NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

Charter schools are publicly funded but independently operated schools that serve students in grades K–12. Despite receiving far less funding than traditional public schools, they’ve significantly improved the educational options for Ohio families, many of whom lack the financial means to leave ineffective district schools. Indeed, on average, brick-and-mortar charters’ educational benefits are substantial—particularly for students from low-income households.

That’s not my opinion—it’s based on objective data analysis. Using rigorous statistical methods, my 2020 analysis of Ohio’s charter schools indicated that students attending brick-and-mortar charters between 2016 and 2019 were way better off than they would have been had they attended district schools. They learned more each year, were less likely to be absent, and were less likely to be suspended—all because they attended a charter school instead of a nearby district school. These effects were large, implying that students would receive the equivalent of an extra year’s worth of learning (180 days!) if they attended charter schools instead of their district schools from grade four to grade eight. The gains were largest for Ohio’s Black and Hispanic students.

Unfortunately, a false narrative about Ohio’s charter schools can emerge when one presents the data the wrong way. Recently, Education Week reported on a new study by CREDO, based on 2015–2019 data across thirty-one states, which found that charter schools across the nation generally outperformed traditional public schools. But the study also stated that Ohio charter students lost ground in math compared to otherwise similar students attending nearby district schools. Even worse, the article stated “Ohio charter schools saw the largest drop” in mathematics achievement (relative to nearby district schools) among the states in the study. Subsequently, The Center Square, an Ohio statehouse news outlet, used those results to build a case against funding school choice in Ohio.

How on earth could CREDO come to that conclusion? After all, like my study, CREDO uses rigorous statistical methods that compare the learning rates of charter students to those of similar students in the same district (students with the same baseline achievement, same demographic characteristics, similar household income, and so on). We also use the same dataset. Did one of us make some sort of coding error when running our statistical models?

There are two reasons that CREDO’s report makes it look as if Ohio’s charters are doing poorly relative to charters in other states. First, while they include students attending brick-and-mortar charter schools in their analysis, they combine those brick-and-mortar charter students with students who learned remotely via online schools, as well as those who attended specialized schools (such as “dropout-recovery” schools for at-risk kids and schools that serve almost exclusively students with disabilities). Unfortunately, lumping all these schools together obscures the strong results of Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools. Second, their estimates are based on averaging effects across five years (2015–2019) and do not capture the substantial improvement in Ohio’s charter sector during that time span—following Ohio’s major regulatory reforms that greatly increased the accountability for charter schools. I address each of these important problems in turn.

Online charters

The pandemic made clear to everyone—particularly parents and teachers—that online schooling is tough. Prior research has long shown that students tend to learn far less when schooling occurs online—particularly those who lack the proper supports at home. Parents often have very good reasons to enroll their kids in online schools. Perhaps their kids were bullied. Or perhaps the local district school is too far away or does not offer the curriculum they need. But the tradeoff is that most students learn much less online, particularly in mathematics. And because all online schools were technically “charter schools” during their period of study, CREDO’s analysis must compare the achievement of students in online charter schools to the achievement of students attending district schools in person. When doing so, they find that online charter students nationally lose an equivalent of fifty-eight days per year of learning in reading and 124 days in math. States with relatively large enrollments of online students would, therefore, appear worse when they are included in such an analysis.

And that’s exactly what CREDO found. For example, of the nine states they list as top performers for posting superior gains in math and reading, five don’t allow online charter schools (Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Tennessee). Of the two states where charters have negative impacts in math—Ohio and South Carolina—both have by far the highest share of online enrollments (more than double the average rate of online schooling across all states in CREDO’s sample). In addition to the 25 percent of Ohio charter students attending online schools and the approximately 60 percent attending brick-and-mortar schools providing a general education, Ohio’s remaining 15 percent of charter students in 2019 attended a school that caters primarily to students with special needs. Again, in CREDO’s study, these charter schools are compared to regular district schools, but it’s not quite clear whether that’s an appropriate comparison.

There is no doubt that comparing Ohio (with lots of online charter students) to, say, Massachusetts (with no online charter students) creates a false impression about the relative effectiveness of their charter sectors. And Dr. Raymond, CREDO’s director, knows it. The Education Week article states “Data from the online schools drag down the average performance for students in all charter schools, Raymond said.” So why combine students across sectors? Why not create a more apples-to-apples comparison across states? Why not compare Massachusetts brick-and-mortar schools to Ohio’s brick-and-mortar schools, for example? That would provide clearer insight into how the schools that most families consider an option for their children perform from state to state. As noted above, Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charters would likely stack up well against other locales.

Annual improvements

Even if you agree with CREDO that online and in-person schools should be combined,[1] CREDO’s analysis is still misleading. That is because CREDO’s analysis generates estimates based on data pooled across 2015–2019. Any improvements in a state’s charter sector that occurred during that span would be obscured—weighed down by the lower quality of the sector in early years.

That’s particularly problematic for Ohio. In 2015, the Ohio General Assembly enacted a rigorous set of reforms that greatly increased accountability for charter school authorizers (called “sponsors” in Ohio); included provisions that sought to improve online charter schools and the financial management of all charters; and required more transparency around the practices of charter operators—the organizations that many Ohio charter school boards contract with to run their schools.

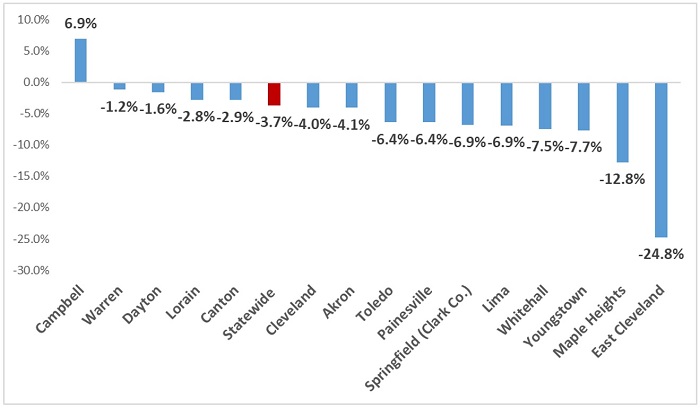

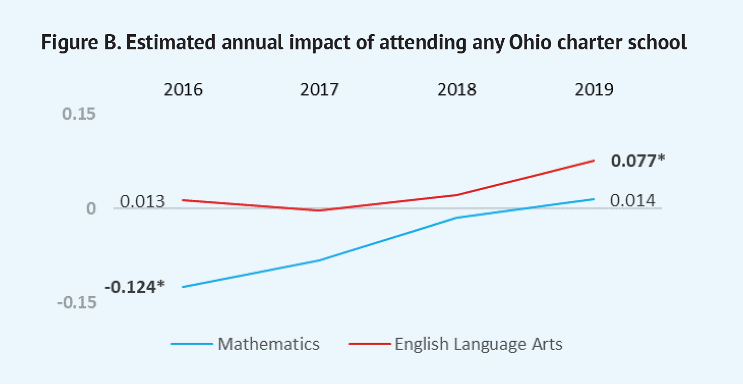

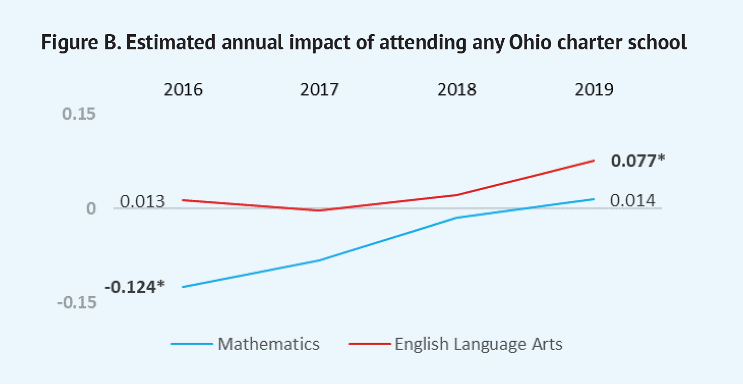

Ohio arguably went from having one of the least-regulated charter sectors in the nation to having a far more accountable sector. From 2015 to 2019, dozens of low-performing schools and operators were shut down, and the better ones remained, leading to a dramatically improved overall charter sector. The figure below—drawn from my 2020 report—documents this improvement in annual learning among all Ohio charter students (both brick-and-mortar and online schools).

The figure indicates that, in 2016, charter students learned far less math annually than similar students in their district schools (0.124 standard deviations less). That effect is as if students had received seventy-two fewer days of instruction annually than if they had attended their local district school. Averaging estimates across 2016–2019, the charter school disadvantage is equivalent to about thirty-two fewer days’ worth of learning in mathematics annually. That is just slightly different than the thirty-eight fewer days of annual learning that CREDO estimated across 2015–2019.

Yet we care much more about 2019 than 2015. In 2019—across all charter students (including the online and special education students)—students in Ohio’s charter schools had, on average, the equivalent of forty-five extra days’ worth of learning in English language arts (a 0.077 standard-deviation gain). And, though not statistically significant, it appears they also gained eight extra days’ worth of learning in mathematics. Those results are masked when the data are combined across multiple years.

There is much to admire about CREDO’s latest report. The statistical methods are rigorous; it provides a wealth of information (including estimates of the quality of specific charter management organizations and school networks); and the general take-home point, that charters across the nation are improving and that they provide an important alternative to traditional district schools, is welcome. I also don’t doubt that Dr. Raymond’s inclusion of both online and in-person students comes from a good place—a concern that we should ensure that charters serve all students well. But the lack of attention to Ohio’s context is careless and needlessly perpetuates a false narrative. Upon closer inspection, we see that Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charters are strong performers—and getting better.