Suing for peace in education’s culture wars

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a two-part series. Part I urges readers to "listen more, empathize more, and demonize less" in these divisive times.

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a two-part series. Part I urges readers to "listen more, empathize more, and demonize less" in these divisive times.

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a two-part series. Part I urges readers to "listen more, empathize more, and demonize less" in these divisive times.

After the election, I shared my thoughts about how we might achieve a truce in America’s roiling culture wars. In short, I suggested a simple rule: Empathize, don’t demonize.

How might we apply that rule to the culture wars that stalk our corner of the world in education policy?

By culture wars in ed-policy, I mean those disputes that go beyond traditional interest-group politics, such as teachers unions fighting the expansion of non-union charter schools. Instead I’m referring, for example, to the 1619 versus 1776 debate over how to teach the story of our nation’s history, or to controversies about accommodations for transgender students.

Consider the issue of racial disparities in school discipline—a debate in which I have played the role of partisan. There, I now see, I could have done more to lower the temperature and find common ground.

—

For more than five years, I’ve been writing about the discipline issue, ever since the Obama administration released its much-discussed guidance on discipline, which threatened civil rights investigations into any districts with data showing racial disparities in suspensions or expulsions. I have expressed strong concerns about that guidance ever since, which I will get to in a moment, but I always try to preface my arguments with an honest acknowledgment that we absolutely need to take racial discrimination seriously, including in how schools mete out punishment for misbehavior. And I’ve always agreed that the federal Office for Civil Rights has a clear role to play in responding to any complaints of racial bias or discrimination, including those related to discipline.

Still, I understand now that I did not fully empathize with my colleagues who support significant reductions in suspensions and expulsions, especially for kids of color. That’s because I did not completely understand where they were coming from, which I now believe is from a commitment to ending mass incarceration in this country.

I could have done more to try to understand the pain, the real anguish that so many people experience as a result of that system, especially African Americans.

What must it be like to have such a significant portion of your community behind bars, or in fear of the police, or shackled by criminal records?

A few weeks ago, NPR ran a segment on the impact of neighborhood police violence on pregnant women. Yuki Noguchi interviewed a Black woman, Raven Cain, about being pregnant, after multiple miscarriages, just as George Floyd was murdered around the corner from her parents’ home.

CAIN: You know, during that time, it was constant sirens. Then they were saying that the KKK was supposedly in town, and it’s just stressful. It’s like—and then you’re trying to carry a life, and then you’re thinking about them being a Black person in this world and the things that they might encounter.

NOGUCHI: Cain tried to distract herself by hosting a family party to reveal she was having a girl.

CAIN: My dad was just jumping up and down. Like, he was so happy. He said he went in the garage and cried a little bit.

NOGUCHI: Cried partly out of relief—he told her the world wasn’t safe for Black boys.

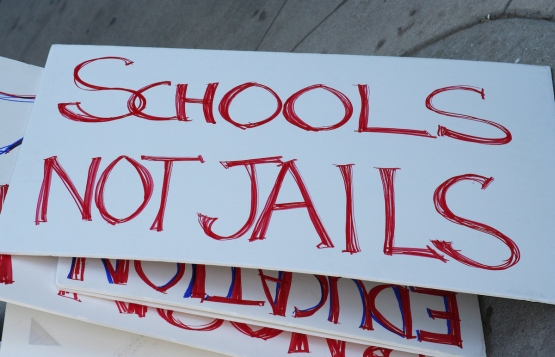

Although improving student outcomes is an important goal for almost everyone in education, for many of our colleagues, reducing the population of Americans behind bars is even more important. And a key step in doing that, they believe, is disrupting the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

I wish I had done more to state clearly that I wholeheartedly agree with this objective, and that we need to do everything we can to keep young people off the pathway to prison. Of course we need to keep our communities safe, but it is a tragedy and a national embarrassment that we have resorted to locking up so many of our fellow citizens, destroying families and livelihoods.

I wish I would have stated unequivocally that, yes, schools absolutely have a role to play in helping to solve this problem.

First and foremost, they can make sure that kids learn to read, given how much we know about the relationship between illiteracy and involvement in the criminal justice system. As students get older, schools must also help them get ready for success in postsecondary education and/or the workplace—to get them on the school-to-upward-mobility pathway.

But most critically, schools, from the earliest age, can help all young people learn how to control their emotions, and their behavior, so as to stay out of trouble and find success cooperating with others. That can be particularly challenging for children growing up in poverty, given the horrific challenges many face at home, from violent neighborhoods to lead poisoning to food insecurity and so much else. And when children do struggle to behave, and they break the rules, or engage in anti-social or even violent behavior, schools should try harder to help them meet behavioral expectations rather than give up on them and “put them out.” In many cases, mental health supports are key.

About all of this I think we can all agree.

But now we get to the hard part. What to do when this all fails? When student misbehavior is dangerous, or chronic, and children aren’t responding to interventions?

Here, I would ask discipline reform advocates to show some empathy for those of us on the other side. We are not happy about suspending or expelling students. But schools that don’t have and enforce clear discipline codes will become unruly and unsafe. That’s not good for students who misbehave, and it is certainly not good for their peers who are studying and trying to learn. Given the nature of our segregated school system, when we are talking about children of color who are misbehaving, we should acknowledge that the preponderance of their peers who suffer the consequences of lost learning time are also children of color.

Many of us discipline-reform skeptics are especially concerned that some of the best- performing high-poverty schools in the country—especially those in high-flying charter networks like KIPP and Achievement First—are facing enormous pressure to ease their behavior standards in ways that may leave them unsafe or disorderly. And that would be a terrible tragedy, given how successful such schools have been in helping their students, almost all of whom are Black or Brown, achieve incredible academic and life success.

To be sure, there are genuine and earnest disagreements between discipline reform proponents and opponents. There are fundamental differences in how these camps would handle the trade-offs between order and safety on the one hand, and the potentially negative impacts of suspensions and expulsions on the other. We also tend to disagree on the best ways to help schools get better at balancing these trade-offs and whether the threat of civil rights investigations is an effective tool for doing so.

But I hope I have demonstrated that it is possible to lower the temperature around a contentious and high-stakes debate by introducing empathy and nuance into the conversation.

If we can reach the point where we acknowledge that this issue, like so many others, is hard and complicated, that that’s a victory unto itself.

It’s now official. Unless Congress pushes back on Secretary DeVos’s request—which seems unlikely—the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests of fourth and eighth grade reading and math that were scheduled for 2021 will be deferred at least a year. That means this vital source of data on student achievement won’t tell us anything between spring ‘19 and autumn ‘22, when we can reasonably expect the next results to appear. This means, in effect, that NAEP is AWOL for the pandemic and its school shutdowns, turning a blind eye to the learning losses that they’re causing.

This also means that state testing in spring 2021 is now more important than ever—and that President Biden’s education secretary should resist all demands for another round of waivers from ESSA’s requirement that all students in grades three through eight should be assessed annually in reading and math. Absent such data, we’ll see both a collapse, perhaps permanently, of results-based school accountability and—more immediately—an appalling dearth of information about who is and isn’t learning what during these challenging times for K–12 education. (Test scores like those released this week from NWEA are welcome, but as that organization itself acknowledges, they aren’t nationally representative, especially given how many students—most of them Black, Brown, and poor—are missing from the data set.)

Bear in mind that states need not request waivers, even when they’re available. They can—and should—continue with their assessment plans, even if the incoming administration flinches when its pals in the teacher unions demand another testing hiatus. Nor do states need to pause their non-ESSA assessments—end-of-course exams and such—even when Uncle Sam wimps out. Bear in mind, too, that state tests are much less complicated to administer than NAEP during times when not all schools are open and not all students are physically present in the schools that are.

NAEP is sample-based, and the accuracy of its ESSA data hinges on whether its tests can be administered to a representative sample of students in every state, as well as the country as a whole. Even for non-ESSA data—i.e., when no state-level results are to be provided—NAEP’s contractors (WESTAT, ETS, etc.) still need a proper sample of students nationwide in the tested grades. That means properly sampling pupils from every demographic group, as well as rural and urban, public and (usually) private, district and charter, etc. This grows difficult, if not impossible, when some schools have kids sitting in them while others don’t, when this pattern varies from state to state and sometimes week to week, and when only some students are physically present in the schools that are open that week. Lacking a valid sample, NAEP data are useless. And while NAEP tests are now taken online, it seems that nobody has yet figured out how to administer it to students who aren’t physically in school on the dates when it’s given. For all these reasons, much as I regret the NCES-NAGB decision to defer NAEP ‘21, I can’t really dispute it.

State assessments, by contrast, don’t depend on sampling. They’re given to every student who is present, and they yield results for those students, results that are reported to parents for their very own daughters and sons. These data are then aggregated at various levels—classroom, school, district, and state—and are sliced and diced in various ways. It’s true that aggregations may be misleading when some kids are tested and others aren’t. But a great deal can be learned about what has and hasn’t been learned about those who are tested. And in many places, the school and district data will be reasonably accurate, at least for some grade levels, and can be compared with 2019 data to generate some of the “growth” data that will prove essential for identifying which schools and districts did particularly well in addressing the Covid-19 challenge and which face the heaviest remediation burdens.

State education leaders should also consider the possibility of slipping their 2021 assessments from spring to fall, by which time we hope that just about every school and student will be back in place. If swiftly scored, that could yield welcome information about learning levels and losses for teachers commencing the 2021–22 school year, and would also provide baseline data against which spring 2022 test results can be compared and achievement growth calculated. For these reasons, if the U.S. Department of Education opts to offer ESSA waivers for 2021, which I hope it won’t, one version of such waivers might require autumn testing in those states that punt in the spring.

Returning to NAEP, let me flag some other portentous and provocative points that Secretary DeVos made in her letter to Congress seeking a delay in the 2021 assessments. In that document, she also outlined and asked for a major overhaul of NAEP operations, stating that the current arrangements are too cumbersome and costly to sustain.

Consider the implications of this excerpt:

It is time for Congress to rethink the entire NAEP program and improve its efficiency, efficacy, and budget. Since 2002, after the No Child Left Behind Act mandated state-level NAEP tests, the program has become increasingly complicated, difficult to administer, and costly. In FY 2002, NAEP’s budget was $42 million, and $23 million was spent on the mandated fourth and eighth grade tests. By FY 2019, NAEP’s budget was $151 million (a more than 250% increase), and the budget for mandated tests was $88 million (a nearly 300% increase). On a per student tested basis, the cost of the core NAEP test has skyrocketed from $67 to $293. Despite the growing costs and complexity, the country still benefits from reliable, periodic national measures of academic progress, but perhaps not at the current pace.

It seems clear that the costs of conducting the core NAEP tests every two years far outweigh the benefits of marginally enhancing well-established achievement trend lines. This is why our FY 2021 budget request proposed exploring the option of administering reading and math assessments on a staggered, four-year schedule. Reading could be paired with writing in a given “literacy” testing year. Two years later, math and science tests could be administered in a “STEM” testing year. This cycle would repeat, providing thematically focused results every two years and covering all subjects in four years.

This would save as much as $20 million per administration—money that could be redeployed for the needed modernization of NAEP or used to expand other important tests, including civics. Other changes that I encourage Congress to explore in concert with IES, NAGB, and the assessment community include moving test administration to the cloud—to eliminate the logistical complexity and cost of sending thousands of test administrators to thousands of schools—and restructuring NAEP assessments on a foundation of technology-enabled adaptive testing, where students’ right and wrong answers drive which questions the student receives, producing more accurate results and, in particular, generating far more accurate information about the lowest performing students who are the primary focus of federal education programs and policies.

Much to chew on here, at least for NAEP mavens such as myself. Moving to a four-year cycle for ESSA testing makes sense to me, at least during non-pandemic times, as does retrieving some of a tight budget for other subjects besides reading and math (and, I would add, some budgetary slack with which to supply regular state-level data for twelfth graders). Moving to a cloud-based adaptive testing system may also make sense but risks forcing a fresh start for every trendline in what’s called “main NAEP.” It may also threaten NAEP’s long-term trend, which now reaches back almost half a century.

NAEP was last authorized in 2002, and it’s surely time for Congress to take a fresh look. But a lot of babies are now splashing around in the NAEP bathwater, and great care must be taken before any of them are discarded—or left soapy and unrinsed.

A long simmering feud between Denver’s school board and superintendent finally burst into the open last week following months of tensions and mutual distrust. Exacerbated by the pandemic and the district’s struggle to balance education and public health, the latest discord follows Denver superintendent Susana Cordova’s recent resignation, a decision widely viewed as not entirely of her own making. The sudden if not altogether unexpected announcement has since rippled throughout the community because of Cordova’s unique standing as a thirty-one-year veteran of the district and her deep ties as a lifelong Denver resident. To many, hers was a “Cinderella story”: Cordova’s mom worked in the district as a secretary and Cordova herself was once a student, became a teacher, and rose through the ranks to eventually become the district’s top boss.

At issue is more than personality: Some members of the board are intent upon moving Denver away from the reform-oriented policies that have characterized the district’s approach for over a decade—policies that once included an acclaimed pay-for-performance system and heartily embraced a “portfolio strategy” that entailed creating new schools and replacing or shuttering distressed ones. This vision for urban public education was once popular nationally, too, but the post-Obama pendulum swing hit Denver hard last year when all of the reform candidates lost their school board races against those who were supported by the teachers union.

To wit, the newly constituted board has been waging a counter-revolution. From deep-sixing the district’s school rating system to discouraging the formation of learning pods, the board’s latest brow-raiser was a nakedly political move to delay the expansion of the district’s highest-rated middle school—run by DSST Public Schools, a local charter school network—a decision that was fortunately rectified by state officials. At the same time, Denver, like other large urban districts, has been embroiled in a racial reckoning that has further charged the political climate. For their part, reform supporters have authored well-intentioned op-eds and issued public statements in Cordova’s defense. These countermeasures have garnered national attention, but they are too little and too late.

Denver was once a shining star in the reform galaxy, but now that star has fallen. How did things go so wrong, so quickly? Many say that Cordova was unfairly saddled with the shortcomings of her predecessor, specifically a failure to adequately engage the broader community. This skepticism gained added momentum when Cordova herself emerged as the sole finalist for the superintendency two years ago. Taken together, they have helped feed a percolating narrative here and elsewhere that testing, charters, and other reform policies are a nefarious plot driven by outside interests. One board member I’ve spoken with in particular often laments neighborhoods in Denver that now lack a school within walking distance.

As both sides continue to trade barbs and point fingers, what’s gotten lost is both the sense of clarity and focus the district once had, as well as a proud albeit imperfect narrative of progress. In the definitive take of Denver’s evolution from 2019, authors Parker Baxter, Todd Ely, and Paul Teske—faculty of the University of Colorado Denver School of Public Affairs—write:

[Ten years ago], it would have seemed wildly improbable that Denver would nearly erase its 25-point lag behind the state in average reading and language-arts proficiency, or that the Latino graduation rate would increase by 17 points, or that more than sixty-five new schools would open. But that’s exactly what happened.

It’s difficult to overstate how much all of this has fallen down a memory hole. In its stead has been an escalating series of broadsides where reform opponents have claimed that the district’s erstwhile decision-makers were racist. Some reformers have responded in kind by asserting that the board’s disagreements with Cordova were in part racially motivated. Never mind that the policies of Cordova and her predecessors were in fact designed to advance racial equity and justice. This blowback has created a poisonous atmosphere with little if any room for compromise, and where policy solutions are often viewed as a function of tearing things down rather than as an opportunity to build.

The city’s mayor and others have laid the blame for today’s predicament squarely upon the doorstep of a “dysfunctional” school board. Former board members are urging current members to seek out board governance training, but the problems facing the district are far larger than poor oversight. No, the bile and vitriol being witnessed in Denver today reflect a collision between fundamentally different worldviews and the pernicious influence of unions.

My background as a state education official pushes me toward seeing what’s happening in Denver through the lens of power politics. I earned my stripes in education reform by being on the front lines of an effort to dramatically remake student outcomes through legislative and regulatory changes that included a state takeover of five low-performing schools. The move was met at the time with equal parts consternation and approval, but the latter won out because of a philosophical alignment among those in positions of authority. Once that alignment crumbled, chaos ensued, and no amount of outside intervention made a lick of difference.

While Cordova was viewed by some as being uniquely positioned to bridge the differences between reform supporters and skeptics, in hindsight it may have been too much of a burden for any one person to shoulder. As Baxter, Ely, and Teske astutely observe:

In our broken education debate, this is the great obstacle to progress: one side wants radical, transformational change and the other wants nearly none. In the space between them, incremental improvement may be the best we can hope for. It may be that [district leaders were] wrong to settle on a middle way, or it may be that no middle path was ultimately sustainable.

Where there’s no middle ground, conflict is seldom resolved through training or mediation, but through the ballot box. Next year, four of the district’s seven school board seats will be up for grabs.

The tumult in Denver suggests that the portfolio strategy may not be politically sustainable. Low academic performance notwithstanding, failing schools still function as mediating institutions that help bind people together. Even the most carefully drawn up of plans to replace or close one can adversely affect an entire community. What might be sustainable is an approach that focuses on curriculum-based reform, but by itself that seems unlikely to yield breakthrough results either.

In the meantime, the one silver lining from Cordova’s departure is that the city may for the first time get a real sense of the district’s new direction. Now unfettered, a changing of the guard in the superintendent’s chair should also lead to a realignment of the district’s central office. Although it’s hard to imagine the academic needs of Denver’s students getting much shrift in this new regime, uncertainty is likely to linger through next fall, which is when the board is hoping to have a new leader in place. No matter who that person is, however, it could be years before the political rancor subsides enough to allow for any real rapprochement.

Two groups likely to be disproportionately affected by Covid-19-related learning disruptions are students with disabilities and English language learners. A pair of new research briefs from the American Institutes for Research, part of a larger series of releases, provide insight about charter and district schools’ efforts to provide quality services to these at risk student groups. From May 20 through September 1, leaders from a nationally-representative group of school districts and charter management organizations responded to a survey that covered school closures, distance learning approaches and challenges, grading and graduation, staffing and human resources, and health, well-being, and safety.

The brief spotlighting English language learners (ELs) includes data from over 750 survey respondents from across the country.[1] Researchers were interested in two specific areas of support for ELs: The types of resources provided to students and families and the instructional expectations of teachers.

The good news is that a majority of respondents reported providing EL-specific distance learning resources, learning materials in Spanish (no other language provision was queried), and interpreters or liaisons for EL families. The less-good news is that district typology mattered greatly in these responses. Rural districts were far less likely to provide these supports than were their urban counterparts, and districts with lower percentages of ELs were also less likely to provide them than districts with high percentages of ELs. While this may seem like a logical outcome—more ELs means more supports for ELs—it could also mean tens of thousands of English language learners all over the United States were receiving little or no targeted educational support at this most critical time. It also seems to bolster what other evidence indicates: The robustness of a school’s educational program prior to the pandemic is a good indicator of how well it pivoted to a distance learning model.

The spotlight on students with disabilities (SWDs) illustrates almost across-the-board struggles for respondents. Closed-response survey items ask about schools’ ability to properly comply with various aspects of the federal IDEA law during a pandemic and to provide “typical” support services to SWDs and their families—think accommodations for completing in-class work, one-on-one supports, and the like.

Their reported difficulties are consistent with other research and anecdotal evidence from spring 2020. AIR survey responses indicated that nearly three-quarters found it more difficult to provide appropriate instructional accommodations for SWDs during school closures, while 82 percent said that providing hands-on instructional accommodations and services was more difficult. Even providing speech therapy proved more difficult for the majority of districts in a distance learning model. Rural districts reported more struggles than did their urban counterparts, but somewhat surprisingly, high-poverty districts often reported fewer struggles than did low-poverty districts. For example, nearly 55 percent of low-poverty districts reported they had more difficulty complying with certain aspects of the federal IDEA law, while just 47 percent of high-poverty districts reported the same. No conclusions are reached on why this might be, with discussion focusing more on the areas where high-poverty districts reported struggles.

There was one open-ended survey item which provides some encouraging news for the 2020–21 school year. The question asked “Has your district used any other strategies not mentioned in previous questions to support SWDs in a distance learning environment?” Innovations described by respondents included implementation of live telehealth therapy sessions, efforts to replicate the classroom environment in students’ homes, and an increased commitment of time and personnel for one-on-one virtual interaction with school staff and SWDs. Hopefully, these innovations have been replicated, boosted, and sustained.

SOURCES: Patricia Garcia-Arena and Stephanie D’Souza, “Spotlight on English Learners,” and Dia Jackson and Jill Bowdon, “Spotlight on Students With Disabilities,” American Institutes for Research (October 2020).

[1] The AIR briefs, including these two, all use the term “district” universally when speaking of survey respondents; it is assumed here that the term includes charter schools and charter management organizations, but the veracity of that assumption is unclear from these briefs or the survey’s technical supplement. CMOs were surveyed, but their responses are not, it appears, separated from those of traditional districts.

Triennially, we Americans await the results of the international PISA tests with equal parts hope and dread, although who knows yet if we’ll get a bye for 2021. While we hope that this will finally be the year that our students have somehow whipped fill-in-the-blank country at last, we are also likely preparing ourselves to try and figure out, once again, why we can’t ever beat Finland. Is it the students, the education system of that country, or some combination of the two creating hard-to-beat, stellar outcomes?

The strong influence of parents on student achievement has been widely documented going back to Coleman in the mid-1960s. A number of research studies, plus Amy Chua’s widely-noted book, have added to the literature in recent years. A new report from two European economists tries to isolate the influence of tiger (and chestnut bear) moms on what they term human capital achievements, using PISA scores as evidence.

The researchers look at the achievement, via tests administered between 2003 and 2015, of more than 53,000 students who are second-generation immigrants from thirty-one PISA countries.[1] The idea is that, if some portion of the influence of the origin country’s education mojo was transferred via the parents, the scores of these immigrant students should more closely resemble those of the origin country—even if the kids no longer attend school there—than they resemble those of the new host country.

The main results bear out this hypothesis in a relationship described as “positive and tight.” That is, the score gaps that appear between native students in two different countries are largely preserved across the scores of second-generation immigrants. For instance, a Finnish immigrant student living and learning in another country will outperform, say, an American student by about the same amount as a native Finn still living and learning in Finland does, regardless of which country the immigrant student now calls home. These replicated test score patterns point to strong influences of home, with parents as the most likely conduit for transferring the influence.[2] To dig deeper, the analysts run a regression using individual math scores for those second-generation immigrants as the dependent variable and controlling for fixed effects of the school attended in the host country, for students’ demographic characteristics, language spoken at home, and family socioeconomic status. While the correlational pattern of cross-country test performance weakens upon regression, it is still positive and highly significant.

Attempts to pin down the exact mechanisms whereby parental influence is transmitted are not entirely successful. Observable socioeconomic characteristics of parents—such as education level and income—while easily isolated for analytic purposes, account for just 15 percent of the cross-country variation in test performance. It’s not clear what else is going on at home. Interestingly, the magnitude of the inferred unobservable characteristics, such as parenting style and cultural values, actually appears to be greater for parents who acquired very little education in their home country—and were therefore less exposed to the education system—implying influences that are far removed from formal education and seemingly more ineffable and innate.

But what to with these findings? Education reformers often look at school systems, buildings, and classrooms as the places to intervene to boost educational outcomes. While improving such inputs as teaching quality and curriculum is vital and valuable, research suggests these are likely not enough by themselves to improve human capital to the desired level. Parental influence is the key. The good news is that cultural values that prioritize education, perseverance, learning from failure, and the benefits of hard work are free and require no infrastructure to transmit and reinforce. The bad news is that it’s hard to come up with interventions in schools or the greater society that might promote such values where they are in short supply. Perhaps the best option is for schools to work to build new success mindsets and to boost such mindsets where they already exist. This new report seems to support this need.

SOURCE: Marta De Philippis and Frederico Rossi, “Parents, Schools and Human Capital Differences across Countries”, Journal of the European Economic Association (November, 2020).

[1] While the PISA data include a much larger overall sample of countries from which parents have emigrated, the researchers limit their analysis to origin countries with no fewer than one hundred emigrant parents represented so as to strengthen the comparison sample.

[2] It is not stated in the paper, which is focused on those immigrant students who achieve higher than native students in their host countries, but the implication is that effect works in reverse also.

On this week’s podcast, Mike Petrilli and David Griffith are joined by Checker Finn, who discusses Senator Lamar Alexander’s K–12 education legacy. On the Research Minute, Adam Tyner examines research on why efforts to boost student motivation may be misguided.

Christopher Cotton, Brent R. Hickman, John A. List, Joseph Price & Sutanuka Roy, “Productivity Versus Motivation in Adolescent Human Capital Production: Evidence from a Structurally-Motivated Field Experiment,” NBER Working Paper #27995 (October 2020).

If you listen on Apple Podcasts, please leave us a rating and review - we'd love to hear what you think! The Education Gadfly Show is available on all major podcast platforms.