Closing ratings—more than 60 percent received four or five stars—even at a time when students were struggling with serious learning loss. Such ratings could be misleading the public into thinking that schools are narrowing gaps when, in fact, they are widening.

Perhaps more important is what these goals communicate to schools. They seem to say “it’s OK for learning losses to persist well into the second half of this decade.” That message is exactly the wrong one for state leaders to send Ohio schools. Instead, the state’s achievement goals should be incentivizing schools to go above and beyond the status quo on behalf of students who, by no fault of their own, lost significant ground during the pandemic.

In a recent piece, my Fordham colleagues Amber Northern and David Griffith write, “If we’re serious about getting our students back on track, we must be even more serious about getting our expectations for them back on track.” They are right. We do need to get back to having high expectations for all Ohio students.

The department should scrap these “pandemic-adjusted” goals and start fresh, with an eye towards full recovery by 2024–25. Some may think that’s too ambitious. Some might worry about dinging schools’ ratings. Perhaps Ohio’s amended goals are already locked in with the feds (it’s not clear if they’ve been approved). If that’s the case, fine. Let’s create a set of “real” achievement goals that Ohio’s leaders and schools can get behind. But fears and bureaucracy shouldn’t stop us from setting aspirational targets that motivate schools to achieve something big for Ohio students.

[1] 6.4 percent of Ohio students were untested in 2020–21 (compared to 2.0 percent in 2021–22). Had the untested students taken an assessment, they would have generated a minimum number of points towards the index score.

Starting a teaching career is no easy feat. There are students and staff to get to know, curricula to learn, school routines and expectations to get acquainted with, and a host of other challenges. For many novice teachers, the first few years can be overwhelming enough to push them out of the profession entirely.

To help new teachers get off on the right foot—and to prevent too many of them from leaving the field due to a lack of support—Ohio established the Resident Educator Program (REP). A state-level initiative that began in 2011, teachers are required to complete REP before they can become eligible for a professional teaching license. The program is best understood as having two parts:

It’s important to note that the ideas behind REP and RESA are evidence-based. The Institute of Education Sciences found that novice teachers who are assigned a first-year mentor are more likely to stay in the classroom. A review of the research on the impact of induction and mentoring programs found that, in most studies, beginning teachers who participated in some kind of induction program had higher satisfaction, commitment, or retention; performed better at various aspects of teaching, such as developing lesson plans; and that their students demonstrated higher gains on academic achievement tests. In that same vein, a 2017 study shows that induction programs for new teachers can have overall positive effects on student achievement in math and English language arts.

Given the research, it’s no surprise that the Ohio Department of Education says REP was designed to “improve teacher retention, enhance teacher quality, and result in improved student achievement.” RESA, meanwhile, was intended to function as a final stamp of approval from the state; a teacher version of the exam that medical residents must pass before they can practice unsupervised. Novice teachers who demonstrate their skills by passing RESA can continue teaching in Ohio classrooms, but those who fail to pass after three attempts are barred from a professional license and must find themselves a new career.

It’s also important to acknowledge, though, that REP and RESA themselves have not been the subject of rigorous, empirical study. As far as I can tell, there is no publicly and readily available evidence that Ohio teachers who perform well on RESA produce better student outcomes than those who don’t perform as well. Similarly, there is no evidence that REP or its associated supports have increased teacher quality (as measured by student outcomes or teacher evaluation scores) or decreased the likelihood of attrition. The closest thing we seem to have is a very limited 2016 study from the University of Findlay that examines “open-ended commentary” from teachers regarding REP. Most of the 245 teachers (which doesn’t even amount to 1 percent of Ohio’s teacher workforce at the time) who were surveyed didn’t believe that the program improved their ability to meet the Ohio Standards for the Teaching Profession.

The upshot? After more than a decade of implementation, it’s unclear whether REP and RESA are actually doing what they were designed to do. The ideas are research-based. The teachers union and a former state superintendent have voiced support for the program. But there are also teachers who claim it’s nothing more than a “cumbersome process” that adds to their workload and increases their stress levels.

Furthermore, the absence of proof that the program is effective—and the apparent disagreement among practitioners about whether it’s worth it—has led to plenty of legislative tinkering. The General Assembly went so far as eliminating the program in the 2017 budget. A last-minute veto from then-Governor Kasich saved it, and RESA underwent a significant overhaul soon after. Last year, the legislature knocked REP down from a four-year program to a two-year one (a change that won’t go into effect until next year). A bill that was passed by the House this summer aims to make additional changes, including allowing resident educators to take RESA as many times as they want.

The only way to avoid several more years of controversy—and to prevent well-meaning lawmakers from watering down the program or throwing the baby out with the bath water—is to gather as much information as possible about its effectiveness. From a quantitative standpoint, the Ohio Department of Education or independent researchers should dig into the data to determine whether high RESA scores are correlated with higher value-added scores or better teacher evaluations. We also need more systematic and current information about how new teachers perceive and experience the program. To accomplish this, the state should:

The bottom line is that effective and well-implemented induction and mentoring programs benefit both teachers and students. Ohio has had a seemingly well-crafted one on the books for more than a decade, but we have no idea whether it’s effective. Rather than continuing to allow legislative tinkering that may or may not be improving it, state leaders should make sure that we have the information and data needed to assess the program and, if necessary, improve it.

In 2010, a group of researchers from the World Bank and the Central Bank of Brazil began to study the efficacy of a financial education program delivered to high schoolers in Brazil that aimed to help young people make good decisions around saving, borrowing, and credit usage. Their first report, in 2016, looked at short-term findings of the randomized control study and found decidedly mixed outcomes. A newly-published follow up looks at the students’ financial situations years later and finds that many of its young subjects have become more money wise in the longer run.

The experiment was conducted in 2010 and 2011 and included 25,000 students in 892 schools across six Brazilian states. Half the schools were randomly selected to receive teacher training and financial education textbooks. The treatment was integrated into the classroom curricula of math, science, history, and Portuguese during students’ last two years of high school. Control group schools did not receive the new training or materials, nor was any other formal financial education provided.

In their earlier analysis, just after high school graduation, researchers found that the program led to increased financial knowledge among treatment group students, as well as positive effects on attitudes toward savings, self-reported saving up for purchases, money management, and budgeting. On the other hand, treatment students reported a significantly greater use of expensive financial products such as credit cards, as well as greater likelihood of being behind on credit repayments than their control group peers. These differences were visible even before they had left high school. The research team speculated at the time that the curricular materials raised the profile of these risky products but may have erred by not actively discouraging their use.

The data in the new report come from administrative records on a subsample of nearly 16,000 individuals from the original experiment, covering nine years after their high school graduation. Long-run financial outcomes were tracked using data on bank account ownership (but not account balances), use of various credit products, as well as information on formal employment status and microenterprise ownership. Data span from students’ high school graduation in 2011 to February 2020, just before the Covid-19 pandemic hit Brazil. Slightly more than half of the subsample were in the original control group. The subsample contained significantly more females than did the full sample; otherwise the subsample’s treatment and control groups were statistically similar to the originals.

First the analysts looked at the same outcomes as in the previous study. The financial education program had no long-term effect on bank account ownership (although a commendable 85 percent of students in the full sample had bank accounts in 2020). Treatment students, however, used fewer expensive credit products in the long-term. They were 1.4 percentage points less likely to have credit card debt and 0.9 percentage points less likely to use overdrafts, compared to 23 percent of control students with credit card debt and 11 percent of control students with overdrafts at nine years post-graduation. The program also appeared to lead to lower the likelihood of having loans with repayment delays by about 0.9 percentage points, compared to 15 percent of control students with repayment delays.

There is no way to determine the mechanisms behind these long-term improvements using this methodology. But the researchers’ speculations seem reasonable: Maybe students “experimented” with expensive credit when young and then realized that this was not a sound financial decision, or perhaps they realized that expensive credit was untenable when larger, more expensive, “grown up” purchases were contemplated. The phrase “live and learn” comes to mind.

As to additional outcomes, treatment students were 3.69 percentage points more likely to own a formal microenterprise in 2020 than were control students and were 1.2 percentage points less likely to hold a job with a written contract, suggesting that the program encouraged a focus on owning their own business rather than being employees beholden to a boss or company. The researchers speculate that these effects stem from program modules on work and entrepreneurship whose impacts would only be seen later in students’ lives.

It’s certainly possible that the researchers are giving a bit more credit to a high school financial literacy program than they probably should. A lot happened in Brazil—and in the world economy—in those nine years, including a two-year-long recession. There is no way of knowing whether such upheavals impacted individuals differently, especially with so many students from the original study unaccounted for, nor what additional financial education they may have received in the interim, either formally or via the school of hard knocks. But perhaps that is the point here: Arming students with financial knowledge before they head out into the working world may help many of them navigate some of the difficult ups and downs of adulthood, no matter how treacherous those may be.

SOURCE: Miriam Bruhn, Gabriel Garber, Sérgio Mikio Koyama, and Bilal Zia, “The long-term impact of high school financial education,” World Bank Group (October 2022).

What parents are looking for in an ideal school choice scenario is often very different from what they settle for in the real world. Cost, distance, academic quality, safety, extracurricular options, and a host of other factors are all at play, meaning trade-offs are unavoidable. Recently-published research findings try to capture the matrix of compromises being made.

Data come from Kansas City, Missouri, from fall 2016 to spring 2017. School options were widespread in the city, including intradistrict opt-in among all twenty-six of Kansas City Public Schools’ (KCPS) general education buildings and nine magnet schools, along with twenty public charter schools and twenty-four private schools. At the time of the study, more than 8,500 students (23 percent of all K–12 students) attended private schools, over 6,500 students (18 percent of the total) attended charters, and over 4,100 (11 percent) attended magnets. Around 70 percent of the remaining students attending general education KCPS buildings opted for a school outside their neighborhood assignment zone. Aiding parents in their choices: a single application for any KCPS building, including magnets, and a second single application that covered nearly all of the city’s charters.

The Kansas City Area Education Research Consortium recruited parents through multiple avenues in 2016 and 2017 to answer survey questions regarding school preferences. The sample comprised 436 individuals, proportionally representing district attendance zones, racial makeup of the population, and socioeconomic distribution around the city. Approximately 33 percent of respondents had a college degree. While no breakdown exists for how many students attended which school type, all types were represented.

Respondents were first asked to rate, on a scale of one to five, how important each of nineteen school attributes was to them in choosing a school for their oldest child. Attributes included academic performance, afterschool programs, teacher and student diversity, curriculum, facilities, leadership, parent involvement, and safety. Most importantly, respondents were asked to rate their preferences “in the context of an ideal world where they were not bound by social, economic, or logistical constraints and concerns.” They were then asked to choose their top three based on their current real-world circumstances and with “personal constraints,” as well as any “systemic obstacles” they have encountered in mind. Finally, they were asked to rate on a scale from one to five how satisfied they were with their child’s school, and, on a reverse scale, to what extent their child’s school “[fell] short in things that would otherwise make a difference” in their education.

So how far was the ideal from the reality? It depended on the family. No one got everything they wanted because everyone’s ideal ratings put almost every school feature at the top of the list. While teacher quality was highest and social/medical services lowest, there were less than 1.5 ratings points separating them (4.82 out of five vs. 3.37) and all seventeen other features were crammed in between. Parents who were White, had any education level above high school, and earned over $50,000 per year were more likely to rank their child’s school very highly on their top three attributes than were their peers, marking what the researchers deem a state of lowest “preference compromise.” That is, their children were more likely to attend schools in the real world that ranked highly on the attributes that mattered most to them in an ideal condition. Parents outside those demographic categories were more likely to report attending schools where their highest-rated attributes are not present or present at a lower level than their peers, indicating a less-than-ideal choice. Hispanic parents were most likely to report compromising on their highest-rated attributes, with Black parents close behind. Parental satisfaction scores track with level of compromise—the bigger the gap between ideal attributes and real experience, the lower the reported satisfaction level. The researchers thus conclude that these families are least-well served by school choice in Kansas City, but that leap owes more to the ideal than to the real.

On the upside here, all families’ preferences were considered equal in the analyis, with no leeway to consider that parents with lower education or income levels might lack knowledge of important school attributes or available options. This is extremely positive and a better approach than many previous such studies. On the downside, the methodology assumes that all parents have already chosen—and are reporting their satisfaction with—their best possible option. This is nominally true, but the universe of options for a family with one working parent and two cars is likely to be different—and much larger in the real world—than for a family with two working parents and a single vehicle, even if their incomes are the same and even if they live in the same zip code. Given modern residential patterns and school zone boundaries’ correlation with historic redlining efforts, the gap beween the ideal and the real is already baked into school choice infrastructure in many cities—especially for familes with fewer resources. It is true that lower-income families or Hispanic families have less access to school choice, but the researchers’ conclusion that such a fact renders school choice problematic does not logically follow.

While not giving more families a free ticket into the ideal school of their dreams, KC did offer a fairly robust choice environment in 2017. The sheer number of students attending non-assigned district schools at the time is evidence enough of that. A majority of parents—from all walks of life—likely found for their children a choice they liked better than they would if they had been forced to send their child to their zoned school with no alternatives. And that’s a win.

SOURCE: Argun Saatcioglu and Anthony R. Snethen, “Preference Compromise and Parent Satisfaction With Schools in Choice Markets: Evidence From Kansas City, Missouri,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (October 2022).

NOTE: Today, the state board of education heard public comment on a pending resolution which would call for the elimination of the retention provision of Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee. Below are the written remarks given by Chad L. Aldis, Fordham’s vice president for Ohio policy at that meeting.

Thank you, President Maguire, Vice President Manchester, and State Board members for the opportunity to provide public comment on the resolution calling for the elimination of the retention requirement for third graders who cannot meet the state’s promotion threshold.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the vice president for Ohio policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

Reading is absolutely essential for functioning in today’s society. Job applications, financial documents, and instruction manuals all require basic literacy. And all of our lives are greatly enriched when we can effortlessly read novels, magazines, and the daily papers. Unfortunately, even today, roughly 43 million American adults—about one in five—have poor reading skills. Of those, 16 million are functionally illiterate.

Giving children foundational reading skills, so they can be strong, lifelong readers, is job number one for elementary schools. Understanding this, Ohio passed the Third Grade Reading Guarantee in 2012. The law’s aim is to ensure that all children read fluently by the end of third grade—often considered the point when students transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.”

The Guarantee takes a multi-faceted approach. It calls for annual diagnostic testing in grades K-3 to screen for reading deficiencies and requires reading improvement plans and parental notification for any child struggling to read. Importantly, it also requires schools to hold back third graders who do not meet state reading standards and to provide them with additional time and supports.

I urge the State Board to reconsider its recommendation to eliminate the guarantee’s retention requirement.

Why retention?

The goal of retention is to slow the grade-promotion process and give struggling readers more time and supports. When students are rushed through without the knowledge and skills needed for the next step, they pay the price later in life. As they become older, many of them will decide that school is not worth the frustration and make the decision to drop out.

An influential national study from the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that third graders who did not read proficiently were four times more likely to drop out of high school. A longitudinal analysis using Ohio data on third graders found strikingly similar results. The consequences of dropping out are well-documented: higher rates of unemployment, lower lifetime wages, and an increased likelihood of being involved in the criminal justice system.

Seeing data such as these, almost everyone agrees today that early interventions are critical to getting children on-track before it’s too late.

Some believe that schools will retain children without a state requirement. Anything’s possible, but data prior to the Reading Guarantee makes clear that retention was exceedingly rare in Ohio. From 2000 to 2010, schools retained less than 1.5 percent of third graders. Retention has become more common under the guarantee, as about 5 percent of third graders were held back in 2018-19.

In 2021-22, however, Ohio temporarily waived the promotion requirements and we saw a return to social promotion. Schools promoted virtually every third grader to fourth grade, whether they could read fluently or not; in fact, 100 percent of third graders were promoted in 469 out of 605 districts. At the same time, we also know that 20 percent of Ohio’s third graders have serious reading difficulties, having scored “limited”—the lowest achievement level on state exams. Students at this level earned less than 11 out of 40 possible points on their third grade ELA exam.

Make no mistake, if the legislature follows your advice and removes the retention requirement, Ohio will in all likelihood revert to “social promotion.” Students will be moved to the next grade even if they cannot read proficiently and are unprepared for the more difficult material that comes next. There’ll be relief in the short-run but the price in the long-term will be significant.

Data and research

Shifting gears, I’d like to briefly address two claims that regularly come up in Ohio when the topic is retention.

First, some have claimed—based on research studies—that holding back students can have adverse impacts. There is some debate in academic circles about how to assess the impacts of retention. Doing a gold-standard “experiment” with a proper control group is not possible in this situation, so scholars rely on statistical methods that help make apples-to-apples comparisons between similar children. But unless researchers use very careful methods, the results don’t give us much insight.

Arguably, the best available evidence on third-grade retention—as opposed to retention generally—comes from Florida, which has a similar policy to Ohio’s reading guarantee. That analysis, which compared extremely similar students on both sides of the state’s retention threshold, found increased achievement for retained third graders on math and reading exams in the years after being held back. It also found that retained third graders were less likely to need remedial high school coursework and posted higher GPAs. The analysis found no effect, either positively or negatively, on graduation.

If you would like to review this research for yourself, an essay on the findings by Harvard University’s Martin West, who led the Florida study, was published by the Brookings Institution in 2012. The longer, academic report was published by the National Bureau of Economic Research and in the Journal of Public Economics in 2017.

The second claim, particular to Ohio, is that the reading guarantee isn’t producing the improvements we’d like to see. The basis is a paper from The Ohio State University’s Crane Center that notes flat fourth grade reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress from 2013-17. NAEP does offer a useful high-level overview of achievement, but raw trend data are not causal evidence about the impact of the third grade reading guarantee—or any other particular program or policy. The patterns could be related to any number of factors that affect student performance, whether economic conditions, demographic shifts, school funding levels, and much more. Without any statistical controls, it’s impossible to isolate the effect of the reading guarantee.

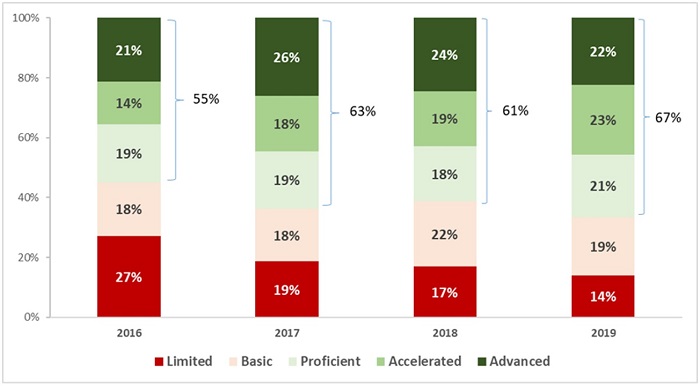

Of course, NAEP isn’t the only yardstick. It’s also worth considering what state testing data show. The chart below shows third grade ELA scores in Ohio. We see an uptick in proficiency rates—from 55 percent in 2015-16 to 67 percent in 2018-19. Also noteworthy, given the guarantee’s focus on struggling readers, is the substantial decline in students scoring at the lowest achievement level. Twenty-seven percent of Ohio third graders performed at the limited level in 2015-16, while roughly half that percentage did so in 2018-19.

I’d like to pause and emphasize this point. From 2016 to 2019, the percent of students reading at the lowest level was cut in half. Much of the data in the resolution focuses on proficiency, and I understand the inclination to do that. Ohio’s policy has been focused on getting students from “limited” into the middle of “basic” where the promotion score has been. And that is exactly what Ohio teachers and students appear to have done.

Ohio’s third grade ELA scores, 2015-16 to 2018-19

Much like NAEP trends, this shouldn’t be construed as causal evidence. But the improvements on third grade state exams should be weighed heavily in any analysis on whether the guarantee is improving literacy across Ohio.

Right now, no rigorous evaluation of Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee and the retention requirement has been conducted; however, the structure of Ohio’s law and the strong data system in place lends itself to a high quality research design. We encourage the State Board to take a step back and request that the department conduct a study on this issue before recommending that the retention requirement be eliminated.

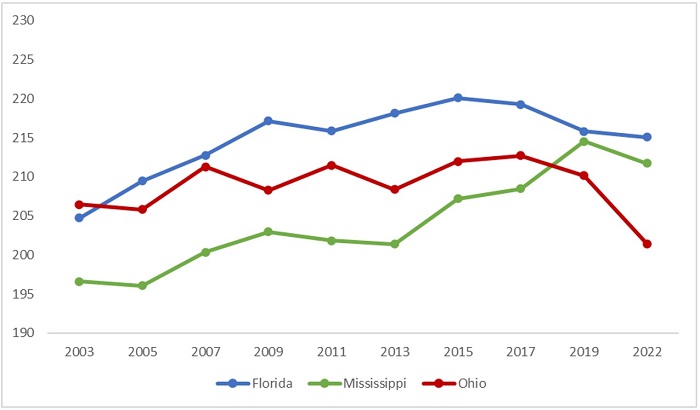

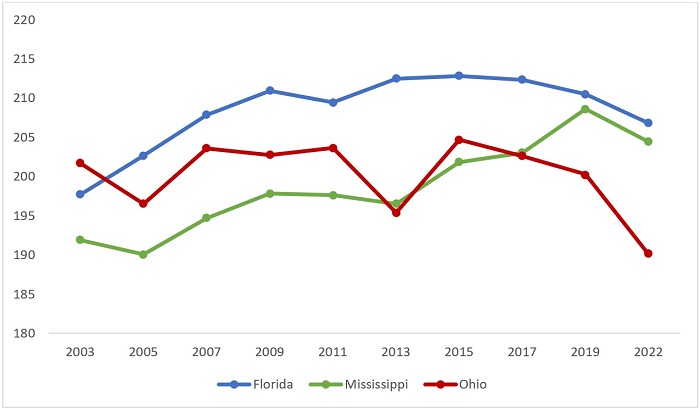

As I noted earlier, NAEP data is useful but not causal. If your inclination is to stick with NAEP though, you should look closely at what’s happened in Florida and Mississippi. Both states rigorously implemented comprehensive early literacy policies, including a third grade retention policy, and have enjoyed tremendous success.

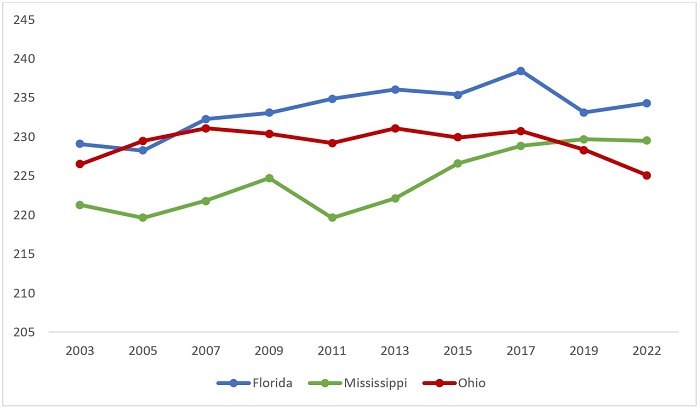

NAEP scores in fourth grade reading, students eligible for free and reduced price lunch

NAEP scores in fourth grade reading, Black students

NAEP scores in fourth grade reading, White students

In 2003, economically disadvantaged and Black students in Florida had lower NAEP fourth grade reading scores than their peers in Ohio. By 2022, both student group performed for than 15 points higher than similar students in Ohio. It’s important to note that 10 points is generally seen as a grade level. Mississippi’s success is even more dramatic. They started reforming policies in 2013—a year after Ohio—and their progress has been nothing short of remarkable. As you can see from the NAEP data above, white, Black, and economically disadvantaged students in the Magnolia State closed a sizable gap and now outperform their peers in Ohio.

Ohio students simply aren’t keeping pace in reading with students from Mississippi and Florida. If this was college football, we’d be firing people. But, it’s not. It’s more important.

Ten years ago, Ohio lawmakers decided it would be better to intervene early than have students suffer the consequences later in life. The logic made sense then, and we believe that it’s still true today. Of course, retention—like any policy—isn’t a silver bullet. It must be paired with effective supports, and students need to continue receiving solid instruction in middle and high school. What the policy does, however, is slow the promotional train and give struggling readers more attention and opportunity to catch up.

As data from Florida and Mississippi suggest, it can be done. Their teachers and students aren’t somehow better than ours. What they have had is unflinching state leadership. Ohio students deserve that same commitment. Now is the time to help all students learn to read—not the time to back down.

Thank you for the opportunity to offer public comment, and I look forward to any questions that you may have.