The social and emotional damage of socially promoting struggling readers

Over the last few weeks, debates about early literacy have dominated headlines in Ohio.

Over the last few weeks, debates about early literacy have dominated headlines in Ohio.

Over the last few weeks, debates about early literacy have dominated headlines in Ohio. Much of the conversation has revolved around the state budget, as Governor DeWine included in his recommendations a bold plan to improve reading achievement in Ohio by requiring schools to use high-quality curricula and instructional materials aligned with the science of reading.

Despite the renewed focus on early literacy, some lawmakers have proposed dismantling the decades-old retention requirement of Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee, which requires schools to hold back students who, based on state assessments or state-approved alternative exams, aren’t meeting reading standards by the end of third grade. Schools must provide these students with intensive interventions such as summer reading programs or tutoring. But House Bill 117 aims to abandon the requirement, and House lawmakers proposed a similar provision in their recently released version of the budget.

This is the wrong move, akin to your optometrist refusing to provide the glasses prescription she knows you need and expecting you to make do with blurry vision instead. For starters, there’s a considerable amount of evidence showing that, when combined with intensive supports, retention has a positive impact on students’ short-term and long-term success. In several other states—like Mississippi, which has been hailed as a learning miracle—retention has been a crucial part of its widespread reading improvement.

But for many critics, these positive academic impacts take a backseat to the harm that they believe retention can have on a student’s social and emotional wellbeing. These aren’t concerns to take lightly. The mental health of students matters, especially in the wake of a pandemic that not only upended the stability that kids often count on from school, but also robbed them of vitally important experiences both inside and outside the classroom. Now, more than ever, it’s important for teachers, parents, advocates, and policymakers to be mindful of how policy and practice impacts the mental health and wellbeing of students.

The problem, though, is that by identifying retention as the only potential source of social and emotional harm, critics completely overlook the significant impact that poor reading skills and illiteracy can have on students who are socially promoted. In fact, nearly every social and emotional impact cited by opponents as a reason to eliminate retention could also be applied to students who fail to achieve reading proficiency by the end of third grade.

Students who are socially promoted but continue to struggle with reading can get made fun of by other children—especially in the older grades, when reading becomes fundamental and a lack of fluency and comprehension becomes glaringly obvious. Struggling readers often experience frustration or boredom in class because they can’t keep up with their peers, which could lead to an increase in disruptive behavior and school discipline incidents. They can also suffer from low self-esteem because they struggle academically, and may feel ashamed that they need remediation. Without a caring adult to notice what’s going on and offer support and encouragement, they may even internalize their academic difficulty as an inflexible marker of their worth rather than a temporary obstacle that can be overcome with the right help.

I know all this from personal experience because, as a high school English teacher, I saw the negative impacts of social promotion every day. Many of my most persistently disruptive students acted out not because they were bad kids—they definitely weren’t—but because they struggled to read and write and keep up with their peers, and were embarrassed and frustrated as a result. On the flip side, some of my best-behaved students were nearly half a dozen grade levels behind where they should have been. They worked hard and participated and followed every rule to the letter, but because they’d been passed on by so many teachers before me, their poor reading skills made it extremely difficult for them to master the content of a high school English course.

On more than one occasion, I stepped in to stop one student from bullying another over their limited reading skills. There were dozens of students who, because they couldn’t read proficiently, were struggling in all their classes. These students needed intensive reading intervention, but my high school—like most high schools—wasn’t equipped or prepared to teach such basic fundamentals. The further away my students got from elementary school, the less likely they were to get the reading intervention and support they needed from teachers and staff who specialized in early literacy.

One instance, specifically, sticks out in my mind. I remember standing in the hallway outside of my ninth-grade classroom during my first year teaching. The mother of one of my students—we’ll call him Sam—had stopped by with her son to ask how he was doing in my class. We’d just finished diagnostic testing, so I told her the truth: Despite being in ninth grade, Sam had the reading skills of a fifth grader. He was certainly capable of catching up, and I was going to do everything in my power to make sure he did, but it was going to be an uphill climb. I’ll never forget the look on her face or how she cried when she told me that no one had ever told her that her son struggled to read proficiently. I’ll never forget that she asked me how it was possible for her son to be in ninth grade if he couldn’t read at a ninth grade level. I had no answer.

Sam was a great kid. He paid attention and worked hard, his mother was involved, and I worked my butt off that year to give him the education he deserved. But by the time he walked through the door of my classroom for his first day of ninth grade, Sam was already six years beyond the third grade make-or-break reading benchmark. He refused to read aloud in my class (and I never forced him to) because he knew other students would make fun of the way he stumbled over his words. His reading struggles had a huge impact on his academic outcomes, both in my English class and in his other courses. But they would impact his life outside school, too. The written knowledge test he would have to pass to earn a driver’s license, the ballot measures and candidate information he would need to read to exercise his right to vote, the daily news he needed to grasp to understand the world—these were basic tasks that were severely hindered by his lack of reading proficiency.

Sam knew all of this. He knew he couldn’t read very well, and he knew it made him different than some of his classmates. He knew how much more difficult his life would be—because it already was. For Sam—and for millions of other kids—the social and emotional impacts of illiteracy are massive and far-reaching, even when those students are “protected” from retention.

Pretending that moving struggling students onto the next grade saves them from social and emotional harm isn’t just wrong, it’s irresponsible. We owe it to students to give them the intervention and support they need to become proficient readers before they go on to middle and high school. Advocates and policymakers need to recognize that because illiteracy has such enormous social and emotional impacts, we should be intervening as early as possible. Retention, coupled with rigorous intervention, gives students a chance to catch up with their peers and avoid a lifetime of struggle. Social promotion doesn’t offer that—and claiming that it does is educational malpractice.

Led by Governor DeWine, the science of reading movement is taking off in the Buckeye State. While the push is new in Ohio, the reading science isn’t. Rather, it is a return to tried and true methods of teaching children to read through a focus on the five pillars of effective literacy instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. At the same time, state leaders are working to root out ineffective “whole language” and “balanced literacy” approaches that have permeated too many Ohio classrooms.

To add fuel to this movement, the governor included significant literacy reforms in his budget proposals. Among them are a statewide requirement that Ohio schools adopt high-quality literacy curricula aligned with the science of reading, and tens of millions of dollars in state funding to support the implementation of scientifically based instruction. The House’s initial version of its budget bill wisely kept intact the governor’s key literacy proposals, though it reduced some of the funding for the initiatives.

So far, so good. But as we touched on in a recent piece, lawmakers should do more to shore up the literacy plan by adding transparency and enforcement provisions. These would ensure that parents and the public are informed about schools’ curricula decisions and deter schools from refusing to shift to scientifically based reading instruction. Because a number of states have already passed science of reading legislation—Ohio is late to this party—lawmakers can look towards other jurisdictions as models. This piece takes a deeper dive into the sunshine and non-compliance provisions in Colorado and Arkansas.

Colorado’s curriculum transparency law

It’s hard to hold schools accountable for using high-quality curricula when no one knows what’s being used. Unfortunately, program selection remains a black box across most Ohio schools. While the budget bill would require schools to report their grades K–5 reading curricula to the Ohio Department of Education (ODE), there’s no requirement to make that information public. It could simply sit hidden in a state database.

To ensure full transparency, Ohio lawmakers should require the department to publicly report schools’ reading curricula, exactly as Colorado does. Under its reading laws, not only must the Colorado Department of Education collect information about reading curricula, but it also has to post it on their website. Furthermore, local districts and schools are required to provide a link on their own websites to the state’s curricula webpage.

Thanks to this sunshine provision, we learn that Colorado’s two most popular core literacy programs in grades K–3 are Houghton Mifflin’s Into Reading, which receives strong marks from EdReports, and Amplify’s Core Knowledge Language Arts, another highly-rated curriculum that substantially boosts student achievement. We also see that Denver’s schools currently use Core Knowledge, while Boulder Valley disappointingly uses the Fountas & Pinnell whole-language-based curriculum (though recent news reports indicate it’s transitioning under pressure from the Colorado Department of Education).

Arkansas’ enforcement provisions

Public transparency is an important first step in making sure that schools are actually following the reading science. But it’s possible that sunshine will only go so far. In cases when schools are refusing to use evidence-based curricula or playing reporting games, state authorities should step in. Here in Ohio, the state budget bill’s curricula requirements would implicitly give ODE authority to enforce the law. It’s certainly possible that the agency will stringently do this, just as in Colorado. But the Ohio legislature could put even more oomph behind the effort by setting a clear expectation for enforcement and delineating penalties for non-compliance.

On this count, Ohio legislators could take a page from Arkansas’ science of reading legislation, which has particularly strong language on enforcement. First, the state’s Right to Read Act expressly states that its department of education is “vested with the authority to and shall enforce” the state’s reading law. Moreover, state implementation rules describe specific actions—including withholding funding—that must be taken if a district violates the law. Here’s the key language:

If a public school district, including an open-enrollment public charter school, fails to remedy its violation [of state reading laws] within sixty days of notification of its failure to comply, the state board shall direct the Division to withhold a maximum of ten percent of the monthly distribution of state foundation funding aid to the public school district.

Once the state board determines that a public school has complied...the Division shall restore the monthly distribution of state foundation funding aid to the public school district.

This clear legislative directive to enforce the reading law, along with concrete repercussions for non-compliance, signal to schools that Arkansas is serious about strongly implementing the science of reading. They also give the department of education political cover when and if they have to take the difficult step of sanctioning in a local district or school. Finally—and perhaps most importantly—establishing clear penalties for non-compliance is likely to result in quick action in schools that are not following the science.

* * *

Governor DeWine and state policymakers should be strongly commended for their support of scientifically based reading instruction. The budget bill offers an excellent start in removing ineffective instructional practices from Ohio schools and shifting to evidence-based approaches. With some critical finishing touches, lawmakers will make certain that all schools are truly following the science of reading.

Career pathways are emerging as a promising, bipartisan solution to help adolescents and adults secure well-paying jobs and support employers searching for skilled workers. Although their design varies from state to state, these pathways are intended to help participants develop knowledge and skills in a particular career field, typically one that’s considered in-demand. Pathways often include secondary and post-secondary career and technical education (CTE) programs, work-based learning opportunities like internships or apprenticeships, and the opportunity to earn at least one post-secondary credential.

Career pathways programs can be especially promising for young adults. That’s because they’re typically more affordable than a traditional four-year university and don’t take as long to complete. They also offer myriad benefits—including on-the-job learning experience and job-related classroom training, boosted income, and valuable industry-recognized credentials—and they can open the door to well-paying jobs and in-demand careers. Amidst rising higher education costs and an economy that’s roiling in the wake of the pandemic, many advocates view investing in high-quality career pathways programs as an effective strategy to help young adults transition to the workforce.

To shed additional light on how career pathways programs can help young adults, Bellwether recently published a report that examines efforts in three states: Colorado, Texas, and Ohio. These states—which were chosen because they are geographically, politically, and demographically diverse—approach career pathways in vastly different ways. By interviewing policymakers, district leaders, and program administrators in each state, Bellwether was able to identify some common themes. This piece focuses on a few of the big takeaways for Ohio.

Ohio’s case study includes a brief overview of the state’s career pathways landscape—which the authors call “one of the nation’s most complex.” Like other states, Ohio uses Area Technical Centers, or ATCs, to deliver CTE at both the secondary and post-secondary level. The Buckeye State has over 100 ATCs.

At the secondary level, ATCs take the form of career-technical planning districts (CTPDs), which administer CTE programming to middle and high school students. There are currently ninety-two CTPDs in Ohio, and there are three types:

At the post-secondary level, the state has Ohio Technical Centers, which are independent CTE providers that offer training and credentials for in-demand jobs. These institutions primarily focus on career and credential attainment, which separates them from community colleges that typically focus more on degree attainment, and the centers are eligible for federal financial aid authorized under Title IV. OTCs often partner with CTPDs, and may even be co-located. This makes them more efficient, but also adds another layer of complexity to an already intricate system.

In recent years, Ohio lawmakers and leaders have prioritized the growth of pathways programs to help meet the state’s workforce needs. This increasing emphasis and the accompanying investment of state funds makes Ohio a model for other states. According to Bellwether, here are two of Ohio’s strengths and two areas for growth.

Strength: Bipartisanship

One of the common themes identified by Bellwether is that policymakers in all three states have leveraged bipartisan support to expand and improve career pathways initiatives. Ohio, for example, serves as a “striking example of bipartisanship” because of its long history of providing designated funding specifically for career pathways programs in the state’s biennial budget. Even when Ohio’s last Democratic governor had to slash government spending via the budget in the wake of the Great Recession, CTE programs and initiatives remained (and some even saw slight funding bumps). This year’s budget is no different. CTE spending has risen consistently during Republican Governor DeWine’s tenure, and he recently recommended additional increases. His proposal—which is currently working its way through the General Assembly—also charges the Ohio Department of Education with increasing the number of in-demand CTE programs and aims to incentivize schools and businesses to offer work-based learning opportunities to more students.

Strength: Partnerships

Another key factor that explains Ohio’s thriving career pathways sector is state leaders’ efforts to prioritize meaningful public-private partnerships. Bellwether highlighted Youngstown State University’s innovative partnership with IBM, which allows students to participate in a training program that helps them build skills and earn credentials in in-demand fields like cybersecurity, data science, and information technology. But Ohio has plenty of other examples, as well. Business Advisory Councils, which are locally focused bodies aimed at getting education and business leaders to work together to ensure that students have relevant learning experiences, have helped foster partnerships. There are also several state laws and grants aimed at funding collaboration between businesses, education and training providers, and community leaders.

Area for growth: Fighting stigmas

Bellwether notes that in all three states, career pathways programs “often suffer from longstanding stigma about their quality and purpose.” That’s because, in the past, teachers and administrators used them to track students they didn’t think were “fit for college,” and tracking efforts were often steeped in bias against low-income, Black, and Hispanic students. Bellwether acknowledges that although “extensive effort” has gone into addressing these issues and improving programs, stigmas persist. In fact, the Ohio policymakers, advocates, and stakeholders they interviewed identified persistent stigmas as one of the state’s most significant barriers to equitably expanding access and participation. Although Ohio has an “established history” with CTE, many students and families remain unaware of the myriad opportunities that are available to them or are misinformed about what career pathways are and aren’t. Advocates argue that the best way to overcome the public’s lack of knowledge (and persistent skepticism) is to provide state funding to raise awareness about available programs and their positive outcomes.

Area for growth: A lack of data

Of course, Ohio can’t effectively raise awareness without consistent and accurate data. Bellwether notes that, like many other states, Ohio has “fragmented data systems” that prevent leaders from connecting the dots across sectors and getting a full and accurate picture of the state’s career pathways landscape. Without program quality and longitudinal outcome data, it’s difficult to know whether students who earn credentials succeed in securing a job in their field of study, and what kind of wages those jobs pay. And while the impact on students is obviously the most important missing data piece, it’s also crucial to know which pathways have the best return on investment. To take its CTE sector to the next level, Ohio must invest in a robust data system than can help answer questions like these.

***

Over the last year, Ohio’s career pathways programs have been the subject of plenty of research and analysis. Rightfully so, as these programs give Ohioans the opportunity to earn credentials and access well-paying jobs in growing industries. Bellwether’s latest report finds plenty of strengths in the Buckeye State, including state-level efforts to foster partnerships and capitalize on bipartisan support. But Bellwether also identified some opportunities for growth, namely the urgent need for better data on longer-term outcomes. Overall, Ohio has a lot to be proud of—but there’s also plenty of work left to be done.

Ohio’s recent focus on early literacy is largely thanks to Governor DeWine’s budget recommendations, which contain a bold plan to boost reading achievement in Ohio. His proposal would require schools to use high-quality curricula and instructional materials aligned with the science of reading, and would invest millions in state funding to help schools purchase said curriculum and provide professional development and literacy coaches to support teachers.

The governor’s proposal, however, is just the first of many steps in the state budget cycle. Anything he proposes must also earn the approval of the House and Senate before it becomes law. The good news is that House lawmakers preserved many of the governor’s recommendations in their recently released version of the budget, including the adoption of high-quality reading curricula. The bad news is that they also would eliminate the retention requirement of the Third Grade Reading Guarantee.

Over the years, we at Fordham have repeatedly explained why moving away from retention-and-intervention would be a huge mistake. But we’d be remiss not to also point out that backing away from a rigorous policy intended to help kids and hold schools accountable for student progress is very on brand for Ohio lawmakers and leaders. In fact, Ohio has a long history of going all-in on big education policy changes and then backing off when it comes time to implement them.

Last year, during yet another attempt to eliminate third grade retention, I wrote an analysis of how two of Ohio’s most significant education reforms to date—graduation requirements and school improvement efforts in the form of Academic Distress Commissions—mirror the current roller coaster of third grade reading retention. Since lawmakers are back to their old tricks, it unfortunately seems necessary to revisit that analysis of Ohio’s very bad habit of sidestepping high expectations and accountability. Let’s take a look.

Graduation requirements

In 2009, in an effort to address how many students were leaving high school with a false impression of their own readiness for future success, Ohio lawmakers tasked the state board with drafting a new set of graduation requirements. In 2014, the General Assembly passed legislation that offered students in the class of 2018 and beyond three pathways to a diploma. The primary pathway required students to accumulate a certain number of points by passing newly created End of Course (EOC) exams, which replaced the far too easy Ohio Graduation Tests (OGTs). The other pathways required students to achieve a certain score on a college admissions exam or meet career-technical requirements. But by 2016, district superintendents were sounding the alarm about an impending graduation “apocalypse.” They warned that, because the new EOCs were more demanding than OGTs, as much as a third of the class of 2018 might fail to meet graduation standards.

Much like they’re currently doing with third grade reading retention, legislators opted to ignore the reasons they changed the law in the first place and swooped in to “save” the day. They did so by following recommendations from the state board and allowing students to graduate based on alternative pathways such as school attendance, course grades, a senior project, or volunteer hours. These pathways were of abysmal rigor, and several districts took advantage to inflate their graduation rates.

The good news is that, after plenty of additional debate, the state enshrined improved graduation requirements into law. But the roller coaster ride could have been avoided if legislators had stuck with the initial plan.

Academic Distress Commissions

Academic Distress Commissions, or ADCs, are a state-level initiative that required Ohio to intervene in chronically underperforming school districts. For the most part, debate over ADC policy followed an identical pattern to graduation requirements. First, state leaders—including former Governor Kasich—recognized that there were several districts failing to improve academic outcomes, and their persistent underperformance was negatively impacting students. Next, lawmakers significantly strengthened the law by lessening the power of local school boards and empowering CEOs with managerial and operational authority to devise and implement a district turnaround plan. And then, when raising expectations and implementing intervention efforts were met with a firestorm of pushback, lawmakers scrambled to back down.

In 2021, lawmakers used the state budget to create an easy off-ramp for the three districts that were under ADC oversight: Youngstown, Lorain, and East Cleveland. The law removed the CEOs, returned power to local school boards, and charged each board with developing an academic improvement plan that contains annual and overall improvement benchmarks with minimal specific requirements. Unfortunately—but predictably—the approved plans don’t actually promise much improvement. Results from the most recent state report cards offer some bright spots—like Lorain’s four-star rating on the progress component—but mostly indicate that these districts still aren’t improving as quickly as they need to be. For all intents and purposes, they’re right back where they started, and kids are no better off.

***

Recent efforts to repeal third grade reading retention mandates are ill-advised. They ignore a trove of research proving that retention, when coupled with rigorous intervention, can benefit students in the short and long term. They ignore the social and emotional impacts of social promotion. Worst of all, they solidify Ohio as the kind of place where leaders and lawmakers talk a big talk about improving education but repeatedly fail to walk the walk. This is likely why the Buckeye State has made so little progress over time on measures like the Nation’s Report Card. Ohio’s students deserve better than this.

A common concern in evaluating computer-based testing is the perceived differences between students writing by hand and those writing by typing. Historically, typing has been seen as more difficult for students to master—especially younger kids—thus rendering computer-based assessments intrinsically “harder” than pencil-and-paper versions, even when the test material is otherwise identical. But much of the research around the topic is almost a decade old, predating the explosion of online and computer access even our youngest kids (and their teachers) experienced since then, as well as newer research that supports the idea of typing being easier than handwriting. That is, one keystroke—using only one finger most of the time—renders a complete letter rather than a multiple and varied number of pen strokes needed to handwrite any given letter, any one of which can go awry–even for experienced little fingers.

Onto the pile of (almost) up-to-date information we can add brand new findings from Norway. State-run schools in the country were asked to adopt either a handwriting-first or digital-writing-first approach to instruction ahead of the 2018–19 school year. A group of researchers from Volda University College exploited the natural experiment created by comparing the development of writing composition skill among students in five first-grade classes. Half of the children learned to compose text by handwriting on paper and the other half learned by typing on a digital tablet using word-processing software, based on the policies adopted by their schools. All students were evaluated at five separate points during the year by completing the same scheduled narrative writing tasks. All narratives were evaluated in terms of a range of text features capturing both transcription accuracy (spelling, spacing, punctuation) and syntactic and compositional sophistication.

The best news is that all students tended to show strong and similar increases in the accuracy and complexity of their syntax, in the detail and sophistication of their narratives, and in the length of their texts over the school year, with negligible differences based on learning modality. More accurate spelling and word spacing were observed among students in the digital learning group, which the researchers attribute to the software’s inclusion of a text-to-speech function. This allowed students to hear what their typed words sounded like spoken back to them, highlighting misspellings and any words mistakenly strung together or improperly split. Interestingly, students in the digital modality showed lower accuracy with periods, questions marks, and exclamation points than the handwriting group. The researchers surmise that both groups were likely close to the same level of accuracy but that stray marks in the handwriting mode could have been counted as periods by graders, whereas no such moderator existed for kids typing their sentences.

All in all, the researchers suggest that the data represent an even outcome, with both learning modalities proving successful at increasing student growth and achievement in writing. They suggest a number of limitations of both the study design (in 900 hours of instruction over the year, for example, could digital-first teachers have reverted to handwriting for some kids during some lessons?) and the generalizability of their findings (English language instruction with its multiple irregular word structures, they say, would be a very different context to test). They also spend some time discussing the value of the text-to-speech functionality and whether it really represents a positive learning support or a sort of “cheat” for students who use it. On the other hand, might there be some analogous version of that feedback to be incorporated into handwriting-first instruction? Could that then make handwriting superior?

All of this takes on greater significance after years of pandemic-required remote learning and the ongoing utilization of online resources in its wake. At a minimum, it seems, the old mindset that handwriting is an inherently easier learning mode needs to be retired. But beyond that is the future, in which we can merge all the tools and modalities available to provide the very best learning opportunities for students.

SOURCE: Eivor Finset Spilling et al., “Writing by hand or digitally in first grade: Effects on rate of learning to compose text,” Computers and Education (April 2023).

Providing students with tutoring in addition to in-class learning time is an oft-prescribed remedy for both catching up students who are behind and accelerating students who are capable of even higher performance. Two common sticking points to providing that remedy are finding additional time in the day, week, or year for the intervention and finding enough qualified personnel. A new study from the National Student Support Accelerator (NSSA) evaluates a promising program that could reduce both of these sticking points to manageable levels.

Chapter One is a nonprofit group (formerly known as Innovations for Learning) founded thirty years ago to help leverage emerging technology and volunteers in an effort to boost the reading skills of children in Chicago. Today, its reach is international, but it remains dedicated to helping students in grades K–2 become fluent readers. During the 2021–22 school year, Chapter One partnered with a large, unnamed school district in Florida to conduct a randomized controlled trial of its tutoring program. Fifty-six percent of students’ families in the district qualify for free and reduced priced lunch, and 12.6 percent of students are English learners. The district chose forty-nine kindergarten classes across thirteen schools to participate. While the report covers only the first year of results, students who remained in the district were expected to receive Chapter One tutoring during first grade (2022–23), as well, and those results will be published later. Researchers plan to follow all participants who remain in the district through the end of third grade.

The first year of the study consisted of 818 kindergarten students, roughly half of whom were randomly assigned to receive Chapter One tutoring. The two groups were similar in terms of demographics, although the treatment group did have slightly lower initial scores on the Florida Kindergarten Readiness Screener (FLKRS). This was controlled for in the final analysis.

The Chapter One tutoring model embeds part-time early literacy interventionists (ELIs) in schools. These ELIs meet with students one-on-one in the back of their classroom during the school day, thus eliminating the sticking point of “finding additional time for tutoring.” One ELI serves multiple classrooms in a building and tutors individual students in five to seven minute sessions during blocks of reading instruction or at other opportune moments. The short sessions are intended to forestall loss of student attention while allowing each session to focus on a progression of discrete skills. The length of a given session and the number of sessions per week is determined by student need and rates of progress. For instance, students who are making adequate progress may only meet with their tutor once or twice a week, whereas students whom the tutors identify as in need of more support may meet daily.

ELIs follow a digital curriculum created by Chapter One, facilitating the assessment and tracking of student performance over time and allowing less-experienced individuals to serve as ELIs. While some ELIs are former classroom teachers, most have no teaching experience or teaching certification. All ELIs have earned at least a bachelor’s degree and undergo an extensive series of online training courses. All of these efficiencies combine to maximize the number of students one ELI can serve—thus addressing the “finding enough personnel” sticking point—and to squeeze the most instruction into the shortest amount of time.

The tutoring curriculum moves students through phonics development, learning to segment and blend short and long vowel sounds, learning sight words, and learning strategies to fluently read both texts that are readily decodable and those that include words that can’t be easily sounded out. Its format is said to draw on a strong evidence base. Students in the treatment group are also given tablets with the Chapter One software and asked to work independently for fifteen minutes each day, with the assigned work being precisely aligned to their most recent tutored instruction. ELIs also regularly meet with teachers, reading coaches, and principals to share information on student progress.

How did it work? Treatment group students were 38.1 percentage points more likely to reach the target reading level (or higher) by the end of kindergarten than their control group peers (nearly 70 percent of treatment students versus 32 percent of control students). Treatment group students were, on average, one reading level ahead of control group students at the end of the school year and achieved growth of 1.12 levels during the year. Importantly, native English speakers and English learners in the treatment group both showed similar levels of achievement and growth. Treatment group students scored, on average, 0.23 standard deviations higher than their peers on a year-end oral reading fluency assessment. Scores on the district’s kindergarten reading assessment were not fully available, but among the available data, evidence suggests a small but statistically significant boost for students who received the Chapter One tutoring treatment. The lack of full data likely contributes to this lackluster outcome, but we cannot discount the possibility that the new tutoring program may not be fully aligned with existing district assessments.

The NSSA researchers conclude that Chapter One is an effective, scalable, and affordable model for one-to-one tutoring. More data—which are on the way—are likely needed to fully support the claim of effectiveness, but first-year results certainly seem promising. Ditto for the model’s efficient use of time and talent. As to affordability, the researchers note that Chapter One cost the district $375 per student, a price tag that covers ELIs (pay, background checks, training, etc.), all the necessary technology, and other indirect costs for implementation. In districts with more than 5,000 students, the cost increases to $450 per student to fund an ELI manager position. The researchers assert that this is “substantially lower than the vast majority of other tutoring programs.”

Committing millions of dollars per year for multiple years is no small ask of any school or district, especially as federal Covid funding dries up. But much worse remediation efforts have been bought and paid for before, and the early data for this program certainly seem promising.

SOURCE: Kalena Cortes, Karen Kortecamp, Susanna Loeb, and Carly D. Robinson, “A Scalable Approach to High-Impact Tutoring for Young Readers: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial,” National Student Support Accelerator (February 2023).

Too many Ohio students are academically adrift. Without serious help, many will falter when trying to tackle college or launch careers. This situation has existed for decades, but it’s worse today—far worse—due to the pandemic. Consider just a few alarming numbers from the 2021–22 state assessments. Compared to 2018–19, just prior to the pandemic, statewide math proficiency rates are down ten percentage points in fourth and sixth grade and down fourteen points in eighth grade. Proficiency rates in high school algebra and geometry exams are down twelve and eight points, respectively. Reading proficiency rates, while recovering in fourth and sixth grade, are down five points in both eighth grade and high school.

The declines are steeper among economically disadvantaged students, students with disabilities, English learners, and Black and Hispanic students—thus widening achievement gaps that were already unacceptable before the pandemic hit. Compared to 2018–19, the math proficiency rate of economically disadvantaged students slid by fourteen percentage points in grades 3–8—a larger decline than nondisadvantaged students (ten points). Math proficiency rates for Black and Hispanic students in those grades fell by thirteen points, while rates decreased by ten and eight points for White and Asian students, respectively.

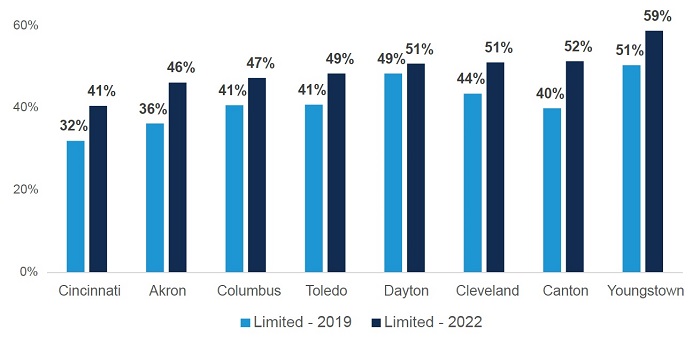

Plummeting proficiency rates translate into larger numbers of students with severe math and reading deficiencies. According to the Ohio Department of Education (ODE), students scoring at the “limited” achievement level—the lowest mark on state exams—demonstrate “minimal command” of grade-level standards. Stated bluntly, students in this category are failing academically, and unless they receive swift and serious help, they are on a pathway to functional illiteracy and innumeracy. Yet alarming percentages of Ohio students are now scoring at this level. In the Big Eight urban districts, about one in every two students—roughly 90,000 students—were “limited” in 2021–22.

Figure ES-1: Percentage of students scoring “limited” on state exams in Big Eight districts

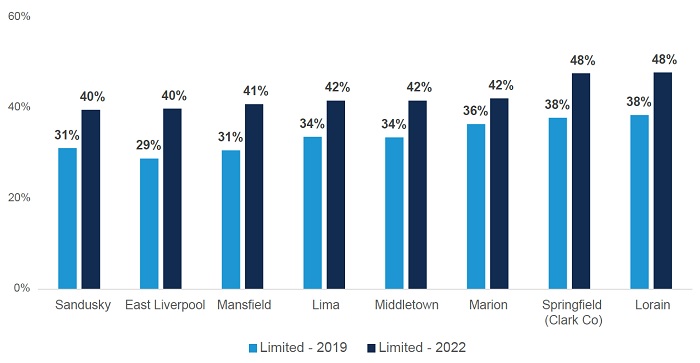

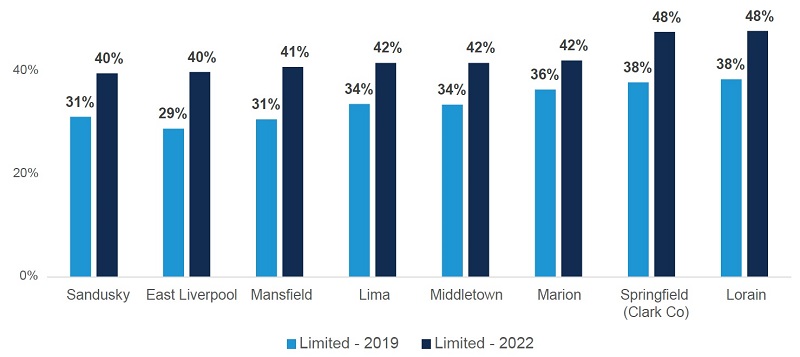

Academic catastrophe is not just a “big-city problem,” either. Figure ES-2 indicates that more than two in five students in midsized districts such as Middletown, Marion, Springfield, and Lorain scored at the lowest achievement level on state exams last year. And statewide, about one in four Ohio students—some 400,000 children—are now struggling to grasp even the most basic grade-level concepts.

Figure ES-2: Percentage of students scoring “limited” on state exams in selected midsized districts

Ohio is not alone, of course, in racking up terrible Covid-related learning losses, but the bad news keeps coming.[1] Last October, just a month after the release of state exam results, came the release of the 2022 results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a.k.a. the “Nation’s Report Card.” These test data reveal yet again the massive learning losses among students in Ohio and across the nation. It also indicated that Ohio’s Black and Hispanic students fared even worse than their national counterparts during the pandemic.[2]

This situation can be reversed but only if state and local leaders push for aggressive recovery efforts in Ohio schools. There is some evidence that students made more academic progress in 2021–22 than in a typical pre-pandemic year, likely reflecting schools’ ramped-up efforts to remediate learning losses. Progress, however, has been uneven: older students seem to be recovering at slower rates than their younger peers, and progress in math has been more muted than in reading.

Ohio still has much work ahead to ensure that the state’s Covid generation gets back on track. This report concludes with four policy recommendations that could bolster these efforts. They include ideas that aim to directly address the impacts of the pandemic (e.g., tutoring and summer school), as well as broader reforms that would strengthen the state’s K–12 education system as a whole and support higher achievement across Ohio.

Here’s the short version, with more detail to be found starting here.

***

Everyone knows the tumult and setbacks brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic. Businesses closed, schools were shut, and millions of Americans “sheltered in place.” Far too many took ill and died. Yet even without schools to attend—and often slipshod experiences with the online replacements—time ticked on for Ohio students. The vast majority will still end their high school journey—ready or not—at the age of eighteen. Therein lies the challenge. Can Ohio restore to those learners what they lost while schools were closed and their lives were disrupted? Of course it can. But will it? The answer to that question hinges on the actions of today’s leaders.

In March 2020, with the pandemic bearing down on the entire nation, schools across Ohio shut their doors and struggled to shift to remote learning. State assessments scheduled for that spring were cancelled, and accountability policies such as school report cards were suspended. The disruptions continued into the fall, as schools dealt with the public health crisis in various ways—some offering only a remote option, others a hybrid model, and still others opening for full-time, in-person instruction. With most Ohio schools returning to a semblance of normalcy by spring 2021, the state restarted its annual exams and released test results (though it again paused report card ratings for the year).[3]

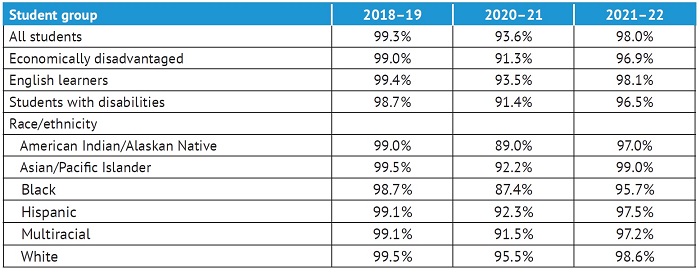

Test participation that year was spotty. As table 1 shows, 93.6 percent of Ohio students took exams in 2020–21, though rates were lower among economically disadvantaged, special-education, and Black students. Nevertheless, the assessments gave an early picture of the learning losses that had occurred. One study by Ohio State University professors Stéphane Lavertu and Vladimir Kogan estimated losses of one-third to a full year of learning, depending on grade level and subject.[4] Sharp declines in student proficiency rates were also visible (see figures 1 and 2 below).

By fall 2021, Ohio schools had reopened for in-person instruction. Participation in state assessments rose in 2021–22, almost reaching the near-universal rates seen prior to the pandemic. Statewide, 98 percent of Ohio students took state exams last spring, though slight differences in participation still appear by student group. The state also rebooted its school report card system and assigned school ratings, though it continued to suspend policies that require certain state actions as a result of poor performance on report card measures.[5]

Table 1: Statewide participation rates in state assessments, 2018–19 to 2021–22

Thanks to more accurate data from spring 2022 state testing, a clearer picture of where Ohio students stand academically—and how much progress is being made—has emerged. The following offers four takeaways.

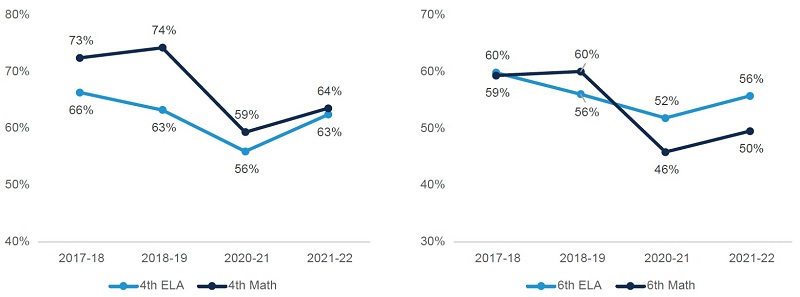

Takeaway 1: Mixed recovery in student achievement

The latest data reveal a mixed picture of academic recovery in Ohio. In the earlier grades, there is some evidence of improvement post-pandemic. Figure 1, for instance, shows a fairly strong rebound in fourth- and sixth-grade English language arts (ELA) and math. In ELA, fourth- and sixth-grade proficiency rates in 2021–22 actually track closely with the pre-pandemic rates from 2018–19. Fourth- and sixth-grade math proficiency rates also increased relative to 2020–21 yet remain well below pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 1: Student proficiency in fourth- and sixth-grade math and ELA, 2017–18 to 2021–22

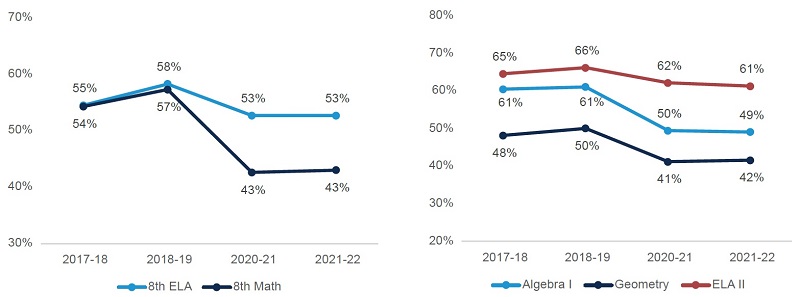

Unfortunately, recovery is stagnant in the higher grades. Figure 2 shows no gains in proficiency in eighth-grade math nor in ELA. Proficiency in both subjects remains well below pre-pandemic rates. There is also little evidence of recovery in high school. Proficiency on the state’s Algebra I and English II exams actually slid by one percentage point relative to 2020–21, while it ticked up just one point in geometry. On all three of these high school end-of-course exams, proficiency rates remain well below pre-pandemic rates.

Figure 2: Student proficiency in eighth grade and selected high school end-of-course exams, 2017–18

to 2021–22

Takeaway 2: Large and widening achievement gaps

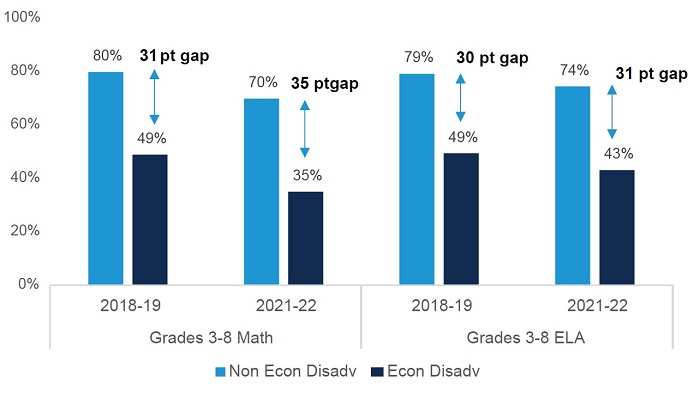

For decades, education analysts have documented wide and worrying achievement gaps between disadvantaged students and their peers. While these gaps have slightly narrowed over time,[6] substantial disparities remained in the years just prior to the pandemic. In Ohio, for example, just 28 percent of economically disadvantaged students achieved proficiency on their eighth-grade exams in 2018–19, while 59 percent of their nondisadvantaged peers—more than twice the proportion—did so.

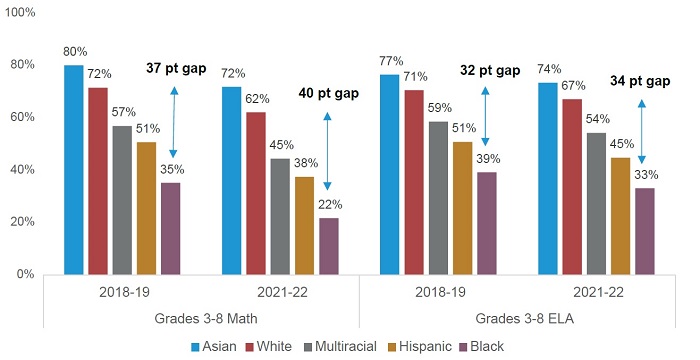

Disadvantaged students were at greater risk of serious learning loss during the pandemic. Their schools were more likely to stay closed longer, and many had fewer at-home resources to compensate. The figures below clearly show that the pandemic took a greater toll on Ohio’s neediest students, thus widening the preexisting achievement gaps. Figure 3 shows that the Black-White gap in third- through eighth-grade math widened from thirty-seven to forty percentage points between spring 2019 and spring 2022. The results are similar in ELA, with the Black-White gap growing from thirty-two to thirty-four percentage points in these grades (though not directly reported on the figure, the Black-Asian and Hispanic-Asian/White gaps grew, as well).

Figure 3: Proficiency rates in third through eighth grades by race/ethnicity, 2018–19 to 2021–22

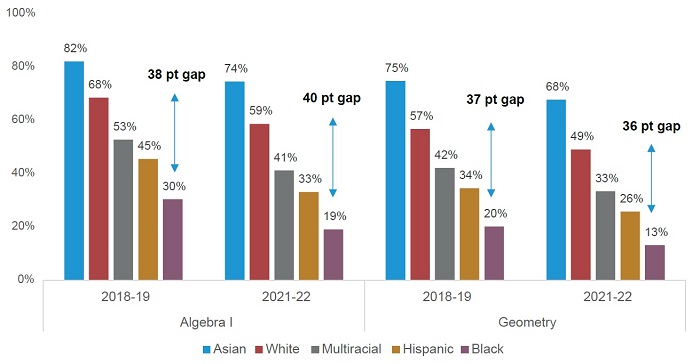

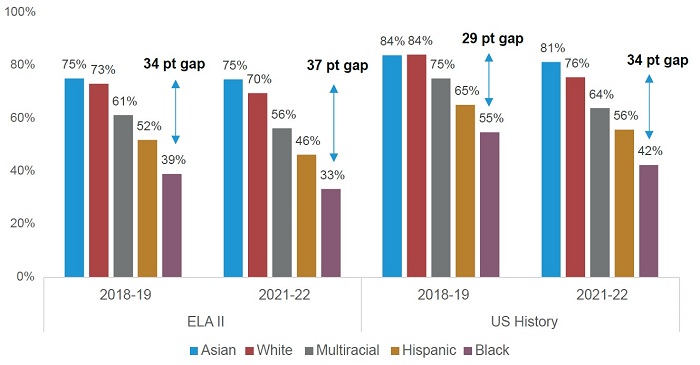

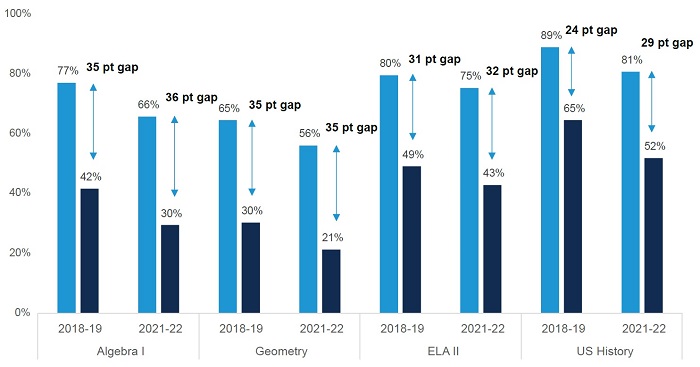

Similar gaps are seen in high school. On the two math exams, large gaps of thirty-five percentage points or more emerge between Black and White students, with the gap slightly widening in algebra but narrowing by one point in geometry. The achievement gaps on the high school English II and U.S. History exams are similar and grew by three and five percentage points in the respective subjects.

Figure 4: High school math proficiency rates by race/ethnicity, 2018–19 to 2021–22

Figure 5: High school English and U.S. History proficiency rates by race/ethnicity, 2018–19 to 2021–22

Large disparities in math and reading proficiency also exist between economically disadvantaged students and their nondisadvantaged peers. Figure 6 shows that differences in math proficiency by disadvantaged status grew by four percentage points in grades 3–8, while increasing by one point in ELA. Gaps in high school were unchanged to slightly wider, depending on the subject. Disparities by special-education and English-learner status are substantial and generally grew larger during the pandemic; those data appear in Appendix A.

Figure 6: Proficiency rates third through eighth grades by economic disadvantage, 2018–19 to 2021–22

Figure 7: High school proficiency rates by economic disadvantage, 2018–19 to 2021–22

Takeaway 3: Severe academic challenges are widespread

Another way to look at the academic challenges facing Ohio is to examine the number of students who score in the lowest of the five achievement levels on state tests, which is somewhat politely called “limited.” Such students are clearly struggling to achieve even the most basic grade-level standards. ODE says they “demonstrate a minimal command” of grade-level standards, and this is the level reached by students who earn just 25 to 35 percent of the points possible on their state tests.[7] Without serious help and supports, students scoring at this level are highly likely to face functional illiteracy and innumeracy later in life.

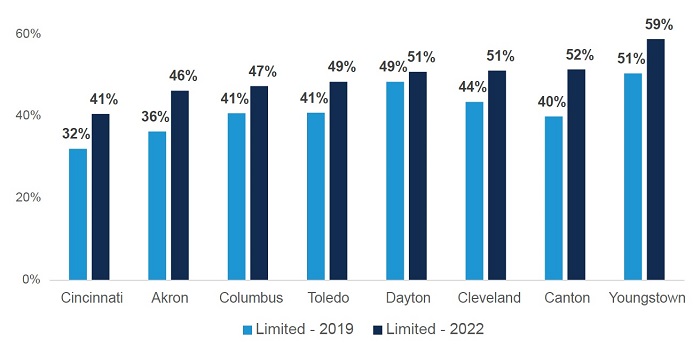

The problems in math and reading are greatest in Ohio’s high-poverty urban schools, but they are not confined to them. Figure 8 first shows the percentage of students scoring at the limited level in the state’s Big Eight districts. Prior to the pandemic, about two in five students in those cities scored at the “limited” level, but by spring 2022 that number had risen to roughly half. The highest rate of academic failure was in Youngstown, where a staggering 59 percent of students scored at this level, while Cincinnati had the lowest percentage (41 percent). With 182,000 students attending school in these eight districts, the data indicate that roughly 90,000 students are having serious difficulties achieving grade-level standards. And that, once again, is in just eight cities.

Figure 8: Students scoring “limited” on state exams, Big Eight districts, 2018–19 and 2021–22

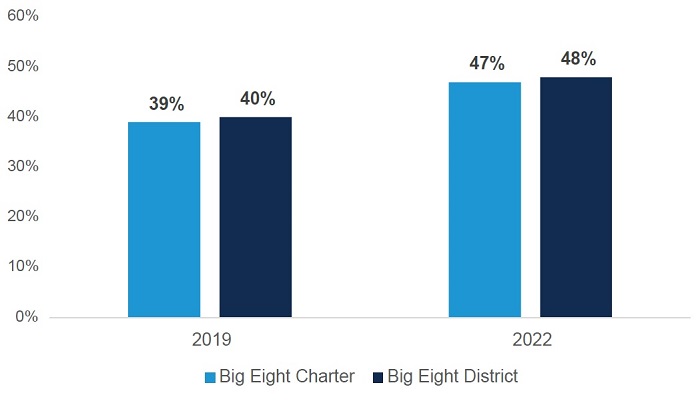

Growing numbers of low-achieving students are also enrolled in the public charter schools that operate in these cities. Figure 9 shows that nearly half of Big Eight charter pupils scored at the “limited” level in 2021–22, a percentage that tracks closely with their district counterparts.

Figure 9: Students scoring “limited” on state exams, Big Eight charter and district, 2018–19 and 2021–22

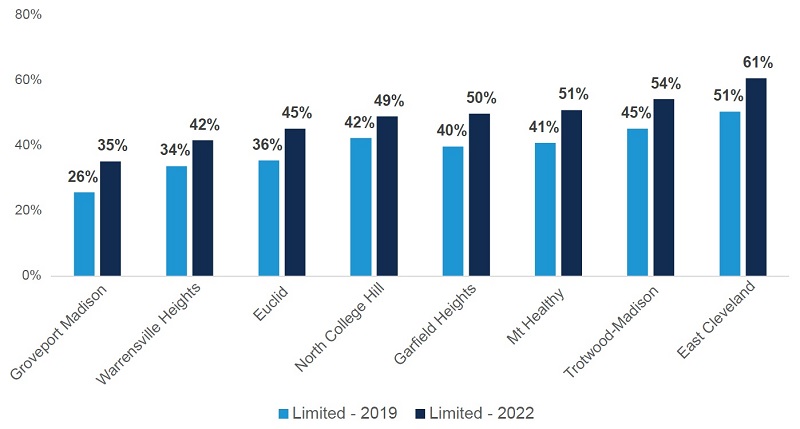

Serious academic deficiencies are also evident in Ohio’s inner-ring suburbs and higher-poverty small towns. Figure 10 shows the significant proportions of limited students in several districts surrounding Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, and Dayton. In the 2,500-pupil district of Trotwood-Madison, for example, 54 percent of students scored at “limited” in spring 2022, while 61 percent of students in East Cleveland did so.

Figure 10: Students scoring limited on state exams in selected suburban districts, 2018–19 and 2021–22

Finally, we see that two in five students in several of Ohio’s small-town districts scored in the limited category last year. Forty-two percent of students in Lima, Middletown, and Marion scored at that level in 2021–22, while nearly half of those in Springfield and Lorain did so.

Figure 11: Students scoring limited on state exams in selected small-town districts, 2018–19 and 2021–22

Takeaway 4: Acceleration is uneven by grade, subject, and subgroup

Given the large learning losses discussed above, schools need to “accelerate” student learning faster than the pre-pandemic pace of academic growth. Such acceleration is especially critical for disadvantaged students who already face significant learning gaps and struggled most during the pandemic. But how fast did student learning grow from 2020–21 to 2021–22? Was it any faster than during pre-pandemic years? And are disadvantaged students making quicker progress than their peers?

To examine the “pace” of learning, we rely on an in-depth analysis of state assessment results that was published by Professor Vladimir Kogan of Ohio State University. His analyses, which track students’ learning trajectories over time, compare math and ELA growth from 2020–21 to 2021–22 to pre-pandemic growth rates between 2017–18 and 2018–19. Here’s what he found.

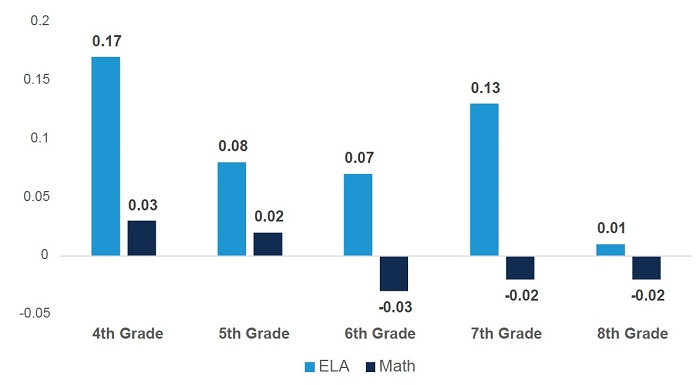

Figure 12 displays growth results by grade and subject in grades 3–8. Positive values indicate that students in a particular grade and subject made more growth from 2020–21 to 2021–22 than pre-pandemic cohorts; conversely, negative values indicate slower growth. On the positive side, students in grades 4–8 made more than typical progress in ELA. However, stronger-than-usual growth in math was less consistent, with slightly more than typical growth seen in grades 4 and 5 but less growth than usual occurring in grades 6–8. It’s hard to be sure what’s behind the stronger growth in the earlier grades, but it’s possible that greater participation in summer learning opportunities may be playing a role. Based on an analysis of third-grade test scores, which—unlike other grades—are administered in both fall and spring, Kogan suggests that the gains in that grade were made largely over the summer.

Figure 12: Annual growth from 2020–21 to 2021–22 versus pre-pandemic

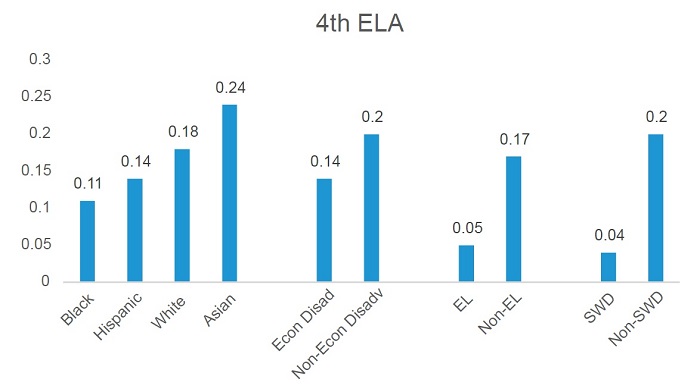

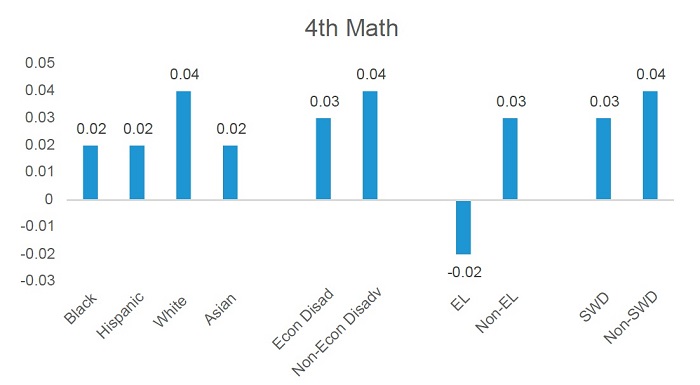

As for the achievement growth of historically disadvantaged students versus their peers, the results are somewhat disappointing. Looking at the fourth-grade data, for example, we see that disadvantaged students made somewhat less progress in both ELA and math than other student groups. Although disadvantaged students made more-than-usual progress last year, their nondisadvantaged peers posted even stronger gains.[8]

Figure 13: Fourth-grade annual growth from 2020–21 to 2021–22 versus pre-pandemic by subgroup

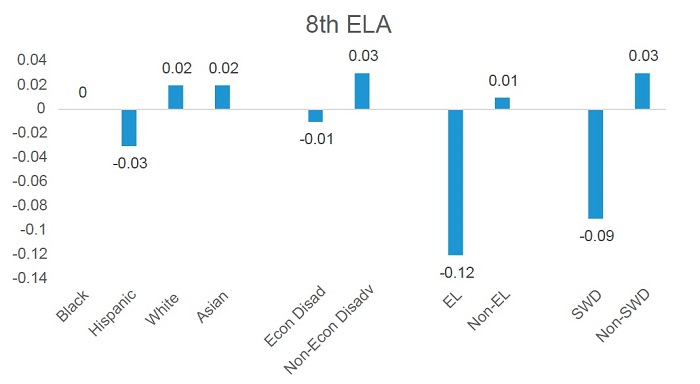

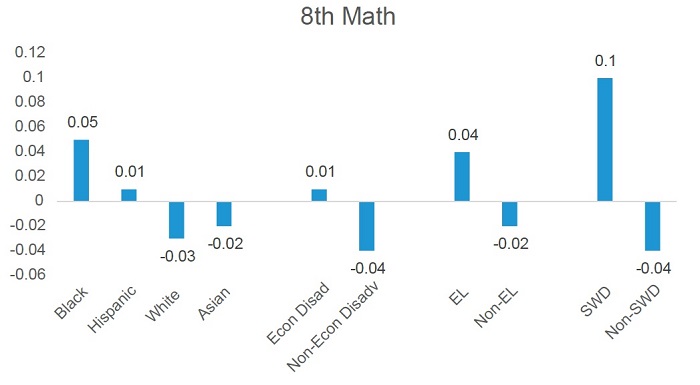

The results in eighth grade are more mixed. In ELA, historically disadvantaged student groups made less progress than their peers, but in math they made more progress.

Figure 14: Eighth-grade annual growth from 2020–21 to 2021–22 versus pre-pandemic by subgroup

Based on his analyses of the growth data, Kogan concludes as follows:

Unfortunately, there was no consistent evidence that student groups who suffered the most pronounced initial declines in the first year of the pandemic—particularly Black students, economically disadvantaged students, and those attending districts that remained remote the longest—have recovered any faster than their peers. In other words, the achievement gaps that expanded early in the pandemic largely remained last year.

In the end, the data are clear: Ohio students lost significant ground during the pandemic—and recovery remains too slow and uneven, with disadvantaged students struggling most to get back on track.

Student achievement in Ohio suffered greatly during the pandemic. Remote education was mostly a disaster, and many schools and students lost their academic edge. Thankfully, schools have returned to normal, and some academic rebound is evident in the data. Yet the persistent learning losses, wide achievement gaps, and uneven post-pandemic progress call for policy actions that can ensure that all Ohio students get back on track. To move the needle faster, we offer four recommendations for state policymakers. The ideas include more targeted initiatives, such as increased use of high-dosage tutoring, that schools should implement to directly address the impacts of the pandemic, as well as broader reforms that would position Ohio’s overall K–12 education system for greater success over the long term.

The unprecedented events of the pandemic knocked tens of thousands of Ohio students off-track. But Ohio’s Covid generation will still need the same knowledge and skills that their predecessors acquired to succeed in life after high school. Their employers aren’t going to give free passes if they can’t compose a coherent email or keep count of expenses. A less-skilled workforce will be a drag on Ohio’s economy, leaving the state with a diminished capacity for innovation and scientific progress.[20] The good news, however, is that state leaders can avoid these consequences by taking action today on behalf of Ohio’s students. Are they up for this a once-in-a-lifetime challenge? Let’s hope so. Students and families are counting on it.

[1] For a review of national studies on the pandemic’s impact on student performance, see Sarah Cohodes et. al., Student Achievement Gaps and the Pandemic: A New Review of Evidence from 2021–22 (Tempe, AZ: Center on Reinventing Education, August 2022). For in-depth analyses of Ohio data, see Vladimir Kogan and Stéphane Lavertu, How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Student Learning in Ohio: Analysis of Spring 2021 Ohio State Tests (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University, February 2022), and Vladimir Kogan, Assessing the Academic Recovery of Ohio Students: An Analysis of Spring 2022 Ohio State Tests (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University, September 2022).

[2] For an overview of those results, see Aaron Churchill, “Ohio’s dismal NAEP results demand an assertive policy response,” Ohio Gadfly Daily, October 25, 2022.

[3] State exams are given in grades 3–8 math and ELA, grades 5 and 8 science, and high school Algebra I, Geometry, English II, Biology, U.S. History, and U.S. Government. Save for one of the high school math exams as well as the U.S. History and U.S. Government exams, all of these assessments are required under federal education law.

[4] Kogan and Lavertu, How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Student Learning in Ohio.

[5] Ohio’s revamped report-card system and the ratings from 2021–22 are discussed in Aaron Churchill, Fine-Tuning Ohio’s School Report Card (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, January 2023). The main consequences for schools that were put on hold include identification of districts for academic distress commissions and automatic closure for low-performing charter schools.

[6] M. Danish Shakeel and Paul E. Peterson, “A half century of student progress nationwide,” Education Next 22, no. 4 (August 2022).

[7] The “performance-level descriptors” for each grade and subject are available at Ohio Department of Education, “Performance Level Descriptors.” For the raw test scores that equate to the various achievement levels, see Appendix H in Cambium Assessment, Annual Technical Report: Ohio’s state tests in English language arts, science, and social studies, 2020-2021 school year (Washington, D.C.: Cambium Assessment, October 2021).

[8] Subgroup results for all grades 4–8 are reported in Kogan, Assessing the Academic Recovery of Ohio Students.

[9] Learning Heroes, “Hidden in Plain Sight: A way forward for equity-centered family engagement” (research deck, Learning Heroes, June 2022).

[10] Dan Silver, Anna Saavedra, and Morgan Polikoff, “Low parent interest in COVID-recovery interventions should worry educators and policymakers alike,” Brookings Institution, August 16, 2022.

[11] ODE’s web page “Family Score Reports Interpretive Guide” includes links to the score report template.

[12] See ODE’s web pages “Summer Learning and Afterschool Opportunities Grants,” and “Statewide Mathematics and Literacy Tutoring Grants.”

[13] Carly D. Robinson et. al., “Accelerating Student Learning with High-Dosage Tutoring” (brief, Design Principles Series, EdResearch for Recovery, February 2021).

[14] Catherine H. Augustine and Heather L. Schwartz, “Summer Learning Is More Popular Than Ever. How to Make Sure Your District’s Program Is Effective,” Rand Corporation, March 30, 2022.

[15] In reading, effective instruction has become known as the “science of reading,” an approach that emphasizes phonics, vocabulary, and background knowledge for fluent reading. For accessible coverage, see Emily Hanford’s work at American Public Media.

[16] Cory Koedel and Morgan Polikoff, Bang for Just a Few Bucks: The Impact of Math Textbooks in California (Evidence Speaks Reports, Vol 2, #5, Economic Studies, Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., January 5, 2017).

[17] Robert Pondiscio, “Louisiana Threads the Needle on Ed Reform,” Education Next 17, no. 4 (July 25, 2017), and Ariel Gilreath, “Retraining an Entire State’s Elementary Teachers in the Science of Reading,” Hechinger Report, November 10, 2021.

[18] Ohio bases economically disadvantaged identification on eligibility for subsidized meals, which has historically been open to students from families with incomes at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level. Under a 2010 federal policy change known as the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), certain districts and schools may offer all students subsidized meals, regardless of their income. This results in inflated—100 percent—economically disadvantaged rates across many Ohio schools. For more on CEP, see ODE’s web page, “Community Eligibility Provision.”

[19] For more on direct certification, see ODE, “Direct Certification Manual” (2022).

[20] For projections of the potential long-term toll of learning loss on economic outcomes, see Kristen Blagg, The Effect of COVID-19 Learning Losses on Adult Outcomes (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, Income and Benefits Policy Center, February 2021), and Eric A. Hanushek, “The Economic Cost of the Pandemic: State by State” (essay, Hoover Education Success Initiative, Hoover Institution, January 2023).

NOTE: Today, members of the Ohio House Finance Committee received testimony on the education provisions of Substitute House Bill 33, establishing the operating budget for the state for the next biennium. Fordham’s Ohio Research Director Aaron Churchill submitted Interested Party testimony relating to early literacy and the retention provision of Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee. These are his written remarks.

My name is Aaron Churchill, and I am the Ohio Research Director at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C. Our Dayton office, through the affiliated Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, is also a community (charter) school sponsor.

As a longtime supporter of educational choice, we’re pleased to see the steps that the budget bill takes to strengthen Ohio’s school choice programs. The additional expansion of EdChoice scholarship eligibility to 450 percent of the federal poverty level will allow more middle-class families to access private schools that fit their child’s needs. We are also pleased that the budget bill maintains the governor’s enhanced funding for high-quality charter schools. While there is still work to ensure that all charters are funded equitably, these supplemental dollars will help narrow funding gaps for quality charters and give them the capacity to serve more Ohio students.

Beyond choice, strong classroom instruction can also open doors for lifelong student success. We commend House lawmakers for preserving the governor’s key literacy priorities, including the required adoption of high-quality reading curricula and the proscription on the disproven, ineffective instructional method known as “three-cueing.” No school in Ohio should encourage its students to guess at words.

Yet we are also deeply concerned about Substitute HB 33’s proposed elimination of Ohio’s third-grade reading retention requirements. The data are clear: Children who cannot read proficiently at the end of third grade are far more likely to struggle in middle and high school, and are at serious risk of dropping out. As we all know, high school dropout is associated with myriad negative adult outcomes, such as increased unemployment, depressed wages, worse mental and physical health, and increased rates of criminal behavior.

Enacted by Ohio lawmakers in 2012, the retention provision in the Third Grade Reading Guarantee aims to ensure that students with severe reading deficiencies aren’t falling through the cracks. The policy requires schools to give struggling students the extra time and intensive interventions needed to become strong readers before they are promoted to the fourth grade.

Make no mistake: Without this policy, schools will quickly relapse into “social promotion,” a harmful practice that pushes children along regardless of their knowledge and skills. Without intervention, such students are likely to become frustrated and discouraged with school, and too many will eventually drop out in high school.

Rigorous studies indicate that this downward spiral can be dramatically altered when states require early intervention. Consider the following studies, all of which rely on a rigorous statistical method that compares the academic trajectories of retained students to extremely similar students who narrowly pass the state’s third grade reading requirement.

These analyses give us confidence that retention benefits struggling readers and puts them on surer pathways. While no study of similar rigor has been conducted in Ohio, it’s worth noting that prior to the pandemic Ohio cut its percentage of students scoring at the “limited” level on third grade reading exams from 27 to 14 percent between 2016 and 2019. This suggests that progress was being made in Ohio with the retention provision in place.

We urge you to reconsider the proposed elimination of the state’s reading retention requirement. With the governor’s emphasis on the science of reading—including a focus on phonics—fewer third graders will likely need to be held back. That’s great news. But Ohio has promised that all students will leave third grade with the reading skills needed to succeed academically in fourth, fifth, sixth grade—and beyond. Maintaining the retention provision will ensure that each and every child is well-positioned for lifelong success. Removing this provision, on the other hand, may placate adults in the system, but will lead to academic struggles and social and emotional stress down the road for students. Please put the needs of kids first.

Thank you for the opportunity to submit written testimony.