All students should have the option of daily in-person instruction

With Covid-19 cases dropping, teachers getting vaccinated, and new data and guidance coming in all the time showing th

With Covid-19 cases dropping, teachers getting vaccinated, and new data and guidance coming in all the time showing th

With Covid-19 cases dropping, teachers getting vaccinated, and new data and guidance coming in all the time showing that schools can operate safely with mitigation strategies in place, more Ohio schools are shifting to in-person schooling. For some families, that means a long-awaited return to a five-day-a-week in-person schedule. Their children will once again benefit from face-to-face learning and daily interactions with teachers and peers. Given the serious concerns about students’ academic and social-emotional well-being, this couldn’t come a minute too soon.

Sadly, other Ohio families won’t be as fortunate. Their schools will be open for in-person instruction a couple days a week, but remote learning will drag on in the form of “hybrid” models, a structure that is hard on both teachers and learners. As of the end of February, the Ohio Department of Education reported that one in three Buckeye districts were still using only remote or hybrid models without the option of full in-person education for any pupils.

The holdouts include some of Ohio’s largest school systems. In Columbus, for instance, elementary students recently began hybrid learning, but the district has no plans for returning to daily in-person instruction. Most Columbus high school students will remain in full remote mode until late March when they will finally transition to a hybrid schedule. But, again, no full-time option if you’re a district high school student, even as a number of private and public high schools have been fully open since last fall.

Cleveland recently unveiled its much-anticipated plan to begin in-person instruction, but that plan also centers on hybrids. For parents there, as in Columbus, the well-documented frustrations and learning losses associated with remote learning and “half-school,” as one parent recently put it, are sure to continue.

For now, the state is allowing this. For priority status in the state’s vaccination program, Governor DeWine asked schools to offer at least hybrid learning. That was a successful nudge for school systems to move away from fully-remote offerings and get some students back into classrooms at least part time. But it doesn’t help families who are sick of remote learning and want their children back in school full time.

What to do? One option, albeit blunt, is for lawmakers to wield their authority and require all schools to offer full in-person instruction to any family that wants it. This route—currently being discussed in Massachusetts—would be controversial, of course, likely provoking an outcry from district administrators and teachers unions. Another option is for parents to pressure their local school boards to reopen five days a week, something that’s happened in parts of Ohio and other places in the country.

Yet another possibility is to give families access to private schools that are open five days a week. As national surveys indicate, private schools are more likely to have continued to operate in person over the past year. That’s true here, too, as we see in a recent article from Southwest Ohio. In their enrollment efforts for next fall, those private schools have even promoted their ability to stay open and offer in-person instruction. The problem, of course, is that only families with the disposable income to afford tuition—or those who are eligible for the state’s private-school scholarships—have access to these schools. Under current law, EdChoice offers scholarships for students attending low-performing public schools or from low-income households.

A straightforward adjustment to Ohio’s EdChoice program could open private-school opportunities to parents who aren’t satisfied with the hybrid learning available at their district schools. State lawmakers need only expand scholarship eligibility to include any child attending a public school that is not offering in-person instruction five days a week. This is something that legislators in Georgia, Maryland, and New York have proposed. Students would immediately become eligible for an EdChoice scholarship if their public school offers only hybrid or remote learning opportunities. If legislation passes quickly, this could enable students to transfer to private schools later this spring. But given the time needed to enact bills, it would more likely apply to children whose schools announce they’ll start the year in remote or hybrid mode or switch to such learning models for an extended period during the year (absent a public health emergency declared by the governor).

Some will say that there’s no need to change the scholarship law because schools will surely be open in person, full time by autumn. If that turns out to be the case, terrific. We all want to see schools open and operating normally next year. But we can’t count on it. Some U.S. school systems are already planning for remote learning in fall 2021. Labor challenges could also impede progress in fully reopening schools. Returning to Cleveland, for instance, the local union immediately blasted the district’s reopening plan. “CTU members will return to in-person learning when it is safe for us and our students to return. Until then, we will continue educating Cleveland’s children remotely,” said its president.

Parents and students who want to be in a classroom shouldn’t have wait on the sidelines if their local district isn’t offering daily in-person instruction. That’s not to say parents should be rushed. Remote options should be offered until all families are comfortable sending their children to school. Some may have legitimate reasons to prefer the online version. But polls indicate that a sizeable number of parents (about one in three) want daily in-person instruction for their kids. That demand will only rise if cases continue to decline and schools prove that it’s possible to operate safely. The best way to ensure that all families have in-person opportunities—should they want them—is to empower parents with a full menu of public and private school options.

Last week, the Ohio House unveiled House Bill 110, the legislative vehicle for Governor DeWine’s budget proposal. The bill contains plenty of smart education provisions, including $1.1 billion in additional Student Wellness and Success funding, an increase in supplemental funding for high quality charter schools, and initiatives aimed at improving the technical skills of Ohio high schoolers and adults.

But tucked deep into the bill are troublesome changes to graduation requirements. At first glance, they seem small. But if they’re included in the final version of the budget, they’ll devalue an Ohio diploma and undermine years of work by a wide variety of stakeholders to create fair and robust graduation requirements.

First, some brief background on the long road to our current graduation requirements. Back in 2014, the state passed House Bill 487, which gave students in the class of 2018 and beyond three pathways to a diploma. The primary route required students to earn points based on their scores on seven end-of-course (EOC) exams. The remaining two paths allowed students to earn a diploma either by completing career and technical education requirements or earning remediation-free scores on college readiness assessments.

These new requirements passed without much fanfare, and were considered to be rigorous but attainable standards. By 2016, though, several education groups had changed their tune. District leaders claimed that the EOCs were too rigorous, and that Ohio would soon face a “graduation apocalypse” because students weren’t capable of passing the assessments. The legislature responded by temporarily weakening graduation requirements, allowing students to earn a diploma based on non-academic measures like attendance, work experience, or community service. Advocates for high standards—including Fordham—pushed back, and a years-long battle ensued.

The debate finally came to a close in 2019, when the last state budget enshrined into law a new and permanent set of requirements that went into effect with the class of 2023. In addition to earning twenty credits in certain subjects, students must earn competency scores on two EOCs (one in math and one in English), fulfill career and technical education criteria, or meet military-readiness targets. They must also earn at least two diploma “seals,” which are designed to give students an opportunity to demonstrate skills that align with their particular interests. High schoolers are free choose which of the twelve approved seals they wish to pursue, but one of them must be state-defined (as opposed to a locally-defined seal with standards set by a district). Taken together, these new requirements set high but attainable expectations for students while also providing a variety of ways for them to demonstrate their competency.

Unfortunately, the recently proposed budget takes an axe to this hard-fought compromise that was put into law only two years ago. The bill makes several changes to graduation requirements, including to the social studies (referred to as citizenship) and science seals that students can earn. Under current law, a student can earn a citizenship seal in one of three ways:

The budget, however, would allow students to obtain a citizenship seal by earning a final course grade of B or higher in American history and American government courses offered by their high schools. Such grades would take the place of proficient scores on the EOCs for both these courses. The same change has been made to the science seal requirements. Rather than demonstrating proficiency on the biology EOC administered by the state, students need only earn a B or higher in one of a laundry list of science courses offered by their high schools, including chemistry, physics, physical science, advanced biology or other life sciences, astronomy, physical geology, or other earth and space science courses.

The upshot? Rather than asking students to demonstrate that they’ve mastered science and social studies content on an objective assessment that’s either aligned to state standards (EOCs), nationally recognized (AP or IB exams), or based on college-level content (CCP), state leaders only want to require a grade of B or higher in high school courses that students are already required to pass for graduation.

It’s unclear why this change was included in the budget. But it’s likely that this is yet another attempt by some state leaders to shy away from traditional academic measures. It doesn’t seem to matter that students have ten other seals from which to choose, and several of them don’t require passing a test. Never mind the research that indicates widespread grade inflation, or the relatively recent grade manipulation scandal in Ohio’s largest school district. Forget the intense pressure that’s put on teachers when their course grades become a key part of graduation standards. And certainly don’t pay attention to the fact that course grades and GPAs aren’t comparable across schools and districts, aren’t predictive of college performance for all students, and aren’t clearly linked to workforce success. State leaders would prefer for you believe that letting kids earn two of the seals they need to graduate based on a grade in whatever course their high school decides to offer is definitely in the best interest of everyone.

If a push to allow students to “demonstrate academic competency and mastery in ways beyond state standardized tests” sounds familiar, it should. It’s the same debate Ohio had for years over graduation requirements. This debate was supposedly settled during the last budget cycle, when a wide variety of stakeholders banded together to create a solution that—unlike a competing proposal offered by the State Board of Education—was objective, comparable, and valid. Editorial boards at the Columbus Dispatch and Akron Beacon Journal sung the praises of this solution. Legislators agreed on its merits, and so did the governor’s office. That’s how it became law in the first place. Why, then, does the newly proposed budget undermine such a hard-fought compromise? If cooperation is a worthy goal, then we successfully achieved it. It took us years, but we got here. And now, in one fell swoop, the budget would eviscerate a key component of the compromise.

But lest you get the wrong idea and assume this is just about politics, let me be clear: This provision is not in the best interest of kids. Weakening graduation requirements—even in seemingly small ways—is a slippery slope that ends with students earning meaningless diplomas that don’t represent mastery of the content and skills they need to be successful in college and the workplace. When diplomas become worthless, students pay the price. They enroll in remedial college classes that cost money, waste time, and decrease the chances of completion. They face a constant struggle to keep up with better-prepared peers. And they have difficulty finding and keeping well-paying jobs. High school diplomas are supposed to pave the way for kids to succeed. But when they don’t mean anything, they can’t.

The worst part about all of this, though, is that the students who are most likely to be impacted by this change are low-income students and students of color. Graduation data from the class of 2018—back when the State Board helped get those non-academic standards temporarily in law—suggest that Ohio’s low-income students used the weaker graduation options more frequently than their peers. There’s also a correlation between districts that enroll more students of color, either Black or Hispanic, and those that were more likely to allow students to graduate via the alternatives. The state of Ohio has a responsibility and a moral obligation to all its students to serve them well. But that obligation is particularly strong for economically disadvantaged and minority students, who face challenges that their white and affluent peers do not. This change is a massive disservice to the kids Ohio should be most committed to serving.

Graduation requirements reflect a state’s priorities and beliefs. If we believe that every student deserves a quality education that prepares them for the real world—whether its college or a job—then we have a responsibility to make sure kids are actually prepared. If we believe that our teachers and school leaders are the best in the country, then we shouldn’t be afraid of objective assessments of student learning. And if we truly believe all kids can learn, then we shouldn’t be afraid of high expectations.

Under pressure from the school establishment and teachers unions, Ohio lawmakers recently filed bills that seek to cancel state assessments this spring. If enacted, the legislation would cancel exams (subject to a federal waiver) for a second straight year, leaving Ohioans in the dark about where students stand academically amid major disruptions to their education.

Recognizing the need for up-to-date information, influential civil rights and education groups have opposed calls to bypass assessments yet again. Political leaders of both parties have done the same. On the GOP side, then Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos told states last fall to be ready to give state exams this year. (Whether her successor will follow the same path is TBD.) Here in Ohio, Governor Mike DeWine and Senate President Matt Huffman have voiced support for assessment as a way of seeing where kids are academically. Meanwhile, the Democratic chairs of the U.S. Senate and House education committees, Senator Patty Murray and Representative Bobby Scott, called testing this spring “a moral imperative”:

In order for our nation to recover and rebuild from the pandemic, we must first understand the magnitude of learning loss that has impacted students across the country. That cannot happen without assessment data. … Today’s announcement [regarding NAEP] makes 2021 administration of statewide assessments required by federal law a moral imperative.

Given the bipartisan backing—and support among parents—one might be surprised to see the pushback on state assessment this spring. What arguments are opponents making, and do they hold water? The following distills the major objections and then addresses those concerns.

Objection 1: It’s been a tough year and schools deserve a free pass. The 2020–21 year has indeed been like none other, and schools have faced significant challenges serving students amid the pandemic. Recognizing this, Ohio legislators have already waived report card ratings and consequences for the current school year, as they did for the prior year. No district or school will be penalized for its spring 2021 assessment results. All that’s being asked is that this year’s state tests be administered, so that parents and the public can see where students stand—a basic measure of transparency that will shine light on pupil achievement and help to guide recovery efforts.

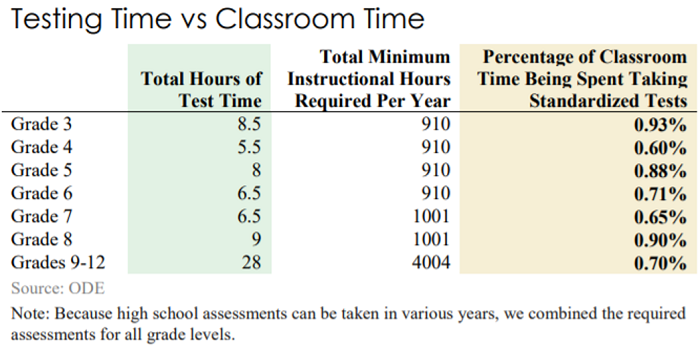

Objection 2: It’ll take away instructional time. Too much time on assessment is a common criticism even in normal circumstances. But opponents are ratcheting up their demands, arguing that zero time on testing is appropriate this year. To understand why this argument is flawed, it’s important to consider the facts about how much time is spent on state exams. The following table, taken from a recent report by the Auditor of State, reveals that students spend less than 1 percent of a school year on state exams. Of course, one might argue that thanks to remote learning, students may have received less than the typical 900 to 1,000 hours of instructional time this year. But it must be emphasized that the state did not waive its minimum hours requirement. During the pandemic, schools have been expected to make good faith efforts to meet them.

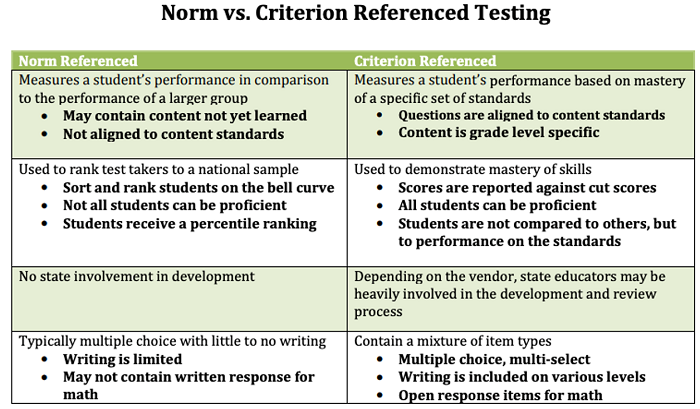

Objection 3: Diagnostic assessments are enough. In response to the argument that state exams are needed to gauge where students stand, opponents have put forward the notion that the diagnostic tests that many districts use are sufficient. These tests, such as the MAP and iReady, are of course important to educators. They offer a rapid assessment of student learning that allows teachers to tailor instruction and make course corrections during a school year. But diagnostic tests have significant limitations:

Objection 4: We already “know” the results. Some opponents of testing this year have claimed that it’s unnecessary because we already know the results. On average, it’s almost surely true that the typical student has suffered losses due to the disruptions. The averages, however, mask significant variation in the learning experiences—and outcomes—of students. Consider the recently released data from Ohio’s fall third grade ELA assessments. While the average third grade test score fell significantly, we also see that eighty-four districts and charter schools posted higher proficiency rates in fall 2020 versus the previous fall.[1] Twenty-eight of these schools had economically disadvantaged rates of more than 50 percent—bucking the conventional wisdom that low-income students are destined to lose ground. Meanwhile, among the eighty-eight districts and charters where proficiency rates slid more than 20 percentage points, twelve of them had had economically disadvantaged rates of less than 25 percent.

At the end of the day, no one truly knows how districts, schools, or students have fared over the past year. The danger of making policies or decisions based on assumptions about who is doing well or poorly is that students won’t be served well. Some may be consigned to remediation when they are actually ready to zoom ahead. Conversely, children struggling academically may get overlooked, allowing them to fall through the cracks. To ensure that decisions aren’t being made based on false assumptions, we need data about where each student stands against state academic standards.

* * *

With teachers being vaccinated and all schools expected to return to in-person instruction in March, there is no good reason to waive state exams for another year. High stakes won’t be involved in this round of assessment, schools should have ample time to administer them, and the results will provide information that cannot be achieved through local testing. Ohio should begin its “return to normalcy” with solid baseline information about student achievement in the midst of much turmoil.

[1] To be included in this count, a district or charter school needed to have at least twenty test takers and at least 66 percent of the number of test takers in fall 2020 versus fall 2019. This was done in an effort to remove schools with low test participation rates in fall 2020.

Last spring, Governor DeWine signed legislation that eliminated state tests and paused school accountability sanctions for the 2019–20 school year. Efforts by the education establishment to extend these changes through the 2020–21 school year began almost immediately. Their efforts failed during the lame-duck session in December, when legislators passed House Bill 409, which maintained exams for 2021 while wisely extending the accountability pause through the current school year.

But the anti-testing crowd is nothing if not tenacious. When the new legislative session started in January, they introduced several bills to eliminate testing in both chambers. One of these bills is Senate Bill 37 (SB 37). Here’s a look at its two key testing provisions, and why they aren’t the best path forward.

1. Seeking a federal testing waiver

Federal law requires all public schools to administer annual state assessments in certain grade levels and subjects. To bypass this requirement, Ohio would need to apply for and receive a waiver from the U.S. Department of Education. That’s what happened last year, when the state cancelled testing during 2019–20. But whether such a waiver will be available for the 2020–21 school year is still up in the air. Miguel Cardona, President Biden’s nominee for education secretary, has sent mixed messages about what he’ll do once confirmed, which should happen any day now.

Which brings us to Ohio. Nobody knows for sure if a federal waiver will be available, but SB 37 would require the state superintendent to “consult with stakeholders” about seeking a waiver and authorizes him to apply for one if it becomes available. This would pave the way for Ohio to cancel federally required state tests for the 2020–21 school year.

The education establishment has made several arguments in favor of waiving tests for a second straight year. But as my colleague Aaron Churchill recently noted, those arguments are flawed. The only accurate way to determine the extent of learning loss is to measure student learning against state standards. The resulting data won’t be used punitively. Thanks to HB 409, accountability consequences have already been put on pause. But schools will soon be open in-person, and it’s imperative that state tests be administered. The only way to ensure that at-risk students and those in underserved communities aren’t falling through the cracks is to have a single measurement that’s comparable and reliable across schools, subgroups, and geographic regions. Taking advantage of a federal testing waiver—should it become available—will make that impossible.

2. Cancelling tests that aren’t federally required

The sponsors of SB 37 also included a provision that would cancel state assessments that aren’t federally required. This includes social studies tests in fourth and sixth grade—which, under Ohio law, districts must administer even though the results don’t have to be reported to the state—as well as four end-of-course (EOC) exams, including English I, American history, American government, and geometry. (EOCs in English II, algebra I, and biology meet the federal requirements for English, math, and science tests in high school.)

Cancelling social studies exams won’t cause much disruption, as the results are not publicly reported. But the same can’t be said for cancelling EOCs, which are a critical part of Ohio’s graduation requirements. To address potential issues, SB 37 adjusts the state’s diploma requirements in two ways. First, it permits schools to grant a diploma to any student who is on track to graduate and has successfully completed the curriculum according to the school’s principal, teachers, and counselors. Second, it extends for an additional year a provision in current law that allowed students who were scheduled to take or retake an EOC but couldn’t because the exam was cancelled to use their course grade in place of an exam score to satisfy diploma requirements.

Reasonable people can disagree about the wisdom of using course grades in lieu of exam scores during this period of disruption. On the one hand, doing so opens the door for lowered expectations for high school students. On the other hand, there aren’t really any better alternatives if tests are cancelled. Getting lost in this debate, though, is the simple fact that if Ohio doesn’t receive a waiver and all other state exams are administered this spring, then it makes zero sense to cancel EOCs. We need comparable data and accurate information about potential learning loss for high school students just as much as we need it for their younger peers. Schools and families need to know if students aren’t college or career ready so they can intervene and remediate before students get out into the adult world. And while it’s true the stakes are higher because EOCs are tied to graduation requirements, it’s also true that Ohio students have several pathways toward a diploma. Those pathways include options that put a diploma within reach even if students don’t pass the required English and math EOCs.

***

The debate over pandemic-era testing is complicated. There are plenty of factors to consider, not the least of which is what’s in the best interest of students in the long run. If schools are able to safely reopen and stay open, then administering tests is crucial. It’s the only way to get the reliable and comparable data we need to funnel state funding and assistance to the places where they’re needed most.

With four years of student-level data available, a recent report from the College Board evaluates its own effort to boost the participation of traditionally-underrepresented students in computer science and other STEM fields.

In 2016, the College Board, with support from the National Science Foundation, launched a new Advanced Placement course called Computer Science Principles (AP CSP). While designed as a standalone—earning successful students college credit as with other AP offerings—the new course could also serve as a gateway to the longstanding Advanced Placement Computer Science A (AP CSA) class, and could provide a rigorous but less technical springboard into it for students long missing from such pathways.

AP CSP is described as “hands-on, project-based, collaborative learning” with students “exploring the big ideas of computer science and internet concepts.” Most importantly, teachers are given the flexibility to choose the programming language for their course, unlike AP CSA, which is limited to the college- and industry-standard Java language. There is no listing of which languages are utilized, but the popularity of simpler options such as Python, HTML, or Ruby make them likely candidates. And the end-of-course assessment process, in addition to a more traditional exam, comprises a unique performance task that students complete over the length of the course in which they create a program to solve a problem, enable innovation, explore personal interests, or express creativity. Students can collaborate with one or more partners during some parts of the task, such as the development of program code.

When it launched in 2016, the new class attracted more students than any other debut course in AP’s history. Approximately 65,000 U.S. students in the graduating class of 2019 completed the course and took the AP CSP exam. The College Board researchers studied 36,848 students, half of whom completed AP CSP by 2019 and half of whom were from the class of 2016 and did not have the opportunity to take AP CSP. Students were matched on academic performance and background characteristics. They looked at students’ course-taking behavior and college major choices, the latter data coming from the National Student Clearinghouse.

The analysts found that students taking AP CSP were more diverse than those taking the higher-level AP CSA and included a greater proportion of female, Hispanic, Black, and first-generation students. The new class was the first STEM-focused AP course for more than half of the Black students (68 percent), Hispanic students (59 percent), and first-generation students (60 percent). AP CSP students were more likely to go on to AP CSA and other AP STEM courses than similar students who did not have the opportunity to complete the new class. Black AP CSP students were three times more likely to enroll later in AP CSA than were their non-CSP peers. And AP CSP students were three times more likely than their non-CSP peers to declare computer science and other STEM majors in college, even if they only took the new course. That effect was boosted to 16.5 percent if AP CSP students went on to take AP CSA in sequence before college.

Opportunities in high-paying STEM jobs are expanding, and the number of jobs for computer science and research scientists is expected to grow 15 percent between 2019 and 2029, compared to 11 percent for all computer occupations and just 4 percent for all occupations. Thoughtful efforts to ease the entry into these education and career paths should be supported, especially ones that clearly work.

SOURCE: Jeff Wyatt, Jing Feng, and Maureen Ewing, “AP Computer Science Principles and the STEM and Computer Science Pipelines,” College Board (December 2020).

The return on investment for four-year college degrees is fairly well-established in terms of graduates’ employment and income trajectory, but the labor market outcomes for community college graduates are less well understood. Even though enrollment was trending downward even before the pandemic, America’s community colleges still confer over 1.5 million sub-baccalaureate credentials each year. These include associate degrees (which typically take two years to earn), long certificates (for programs at least one year in length), and short certificates (for programs less than one year in length). A recent research report published in the journal Education Finance and Policy aims to define the value of each of these credentials over time.

Researchers Veronica Minaya and Judith Scott-Clayton from Columbia University examine data on roughly 96,000 students who entered college in Ohio for the first time at age twenty or older, so that they can measure pre-college earnings, between fall 2001 and spring 2004. They look at the earnings and other outcomes over eleven years for students completing a terminal sub-baccalaureate credential. That is, they exclude students who subsequently enrolled in a four-year institution, so their effects are not capturing any value of transferring and/or completing a further degree. They use an individual fixed-effects approach that compares each student’s earnings after program completion to their earnings prior to enrollment. Non-completers—those who started a sub-baccalaureate program but never finished but are otherwise similar to completers—serve as a control group to account for any earnings growth that might have been expected over time regardless of credential attainment. The researchers control for student demographics, entry cohort, and degree intentions, since completers and non-completers could be on different earnings growth patterns for reasons unrelated to credential attainment. That said, their preferred model can’t completely account for things like motivation, which also correlates with credential attainment. Plus they do find that their results for men change somewhat when they relax the assumption that any differences between completers and non-completers of different credentials are fixed over time.

With those caveats in mind, Minaya and Scott-Clayton find that the value of an associate degree grows substantially after graduation, while the returns to a long certificate are flat over time in general and the returns to a short certificate are flat for women but grow somewhat over time for men. Returns on associate degrees are notably higher in recession years versus pre-recession years.

Associate degrees lead to improved outcomes relative to non-completers across a range of outcomes, including higher paying jobs, more stability in employment over time, and a greater likelihood of earning a living wage (defined as $30,000 annually). For example, the effect of completing an associate degree on the likelihood of earning a living wage is 25 percentage points for women, compared to a 13-percentage-point effect for a long certificate. Certificates, however, do pay off via the employment margin—meaning whether someone has a job at all—and a reduced likelihood of claiming unemployment benefits.

Of additional note: Two-thirds of sub-baccalaureate enrollments are in two fields—health and engineering. Researchers see that, for both men and women, the highest quarterly earnings gains upon graduation are in health-related fields, and these are even more pronounced for associate degrees as compared to certificates. For men, however, only 13 percent of associate degrees earned are in the health fields, compared to 40 percent for women. While this comparative decrease is likely not confined to sub-baccalaureate credentials, men completing associate degrees are clearly missing out on more lucrative career opportunities by not pursuing opportunities in the health sector.

The report closes by urging caution in terms of promoting certificates as equally valuable to associate degrees. Although long certificates have a payoff, it remains flat or declines over time, with the exception of engineering certificates for men.

Equally interesting (read: alarming) is the supposed speed by which students can acquire sub-baccalaureate credentials. Often touted as an expedient option for job advancement or retraining, it’s lost in reality. The average time to completion in the sample was four years for an associate degree, 3.6 years for a long certificate, and an astounding three years for a “short” certificate.

To make matters even more complicated, we know that geography also plays a role. Depending on where one lives, mean earnings can vary for workers with different levels of education. So it is all the more important that tomorrow’s high school graduates understand the options available to them and the likely value of those options in the future. Studies such as these address that need.

SOURCE: Veronica Minaya and Judith Scott-Clayton, “Labor Market Trajectories for Community College Graduates: How Returns to Certificates and Associate’s degrees Evolve Over Time,” Education Finance and Policy (August 12, 2020).

NOTE: On Tuesday, February 23, 2021, members of the House Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on House Bill 67 which would seek to waive testing in Ohio’s schools for the 2020–21 school year. Chad L. Aldis, Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy, gave opponent testimony before the committee. These are his written remarks.

Thank you for giving me the opportunity today to provide opponent testimony for House Bill 67.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy and Advocacy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

The last year has been incredibly challenging, as we’ve learned to live with Covid-19 and its many impacts. As we’re all well aware, education hasn’t been spared. Last March, students and teachers across the state were thrust into remote learning. Although a significant number of schools have reopened for in-person learning, the extended use of remote and hybrid models has greatly reduced the number of student-teacher interactions.

Recognizing these disruptions, the legislature passed House Bill 409 last December. HB 409 smartly waived state ratings and report cards for the 2020-21 school year and suspends consequences tied to them. This was absolutely the right thing to do and had our full support.

That being said, we believe going a step further and cancelling this year’s assessments would be the wrong decision for Ohio students. Here are four key reasons:

While I believe the case for testing this school year is strong, there have been some concerns raised. Here are a few of the most common:

***

No one truly knows how districts or schools—let alone individual students—have fared over the past year. The danger of making policies or decisions based on assumptions about who is doing well or poorly is that students won’t be served well. Some may be consigned to remediation when they are actually ready to zoom ahead. Conversely, children struggling academically may get overlooked, allowing them to fall through the cracks. Parents may fail to get the information they need to take action on behalf of their child. To ensure that decisions aren’t being made based on false assumptions or incomplete information, we need data from assessments about where each student stands against Ohio’s academic standards.

Thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony.