Why are charter schools more popular in some states than others?

By Michael J. Petrilli

By Michael J. Petrilli

The August release of the latest Education Next poll set the education-reform field ablaze, for it showed a sizable and worrying decline in support for charter schools. We wonks weighed in with our best guesses about what might explain this unexpected trend. Among the factors raised: the overall political environment as we passed from the Obama Era to the Age of Trump, which might chill support for charters on the left; charter scandals and lackluster performance, at least in some states; and the movement’s own obsession with ultra-progressive causes, which might impede support on the right. If only we could improve charter quality, some advocates claimed, we’d see our poll numbers turn around. Or perhaps, others wondered, we need to widen the base of charter support by expanding charters into the affluent suburbs.

Plausible speculations all, but speculations nonetheless.

Now, however, we have a bit more data to inform our analyses. A major education policy organization—a credible source that has asked to remain confidential—gave me access to survey results from a 1,000 person national poll with 300-person “supplements” in a dozen states. The data come from summer 2017, and it happens that the pollsters included a question about charters—not a great question but one that allows us to test out some of the hypotheses about waning charter support.

The question put to a representative sample of registered voters was: “Please indicate whether you support or oppose creating more charter schools—public schools run by private companies or nonprofit organizations—to compete with traditional public schools.” You don’t have to be a charter school apologist or polling expert to see that this question is worded in a very charter-unfriendly way. “Private companies” feeds into the narrative that charters are about “privatization”—a concept that many voters hate—and very few charters are actually run by such firms. Many voters also don’t like the notion of public schools “competing” with one another.

But it doesn’t seem to matter because the survey found that 40 percent of Americans support charters, virtually identical to the 39 percent identified by Education Next with a question worded much more fairly. Still, keep the language in mind.

Now let’s look at how charters fared in the state-by-state polls (nine of the twelve states have sizable charter sectors). Here are the results, in order of charter support. Keep in mind the small sample size, which makes minor differences less reliable.

Figure 1: Support for charter schools in nine states

Now we have another Rorschach test for reformers. What to make of this? Thanks to data dug up by our crack research intern Nicholas Munyan-Penney, I was able to investigate lots of possible explanations. Of course, with only nine data points, all of this must be taken with a measure of skepticism. But let’s look for some patterns nonetheless.

At first glance, it looks like simple ideology could be at play. The top two states for charter support are red; the notion of competition probably plays well there. And deep-blue Illinois lands near the bottom.

But it’s not so simple. There’s California, bluest of them all, in third place. And what is Louisiana doing so far down?

Could voters be responding to school quality? (Please let that be the answer, I hear all of you good-government types screaming!) No doubt Ohio has been (in)famous for its lackluster quality and its numerous scandals, so the last-place spot is well deserved. (Let me point out that we at Fordham, along with many partners, are making some real progress at fixing that.) But according to CREDO’s analysis of year-to-year math gains, New York’s charters are the best, followed closely by Tennessee, Louisiana, and, further back, Illinois. Charters in California, Colorado, and Georgia all do about the same as traditional public schools, while Arizona and Ohio charters do worse. Put all of this together and it’s a big jumble.

Figure 2: Support for charters schools versus their impact on math achievement

Could it be the size of the charter market? Are charters more popular when there are more of them, or when their students make up a greater percentage of the school population? No, that would put Arizona, Colorado, and Louisiana at the top of the list, and Tennessee at the bottom. Maybe charter schools are more popular in growing states, where they can serve as a “release valve” for growing public school populations. That could explain Georgia and Tennessee, but what about Colorado? I also don’t see a relationship between charter school growth and their popularity, or lack thereof.

So what is it?

Here’s one last thought, inspired by the writing of Matt Ladner and Derrell Bradford: Perhaps charter schools are more popular when they serve more affluent students, not just low-income kids. Let’s take a look.

Table 1: State charter school support based on the percentage-point difference in the proportion of students eligible for free or reduced price lunch in charter and traditional public schools

|

State |

Support for Charters |

Difference in FRPL Rate (Charters - TPS) |

|

Georgia |

50% |

+6% |

|

Tennessee |

45% |

-26% |

|

California |

42% |

+3% |

|

Arizona |

40% |

+12% |

|

Colorado |

39% |

-15% |

|

New York |

38% |

-28% |

|

Louisiana |

37% |

-8% |

|

Illinois |

33% |

-38% |

|

Ohio |

24% |

-30% |

What this shows is that, for example, Georgia’s traditional public schools serve a higher proportion of low-income students than Georgia’s charter schools do—a difference of 6 percentage points. In Ohio, meanwhile, traditional public schools on average have 30 percentage points fewer students eligible for free or reduced price lunch than do charter school peers.

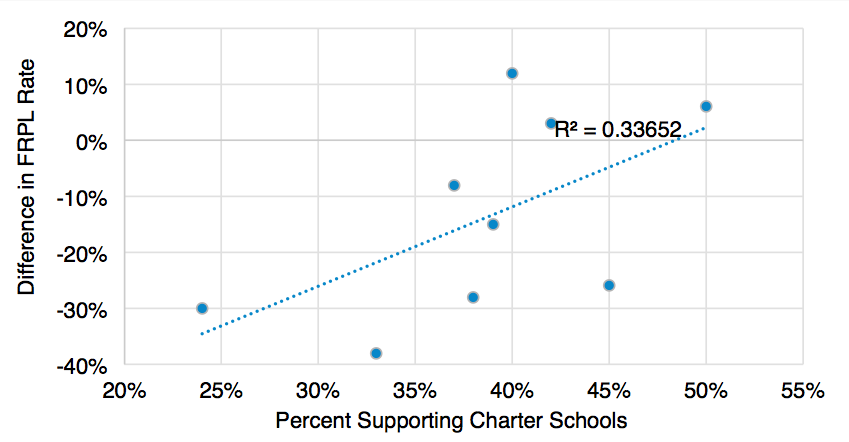

And, sure enough, there appears to be a relationship, with a few outliers. Let’s see that visually.

Figure 3: State charter school support versus the percentage-point difference in the proportion of students eligible for free or reduced price lunch in charter and traditional public schools

Boom! To be clear, I’m not going to present this to a peer-reviewed journal; this is hardly rock-solid evidence. But it sure suggests to me that, if we’re looking for a generalizable explanation for state-by-state differences in support for charters, the degree to which they serve middle class kids and not just low-income children might be a leading candidate.

Yes, there are exceptions. Support for charter schools in Tennessee should be much lower according to this theory; perhaps they are helped by the state’s conservative leanings and the schools’ strong track record on quality. I also can’t explain why charters aren’t more popular in Arizona or Louisiana. But this certainly shows the strong headwinds faced by the sectors in New York, Ohio, and Illinois.

For many states, then, charter demography may well be destiny, at least when it comes to public support, at least in this moment in time.

If that’s true, what does it mean? First, it would put charter schools in line with the old liberal adage that “a program for the poor is a poor program.” It’s hard to maintain public support for a targeted investment, especially when the beneficiaries are themselves poor and relatively powerless. This is why Social Security is much more popular than most welfare programs.

Second, it might tell us about how the public views schools. Voters might perceive “schools for poor kids” as low-quality schools. That is of course unfair and prejudiced, but it may reflect the reality of public opinion. And not just in education. We perceive neighborhoods that affluent people can afford as “nice neighborhoods”; restaurants that affluent people can afford as “nice restaurants”; and public schools that affluent people can afford as “nice schools.”

Third, and less cynically, perhaps when charter schools serve a broader population, including middle class kids in the suburbs, more people come into contact with them. And familiarity breeds positivity.

Regardless, these data provide yet more reason for the charter movement to get busy building schools in neighborhoods far and wide, and working to serve affluent kids, low-income kids, and everyone in between. Charter schools for poor children have done wonders. But if we want to maintain support for them, they ought not be the only type around.

How can schools encourage responsible and engaged citizenship? This question has moved from ever-relevant to deeply urgent by a political climate defined by coarsened discourse, sharp polarization, and profound distrust.

While many educators are justifiably demoralized by our current situation, some choose to be hopeful. Richard Kahlenberg and Clifford Janey spoke for many in education when they asked in The Atlantic if 2016's crazed election cycle might represent a "Sputnik moment" for civic education: Just as the Soviet Union's launch of the first artificial satellite in 1957 drove an urgent and renewed national commitment to science and math education, perhaps concern about our contentious political discourse and decayed common knowledge base will do the same for civic education today. Forty years ago, all eyes were on the stars, and educators leveraged the public attention to improve science and math education. Today, all eyes are on Washington, and by extension on our schools: Could civic education undergo a similar transformation?

A promising sign comes from Louise Dubé, executive director of iCivics, an educational content provider. In a recent phone conversation, she told us that the explosion of interest in her organization's civic education tools and online games during the election year has largely continued into 2017. "User growth was off the charts during the presidential campaigns, and even now, significantly more users are consistently engaging at higher rates than before," she said.

That's good news, and we could use more of it. Less than one-quarter of eighth graders scored "proficient" or higher on the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress civics exam—a rate that makes the most recent NAEP reading scores (34 percent at or above proficient) look comparatively robust. Indeed, it's fair to say that the citizen-making role of schools has become a forgotten purpose of public education. In 2016, the Education Commission of the States found that, while every state requires social studies or civics content in their curriculum, only seventeen include it in their accountability frameworks. Math, by contrast, is included in all fifty states. Likewise, a 2015 review by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, the education-policy think tank where Robert is a senior fellow, showed that the overwhelming majority of "mission statements" of the one hundred largest school districts in the United States made no mention whatsoever of civics or citizenship, or of schools' role in preparing students to participate in our democracy.

The practitioner's problem

While the need to double down on civics in schools has become painfully obvious, it is less obvious how we should do so. Many high schools are responding by infusing authentic civic experiences into the school day—bringing students to state capitals, helping them organize "get out the vote" drives, creating "social change" projects, and regularly teaching current events. As former co-teachers of a class designed to pair government theory with current events, we support such practices. But we are also well aware of the substance-thinning traps that well-meaning civics teachers can fall into when they focus on projects geared mainly toward engagement or relevance.

But before sharing our thoughts on how best to blend traditional content with "hands-on learning," let's start by looking at how both traditional in-class and operational civic instruction fall short on their own. Consider two scenarios.

Citizens of the state of boredom

A classroom of seventeen-year-olds collectively half-listen to a teacher delivering a lecture on the United States' system of divided government. They are in their junior or senior years of high school, learning about the basic makeup of the system that structures their lives, a system that they will soon be able to influence—one that is defined by conflict and intrigue, but that is widely regarded as one of the most brilliant and successful experiments in the history of the world. And they're bored.

But the teacher isn't. She intones, "And as Madison said in Federalist No. 51, 'Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.' His thinking was that, since humans are naturally rapacious, vindictive, and selfishly ambitious, the best governments are those that pit the ambitions of individuals against one another, with the idea that competition produces a common good. So, given what we've read of the Federalist Papers so far, and what we've discussed in class, how did Madison's assessment of human nature lead to his belief in the need for a government with a strong system of checks and balances?"

Silence.

What's missing? What could this teacher have done differently?

Sugar-rush civics

Here's a different, increasingly common scenario: This time it's a couple of buses of fourteen-year-olds pulling up to the state house in Tallahassee, Florida. The students march through the halls, as their social studies teachers narrate what they're seeing, and remind them of the legislative issue they have prepared to discuss with the state senators who have cleared time on their calendars to meet and pose for photographs.

Their conversations mostly go well. The state senators love the photo op and the chance to field softball questions from the kids about the bill for which students are lobbying. Teachers beam at the students, satisfied with themselves and pleased that their charges came across as well-prepared. Then the buses are loaded back up and everyone leaves, probably with a fairly strong understanding of their chosen issue and with the powerful lesson that where they live, individuals—even young ones—have a say in state issues.

Potent stuff, certainly. The kids came to appreciate the core advantage of democracy: It endows every individual with political power, a power best exercised by the knowledgeable. Students had read up on their issue, sought out their representatives, and lobbied for their cause: That's what citizenship in a democracy looks like.

But while this type of field trip and other methods for teaching "operational citizenship" are essential, they're not sufficient. If not closely paired with core information on the structures and theories of government, these methods are akin to a science teacher's doing a lab on building model volcanoes without teaching students the geophysical causes of volcanic eruptions. It's science, it's cool, but it doesn't support in-depth understanding—and it would be a lot stickier if it did.

Although students would probably learn something from building a model volcano, think of how much more they would learn if they did so after completing a few lessons on tectonic plates. Each action would take on extra layers of meaning, as the students connected what they're doing now back to what they learned before. A science class made up exclusively of labs would almost certainly be better than nothing, but infusing those labs with relevant knowledge makes for a far richer and more engaging experience.

Likewise, authentic civics activities unsupported by knowledge of government structures and basic political theory risk providing something of a civic education sugar rush. The momentary thrill of public engagement doesn't provide enduring knowledge—the how it's done and why it matters—of deep civic education. Conversely, a close study of foundational documents and historical movements risks seeming irrelevant unless students can see their effects on the world today.

Why operational citizenship needs political theory

In short, our zeal to make civics "relevant" could end with us forgetting to teach it—accidentally swapping out essential information for "hands-on experiences." On the basis of evidence like those aforementioned NAEP results, as well as our own observations, we fear this split is increasingly happening in schools. This is especially discouraging because studies of government, economics, and history give kids (and adults) the conceptual frameworks they need to interpret their civic experiences—from reading breaking news to engaging in exchanges with politicians to understanding the voting behavior of their families—with sophistication and nuance. Operational citizenship needs political theory; otherwise we end up with a civic-education snake with its head cut off—a whole lot of action that lacks intentionality, context, and, ultimately, meaning.

Rather than thinking about traditional government and civics instruction as something separate or exclusive from field trips to state capitals or mini-lessons on current events, educators would do well to remember the power of each to enliven the other. So, rather than closing the textbook on Marbury v. Madison before the current events discussion, have your students keep it open. Ask them how that decision might help us make sense of confirmation-hearing debates between Supreme Court nominees and U.S. senators on the role of the court in making and interpreting law.

Rather than scheduling that field trip to the Tallahassee state house during the unit on a particular local issue, schedule it during the unit on federalism. Make kids explore why there are so many different types of lawmakers in our country, charged with so many different tasks, often fighting over jurisdiction on so many different issues. Why make it so complicated, rather than just concentrating power in the hands of a few people—wouldn't things run more smoothly that way? Suddenly, students aren't just walking down ornate halls to discuss a single bill, they are witnessing the material consequences of the founding fathers' fear of monarchy.

Case study: The hybrid model

Both of us have worked with Democracy Prep Public Schools, a charter network based in Harlem that has a mission of educating "responsible citizen scholars." At the high school level, as part of that mission, all seniors are required to take a course titled Sociology of Change—which happens to be a helpful example of the kind of hybrid civic education approach we've been advocating.

In this capstone class, each student is tasked with developing a Change The World project, which diagnoses and addresses a social problem that irks them—whether local, national, or global. Over the years, students have launched book drives for underfunded schools abroad, Black Lives Matter-inspired protests outside local police stations, mentorship programs that pair Democracy Prep high school students with middle school students, and literally hundreds more—all of them driven and implemented entirely by students. The project is a good example of what we've been calling authentic civics. But here's the catch: Class time is generally divided between hands-on work on their projects and whole-class considerations of The Prince, Rules For Radicals, the Federalist Papers, and other seminal writings on government and citizenship.

The class aims to acquaint students with timeless theories that teach how to accumulate and use political power at the very moment that they are expected to utilize those theories in service of issues that are important to them. Students end the year with the experience of having used political theory to advance personal projects, and with a basic understanding of how to navigate governing structures to realize specific goals.

In addition, every Friday the Sociology of Change course is supplemented by a Senior Seminar in American Democracy, another class common to all Democracy Prep seniors, and one that the two of us had the pleasure of co-teaching at Democracy Prep Charter High School in New York City during the 2015–2016 school year. This seminar endeavors to teach foundational questions in American government via explorations of current events. For example, when Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died in early 2016 and the internet exploded with cries of grief and joy, our students used the opportunity to consider Scalia's ideas about the role of the courts in American government, and to compare the late Justice's "originalist" vision of jurisprudence with that of other legal experts who favor a "living Constitution" approach.

As many educated adults argued about whether it was right to take pleasure in a person's death, we went on to talk about whether an unelected panel of nine Yale and Harvard graduates should be able to check the elected branches of government. Why, we asked, would the founding fathers create an institution so powerful and seemingly anti-democratic as the Supreme Court? Did they think there were limits to popular rule? Were they right? Could that concern help explain the seemingly nonsensical existence of the Electoral College? Students ended the term writing a paper that responded to these questions: "Should a free society prioritize popular rule or reasonable rule? Must these priorities always be in tension? Why or why not? Use evidence from our texts and current events to support your argument."

Connections between theory and current events don't always come easily, and we sometimes failed to bridge the gap. In the midst of a lesson on the so-called elastic clause, a student in our class asked, "What do these theories have to do with me? Why aren't we learning about what politicians are doing right now? I mean, that stuff matters." The comment was devastating to us as civics educators. The elastic clause (Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution) gives Congress the right to pass any laws "necessary and proper" to fulfill its enumerated duties—amounting to a huge expansion of power. The student's question was an indictment of the disconnected approach we had veered into without realizing it: We were teaching them about a Constitutional provision constantly employed by Congress to pass laws that encircled the student questioner's life, but we may as well have been yapping about Marcel Proust's gastrointestinal travails.

At the start of the next class, we looked at recent situations in which the elastic clause had been put to use, then together considered how our society might be different if it didn't exist. Social studies teachers are always teaching current events, whether we realize it or not. The more we realize it, the better we become at our jobs. History, government, and civics textbooks can be flashlights that illuminate the machinations of our society and help our students define their roles in shaping it. But if we forget to orient our textbooks toward the world, the lights they produce are wasted.

Experiences, contextualized

Experiential learning is most powerful when it draws upon prior knowledge. If what you learned in a classroom can be used to make sense of what's in front of your nose, chances are that information will stick—and survive to add another layer of meaning to future experiences. So, teachers and school leaders: Please, go ahead and build in time for students to engage in authentic civic experiences. They need them. But remember that they also need to know what they're doing and why it matters within our system of government. Without basic background knowledge, those experiences just won't mean much.

Andrew Tripodo is a social studies and debate teacher at the Cushman School in Miami and the head of curriculum design at Knowledge of Careers, Inc. He was previously the history curriculum specialist at Democracy Prep Public Schools.

Editor’s notes: A version of this article was first published in the ASCD’s Educational Leadership journal. It is not available for reprint without the permission of ASCD.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

A series of articles in Slate has upped the ante on the mounting evidence that online credit recovery has a rigor problem, even as such programs have become nearly ubiquitous across the country. As the reporter wrote, the practice of offering online credit recovery seems to be “falsely boosting graduation rates” at the expense of rigorous learning experiences for students.

What’s sad, and often unmentioned, is that we shouldn’t be surprised. People are rationally following their incentives—to boost graduation rates and make sure students have a high school diploma in hand. Because few states tie external, objective assessments for required high school courses to graduation, there is accordingly little attention paid to the underlying quality of online credit recovery courses.

This means, though, that this is a system-wide problem that goes well beyond credit recovery courses. Credit recovery is just where the incentives are most urgent to make sure students get credits as quickly and cheaply as possible—regardless of what they have learned.

Our system’s lack of attention to individual student outcomes, and a preoccupation with input-based measures, such as the amount of time students spend learning and easily manipulated metrics such as graduation rates, have led to the current situation.

Although we might not be getting what we want, we are certainly getting what we deserve.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

On this week's podcast, Mike Petrilli, Alyssa Schwenk, and Brandon Wright discuss why charters enjoy more support in some states than in others. During the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines the impact of administrator and parent support on teacher retention.

Steven Bednar and Dora Gicheva, “Workplace Support and Diversity in the Market for Public School Teachers,” Education Finance and Policy (August 2017).

A study conducted by two University of Virginia professors examines the effects of universal preschool in Florida on grade retention in the early elementary grades. Expanding state-supported preschool programs has been a big push nationally. In fact, the percentage of four-year-olds participating in such programs has more than doubled from 14 to 32 percent between 2002 and 2016.

In 2005, Florida introduced the Voluntary Pre-Kindergarten Program (VPK), a free universal preschool initiative, and as of 2015 the program serves more than three quarters of four-year-olds in the state. Overall, the program has been criticized for low funding levels and not meeting key indicators for quality (as deemed by the National Institute for Early Education Research)—but until now there’s been little to no empirical research examining the program’s impact.

Analysts study whether VPK led to drops in the likelihood that children would be retained between kindergarten and third grade. They track eight cohorts of students, totaling 1.5 million, who enrolled in kindergarten for the first time between fall 2002 and fall 2009. The first four cohorts did not have access to VPK when they were four-year olds; the later four cohorts did. The cohorts are followed through their enrollment in third grade or through the 2011–12 school year, whichever occurs first. Since the program is voluntary, analysts employ a number of rigorous techniques to account for selection and various unobserved characteristics that could impact the comparability of the two groups.

The key finding is that VPK participation significantly reduces the likelihood that children will be held back in kindergarten, but this effect disappears or “fades out” by second grade. In other words, by the time students complete the second grade, there is no difference in the probability of having been retained at least once between VPK participants and non-participants. In short, the initial drop in retention rates is counteracted by increases in subsequent school years. That’s because, conditional on not having been previously retained, VPK participants were actually more likely to be retained in second grade compared to similar non-participants. Analysts hypothesize that, “participating in VPK helped children transition into kindergarten and the expectations of a formal classroom setting more smoothly” [but] “[i]t may be that the program was less effective preparing children for the academic demands of schools that are more relevant in second grade retention decisions.” Perhaps.

Add this to the growing number of studies that find “fade out” of preschool effects, including the big Head Start evaluation, as well as this study of Florida’s third grade retention policy. That’s not to say that preschool programs and interventions such as these don’t have benefits, such as improved non-cognitive skills, considering the respective evaluations of each are typically measuring a narrow set of outcomes. But it should serve as a call for researchers to design studies that can begin to explain why impacts on our youngest learners appear so short-lived.

SOURCE: Luke C. Miller and Daphna Bassok, “The Effects of Universal Preschool on Grade Retention,” Education Finance and Policy (September 2017).

Those who know Fordham know that we have a long history of reviewing state standards. In fact, our very first publication twenty years ago was a review of state English standards conducted by Sandra Stotsky. But when the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) were developed and adopted by forty-five states in 2010, we imagined our days of reviewing fifty different sets of state standards were over. Seven years later, however, many states have made changes to the CCSS—or dropped them entirely. But are these changes an improvement or step back from the Common Core? And how different are these revised standards from the CCSS, really?

In a report released earlier this month, Achieve takes an initial look at English language arts (ELA) and mathematics standards in twenty-four states that originally adopted the Common Core but have since made revisions, large and small. The report’s findings for ELA standards are overwhelmingly positive. They “almost universally reflect the key elements research has identified as necessary foundations for college and career readiness.” ELA reviewers evaluated standards against seven high level indicators including how well they address foundational reading and writing skills, grammar and convention skills, and reading standards for literary and informational texts. While strong overall, one significant and troubling area for improvement cited is that several states still lack clear, explicit guidelines for evaluating text complexity, which is determined by a vocabulary, sentence length, organization and structure, and any background knowledge required for a reader to understand it.

Math standards were similarly assessed against several high-level “readiness” indicators, such as the extent to which they focus on arithmetic in K–5, emphasize the importance of mathematical practices, and are sequenced appropriately across grades. But the findings were slightly less rosy: Although most standards were found to be generally high quality, the report concludes “a few states fall short.” The most frequent deficiencies cited are that statistics and modeling are not given special emphasis in states’ high school standards, and that certain states don’t require elementary school students to know single-digit sums and products from memory.

As states continue to revise and replace the Common Core, it is becoming increasingly important to understand the nature and caliber of those changes. Achieve’s report is a helpful initial step to ensuring all states are setting their students up for success at college or in their careers.

Fordham is also currently conducting our next round of state standards reviews, which will be released in early summer 2018. Our report focuses on CCSS states that have made substantive changes or those that never adopted Common Core in the first place. In contrast to Achieve’s aggregated-state study, it will include detailed reviews of individual state's ELA and math standards, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses and offering a set of custom recommendations for their improvement. In other words, our days of reviewing standards aren't over yet!

SOURCE: “Strong Standards: A Review of Changes to State Standards Since the Common Core,” Achieve (November 2017).