The consequences of a successful anti-voucher lawsuit

Earlier this year, the Ohio Coalition for Equity and Adequacy of School Funding filed a lawsuit aimed at eliminating the state’s EdChoice Scholarship Program

Earlier this year, the Ohio Coalition for Equity and Adequacy of School Funding filed a lawsuit aimed at eliminating the state’s EdChoice Scholarship Program

Earlier this year, the Ohio Coalition for Equity and Adequacy of School Funding filed a lawsuit aimed at eliminating the state’s EdChoice Scholarship Program. Over the next several months—more likely years—lawyers will argue the merits of this challenge in court. While it’s obviously premature to know how things will shake out, it’s important to consider what could happen if the lawsuit succeeds. Three of the biggest potential impacts deserve immediate attention.

The impact on kids and families

The most obvious—and most important—consequence of a successful anti-voucher lawsuit is its dire effect on EdChoice participants. For many parents, the school they believe best meets their children’s educational needs will once again be out of their financial reach. Those who used an EdChoice voucher to escape schools with a history of poor performance will be back to square one, searching for a better option that won’t break the bank. Others will return to districts that are satisfactory (or even good) academically, but for myriad reasons—like a lack of specific services or student behavior issues—weren’t a good fit for particular children. The fortunate few will be able to move to a different district, snag a seat at a charter or STEM school, or take advantage of scholarships and penny pinching to remain in private schools. But the vast majority won’t be so lucky.

For students, the adjustment could be difficult. Research shows that changing schools can have a negative impact on academic growth and achievement, especially if students transition to a lower-performing school. Temporary dips or difficulties might be an acceptable trade-off when families make a proactive choice, but that’s not the case when the choice is forced upon them. And that’s without even weighing the social and emotional impacts of a new school, new teachers, and new friends, none of which is easy even without a traumatic pandemic.

The impact on districts

The ultimate goal of this lawsuit is to get the 48,871 students who participated in EdChoice during the 2020–21 school year back into district schools. Public school advocates would view this as a massive victory—enrollments will increase, district coffers will swell (at least theoretically), and those pesky private schools won’t be able to “steal” kids and funds anymore.

But are districts really ready for all that? For many, enrollment increases will be small because the number of students participating in EdChoice is small. But in larger districts, the influx of new kids could be substantial. Consider Columbus City Schools, one of the districts named in the lawsuit. According to the most recent state report card, 6,720 students living in the district participated in EdChoice during 2020–21. If that program disappears, many of those students will return to their assigned public schools—and the district could see an enrollment increase up to 15 percent of its current student population.

This would have widespread impacts. School cafeterias will need to feed thousands more children. Principals will need to find classrooms and desks and textbooks and technology for an influx of new students with widely varying academic and social needs. And, most importantly, hundreds of new teachers and staff will need to be hired, or class sizes will have to increase.

Such adjustments require money. And given how often districts complain that EdChoice “steals” public funding, one might assume that eliminating the program would lead to a cash windfall for districts. But that might be illusory. Remember, vouchers are paid for using state dollars. Traditional districts, meanwhile, are funded by state and local dollars. On average, 45 percent of public school revenues are from local sources, and local dollars aren’t tied to student enrollments. That means if Columbus and other districts see a huge influx of students, the only additional funding they’ll receive is whatever the state funding formula allows. Nearly half of their budgets won’t adjust at all to the new enrollment count. District leaders are free to go to the ballot box and ask local taxpayers for more, of course. But given that many of those taxpayers are feeling the effects of price hikes and lingering pandemic impacts, that could be a big ask.

The impact on other voucher programs

From the standpoint of underserved kids and educational excellence, the most troublesome impact of a courtroom victory win is that it would open the door for challenges to Ohio’s other three voucher programs. They serve specific groups of children—two are limited to students with special needs, while the third is for children living in Cleveland—but they still allow families to use taxpayer dollars to attend private schools. If the lawsuit’s reasoning is sound, then these programs are just as unconstitutional as EdChoice. It stands to reason, then, that in time the state would need to sacrifice all voucher programs, including those that serve over 11,000 children with special needs. Families who found that traditional public schools were not equipped to handle the unique needs of their students but couldn’t afford to pay out-of-pocket expenses for the right care will be forced to return to the assigned public schools that weren’t meeting their needs in the first place. That’s immoral and inexcusable.

***

As the anti-voucher lawsuit travels through the courts, the focus will be on legal and constitutional considerations. Yet we must not forget the real-world consequences for thousands of Ohio families, students, and taxpayers should the plaintiffs prevail. Those shouldn’t be ignored.

Almost ten years have passed since Ohio lawmakers enacted early literacy reforms that aim to ensure all children read fluently. Based on pre-pandemic state exam trends, the “third grade reading guarantee” seems to be encouraging a stronger focus on literacy and pushing achievement in the right direction. Yet despite the promising signs of success, policymakers can’t afford to let up. In fact, given the pandemic-related learning losses, they need to double down on the state’s early literacy efforts.

In a recent piece, I examined the retention provision that requires schools to hold back third graders who do not meet reading standards and offer them additional help. While some are clamoring for its removal, doing so would be a huge blunder. By reverting to the disastrous practice of “social promotion,” poor readers would once again be allowed to fall through the cracks. They would pass to fourth grade, and likely beyond, lacking the foundation needed to tackle more challenging material.

But the retention requirement is just one part—albeit a critical one—in the overall package. Several other important policies also comprise Ohio’s early literacy law. This post reviews the guarantee’s diagnostic testing, parental notification, and reading improvement provisions; at the end I’ll suggest some areas for improvement. Note, too, that we’ll cover the intervention requirements for retained third graders in a future installment.

Diagnostic assessments

Under the reading guarantee, schools must assess grade K–3 students annually every fall. In kindergarten, schools may use the language and literacy section of the statewide Kindergarten Readiness Assessment as the diagnostic or administer one of sixteen state-approved vendor assessments. In grades 1–3, schools may fulfill the requirement via vendor or a state-designed diagnostic assessment. These tests gauge whether students are reading on grade level—i.e., on or off track.[1]

The diagnostic is a necessary screening tool that encourages timely intervention, even prior to third grade. But we ought to ask whether these tests are accurately identifying struggling readers. Remember, there’s no single statewide diagnostic test, so schools could be choosing assessments that are weakly aligned with state reading standards and risk overlooking children who need extra help.

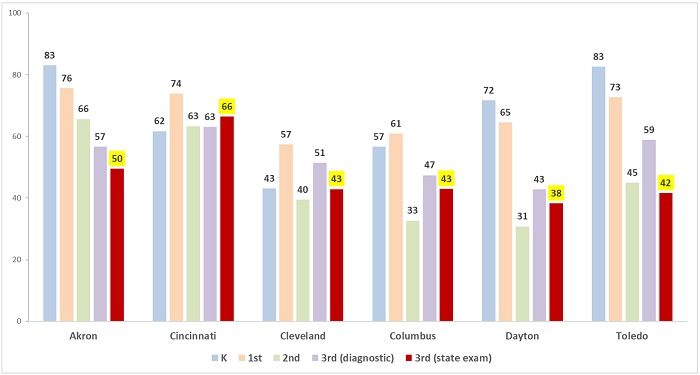

When examining pre-pandemic data, there is some reason for concern. Consider figure 1, which displays K–3 on-track percentages in Ohio’s largest urban districts and their third grade proficiency rates. In four districts—Akron, Columbus, Dayton, and Toledo—the on-track percentages in grades K–1 are noticeably higher than their third grade reading proficiency rates, by about 15 to 40 percentage points. Then they fall significantly in second grade, and by third grade they track more closely to proficiency rates. This may indicate that the kindergarten and first grade assessments in these districts are giving a faulty assurance that students are on track when they really are not.

Figure 1: Grades K–3 “on-track” percentages in reading (fall 2019) versus third grade ELA proficiency rates (spring 2019), selected districts

Source: Ohio Department of Education, 2019–20 K–4 literacy report and 2018–19 district achievement data.

Irregular data are not limited to these districts. In fact, some Ohio districts reported all or virtually all of their children as on track in reading, yet had low third grade proficiency rates. For instance, Waverly and Paulding school districts posted 100 percent on-track rates in all grades K–3 on fall 2019 diagnostics, but had third grade proficiency rates of 63 and 76 percent, respectively. There are some oddities in the other direction, too. Wooster and Copley-Fairlawn, for example, reported that less than 10 percent of grades K–3 students were on track, but their third grade proficiency rates were 75 and 90 percent in spring 2019.

Overall, there’s enough inconsistency in the data to question whether the diagnostic tests are accurately identifying students as being on or off track. Are some districts using tests that yield “false negatives”—failing to identify a reading deficiency when one exists? Conversely, are other tests more prone to “false positives”? Accurate diagnostic tests are crucial, as those results drive decisions about whether students receive extra reading supports.

Parental notification and improvement plans

Under statute, a school district must do two things when children are deemed off track via reading diagnostics:

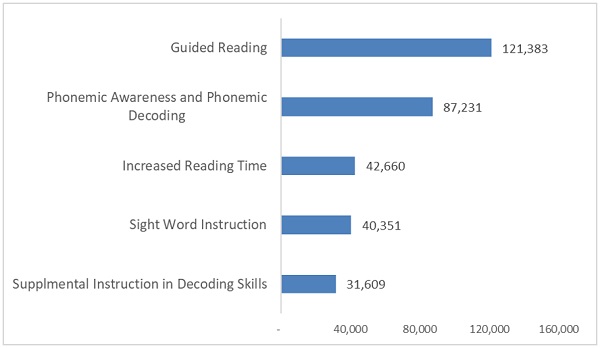

Per state law, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) reports the types of interventions that students with an improvement plan receive. Figure 2 displays the five most frequently reported interventions for the 2020–21 school year (the numbers are mostly similar to 2019–20). What’s noticeable are the broad intervention categories. For example, what exactly happened during “increased reading time”?

Figure 2: Most frequently reported interventions for off-track readers, 2020–21

Source: Ohio Department of Education

To its credit, ODE has recently overhauled this reporting system, so that schools must now report literacy interventions with greater specificity. Gone are ambiguous terms, and instead, schools will now report using categories such as “explicit intervention in phonemic awareness” and “explicit intervention in vocabulary,” terms that appear to be well-defined by ODE and are referenced in its statewide literacy plan. The new list does include a few highly questionable but, unfortunately, still-used approaches, though ODE flags those as not being part of its literacy plan (e.g., the three cuing system). Moving forward, this change is a step forward in transparency and should yield a clearer picture of schools’ efforts to address reading deficiencies in the early grades.

Policy refinements

The diagnostic testing requirement, along with mandatory parental notification and improvement plans for off-track readers, are core strengths that should remain firmly in place. Yet policymakers could also consider fine-tuning these policies to better ensure they are being well-implemented. Here are five ideas that would strengthen these provisions.

The ability to read fluently is crucial to lifelong success. The third grade reading guarantee has the right goals, and the policy building blocks are in place to make certain that children acquire foundational reading skills. But to truly fulfill its promise of being a “guarantee,” lawmakers need to further strengthen these policies to ensure that all struggling readers in grades K–3 receive the extra help and support they need.

[1] The fall diagnostic tests gauge reading achievement against a student’s previous grade standards. For example, a fall second grade test measures performance against first grade standards. The fall version of the state ELA exam cannot be used as the third grade fall diagnostic test (the state exam is given about a month later).

[2] While not, to my knowledge, used in Ohio law, the term is used in Colorado’s early literacy law and is key to ODE’s statewide literacy plan.

[3] There is language directing ODE to annually report “if available, an evaluation of the efficacy of the intervention services provided.” In its last two annual reports—the only ones posted online—ODE notes that it could not undertake an evaluation due to data limitations.

In March of 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic was just beginning its deadly sweep across the United States, Ohio became the first state to close all K–12 schools. Nearly two weeks later, the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, or CARES Act, was signed into law. Approximately $30 billion of this stimulus package was reserved for schools, and Ohio received a whopping $489.2 million in the form of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund.

Ninety percent of these funds were distributed directly to schools using Title I formulas. But the remaining 10 percent—nearly $49 million—was set aside to pay for state-level efforts to support schools. One such effort was RemotEDx, a statewide initiative aimed at helping schools “enhance, expand, and more effectively scale high-quality remote, hybrid, and blended education models.” Given that every school in the state—public and private alike—was operating fully remote at the time, investing $15 million of the set-aside in virtual learning improvements was a smart move. But what, exactly, is RemotEDx? Let’s take a closer look at some of its key components.

Coordinating Council

RemotEDx is a collaborative effort, but its overall direction is overseen by the Coordinating Council. The Council consists of leaders and educators from both the public and private sphere, and includes representatives from district schools, charter schools, the State Board of Education, the Governor’s office, BroadbandOhio, Education Service Centers (ESCs), the Management Council, Information Technology Centers, philanthropy, business, higher education, PBS stations, and libraries. Together, these members develop and approve criteria for high-quality remote education models included in the Exchange (more on this later), facilitate discussions on how to better align and coordinate remote education across the state, and review project updates, outcomes, feedback, and proposed improvements. The Council was also responsible for codesigning the various components of the initiative, including Connectivity Champions and Support Squad.

Connectivity Champions

This group does exactly what its name suggests: provides boots-on-the-ground assistance to overcome internet connectivity issues. Primary goals include ensuring all pre-K–12 students have home internet access, helping schools overcome technology barriers, engaging with vendors to troubleshoot and solve problems, and collaborating with the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) and Ohio’s Information Technology Centers. The Management Council, which coordinates and supports the Ohio Education Computer Network, is also a key partner.

Since the creation of RemotEDx, the Connectivity Champions have directly engaged with schools and families across all eighty-eight Ohio counties, and have provided more than 600 connectivity or technology related services. These services include connecting families to reliable and sustainable broadband service, supporting schools with the BroadbandOhio Connectivity Grant, and collecting data from 592 traditional public districts, joint vocational school districts, and charter schools as part of the Opportunity to Learn survey. Going forward, the Connectivity Champions will play a key role in coordinating state and federal broadband programs, including the $3.2 billion Federal Communications Commission Emergency Broadband Benefit Program and $7.2 billion Emergency Connectivity Fund.

Support Squad

The Support Squad is made up of staff from each of Ohio’s fifty-one ESCs who were selected by ESC superintendents in December 2020. Collectively, they support schools by identifying and compiling technology, content, instructional, and vendor information that supports remote, hybrid, and blended learning. They also identify and provide schools with high-quality professional development opportunities. Members of a smaller subset of the squad, known as the Concierge Team, are assigned to support specific regions of the state. They do so by working directly with ESC-identified experts and service providers, responding to help requests submitted online, and procuring professional development experiences and content for teachers as well as supports for students.

Since its launch in late summer 2020, the Support Squad has served over 10,000 educators through targeted training opportunities and provided thirty-two ESCs with training on how to seamlessly integrate resources and services available through RemotEDx. Going forward, the Support Squad plans to provide ongoing professional development and coaching.

The Exchange

The Exchange is a “one-stop shop” for Ohioans—both educators and families alike—to explore the resources, services, and tools available through RemotEDx. The website, which is powered by INFOhio, highlights high-quality remote education platforms, standards-aligned instructional materials and curricula, and professional development resources. It contains a page for parents and caregivers, as well as one for educators, and parents and teachers alike can peruse the Curriculum Library, which offers instructional resources, collaboration and creation tools, curriculum and instructional reviews from EdReports and RemotEDx reviewers, and links to other useful sites.

Since its launch, the Exchange has gathered more than 80,000 standards-aligned instructional materials from Ohio content providers and organized them into statewide curriculum repositories. These resources have been used in almost every county in Ohio, forty-four other states, and twenty-six countries. Going forward, the state plans to leverage RemotEDx and the Exchange, as well as other programs, to develop peer-to-peer tutoring, technology supports, and a computer science curriculum aligned to Ohio’s learning standards.

Funding Opportunities

Under the umbrella of RemotEDx, Ohio has created several funding opportunities for schools. For example, the state awarded seventeen subgrants worth up to $150,000 each to nonprofit and community-based organizations partnering with schools to improve remote teaching and learning opportunities for underserved students. ODE also partnered with Philanthropy Ohio to fund the Ohio Collaborative for Educating Remotely, or OCER, which offered two rounds of grants aimed at helping schools improve remote education practices and outcomes. The first round awarded $3.1 million to twenty-eight projects that reached more than 788,000 students, and the second round awarded just over $2.6 million to twenty-nine projects that reached over 107,000 students.

RemotEDx also tackled the sudden drop in the number of Ohio students earning industry-recognized credentials (IRCs). In 2020, 46,569 students earned an IRC. That’s a sizable number, but it’s significantly smaller than the 62,210 students who earned credentials during the previous year. To help bring these numbers back up, RemotEDx awarded eleven subgrants to Business Advisory Councils, industry sector partners, and other eligible entities that will serve nearly 11,000 students, spearhead awareness and outreach campaigns that reach all eighty-eight Ohio counties, and provide training to more than 10,000 educators.

***

The vast majority of students and educators are back to full-time, in-person schooling. But that doesn’t mean that supplemental and high-quality remote, hybrid, and blended learning opportunities need to fall by the wayside. The state has already said that it will use future federal funding to “expand the footprint” of RemotEDx and reimagine the “future of education in Ohio.” That’s good news so long as state leaders transparently track outcomes and ensure that the services and opportunities offered to students and educators are high quality.

Folks who have “tutoring” as the hoped-for winning square on their post-Covid bingo card will want to pay close attention to a recent report detailing a field experiment in virtual tutoring. A group of researchers led by Sally Sadoff of the University of California San Diego created the pilot program and tested its efficacy via a controlled experiment. While the price tag was low, the academic boost observed was negligible, and any effort to scale it up will require much that’s still in short supply more than two years into the pandemic.

In the experiment, sixth- to eighth-grade students from one middle school in Chicago Heights, Illinois, were randomly selected to receive virtual tutoring from college students via the CovEducation (CovEd) program. CovEd was created during the early days of the pandemic in 2020, intended to support K–12 students in need of academic and social-emotional support. Tutors were college students, specifically recruited from “top-tier research universities,” who worked as volunteers (hence the low cost of the effort). A total of 230 tutors participated in the pilot from forty-seven institutions. About three-fourths of them were women; 40 percent were White, 34 percent were Asian, 20 percent were Hispanic, and 5 percent were Black. About 70 percent were science or engineering majors. Prior to the start of the program (March 2021), CovEd provided tutors with a three-hour training on pedagogical techniques, relationship building, and educational resources. During the program, CovEd offered tutors weekly peer mentoring sessions to troubleshoot challenges, share best practices, and build community.

Nearly 100 percent of Chicago Heights Middle School (CHMS) students were from low-income households; almost two-thirds were Hispanic, and just less than one-third were Black. Prior to the pandemic, just one quarter of students in the school were meeting grade level standards in math and reading. In February 2021, CMHS students were offered a choice to remain fully remote or participate in a hybrid model where they attend school in person part-time and learn remotely part-time. Only students who chose the hybrid option (approximately 58 percent of the total school population) were eligible to participate in the pilot. A total of 560 students were involved in the experiment, randomly assigned to either treatment (264) or control groups (296). Control group students participated in regular advisory period activities whereas treatment group students received tutoring. No demographic breakdown of students in each group was provided in the report. Treatment students were offered thirty minutes of one-on-one virtual tutoring twice per week—one virtual session while in person at school and another while remote at home. Thus, over the twelve-week program, students had a maximum of nine hours during which to attend tutoring. However, students were added to the treatment group in three waves, and those who joined in later weeks had fewer participation opportunities available.

Glitches occurred right off the bat. Eighteen percent of those assigned to the treatment group did not attend a single minute of tutoring. On average, participants attended just 3.1 hours. Low take-up was ascribed to weak overall attendance during this “transitional period” from fully-remote to hybrid learning, a common story in schools across the country. Student achievement in math was measured via the Illinois Assessment of Readiness test—the state’s standardized test—and in reading via iReady, a formative assessment used to track student progress. Bottom line: The pilot program produced consistently positive but very small and statistically insignificant effects on student achievement on both tests compared to the control group.

The researchers run intent-to-treat models and report that if more students had spent more time on tutoring, they would likely have done even better on the tests. Even though this seems somewhat obvious—the same could likely be said of attending more actual school—they use it as the basis for their contention that the tutoring program could be scaled to produce stronger academic outcomes. However, it must be noted that there was an extensive social-emotional aspect to the pilot program that is entirely undocumented here. Having no data on how much time was actually spent on academic support in each session versus building relationships or other SEL priorities muddies the water in terms of ROI.

Those who led the pilot remain optimistic about scaling it up, but that won’t be easy. The supply of free college student labor is finite, and even more finite when limited to research universities. And ardor for the remote option utilized here will wane as the “old normal” reasserts itself. And student absenteeism—an ongoing problem with regular school—will continue to dog any voluntary program such as this one. It seems likely that the kids who might have the greatest need of tutoring are most apt to skip, or be unable to participate in, those sessions. All of these together could serve to keep the tiny academic effects seen in the pilot at exactly the same level—at a higher cost—in a larger effort.

SOURCE: Matthew Kraft, John List, Jeffrey Livingston, and Sally Sadoff, “Online Tutoring by College Volunteers: Experimental Evidence from a Pilot Program,” The Field Experiments Website (February 2022).

In a laudable quest to boost the number of adults with postsecondary credentials, a number of states—including Ohio—are focusing time and treasure on former students who have earned some college credits but have not yet completed a degree. These “some-college-but-no-degree” individuals (SCNDs) are considered to be the easiest to persuade to return and the likeliest to see an economic benefit from completion. A new working paper testing this idea returns some rather disappointing results.

Data for the study come from detailed administrative records for students enrolled in credit-bearing courses at any of the Virginia Community College System’s (VCCS) twenty-three campuses. State unemployment insurance records and the National Student Clearinghouse provide labor force data and information on postsecondary credentials earned at non-VCCS institutions, respectively.

The initial sample comprised 376,366 first-time students who enrolled in VCCS for any length of time between the 2009–10 and 2013–14 academic years but did not complete a credential or degree. Because of their interest in adults who are most likely to return and complete a credential, the researchers restricted their sample to students who had accumulated at least thirty college credits and who had a minimum GPA of 2.0 during the term immediately before leaving VCCS—a relatively high-achieving group as compared to the typical college dropout. The analysts also focused on those who remained out of VCCS for a minimum of three years, as analysis indicated this was a good statistical demarcation between those temporarily leaving college and those whose separation was more likely “permanent.”

The final sample consisted of 26,031 individuals who, believed the analysts, had the greatest potential to finish their post-secondary education. The comparison group, referred to as “Grads,” are students who left VCCS with a degree between the 2009–10 and 2013–14 academic years and had no subsequent enrollment at any other institution within three years of their graduation. (This excluded students who finished an associate degree and went on to a four-year university.) The Grads sample consisted of 28,795 students with demographics similar to SCNDs, although Grads were more likely to be White and female. Grads were also approximately two years older when they left VCCS, and had earned approximately 1.5 times the number of credits than their SCND peers.

Overall, following their separation from the Virginia community college system, SCND individuals were less likely to be employed and, conditional on employment, earned less than students who graduated during the same time period. However, these differences were relatively modest—typically less than 5 percent lower than Grads’ employment or wage mean, after controlling for other observable differences. It is likely that the researchers’ focus on higher-achieving SCND individuals, most of them almost two-thirds of the way to an associate degree, is having an impact on the paper’s employment and earnings outcomes.

SCNDs who remained employed also earned steadily increasing wages over time, characterized by the researchers as a significant disincentive to returning to school. Approximately 50 percent were employed in every quarter of the third year following their departure from community college, and a substantial majority (approximately 80 percent) were working in fields where the earnings differential between Grads and SCNDs was narrowest. Even among SCND students whose earning differential was widest compared to Grads—those who might want to return to better their earning potential—the vast majority were working in healthcare-related fields. Those majors are typically oversubscribed in community college, creating another strong disincentive for those SCNDs to return even if they wanted to.

Collectively, these employment, wage, and enrollment patterns suggest to the authors that there are relatively few SCNDs (approximately 3 percent) who could easily re-enroll in fields of study and reasonably expect a sizable earnings boost upon finally completing a degree. These findings mitigate against the extensive efforts of some states to convince SCNDs to return. However, while this is likely true as far as this study goes, other such analyses have gone farther. In those studies, by including shorter-term credentials and four-year degrees as outcome measures, both the number of SCNDs who stand to benefit from additional postsecondary education and the possible premium to be earned appear larger.

As long as the focus remains set on the best possible outcome for SCND individuals—rather than simply having folks earn credentials for its own sake—the wider the options for completion, and the more substantial the support to get there, the better.

SOURCE: Kelli A. Bird, Benjamin L. Castleman, Brett Fischer, and Benjamin T. Skinner, “Unfinished Business? Academic and Labor Market Profile of Adults With Substantial College Credits But No Degree,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (January 2022).