As Governor Mike DeWine asserted, the state of Ohio has “a moral obligation” on behalf of students to step in when schools are falling short of academic performance standards. Under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), federal lawmakers have given states the ability to chart their own course when it comes to fixing under-performing schools. Shifting authority—and responsibility—to state policymakers is sensible. But state leaders can’t put school improvement on autopilot and hope for the best.

Our latest report analyzes ESSA’s school improvement requirements and how they have been implemented in the Buckeye State over the years. It also offers eight research-backed recommendations to help strengthen Ohio’s efforts going forward.

NOTE: To access a list of schools in comprehensive support and improvement status as of August 2022, please download this Excel file. The file includes school location, enrollments, and key academic data.

* * * * *

Executive summary

Ohio policymakers have consistently voiced support for rigorous education standards and ensuring that all students have the knowledge and skills needed to succeed after high school. Despite the aspirational talk, however, they haven’t always walked the walk. Instead, Ohio has gotten into a worrying habit of backing down when “real” accountability measures come online. One example is state interventions in poorly performing school districts. After years of pressure from the public education establishment, last year, state lawmakers threw in the towel and offered easy off-ramps to three districts being overseen by academic distress commissions (ADC).

Yet in the midst of the ADC debates, Governor Mike DeWine said, “The state has a moral obligation to help intervene on behalf of students stuck in failing schools.”[1] He’s right. State leaders have a duty to step in when schools are falling far short of performance standards. Students receiving a substandard education are more likely to struggle in the job market, disengage from civic life, and suffer social isolation. Because of the long-term damage that a poor education can do to students (and to the future of the state, as well), policymakers can’t turn a blind eye to failing schools.

But rather than trying to turn around entire districts—bureaucratic systems resistant to change— what if Ohio’s policymakers focused instead on fixing individual schools? The latter approach may be less politically contentious and would better target interventions at the units that actually deliver instruction to students. It also wouldn’t be a new idea, as states have for two decades been required under federal law to identify their lowest-performing schools and work to improve them. Passed in December 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)—the latest iteration of the main federal K–12 education law—maintains this requirement. But in a turn from the prescriptive approach of its predecessor No Child Left Behind (NCLB), ESSA offers states greater flexibility in how they design and implement school improvement programs.

Scant attention has been paid to Ohio’s school improvement policies under ESSA. That likely reflects the intense focus in recent years on district-wide ADCs, as well as unfamiliarity with federal law.

It’s also due to the pandemic, which has paused school accountability policies writ large, including consequences for performance. And perhaps, after seeing mixed turnaround results in Ohio and nationally, some may pay it little heed because they no longer believe that state involvement in low- performing schools is worth it.

Given the formidable challenges of effective school turnaround, one strategy is to simply close failing schools and focus on expanding quality options. To its credit, Ohio has historically pursued policies that create more quality educational options, especially in parts of the state that lack them. Though not the topic of this paper, Ohio leaders should absolutely continue to promote the growth of excellent schools and encourage the closure of dysfunctional ones.[2] Given their decades-long decline in enrollment—recently exacerbated by the pandemic—Ohio’s large urban districts may need to close schools in the coming years. In any closure plan, district officials should work to shutter its poorest-performing schools, which are apt to be underenrolled, and support student transitions to higher performing schools.[3]

Beyond closure, a second, complementary avenue—the topic of this report—is to try much harder to turn schools around. Repairing broken schools is a more intensive approach, but there is evidence that, in some contexts, it can boost learning outcomes.[4] In the Buckeye State, for instance, two studies of its pre-ESSA improvement programs found positive results in schools where significant reforms took place.[5]

As a moral obligation and federal requirement, Ohio should continue working toward better outcomes in its lowest-performing schools. To increase the likelihood of success, policymakers need a well- structured improvement program. But few in Ohio have a clear understanding of ESSA’s school improvement requirements and what the state is doing in this area. This report aims to provide an introduction. To be sure, it doesn’t contain every answer about how the program functions in practice, nor is it a formal evaluation of effectiveness. Rather, it aims to offer useful baseline information, flag areas that merit further attention, and suggest ideas that could strengthen Ohio’s program.

So how does school improvement work under ESSA?

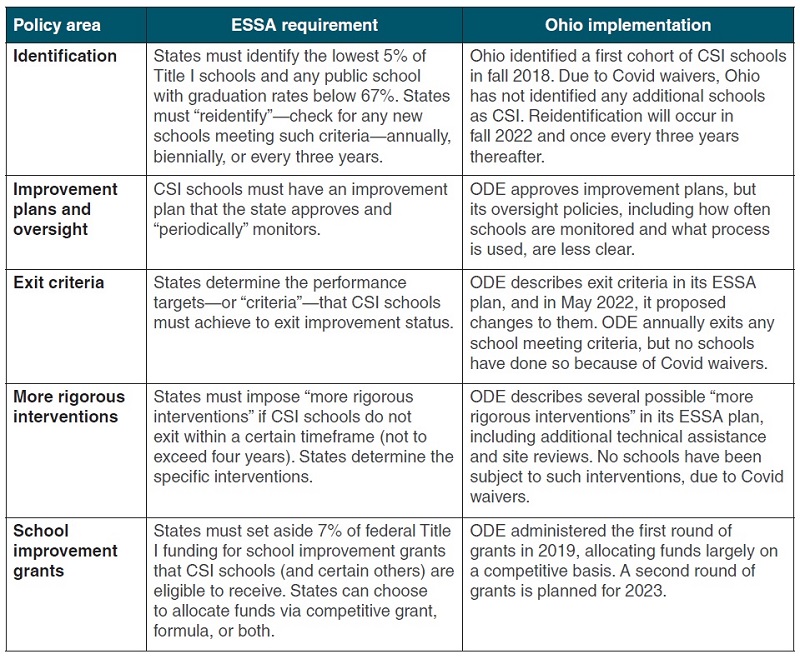

Under federal law, states must identify their lowest-performing schools as needing “comprehensive support and improvement” (CSI). Such schools are required to create improvement plans that the state must approve and monitor. Should a CSI school fail to meet states’ exit criteria within a certain timeframe, ESSA then requires states to determine “more rigorous interventions” for that school. CSI schools are eligible to receive federally funded school improvement grants—of somewhat modest amounts—which may be awarded by states via formula or a competitive process. Table 1 provides a high-level overview of the CSI program, including key federal requirements. It also briefly describes Ohio’s implementation, which is led by the Ohio Department of Education (ODE). More detail is found in the report starting here.

Table 1. Overview of the CSI program

In fall 2018, Ohio identified 285 underperforming CSI schools, of which about half were district and half charter. This is the first and only cohort of CSI schools to date. Because of paused accountability systems, no schools have exited, nor have any been added via reidentification. Though not a direct result of CSI policies, forty-one schools, including thirty-four charters, have closed, leaving 244 CSI schools open at the end of 2020–21. Taken together, these schools enrolled 112,000 students, roughly the size of the Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus school districts combined.

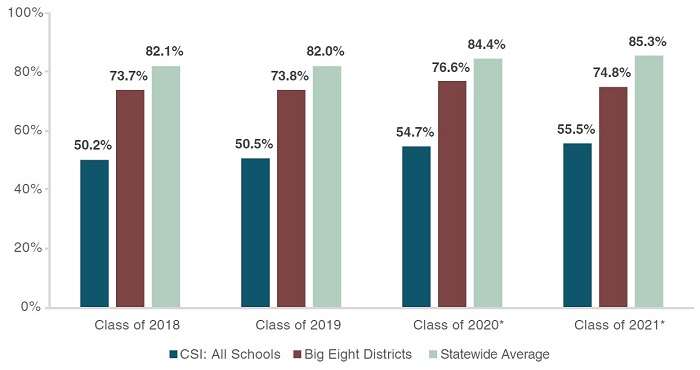

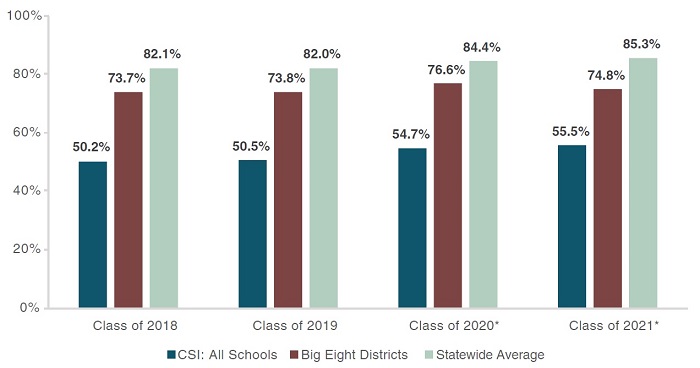

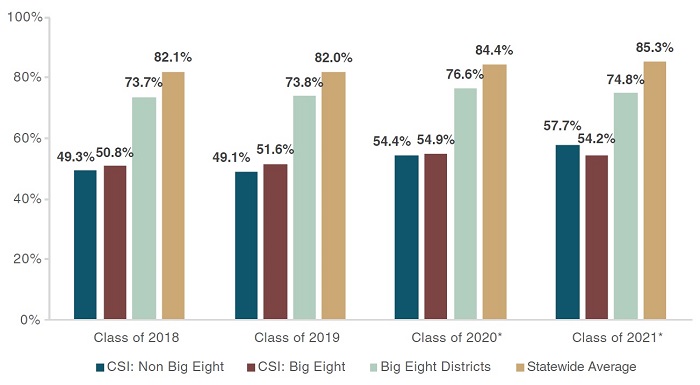

Though not surprising, data from 2017–18 to 2020–21 depict the academic troubles of Ohio’s CSI schools. For instance, figure 1 shows that in spring 2018—the year immediately prior to entering improvement status—just half of the students attending CSI high schools graduated on time. That rate was thirty-two percentage points below the statewide average and twenty-four points below the average of the Big Eight urban districts, where most CSI schools are located. In the three subsequent years—all years in which the schools were in improvement status—graduation rates rose by an average of 1.8 points per year. Despite the uptick, CSI schools’ graduation rates in 2021 remained thirty and nineteen points below the state and Big Eight averages, respectively.

Figure 1. CSI schools’ four-year graduation rates versus selected benchmarks

While the academic challenges are easily visible in the data, it’s less clear how exactly Ohio implements several crucial elements of its improvement program. For instance, as noted above, ESSA requires states to implement “more rigorous interventions” if CSI schools don’t meet exit criteria within a certain timeframe. But federal law doesn’t dictate specific interventions, leaving the decision to states. Without direction from the feds—or, as it turns out, from Ohio lawmakers—ODE determines them. In its ESSA implementation plan, the agency only hints at what might occur in this scenario, listing a half dozen options that it “may” require of schools, such as support from a regional educational service center, participation in a peer-to-peer network, or an on-site review. But how does ODE choose which item on the menu would apply to a school? Why might one CSI school get off the hook with a light consequence—seemingly no more than technical assistance—while another is subjected to an external review? Why aren’t more forceful actions a possibility, such as a wholesale restructuring of the school? Other hazy areas include how precisely ODE oversees and makes sure that CSI schools are following their improvement plans and whether schools are spending grants to implement highly effective, evidence-based practices.

To do right by students, Ohio’s school improvement program needs to involve more than a compliance routine and a few extra dollars. Indeed, research has shown that turnaround efforts are more likely to succeed when schools do more than nibble around the edges and instead fundamentally alter the way they operate.[6] But, while ODE has developed solid technical-assistance programs, Ohio’s ESSA-driven improvement program lacks the clarity and teeth needed to drive drastic changes in low-performing schools. To that end, state policymakers should develop a clearer, stronger, and more coherent school improvement program. This report outlines specific recommendations discussed in more detail starting here. To boil them down, they include the following:

- Ensure consistent, rigorous state oversight of low-performing CSI schools. Through its plan-approval process, ODE should insist that CSI schools’ plans include strong, evidence- based practices—e.g., curricula and materials that align with the science of reading in elementary grades, providing students with extended learning time, and policies that help to retain high-performing teachers (and remove ineffective ones). To ensure follow-through and to provide feedback on implementation, ODE should also strengthen its on-site inspection program, known as the school improvement diagnostic review (SIDR).

- Establish clear, forceful consequences for persistent school failure. ODE should develop concrete guidelines about what occurs if a school is required to undertake “more rigorous interventions.” If a school fails to respond to such interventions, the agency should require comprehensive restructuring, or work with the district or charter authorizer to close the school. More forceful accountability provisions are not only necessary for the interests of students but also to counterbalance incentives, via eligibility for improvement grants, to perpetually remain in CSI status.

- Drive more school improvement funds to CSI schools implementing effective practices. In its first (and, to date, only) cycle of competitive grants in 2019, Ohio spread dollars too thinly across hundreds of schools. In the next grant cycle, the state should award larger competitive grants to a smaller number of CSI schools that commit to intensive educational services and programs. For instance, larger awards could be offered to schools pledging to offer summer courses, high-dosage tutoring, or career-technical and work-based opportunities.

- Increase transparency about Ohio’s school improvement program. ODE should be more transparent about efforts to turn low-performing schools around. For instance, to aid public understanding, ODE should make improvement plans easily accessible to parents and local communities, and it should release a consolidated annual report about the progress of CSI schools.

Turning around troubled schools requires commitment and patience on the part of policymakers. It won’t win political accolades. The results may not materialize as quickly or as easily as hoped. But sitting on the sidelines as students receive an inadequate education isn’t an option, either. Creating sound policies for school-level improvement in Ohio—and sticking to them—would be a good start.

Introduction: From NCLB to ESSA

More than twenty years ago, in Hamilton, Ohio, President George W. Bush signed the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) act into law. Among the many policy reforms in that iteration of federal K–12 education law, NCLB required states to identify low-performing public schools and impose escalating consequences if they failed to meet performance benchmarks year after year. At the signing ceremony, President Bush offered his reasoning behind these provisions:

Every school has a job to do. And that’s to teach the basics and teach them well. If we want to make sure no child is left behind, every child must learn to read. And every child must learn to add and subtract. If, however, schools don’t perform, if, however, given the new resources, focused resources, they are unable to solve the problem of not educating their children, there must be real consequences.[7]

That logic is common sense. State leaders do have an obligation to intervene on behalf of children stuck in chronically failing schools, and cementing that concept into federal law was sensible. Despite the sound rationale and some evidence of improved achievement stemming from these accountability measures,[8] the policy drew fire for being excessively punitive and overly rigid. Congress overhauled the federal accountability framework through the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Although ESSA retains important NCLB provisions, such as annual state assessments and school report cards, it revamps school intervention requirements.

Reflecting shifts in thinking about federal-state relations in education, ESSA takes a more hands-off approach to school accountability. Although it requires states to engage in some form of improvement, what precisely that looks like is largely up to individual states. For instance, instead of federally prescribed interventions, ESSA outlines no specific consequences for poor performance. State policymakers, therefore, decide what types of programs and practices are acceptable in a school improvement plan, how exactly to oversee progress, and under what conditions low-performing schools may exit intervention (and what happens if they don’t).

This report first reviews, at a high level, federal school improvement policy under ESSA and how Ohio has implemented the law. Next, we analyze Ohio’s administration of federal school improvement grants under ESSA. Then, we examine Ohio’s first cohort of CSI schools, which comprise the lowest- performing schools in the state. The report concludes with recommendations that aim to strengthen the state’s school improvement policies.

We have three final introductory notes. First, ESSA focuses on improving individual schools rather than entire districts. In Ohio, ADCs have been a state-driven effort—not mandated under federal policy—to turn struggling districts around. Second, ESSA requires public charter schools to be included in a state’s accountability and improvement systems; nonpublic schools, however, are not. Third, ESSA—the current federal education law—is not to be confused with ESSER, which refers to the massive Covid-related funding packages for schools passed by Congress in 2020 and 2021.

Federal initiative and Ohio implementation

ESSA requires states to identify two separate groups of schools: CSI and “targeted support and improvement” (TSI).[9] CSI schools are the lowest-performing schools in the state, while TSI schools are less troubled yet fall short with specific groups of students (e.g., students with disabilities or English learners). States have greater responsibility in overseeing CSI schools, while local districts generally take the lead on TSI efforts. Because of the state’s smaller role in TSI schools, this report’s analysis of the category is brief.

A. Comprehensive Support and Improvement (CSI)

Per federal law, the overall CSI framework includes six key policy areas: (1) creating a state CSI plan, (2) identifying CSI schools, (3) creating and approving local school improvement plans, (4) monitoring plan implementation, (5) exiting CSI status, and (6) implementing “more rigorous interventions” if CSI schools don’t exit.[10]

Policy 1: Policymaking

ESSA requirements: State education agencies, after “meaningful consultation” with key stakeholders including the governor and legislature, must describe certain aspects of their school improvement policies in an ESSA plan that is approved by the U.S. Department of Education (USED). States can make amendments to their ESSA plans if they decide to alter their policies.

Ohio implementation: ODE drafted the state’s ESSA plan, which was approved by USED in early 2018.[11] Some portions of the plan simply reflected existing state law. For instance, Ohio statute has long included sections on assessments and school report cards, and those areas generally aligned with ESSA without needing revision.

In contrast, state law and regulation offer ODE little direction about how to structure a school improvement program under the more-flexible ESSA law. The current section of Ohio statute on school improvement is of no help, as it refers to NCLB-era policies such as “adequate yearly progress” (AYP) and the federally prescribed consequences for failing to meet AYP.[12] In yet another section of Ohio law, we find “restructuring” provisions—not tied to either NCLB or ESSA—that require district-run schools to either close, replace its principal and instructional staff, restart with a new operator, or convert to a charter school if they fail to meet certain performance criteria.[13] While forceful on its face, Ohio potentially relieves schools of these consequences if they conflict with federally driven interventions.[14] Meanwhile, the State Board of Education, the body that directly oversees ODE, hasn’t created specific rules about how the school improvement program is to function under ESSA. Instead, it generally refers readers to ODE’s ESSA plan.[15]

Absent clear state laws or regulations on school improvement, ODE—in a sense, by default—has significant authority to create and amend policy in this area. For instance, ESSA requires states, within certain parameters, to determine the frequency by which they identify CSI schools. ODE responded in its ESSA plan that Ohio would do so once every three years, thus making the policy without any formal legislation or rules being enacted. ODE also omits reference to the restructuring provisions in state law. Since those consequences aren’t incorporated into the ESSA plan, it’s possible that those may not be implemented. In fact, a clarifying rule created by the State Board of Education indicates that any school subject to Ohio’s restructuring law is instead deemed to be in CSI status.[16]

Policy 2: School identification

ESSA requirements: Under federal law, states must identify at least 5 percent of their Title I schools as CSI,[17] as well as any public high school—Title I or not—with four-year graduation rates below 67 percent. Each state must create a methodology to determine its lowest 5 percent (or more) of schools, with the state’s school rating system serving as the basis. States were required to unveil their initial lists of CSI schools by 2018. Thereafter, states can “reidentify”—add new schools meeting identification criteria—annually, biennially, or every three years.

Ohio implementation: To comply with ESSA provisions,[18] Ohio uses a modified “federal” graduation rate for the purposes of identifying schools with graduation rates below 67 percent. This calculation differs from the one reported on school report cards because it does not count students who receive diplomas by virtue of alternative requirements—largely students with individualized education plans (IEPs) as graduates. Appendix A has more detail about the federal versus state graduation-rate calculations.

Among Title I schools (and excluding high schools already identified under the graduation criteria), the lowest 5 percent in total points earned in Ohio’s overall school rating system are also identified as CSI.[19]

ODE opts to identify CSI schools once every three years, the longest duration allowed under federal law. Ohio’s first round of identification under ESSA guidelines occurred in fall 2018 and was based on data from the 2017–18 school year. Ohio identified 285 schools as CSI, including 144 charter schools, and more information about this first cohort is presented starting here. Ohio was initially scheduled to reidentify schools in fall 2021, but this was waived due to the pandemic. Instead, Ohio’s first reidentification of CSI schools will occur in fall 2022.

Policy 3: School improvement plans

ESSA requirements: Once a school is identified, the school district—in partnership with a school’s leaders, teachers, and parents—must develop an improvement plan for the school. The state education agency (SEA) is then required to approve a CSI school’s improvement plan. ESSA does not prescribe specific actions that must be included in such a plan (e.g., instructional reforms or staffing changes), but it does require a needs assessment and interventions that are “evidence based.” Although ESSA contains a definition of evidence based, the term is rather broad and allows for a wide range of activities.

Ohio implementation: CSI schools’ improvement plans are available through an online portal, known as CCIP.[21] The web interface is not user friendly, and among the various plans that districts and schools must submit, it is difficult to determine with certainty what precisely constitutes a CSI school’s improvement plan. The extent to which various stakeholders in a school participated in the development of the plan is also hard to ascertain, and it is unclear whether ODE requires—as it could through its approval authority—CSI schools to implement any specific programs or practices (e.g., insisting on high-quality curricula and materials or effective personnel practices). On the positive side, to support the use of evidence-based practices in improvement plans, ODE has developed a clearinghouse that allows users to search programs by grade band and subject area that schools could potentially use.[22] The online catalog is based on USED’s What Works Clearinghouse and a few other research organizations’ work that synthesizes various studies.

Policy 4: Plan implementation and oversight

ESSA requirements: States are responsible for monitoring and “periodically” reviewing the implementation of CSI schools’ plans. In addition, they must provide technical assistance to school districts with a “significant number” of CSI and TSI schools and conduct resource allocation reviews in such districts.[23] Beyond those basic guidelines, ESSA defers to states to decide how exactly to carry out these oversight responsibilities.

Ohio implementation: ODE has extensive technical-assistance resources that CSI schools can tap into. They include peer-to-peer networks, regional support systems, and the Ohio Improvement Process—a framework that schools may choose to use when developing an improvement plan.[24] ODE undertakes compliance-driven monitoring for federal programs.[25] More promisingly, in terms of providing active oversight and actionable feedback, ODE has developed a school improvement diagnostic review (SIDR). Though information about the program is limited, it appears to take a deeper dive into schools’ strengths and weaknesses through on-site visits.[26] It’s not clear how ODE determines which schools are selected for review or how many (if any) CSI schools have been reviewed under the SIDR program.[27] Unlike ODE’s district-level on-site reviews, which result in accessible reports, there are no known publicly available reports of the school-level SIDRs.[28]

Policy 5: Exit criteria

ESSA requirements: States must establish exit criteria that schools need to achieve to leave CSI status. However, the federal legislation does not set guidelines for those conditions. A state could implement weak exit criteria or set stringent ones that require substantial improvement for multiple years.

Ohio implementation: Ohio annually removes any CSI school that meets the state’s exit criteria, but because of Covid-related disruptions, no schools have actually exited. The exit criteria are in flux, as ODE proposed in May 2022 a significant revision to its original criteria in a draft amendment to its ESSA plan. If the amended criteria are approved by the feds, they would be as follows:[30]

When determining which schools are eligible to exit CSI status, each school’s improvement will be measured against its achievement level in the year that it was identified as a CSI school to ensure that the improvement is substantial and sustained. The exit criteria include the following:

- School performance is higher than the lowest 5 percent of schools based on the ranking of the Ohio School Report Card overall ratings for two consecutive years

- The school earns a federal graduation rate of better than 67 percent for two consecutive school years

- In the second year of meeting the two above criteria, the school also demonstrates improvement on their overall rating assigned on the Ohio School Report Cards.

ODE is right to require that CSI schools demonstrate “substantial and sustained” improvements to exit. The bulleted points, however, do not appear to reach such standards. The first two criteria ask CSI schools to do no more than avoid the identification criteria. The third, seemingly an effort to slightly raise the bar, is somewhat vague—whether it’s an improved rating versus the year of identification or year immediately prior is unclear—and it requires only one year of higher ratings (not a “sustained” improvement). In a May 2022 article, I suggested tweaks that would clarify the criteria, but it’s uncertain as of the writing of this report what exactly will happen with the exit criteria.[31]

Policy 6: More rigorous interventions

ESSA requirements: Federal law requires states to impose “more rigorous interventions” if CSI schools fail to meet a state’s exit criteria within a four-year (or less) timeframe. It does not, however, specify what these interventions shall be, so states decide how to implement the requirement.

Ohio implementation: In its original ESSA plan, ODE chose to implement more rigorous interventions if CSI schools failed to meet the exit criteria within four years, the maximum duration allowed under federal law. In a May 2022 draft amendment to the plan, the agency proposed reducing it to three years—a step in the right direction, especially if paired with strong intervention measures. Regardless of timetable, no school has been subject to these interventions. Starting in fall 2024 (or fall 2023, under the proposed revision), this would occur if there are schools identified in 2018 that haven’t met the exit criteria by then.

What does Ohio’s version of “more rigorous interventions” constitute? In its ESSA plan, ODE references six possible interventions that it may pursue in this situation. They include (1) supports from regional service providers, (2) peer-to-peer networks, (3) improvement reviews (seemingly akin to the SIDR process described above), (4) in-depth resource-allocation reviews, (5) more rigorous requirements on tiers of approved evidence-based strategies, and (6) required direct student supports. Few details are given about what exactly the potential interventions entail, and it’s not entirely clear how some of the options—such as participating in a peer-to-peer network—could be deemed an “intervention,” much less a “more rigorous” one. Little information is also given about how ODE decides which one of the options applies to a school. Why might one school receive a seemingly lighter consequence than another? Perhaps most surprising, given the issue, is that ODE’s plan omits reference to the state’s restructuring laws—discussed above—as potentially applying in these circumstances. That may or may not have been intentional, but the omission could make that section of state law moot.

B. Targeted Support and Improvement (TSI)

In addition to identifying CSI schools, ESSA also requires states to identify any school (Title I or not) that has one or more “consistently underperforming” student groups. The idea behind TSI is that some schools, while performing acceptably as a whole, could be struggling to serve specific groups of students (e.g., students with disabilities or who are economically disadvantaged). ESSA requires states to annually identify TSI schools, but once identified, ESSA requirements are limited. Under federal law, TSI schools must create improvement plans, but the state does not have to approve them. Unlike CSI schools, ESSA doesn’t require “more rigorous interventions” if TSI schools consistently fail to meet exit criteria.

ODE identified 537 schools for TSI status in fall 2018—roughly 15 percent of all Ohio schools. Due to their less-severe underperformance and the smaller role of the state in monitoring TSI schools, this report omits detailed analysis of schools in this category. However, because they are eligible for school improvement grants, TSI schools are included in that section.

C. Covid waivers

The pandemic and its widespread impacts interrupted the implementation of ESSA’s school intervention policies. In both spring 2020 and spring 2021,[32] the federal government offered states waivers from the requirement to identify new schools for CSI and TSI status. Save for a minor exception allowed by the feds, of which Ohio did not avail itself,[33] states were not permitted to exit schools from improvement status. As a result, Ohio’s initial list of CSI schools has been frozen for two years under the waiver program.[34]

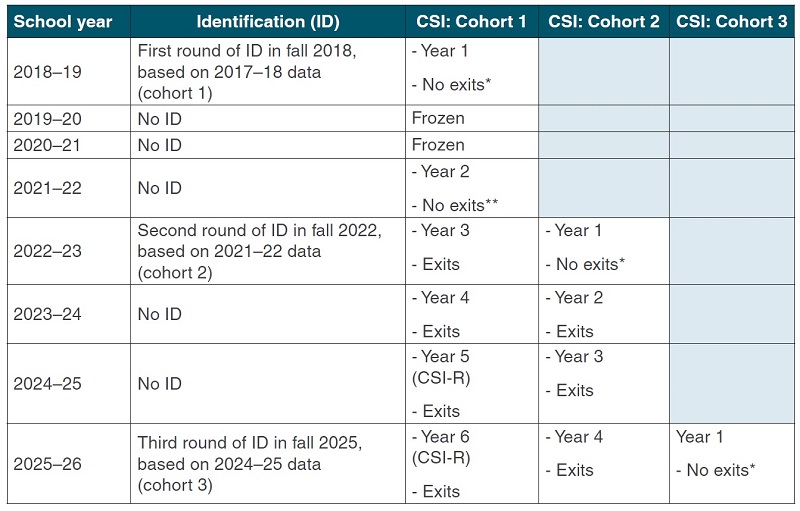

Based on results from the 2021–22 school year, all states—including Ohio—must restart CSI identification in fall 2022 and identify a second cohort of CSI schools. They’ll also be allowed to exit schools after the 2021–22 school year, though this is unlikely to apply in Ohio’s case.[35] Table 2 displays the timeline regarding CSI identification, the year of improvement (as it pertains to more rigorous interventions), and exiting possibilities after the school year.

Table 2. Timeline of Ohio’s CSI school actions under ESSA, 2018–19 through 2025–26

School quality improvement grants

ESSA requires states to set aside 7 percent of their Title I federal funding to support CSI and TSI schools. Of that amount, at least 95 percent must be allocated to schools via competitive grant or formula (or a mix of both). The remaining set-aside may be used by an SEA to implement the program and monitor and evaluate the uses of these funds. States must report the grant amounts that schools receive and the “types of strategies” that schools implement with these dollars. Awards may support program expenses over a maximum of four years, and schools can continue to spend grant funds even if they exit CSI or TSI status before expiration.

ODE calls this program the School Quality Improvement Grant (SQIG). In its first—and, to date, only—round of grant funding, the agency chose to allocate SQIG dollars first via competitive grant and disbursed remaining funds by formula to CSI and TSI schools that did not receive a competitive grant. The SQIG competition occurred in early 2019, shortly after the initial cohort of CSI and TSI schools were identified. The department’s application asked schools, among other things, to describe the activities and initiatives that the funds will support (Appendix C displays the template). Schools’ responses are available in an ODE database, but it’s hard to determine what grantees were required to do—outside of financial reporting—beyond their ESSA-required improvement plans.

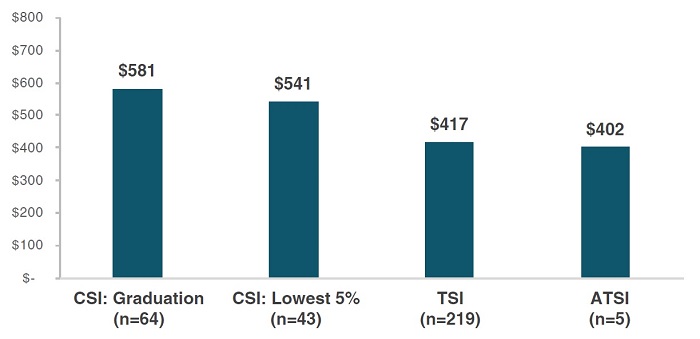

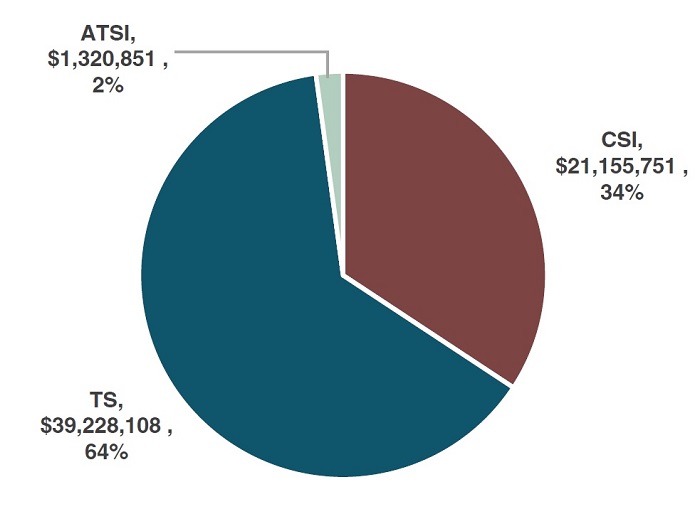

In the first cycle, 107 out of 285 CSI schools were awarded competitive grants (38 percent of them), as were 225 out of 537 TSI schools (42 percent).[36] ESSA does not set minimum or maximum grant awards, but ODE created guidelines that provide somewhat larger grants to CSI schools and those with higher enrollments (the funding framework appears in Appendix D). Roughly three-quarters of the Title I set-aside was distributed via competitive grant, with a smaller share allocated by formula. That reflects the size of the competitive awards, with the average grant being worth roughly $450 per pupil annually versus $50 per pupil for noncompetitive grants.[37] Figure 2 displays the average grant per pupil by intervention status, showing that CSI schools receive about $150 more per-pupil funding than TSI schools.

Figure 2. Average per-pupil amount of schools’ SQIG competitive grant by intervention status, FY 2021

Despite their smaller per-pupil grant amounts, the next chart shows that TSI schools receive a larger portion of the overall competitive SQIG dollars. That reflects the higher number of schools that received grants—as noted above, 225 TSI schools won awards versus just 107 CSI schools. Although there are more TSI schools overall, it’s somewhat surprising to see the modest portion of the set- aside going to CSI schools. As the tables in Appendix B demonstrate, CSI schools are—as one might expect—more academically challenged, and they also enroll more disadvantaged students.

Figure 3. Distribution of competitive SQIG funds by intervention status in FY 2021

A second round of SQIG funding is planned for 2023, which will also allow Ohio’s second cohort of CSI and TSI schools to apply. Continuing to allocate the bulk of SQIG funds competitively holds more promise than simply sending money to low-performing schools with no strings attached. It encourages schools to be more thoughtful about how these dollars are being used and to commit, on paper at least, to effective practices. But the extent to which ODE demands more from schools in return for the grant dollars and how it oversees spending remains an open question. There is, for example, no accessible report that provides basic information about SQIG, including documentation about the “types of strategies” schools use to improve student achievement. Moreover, spreading funds to so many schools, including hundreds of less-troubled TSI schools, means that CSI schools may not have the extra resources needed to effectively implement rigorous and potentially costly interventions.

High-dosage tutoring, for example, is estimated to cost more than $1,000 per pupil.[38] Under the now-defunct SIG program, which produced positive academic impacts in Ohio, the state awarded improvement grants worth about $2,000 per pupil.[39] As ODE plans future rounds of SQIG funding, it should consider mechanisms that drive more competitive grant dollars to CSI schools and ensure that the schools put these dollars to good use.

Analysis of Ohio’s CSI schools

In fall 2018, ODE identified 285 schools—8 percent of public schools in the state—as CSI, roughly half of which were district-run schools and the other half public charter schools. By October 2021, forty-one CSI schools had closed: thirty-four were charters, and seven were operated by a traditional school district (five of which were Cleveland). The comparatively high number of charter closures likely reflects reforms enacted in 2015 that strengthened charter accountability, particularly for sponsors (or “authorizers”). These governing entities have the authority to close a charter school because of poor academic performance and, likely in response to policy incentives, have more aggressively closed underperforming schools in recent years.[40] Although permanent closures can be challenging, research indicates that students who move from low-performing schools to superior ones after closure reap academic benefits.[41]

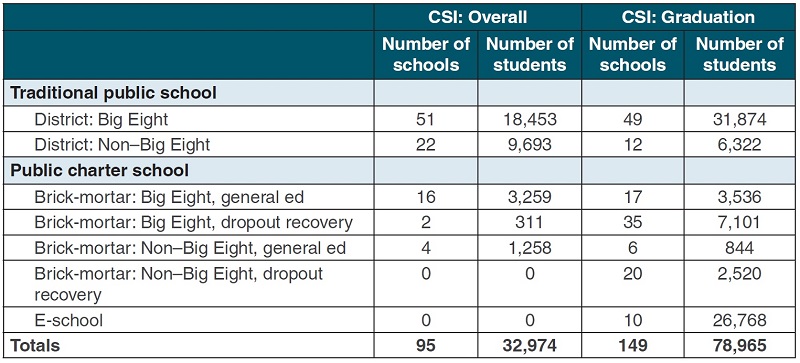

That leaves 244 schools from the first CSI cohort open today. Of those schools, 95 were identified on the basis of low overall scores in 2017–18; this paper refers to those schools as CSI: Overall. Another 149 schools were identified because of low graduation rates (CSI: Graduation). As Table 3 shows, these schools together enrolled almost 112,000 students in 2020–21—or 7 percent of all Ohio public school students. Most CSI schools are located in the Big Eight, cities that have historically struggled with low academic performance. Of the 244 CSI schools open today, 170 are located in the Big Eight (a hundred district and seventy charter schools). The schools represent 24 percent of all public schools in these cities, a much higher fraction than the 3 percent of non–Big Eight schools that are identified as CSI. Given their locations in urban areas, CSI schools enroll more Black and Hispanic students compared to the statewide average and serve almost double the percentage of economically disadvantaged students (Appendix Table B1). Cleveland and Columbus have the most CSI schools of the Big Eight cities (Appendix Tables B2–B3).

Table 3. Summary of CSI schools, 2020–21

Table 3 highlights a couple nuances regarding charter schools that are identified as CSI. First, more than half of CSI charters are designated by the state as “dropout-recovery” schools because they educate primarily students who have dropped out or are at-risk of doing so. Dropout-recovery schools, as one might expect, typically register extremely low four-year graduation rates. Second, ten e-school charters are identified as CSI, among which is the state’s largest e-school, Ohio Virtual Academy, which enrolled roughly 18,000 students in 2020–21.

Academic data

The pandemic impacted the data available to examine performance trends in CSI schools. State tests were cancelled in spring 2020. Results from spring 2021 assessments revealed significant learning losses across Ohio and nationally; in addition, fewer students participated in state exams than in a typical year. As a result of these challenges, Ohio released only limited data for the 2019–20 and 2020–21 school years. No overall or component ratings were assigned in these years, nor are there school-level data on student academic growth (i.e., value-added results). However, the overall and value-added ratings of CSI schools for the 2017–18 and 2018–19 school years appear in Appendix Table B4. As one might expect, the ratings are low.[42]

Caveats and all, it’s worth digging into the extant data to get a sense of the baseline performance of CSI schools and their short-term trends since identification. This section reviews performance-index (PI) scores and graduation rates from the 244 CSI schools that remain in operation. Their results are compared to two benchmarks—Big Eight district and statewide averages. The Big Eight is a useful comparison, as most CSI schools are located in those cities and the demographics of CSI schools are broadly similar. Although it’s a tall order for CSI schools to match statewide averages, performance against this benchmark helps us gauge results versus overall trends.

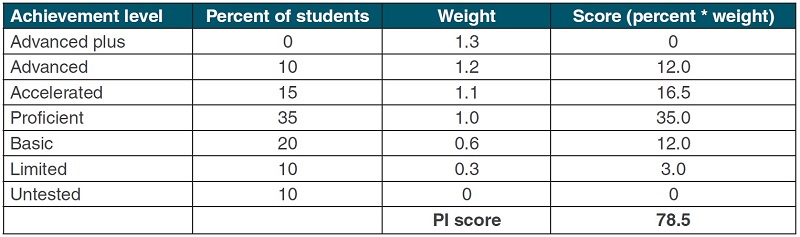

Performance index

Ohio’s PI is a composite measure of student achievement across all Ohio exams. As the table below shows, the measure provides extra weight to schools when students earn higher scores. Nonparticipation in state testing generates zeros on the measure. This policy usually has minimal impact on PI scores, but in 2020–21, the percentage of untested students was higher than usual, particularly in urban areas. In the year prior to the pandemic, the statewide average PI score was 85, but due to learning losses and nonparticipation in state testing, that average fell to 73 in 2020–21.

Because of test cancellations in spring 2020, no PI scores were reported for 2019–20.

Table 4. How the PI is calculated

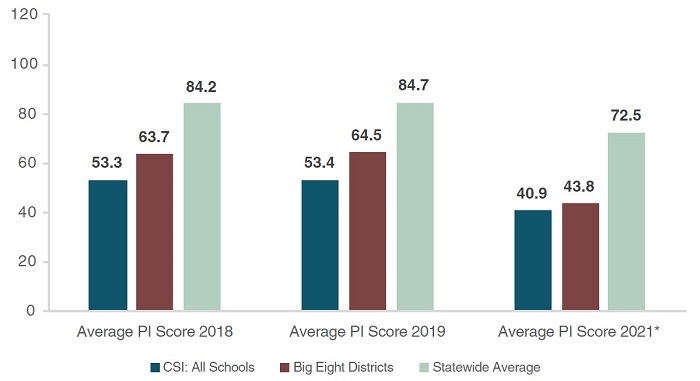

Not surprisingly, given the identification rules, CSI schools register very low PI scores. In 2017–18— the year of data that led to identification—their average PI score fell ten points below the Big Eight district average and was more than thirty points lower than the statewide average. Scores such as these indicate that most students in CSI schools have academic deficiencies. Indeed, just 27 percent of CSI schools’ third graders achieved proficiency on the state ELA exam in 2017–18, and 16 percent of high school students attending CSI schools reached that mark on the Algebra I exam.

The average PI score across CSI schools inched up by 0.1 points in 2018–19—the first year of improvement status—but that gain was less than the Big Eight districts (0.8 points) and fell short of the statewide gain (0.5 points). At the far right of Figure 4, we see that PI scores dropped sharply in the Big Eight districts in 2020–21, declining by 20.7 points relative to 2018–19. Achievement losses compared to 2018–19 were also large in CSI schools (−12.5 points) but tracked more closely with the change in the statewide average (−12.2 points) than the Big Eight average.

Figure 4. CSI schools’ PI scores versus selected benchmarks, 2017–18 to 2020–21

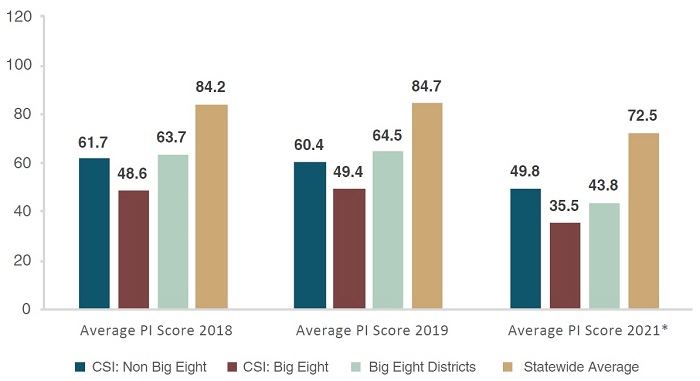

Though most CSI schools are in the Big Eight, about 30 percent are located outside of those cities. Figure 5 indicates that non–Big Eight CSI schools have noticeably higher PI scores than their Big Eight CSI counterparts. In 2017–18, non–Big Eight CSI schools scores were 13.1 points higher than Big Eight CSI schools. That margin increased by 2020–21 to 14.3 points, as non–Big Eight CSI schools’ scores dipped less than their Big Eight counterparts.

Figure 5. CSI schools’ PI scores by Big Eight and non–Big Eight location, 2017–18 to 2020–21

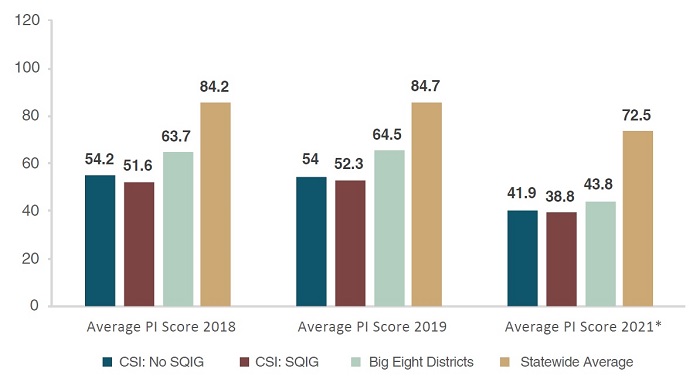

Figure 6 shows that CSI schools receiving competitive SQIG grants have trailed other CSI schools by one to three points. SQIG schools lost slightly more ground on this measure than non-SQIG, CSI schools between 2017–18 and 2020–21 (−12.8 versus −12.3 points).

Figure 6. PI scores by SQIG funding status, 2017–18 to 2020–21

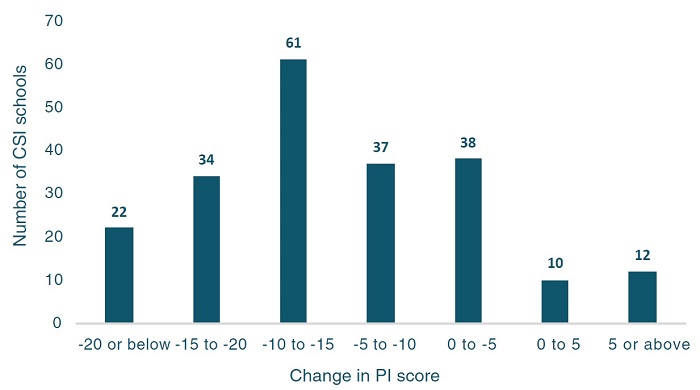

The averages mask variation in performance across individual CSI schools. Figure 7 shows that twenty-two CSI schools increased their PI scores between 2017–18 and 2020–21. But on the balance, consistent with pandemic-related losses in scores statewide, most CSI schools lost ground on this measure. Seventy-five CSI schools posted somewhat modest declines of zero to ten points, while over a hundred schools suffered dips larger than ten points. The practices of CSI schools that have posted improvements during this period could warrant further exploration in future research, as they may provide models for other schools.

Figure 7. Change in PI scores across CSI schools, 2017–18 to 2020–21

Graduation rates

We last examine four-year graduation rates, using the federally compliant rates used for CSI identification, which is different from the “state” graduation rate that appears on report cards (see Appendix A). Although there are continuous data on graduation from 2017-18 to 2020-21, rates have also been affected by the pandemic, as Ohio legislators allowed schools to award diplomas to certain students in the classes of 2020 and 2021 even if they hadn’t met standard requirements.[43] The temporarily lowered bar likely boosted graduation rates, possibly more so in lower-performing schools with more off-track students.

Figure 8 begins by showing the four-year graduation rates for the classes 2018–21. At a baseline, CSI schools posted a 50.2 percent graduation rate for the class of 2018, a number that is substantially below the Big Eight district and statewide average. Keep in mind that, as mentioned earlier, dozens of the CSI schools are “dropout-recovery” schools, and these are dragging down the averages. Since 2018, CSI schools’ graduation rates have increased by 5.3 percentage points to 55.5 percent for the class of 2021. The gap, however, between the statewide and Big Eight averages remain very large. CSI schools’ graduation rates for the class of 2021 fell thirty and nineteen percentage points below the state and Big Eight averages, respectively.

Figure 8. CSI schools’ four-year graduation rates versus selected benchmarks, class of 2018 to 2021

The next figure shows that overall improvements in graduation rates are due more to non–Big Eight schools. CSI schools located outside of the Big Eight registered graduation rate improvements of 8.4 versus 3.4 percentage points for CSI schools in the Big Eight.

Figure 9. CSI schools’ four-year graduation rates by Big Eight and non–Big Eight location, class of 2018 to 2021

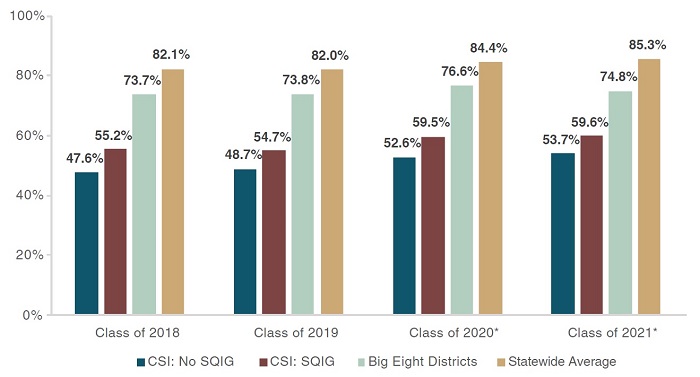

Figure 10 displays average graduation rates based on whether CSI schools received competitive SQIG funding. In contrast to the PI results, SQIG-funded CSI schools post higher four-year graduation rates than non-SQIG schools. That said, non-SQIG schools made greater improvements in graduation rates from 2018 to 2021—a 6.1 percentage point gain—than their SQIG counterparts (4.4 points).

Figure 10. Four-year graduation rates by SQIG funding status, class of 2018 to 2021

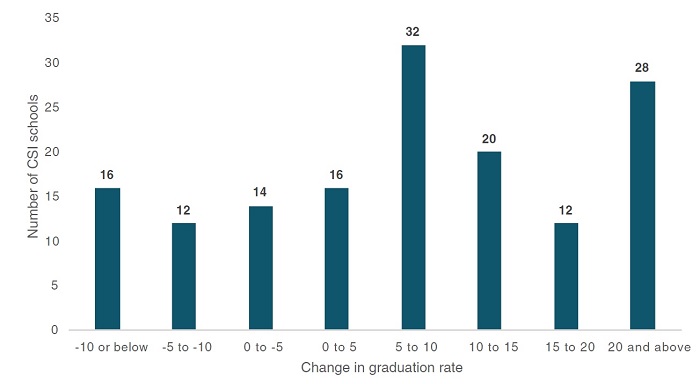

Akin to the changes in PI scores, wide variation emerges when looking at changes in graduation rates across CSI schools. On one end of the spectrum, twenty-eight CSI schools’ graduation rates increased by a whopping twenty percentage points or more, but another forty-two schools registered declines.

Figure 11. Change in four-year graduation rates among CSI schools, class of 2018 to 2021

Overall, for various reasons, we cannot reach definitive conclusions about whether CSI schools as a whole got better during this turbulent period in education. As data come in for the 2021–22 school year and beyond, policymakers should keep tabs on the trends in CSI schools; a rigorous evaluation of the program’s effectiveness would certainly be welcome, as well. However, what is clear from this overview is that the academic results of CSI schools remain low, and significant work is required to improve their outcomes.

Policy recommendations

Trying to turn around troubled schools remains a moral imperative and federal requirement for Ohio policymakers. But fulfilling these obligations will take more than completing compliance checks and sending dollars to schools. Ohio policymakers still have their work cut out in terms of devising a strong, clear school improvement program. We offer several recommendations to that end. Note that ODE could likely undertake all these actions without legislative action, but the General Assembly should consider incorporating them into a comprehensive package that updates Ohio’s school improvement statutes. Codifying school improvement policies would better ensure faithful ODE implementation, even if its leadership and priorities change.

- Recommendation 1: ODE should display a notice on a school’s report card if it is in CSI status and include a link to its improvement plan. Though school report cards include parent-friendly ratings, they omit any notice that a school has been identified under federal law as low performing. School improvement plans, meanwhile, are virtually impossible to find. Putting a notice on the report card would better inform the public that a school requires intervention, and linking to its improvement plan would allow parents and communities to see the promises a school has made—and allow them to hold the school accountable for fulfilling them.

- Recommendation 2: ODE should use its plan-approval authority to insist on high- quality practices, materials, and programs in CSI schools. ESSA requires SEAs to review and approve CSI schools’ improvement plans. While ODE almost surely has a formal process for reviewing plans, it should more explicitly and transparently set expectations about what should be in a plan. In elementary grades, for instance, the agency should require CSI schools to disclose their literacy strategies and should only approve plans that align with the science of reading.[44] In high school, the department could make sure that schools, particularly those that are identified for low graduation rates, provide extended learning time and academic or career supports.

- Recommendation 3: ODE should conduct biennial site visits in CSI schools that provide feedback on leadership and instructional practices, with a report made publicly available. For CSI schools subject to more rigorous interventions, visits should occur annually. On-the-ground engagement can surface problems that can’t be seen from desk reviews, offer more valuable and actionable feedback, facilitate connections between schools and support networks, and even uncover opportunities for the state to interject on behalf of an individual school to remove administrative barriers.[45] ODE already has experience conducting site visits through its SIDR, and it does in-depth reviews of a small number of struggling districts each year. It’s unclear, however, how often these evaluations occur in CSI schools, what type of feedback they offer, and whether there is any follow-up regarding whether schools put into practice observers’ recommendations. State policymakers should ensure that on-site evaluations in CSI schools occur at least every two years—and each year for those in more rigorous intervention—and make the findings publicly accessible. In-depth inspections in schools may require additional ODE capacity—they are not inexpensive—and legislators should consider allocating additional state funds for this purpose.[46]

- Recommendation 4: ODE should require CSI schools subject to more rigorous interventions to implement practices that have the strongest evidence of effectiveness. The department’s ESSA plan offers only vague descriptions about how it intends to implement more rigorous interventions when CSI schools fail to exit. With assistance from researchers and practitioners, ODE should create a short list of reforms from which CSI schools subject to more rigorous interventions must select. Those might include approaches such as prescribing specific high-quality curricula and materials, a rigorous teacher-feedback and coaching system, career-technical programs, or high-dosage tutoring and/or quality summer opportunities for students.[47]

- Recommendation 5: If CSI schools continue to fail, ODE should require the school to significantly restructure or close. In cases of persistent failure—e.g., starting in year seven or eight of CSI status—ODE should require more forceful restructuring, such as requiring staffing changes, “restarting” the school with a proven operator, or working with a district or authorizer to close the school. (State lawmakers could also modify the state’s existing, though perhaps irrelevant, restructuring law to make such interventions applicable when CSI schools fail to exit after many years.) As a matter of principle, flexibility and local autonomy should be respected, but after too many years of failure, the state should impose stricter requirements in students’ best interests. Heightened accountability measures are also critical to balancing the perverse incentive for a school to remain in CSI status simply to maintain eligibility for SQIG funds.

- Recommendation 6: ODE should dedicate up front a larger portion of SQIG funds for CSI schools and provide larger competitive grants to those committed to implementing effective practices. While other pools of funding can be used to support turnaround efforts—including substantial Covid-relief dollars—the relatively small sizes of these grants may be insufficient for schools considering whole-school reforms or time- or labor-intensive interventions. To ensure that CSI schools have adequate resources to undertake substantial changes, ODE should dedicate more funds up front for CSI schools in the next round of SQIG (e.g., two-thirds of the Title I set-aside). ODE should also offer higher maximum grant awards to CSI schools that commit to practices that meet the highest (“level 1”) evidence standard in their funding application. It also goes without saying that ODE should carefully follow ESSA provisions that require states to “monitor and evaluate” the uses of these funds.

- Recommendation 7: ODE should disclose in an accessible format each school’s SQIG award and the uses of those funds. The state report cards issued in 2018–19 to 2020–21 did not report SQIG funding, nor is there an accessible downloadable file on ODE’s website that contains information about SQIG grants. To find information about SQIG funding, one must navigate the complicated CCIP data portal. All this limits public transparency about the allocation and uses of these funds and appears to be inconsistent with ESSA reporting requirements.[48]

- Recommendation 8: ODE should release an annual publication that summarizes its school improvement efforts and the academic progress of CSI schools. There is no consolidated report on Ohio’s improvement efforts and the academic performance of CSI schools. As a matter of basic transparency, that should change. Lawmakers could go one step further and insist that the report findings be presented annually in the education committees to draw attention to the program and promote a better understanding of it.

Under ESSA, federal lawmakers have given states the ability to chart their own course when it comes to fixing low-performing schools. Shifting authority—and responsibility—to state policymakers is sensible. They are closer to the problem than D.C. bureaucrats and can tailor solutions to local contexts. But state leaders can’t put school improvement on autopilot and hope for the best. It won’t be for the faint of heart, but with strong leadership and thoughtful policymaking, school improvement has the potential to create brighter futures for more Ohio students.

Abbreviations and glossary

Academic distress commission (ADC): This is a state-driven initiative that increases state oversight of low-performing districts through an appointed five-member commission whose members supervise the district and a chief executive officer charged with creating and implementing a district-wide improvement plan. At the time of this report, ADCs oversee three Ohio districts: East Cleveland, Lorain, and Youngstown.

Big Eight: The Big Eight consist of Ohio’s largest urban school districts: Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown.

Comprehensive support and improvement (CSI): Under ESSA, states must identify low-performing schools as being in CSI status. In this report, CSI: Overall refers to schools identified based on their overall scores being within the lowest 5 percent of Ohio’s Title I schools, while CSI: Graduation refers to high schools identified because their graduation rates are below 67 percent. In Ohio, CSI schools are also known as “priority” schools.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA): Enacted in December 2015, this is the main federal K–12 education law. It includes Title I funding—extra federal dollars to support high-poverty schools—along with state assessment, report card, and school improvement requirements. ESSA is the current iteration of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, the previous version being No Child Left Behind (NCLB).

Performance index (PI): Ohio’s composite measure of student achievement across all state tests. It provides more weight, or “credit,” when students score at higher achievement levels (the calculation is illustrated here). PI scores have appeared on Ohio’s school report cards since at least 2003 and are a major component of the overall rating system.

State education agency (SEA): A government agency that oversees a state’s K–12 education system and implements federal and state education policies. The Ohio Department of Education (ODE) is Ohio’s state education agency.

School quality improvement grant (SQIG): The name of Ohio’s grant program that allocates federal school improvement funds to CSI and TSI schools. ESSA requires states to set aside 7 percent of Title I funding for this purpose; states may choose to distribute these dollars to schools via formula, competitive grant, or a mix of both.

Targeted support and improvement (TSI): Under ESSA, states must identify schools as TSI that have one or more low-performing subgroup of students (e.g., students with disabilities or English learners). In Ohio, schools in this category are also known as “focus” schools.

About this Report

About Fordham

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute promotes educational excellence for every child in America via quality research, analysis, and commentary, as well as advocacy and charter school authorizing in Ohio. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, and this publication is a joint project of the Foundation and the Institute. The Institute is neither connected with nor sponsored by Fordham University.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the many individuals whose time and talents helped to shape this report. On the Fordham side, I thank my colleagues Michael J. Petrilli, Chester E. Finn, Jr., Chad L. Aldis, and Jessica Poiner for their insightful feedback on earlier drafts of the report. Fordham’s Jeff Murray provided expert support managing report publication and dissemination. Special thanks to Stéphane Lavertu of The Ohio State University for his terrific feedback on the report. Pamela Tatz copy edited the report, and Andy Kittles created the report design. All errors, however, are my own.

Aaron Churchill

Ohio Research Director, Thomas B. Fordham Institute

Endnotes

[1] Patrick O’Donnell, “New state ‘takeover’ plan would start intervention early for schools with F grades,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 12, 2019.

[2] Andy Smarick, “The turnaround fallacy,” Education Next 10, no. 1 (2009).

[3] For studies indicating gains for displaced students who transition to higher-performing schools after a school closing, see Whitney Bross, Douglas Harris, and Lihan Liu, The Effects of Performance-Based School Closure and Charter Takeover on Student Performance (New Orleans, LA: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans, 2016), and Deven Carlson and Stéphane Lavertu, School Closures and Student Achievement: An Analysis of Ohio’s Urban District and Charter Schools (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2015).

[4] For a scholarly review of the school-level improvement literature, see Beth E. Schueler, et. al., “Improving Low-Performing Schools: A Meta-Analysis of Impact Evaluation Studies” (EdWorking Paper No. 20-274, Annenberg Institute at Brown University, August 2020). For a shorter piece discussing the research, see Jill Barshay, “PROOF POINTS: A turnaround on school turnarounds,” The Hechinger Report, September 21, 2020.

[5] Daniel Player and Veronica Katz, “Assessing School Turnaround: Evidence from Ohio,” The Elementary School Journal 116, no. 4 (2016), and Deven Carlson and Stéphane Lavertu, “School Improvement Grants in Ohio: Effects on Student Achievement and School Administration,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 40, no. 3 (2018).

[6] In “Improving Low-Performing Schools,” Schueler, et al., find that replacing teachers and extending learning time were the initiatives most strongly associated with learning gains in evaluations of school improvement programs across the United States. Less impactful were activities such as professional development, data usage, and replacing principals. In “School Improvement Grants in Ohio,” Carlson and Lavertu find that low-performing Ohio schools undertaking the more intensive “turnaround” model from 2009–12 posted stronger gains than those using a lighter-touch “transformation” model.

[7] “President Signs Landmark No Child Left Behind Education Bill,” The White House, January 8, 2002.

[8] Thomas Dee and Brian Jacob, “The Impact of No Child Left Behind on Student Achievement” (working paper 15531, National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2009).

[9] ESSA requires states to identify a third category of schools: “additional targeted support and improvement” (ATSI). Because of the added complexity of this policy and the fact that Ohio identifies so few ATSI schools—just eleven in fall 2018—discussion of this category is omitted.

[10] The following descriptions of ESSA requirements are drawn from the bill text, available at “Every Student Succeeds Act,” Public Law 114–95—December 10, 2015; Congressional Research Service, The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as Amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA): A Primer (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, August 2020); and Council of Chief State School Officers, School & District Improvement FAQs, Topic 1: Identification of Schools (Washington, D.C.: Council of Chief State School Officers, 2016).

[11] Ohio Department of Education, Revised State Template for the Consolidated State Plan (Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Education, January 2018).

[13] Consequences are triggered when a school, for three consecutive years, is in the bottom 5 percent statewide in PI scores and receives a one-star value-added rating or a one- or two-star overall rating. The law went into effect in 2013–14, but due to pauses in accountability related to testing transitions and Covid, it’s unlikely that any school has been required to restructure. See Ohio Revised Code 3302.12.

[14] Ohio Revised Code 3302.12(C), reads as follows: “If the provisions of this section [on restructuring] conflict in any way with the requirements of federal law, federal law shall prevail over the provisions of this section.”

[15] State Board of Education rules on school improvement are at Ohio Administrative Code 3301-56-01.

[16] Ohio Administrative Code 3301-56-01(A)(2).

[17] “Title I schools” are public schools that receive federal Title I funding under ESSA. About three in four Ohio public schools are Title I schools; see Common Core of Data, “Table 3. Number of operating public elementary and secondary schools, by school type, charter, magnet, Title I, Title I schoolwide status, and state or jurisdiction: School year 2019–20,” National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, accessed July 22, 2022.

[18] With an exception for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities, ESSA requires states to only count students as graduates who earn a “regular high school diploma,” which is defined as “the standard high school diploma awarded to the preponderance of students in the State that is fully aligned with State standards.”

[19] For more details about Ohio’s school rating system, including overall rating calculations, as implemented in 2017–18, see Ohio Department of Education, Appendix B: ESSA Sections A.1-A.4: (Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Education). Although no overall ratings will appear on report cards issued for 2021–22, overall scores will be calculated for the purposes of ESSA identification. The calculations will be different than those used in 2018 due to recent report card reforms passed in House Bill 82 of the 134th General Assembly; House Bill 82.

[20] Institute of Education Sciences, “What is ‘evidence-based’ as defined by the Every Student Succeeds Act?”. Evidence-based practices are also required or encouraged in other areas of ESSA (beyond school improvement). See Results for America, “The Evidence Provisions of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)”.

[21] “CCIP,” Ohio Department of Education, accessed June 3, 2022. The state is currently transitioning to a new platform called ED STEPS. “ED STEPS,” Ohio Department of Education, accessed June 3, 2022.

[22] “Ohio’s Evidence-Based Clearinghouse,” Ohio Department of Education, accessed June 3, 2022.

[23] For more on the ESSA resource allocation provision, see Education Trust, “Resource Allocation Reviews: A Critical Step to School Improvement” (paper, Education Trust), accessed July 21, 2022.

[24] For more on Ohio’s technical assistance and school improvement supports, see Ohio Department of Education, Revised State Template for the Consolidated State Plan, and “Collaboration to Put Students First: Ohio’s Collaborative School Improvement Model,” ESSA Implementation Lessons Learned: Blog 3, Office of Elementary & Secondary Education, U.S. Department of Education, January 14, 2022.

[25] Ohio Department of Education, Consolidated ESEA Grants On-Site and Desk Review Monitoring and Tracking System User Manual (Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Education, 2020).

[26] “Diagnostic Review,” Ohio Department of Education, accessed June 3, 2022, https://education.ohio.gov/Topics/District- and-School-Continuous-Improvement/Diagnostic-Review.

[27] In 2018–19 and 2019–20, ODE reports that a total of twenty-five schools, some of which may have been CSI, were reviewed under the SIDR program. “Request for Proposals: Improvement Review Services 2022,” Ohio Department of Education, accessed July 21, 2022.

[28] “District Reviews,” Ohio Department of Education, accessed June 3, 2022.

[29] This description is based on materials available via “Monitoring Site Visits (MSVs) and Targeted Site Visits (TSVs),” Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), accessed April 29, 2022. For an analysis of the program, see Susan Bowles Therriault, Jill Walston, Yibing Li, and Jingtong Pan, Relationships between Schoolwide Instructional Observation Scores and Student Academic Achievement and Growth in Low-Performing Schools in Massachusetts, REL 2020–026 (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, 2021).

[30] The original exit criteria and proposed amended language is available at Ohio Department of Education, Revised State Template for the Consolidated State Plan.

[31] Aaron Churchill, “ODE should rework its exit criteria, again,” Ohio Gadfly Daily, Thomas B. Fordham Institute, June 27, 2022.

[32] Guidance for the 2020–21 school year is available at U.S. Department of Education, Frequently Asked Questions: Impact of COVID-19 on Accountability Systems Required under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, January 2021).

[33] Based on 2020–21 graduation rate data, states could remove CSI schools identified under the low graduation rate provision if they met the state’s exit criteria. In a March 2021 memo, ODE stated that it would not allow any schools to exit CSI status (even if they met the graduation exit criteria); see “Memo: Submission of New Waiver Request for Select Accountability Requirements of Ohio’s Every Student Succeeds Act Plan” (Ohio Department of Education, Columbus, OH, March 2021).

[34] The 2020 and 2021 waivers from the federal government allowed states to “hold harmless” CSI schools—i.e., not count the 2019–20 and 2020–21 school years against them before more rigorous interventions apply.

[35] Guidance for the 2021–22 school year is available at U.S. Department of Education, Frequently Asked Questions: Impact of COVID-19 on 2021–22 Accountability Systems Required under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA) (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, February 2022).

[36] Though no grant amounts are reported, the list of schools receiving SQIG funding is posted at this website. Five of the eleven ATSI schools received competitive SQIG funds. Another eight schools received grants yet do not appear on the CSI, TSI, or ATSI lists; they may have been eligible through an exemption related to the former SIG program.

[37] In FY 2022, ODE sent $10.5 million in competitive SQIG funds to CSI and TSI schools, which together enrolled about 215,000 students in 2020–21. See Ohio Department of Education, Non-Competitive, Supplemental School Improvement Grant Funding Guidance (Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Education, 2021).

[38] Matthew Kraft and Grace Falken, “A Blueprint for Scaling Tutoring Across Public Schools,” (EdWorking Paper No. 20-335, Annenberg Institute at Brown University, January 2021).

[39] Carlson and Lavertu, “School Improvement Grants in Ohio.”

[40] For more on Ohio’s charter reforms, see Aaron Churchill, Jamie Davies O’Leary, and Chad L. Aldis, On the Right Track: Ohio’s charter reforms one year into implementation (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2017).

[41] Bross, Harris, and Liu, The Effects of Performance-Based School Closure, and Carlson and Lavertu, School Closures and Student Achievement.

[42] The value-added ratings for 2017–18 and 2018–19 were calculated based on three-year averages. The multiyear averaging helps to avoid large swings in ratings (e.g., moving from an A to F or vice versa), but it makes it difficult to observe short-term improvements through the rating system.

[43] The graduation waivers were passed via House Bill 197 of the 133rd General Assembly for the class of 2020 and House Bill 67 of the 134th General Assembly for the class of 2021.

[44] For more on the science of reading, see for example, Louisa C. Moats, “Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science: What Expert Teachers of Reading Should Know and Be Able to Do,” American Educator 44, no. 2 (Summer 2020): 4–9. ODE’s statewide literacy plan emphasizes the importance of instruction aligned to the science of reading. Ohio Department of Education, Ohio’s Plan to Raise Literacy Achievement (Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Education, January 2020).

[45] ESSA allows states, “as appropriate,” to reduce barriers and provide operational flexibility to CSI or TSI schools.

[46] Ashley Berner, Would School Inspections Work in the United States? (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins School of Education, Institute for Education Policy, September 2017).

[47] For evidence on high-quality textbooks, see Corey Koedel and Morgan Polikoff, Big bang for just a few bucks: The impact of math textbooks in California, Evidence Speaks Reports, Vol 2, #5 (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, Economic Studies at Brookings, January 5, 2017); for evidence on teacher feedback and instructional coaching, see Matthew Kraft and David Blazar, “Taking Teacher Coaching to Scale,” Education Next 18, no. 4 (2018); for studies on quality career-technical education, see Shaun M. Dougherty, “The Effect of Career and Technical Education on Human Capital Accumulation: Causal Evidence from Massachusetts,” Education Finance and Policy 13, no. 2 (2018); for research on high-dosage tutoring, see Andre Nickow, Phillip Oreopoulos, and Vincent Quan, “The Impressive Effects of Tutoring on PreK-12 Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Evidence” (working paper 27476, National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2020); and for research on impacts of quality summer school, see Heather L. Schwartz, Catherine A. Augustine, and Jennifer Sloan McCombs, “Commit Now to Get Summer Programming Right,” The RAND Blog, RAND Corporation, April 15, 2021.

[48] ESSA, Section 1003(i): “The state shall include in the report described in section 1111(h)(1) [i.e., state report card] a list of all local educational agencies and schools that received funds under this section [i.e., federal school improvement grants], including the amount of funds each school received and the types of strategies implemented in each school with such funds.”