Does the updated Cupp-Patterson plan treat charter schools fairly?

The latest iteration of the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan was recently unveiled in an amendment to House Bill 305 and the introduction of a

The latest iteration of the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan was recently unveiled in an amendment to House Bill 305 and the introduction of a

The latest iteration of the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan was recently unveiled in an amendment to House Bill 305 and the introduction of a Senate companion bill. The plan still faces plenty of questions, including how to pay its $2 billion per year sticker price. One question that’s flying a little below the radar is how the latest version treats charter schools. If you recall, the initial plan gave choice programs the cold shoulder, most notably by freezing charter funding after just two years while allowing district funding to continue rising. What does the revised version of the Cupp-Patterson plan have in store for charter schools? Let’s take a look.

(Of note, this piece doesn’t look at private-school scholarships, as significant changes were recently made to these programs. We’ll save them for another time.)

Issue 1: Funding equity

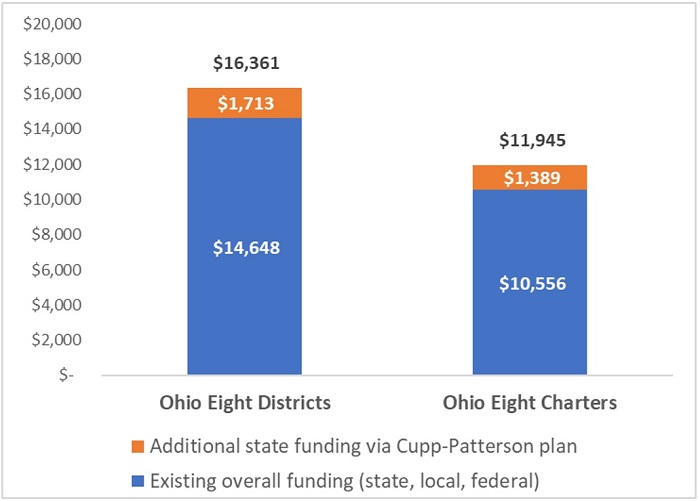

Ohio’s public charter schools have long received the short end of the school-funding stick. In the Ohio Eight—the cities where a large majority of charters are located—brick-and-mortar charters receive on average roughly $4,000 per pupil less than districts, even though they serve students of similar backgrounds.[1] Figure 1 shows that the Cupp-Patterson plan would not narrow these yawning funding gaps. In fact, it would widen them. Under a fully-funded plan, the Ohio Eight districts would see an average increase of $1,713 per pupil, versus $1,389 per pupil for charters.[2] Although charters enjoy increased funding in absolute terms, they would continue to lose ground when compared to their nearest districts, further limiting their ability to compete for talented teachers or offer comparable academic and non-academic supports.

Figure 1: District and charter per-pupil funding in the Ohio Eight cities

Note: This figure displays the average overall funding per-pupil across the Ohio Eight districts and the brick-and-mortar charter schools located in those districts in FYs 2015-17 (calculations are here). The additional state funding represents the average increases under a fully-funded Cupp-Patterson plan. The estimated increases for individual Ohio Eight districts and charter schools vary quite widely, from $652 to $3,009 per pupil on the district side and -$82 to $3,665 per pupil on the charter side.

To level the playing field for all educational models and encourage true “educational pluralism” in Ohio, a much different approach to school funding reform is likely needed. But there are three ways that the Cupp-Patterson framework could be tweaked to make funding more equitable for the students attending charter schools.

First, the plan should ensure that charter funding amounts are calculated in the same way as districts. The Cupp-Patterson plan employs extensive calculations, based on pupil-to-staff ratios, salary data, and more, that yield the “base cost” of educating a typical student. Those costs, which vary by district, are then used to determine state funding amounts. The initial version of the plan didn’t apply the base cost formula to charters; they instead received fixed amounts. To the extent that districts are funded via a base cost model, the updated plan rightly moves charter funding into this framework.[3] Yet the plan still deviates from it in two ways: (1) charters’ base costs are reduced by 10 percent in three of the four components of the calculation, and (2) their costs are calculated in three components via statewide averages rather than the ratio and salary calculations that apply to districts.[4] Bottom line: Both of these modifications, made without an obvious policy rationale, would reduce the base costs of charters and increase the funding gap between charters and districts.

Second, the base cost model should better reflect the costs of operating high schools. General education charter high schools tend to receive relatively small funding bumps. Some receive estimated increases of less than $500 per pupil—and Dayton Early College Academy, one of the most highly respected urban schools in the state, actually loses $82 per student. This is likely due in part to the base cost model that calls for fewer teachers per student in grades nine through twelve, hence lowering the assumed costs. Such an approach might be okay for entire districts, which can allocate centralized resources to high schools, but it hurts standalone high schools that may actually face higher costs than elementary or middle schools.[5] For instance, high schools may need to purchase expensive science equipment, pay higher salaries to attract teachers, fund more extracurriculars and athletics, or offer college and career counseling. Overall, the base-cost framework may need to be revisited to better reflect the higher costs of a high school education. Of course, that could further inflate the plan’s already hefty price tag.

Third, the Cupp-Patterson plan is mum on the future of the supplemental funding program for quality charter schools that was first implemented in FYs 2020–21. With the backing of Governor DeWine, this $30-million-per-year initiative provides up to an additional $1,750 per economically disadvantaged student to charters that qualify based on academic performance. These dollars help narrow funding gaps, provide extra resources that enable charters to serve more students, and make Ohio a more attractive locale for excellent national charter networks. The plan should include—and make permanent—this valuable charter funding initiative.

Issue 2: Deduction versus direct payment

Instead of deducting dollars designated for charter students from districts’ funding allocations—i.e., the current “pass through” method—the Cupp-Patterson plan would require the state to pay charters directly. This would be a step forward for reasons explained here. The plan, however, lacks one crucial detail. There needs to be clear statutory language that ensures charters are funded through the main, multi-billion-dollar K–12 education appropriation in the state budget, not via a standalone line item that exposes them to budget cuts or even veto. This could be done by simply copying existing statutory language used to fund school districts and joint vocational districts. In sum, any move to direct funding, whether that’s via the Cupp-Patterson plan or otherwise, must ensure that charters are paid through the same pot of money that funds school districts.

Issue 3: The long run

The initial version of the Cupp-Patterson plan called for a periodic updating of districts’ base costs so that their funding levels would adjust with inflation well into the future. The latest version, somewhat surprisingly, scraps the provisions calling for future adjustments of base costs and instead creates a School Funding Oversight Commission that would make recommendations about how to adjust the formula in the years to come. Unfortunately, charters would not be represented on the commission—eight school district officials would be appointed, along with legislators and parents—leaving them devoid of a voice in matters of funding. If such a commission is deemed necessary, charters should have a seat at the table. And speaking of bureaucratic exercises, the revised Cupp-Patterson plan continues to call for a needless study of charter schools’ operating costs. If the plan has captured the cost of educating a typical student—as its developers claim to have done—then that model should apply to charters just the same as districts.

***

Although the revised Cupp-Patterson plan is an improvement from its predecessor, it still doesn’t treat charter schools fairly. Instead, it would exacerbate existing inequities by once again treating charters—despite their superior performance—as second-class public schools. Version three of the plan, should there be one, must right these wrongs.

[1] The “Ohio Eight” refers to Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown.

[2] The updated version of the Cupp-Patterson plan calls for a six-year phase-in of the funding increases, starting in FY 2022. Each year’s phase-in percentage would be determined by future General Assemblies. The phase-in policy for charters and districts would be the same during the six-year period.

[3] E-schools are included in the base cost model. However, continuing current policy, they do not receive several “categorical” funding streams (e.g., extra allocations for economically disadvantaged students). The estimated increases for e-schools under a fully funded Cupp-Patterson plan range from $425 to $1,028 per pupil.

[4] The base-cost calculations in the Cupp-Patterson plan are broken into four components: 1) Teacher, 2) Student Support, 3) Building Leadership and Operations, and 4) District Leadership and Accountability. The 10 percent reduction and statewide averaging apply to the latter three components of charter schools’ base cost calculations. On average, those components make up 42 percent of the overall base cost.

[5] Ohio’s seven STEM public high schools, which are funded much like charter schools, also receive smaller funding increases. Under a fully funded plan, they receive estimated increases of between $302 and $858 per pupil.

In the last week, there’s been a flurry of discussion around what the incoming Biden administration could do for student loan borrowers. While much of the discussion has centered on loan forgiveness via an executive order, the campaign’s policy platform for education beyond high school outlines several additional ideas that could have an enormous impact on current and future borrowers. These include making public colleges and universities free for all families with incomes under $125,000, doubling the maximum value of Pell Grants, and improving income-based repayment programs.

The most significant changes, though, would be to the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program. Created in 2007, this federal program was designed to reward workers who chose careers in the public service sector, including teachers. (This program is different than federal TEACH grants, which help aspiring teachers willing to work in high-poverty public schools to pay for college and, as reported by NPR, have been a bit of a disaster for borrowers.) To be eligible for forgiveness through PSLF, borrowers must make 120 monthly payments, work full-time for a qualifying employer for ten years, and be enrolled in a qualifying repayment plan. In return, they can have all of their loans forgiven.

The first cohort of eligible borrowers should have started receiving loan forgiveness through PSLF in 2017. But almost none did. In the fall of 2018, the New York Times wrote that only 96 out of 28,000 applicants were approved—a rejection rate of 99 percent. By the fall of 2019, things hadn't improved. Congress attempted to fix the program, but their fixes resulted in another 99 percent rejection rate.

These high rates of rejection were due to a plethora of issues: complex rules, a lack of guidance from the U.S. Department of Education on how to administer the program, and a lack of outreach to borrowers (the Government Accountability Office noted in its report that many borrowers didn’t seem to understand or be aware of the program’s requirements). The program’s reliance on the term qualifying—which is used to identify both employers and repayment plans—is complicated, and borrowers are often given incorrect or incomplete information. As a result, there are countless stories of teachers who have spent years dutifully paying their loans and being assured by their loan servicers that they were on track toward forgiveness, only to be rejected when they applied. The Department of Education unveiled some additional changes to the program earlier this year, but the general consensus seems to be that it’s still a bureaucratic nightmare.

It’s unclear how many of these rejected applicants were teachers, though it’s likely that there are plenty of them, given that one of the nation’s largest teachers’ unions is suing the U.S. Department of Education. Like most professions, teaching “backloads” compensation and benefits: The longer a teacher works, the more they receive. So early-career teachers are struggling to pay their student loans during the point in their careers when they’re making the least amount of money (and might also be trying to purchase their first home or raise a family). Meanwhile, under PSLF, if public sector workers like teachers leave public sector employment before the program’s ten-years requirement, they have no loan forgiveness option at all, regardless of their previous years of service. Add the dismal rejection rate of PSLF to the equation, and it’s not hard to see how sky-high student debt might discourage prospective teachers just when we need them the most.

Fortunately, the president-elect has a plan to address some of these issues. According to the campaign’s higher education policy platform, the administration will work with Congress to create a new, simpler program that would offer $10,000 of undergraduate or graduate student debt relief for every year of national or community service, up to five years. The plan specifically notes that it will be available for individuals working in schools (presumably public schools, including charter schools, though it doesn’t specify), in addition to those who work for government and nonprofit organizations. Borrowers will also be automatically enrolled in the program, a change that addresses one of the primary failings of PSLF—that borrowers were often enrolled in the wrong repayment plans and found out too late that they weren’t eligible for forgiveness.

It’s not directly stated, but it appears that this new program is intended for future borrowers. So, what about current borrowers? The Biden platform notes that the administration intends to secure passage of the What You Can Do For Your Country Act, which was introduced in 2019, to overhaul the PSLF program in several ways:

Of course, it’s important to recognize that as encouraging as these plans are, they hinge on the administration’s ability to work with Congress. That might be easier said than done. There’s some debate about whether the president-elect can sidestep Congress and use an executive order to address student debt in some capacity, but it’s unclear whether he will. One thing is for sure though: In the wake of a pandemic that’s been devastating to the education sector in so many ways, these are exactly the kinds of policies that the teaching profession needs. Here’s hoping the folks in D.C. figure out a way to strike a deal and give public servants the debt relief they were promised over a decade ago.

Back in July 2019, Ohio lawmakers suspended the school funding formula, the policy mechanism that is supposed to drive state money to school districts and public charter schools. Having just taken office, Governor DeWine was unlikely to wade deep into school funding debates and in fact focused primarily on a proposal to boost funding for student wellness. With respect to the formula itself, Statehouse legislators generally expressed an unease with it but a lack of consensus around a replacement seems to have led them to hit the pause button. Hence, districts’ state funding amounts in FYs 2020–21 have generally been the same as they received in FY 2019.[1]

With the election over, state legislators will soon be turning their attention to the next biennial budget for FYs 2022–23. The Cupp-Patterson plan will surely continue to receive attention as a potential funding formula, but even if it doesn’t pass, legislators should make it a priority to get Ohio back to a formula-driven system. While the “formula” may sound wonky and technocratic, it also serves vital purposes. Let’s review in more detail why a functioning formula is so important.

First, Ohio’s formula works to ensure that funding is based on student enrollment. Ohio’s funding formula (as it existed in FY 2019) is purposefully designed to send state money to districts and charters based on their current pupil enrollments. This feature adheres to the principle of funds following students. In addition to funding based on overall enrollments, Ohio’s formula also ties additional dollars to students in specific categories: students with disabilities, English language learners, economically disadvantaged pupils, career-and-technical education students, and students in grades K–3. These “categorical” funding streams ensure that schools receive extra resources when they serve students who need additional supports.

There’s one caveat to mention, however. While it’s fair to say that the formula deployed in 2019 was generally based on pupil enrollment, it deviated from this model through the use of caps and guarantees. Because of the cap, dozens of districts, many of which are experiencing enrollment gains, did not receive state funding increases commensurate with their growth. Conversely, certain districts with declining enrollment received extra state dollars—above and beyond their formula prescription—effectively funding “phantom students.” In short, both the cap and guarantee function outside of the formula and undermine its ability to drive money based on enrollment and wealth.

Second, the formula helps to level the playing field between districts of varying local wealth. In addition to allocating money based on enrollment, Ohio’s formula also takes into account the ability of districts to generate local revenue, which accounts for just over 40 percent of total K–12 education funding. The Ohio Department of Education puts it this way:

Historically, each district relied exclusively on its property taxes to support education, and most of the proceeds from these taxes went towards funding education. The problem with that arrangement was that since the property tax bases of different school districts varied widely, the educational services they provided also differed vastly. In response, Ohio intervened to provide money to school districts through the foundation formula. This foundation funding narrows the gaps in education funding between wealthy and poor school districts and increases funding equity.

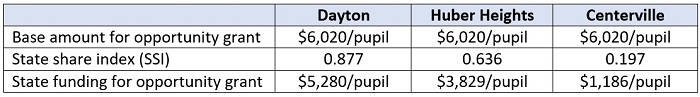

The key feature in Ohio’s current formula that works to meet these equity goals is the state share index (SSI). This mechanism adjusts funding amounts based on districts’ capacity to generate local money (i.e., their property values and resident income). The wealthier the district, the less state money it receives. The table below, using data for illustration from three Montgomery County school districts, shows how the index works in practice. Dayton is a poor, urban district, Huber Heights is a working-class suburb, and Centerville is a wealthy suburb. The calculations displayed below apply to their opportunity grant, the main funding stream within the overall formula. What’s evident from this table is that the SSI ensures that the two less affluent districts receive more dollars than Centerville, the wealthiest of the districts shown below.

Table 1: An illustration of the state share index in action (FY 2019)[2]

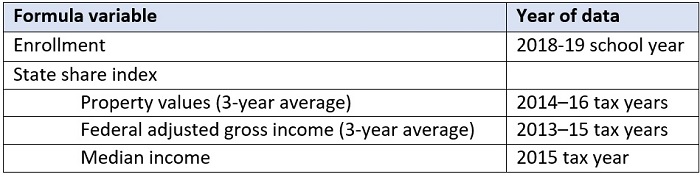

Third, the formula adjusts to changes in enrollment and wealth. District and charter school enrollments change from year-to-year, as do the wealth of districts. Districts, for instance, might get an influx of new students due to the closure of a local non-district school and demographic shifts could also affect yearly headcounts. They could also gain wealth in a short period of time through economic development, thus reducing their need for state aid; conversely, a district might see declines in wealth and need more help. Ohio’s formula takes into account these types of changes, basing funding on current-year enrollments of districts and charter schools. It also uses recent years of data about property values and resident incomes to compute state funding amounts. The table below displays the years of data that were used to calculate funding amounts in FY 2019. The slight lag in the property values and income data reflects a policy that calls for the SSI to be computed just once, in the first year of the two-year budget cycle.

Table 2: Data used to compute districts’ state funding amounts (FY 2019)

With a suspended formula, the state has ignored changes in district enrollment and wealth. Much like the cap and guarantee, the frozen formula has basically created a system of winners and losers, just at a statewide scale. Districts with rising enrollments or declining wealth “lose”—they are shortchanged relative to their present needs—while districts with falling enrollments or increasing wealth “win” because they receive more dollars than they should. In sum, suspending the formula yet again would further aggravate these problems. The state would be funding districts in FYs 2022–23 based on outdated enrollment and wealth data—hardly a fair or sensible method of divvying up state money.

* * *

Though it may never be perfect—and it’s certainly complicated—Ohio’s school funding formula is critical to ensuring a fair allocation of state funds. It works to direct state resources to the districts and charter schools that students actually attend. It also drives more dollars to districts that need state aid the most. Restarting a formula-based system, whether that is the current framework or another one that works to achieve these same ends, is something that Ohio’s next General Assembly must work towards.

[1] District “foundation aid,” which represents the bulk of state funding, was frozen but districts received additional dollars in FYs 2020-21 through the new student success and wellness fund. Total state funding amounts could also increase or decrease depending on the number of students exercising choice options. Charter school funding was not frozen; they’ve been paid based on current-year enrollments.

[2] Data were retrieved via Ohio Department of Education, District Payment Reports (FY 2019). Districts generally reach (or exceed) the full opportunity grant base amount through a state required 2 percent local property tax. The SSI ranges from 0.05 to 0.90, with higher values prescribing a higher state share of the base amount. Public charter schools effectively have an SSI of 1.0—they receive full base amounts—because they receive, with only a few minor exceptions, no local revenue. The SSI also applies to several other formula components, such as categorical funding for students with disabilities and English language learners.

Triennially, we Americans await the results of the international PISA tests with equal parts hope and dread, although who knows yet if we’ll get a bye for 2021. While we hope that this will finally be the year that our students have somehow whipped fill-in-the-blank country at last, we are also likely preparing ourselves to try and figure out, once again, why we can’t ever beat Finland. Is it the students, the education system of that country, or some combination of the two creating hard-to-beat, stellar outcomes?

The strong influence of parents on student achievement has been widely documented going back to Coleman in the mid-1960s. A number of research studies, plus Amy Chua’s widely-noted book, have added to the literature in recent years. A new report from two European economists tries to isolate the influence of tiger (and chestnut bear) moms on what they term human capital achievements, using PISA scores as evidence.

The researchers look at the achievement, via tests administered between 2003 and 2015, of more than 53,000 students who are second-generation immigrants from thirty-one PISA countries.[1] The idea is that, if some portion of the influence of the origin country’s education mojo was transferred via the parents, the scores of these immigrant students should more closely resemble those of the origin country—even if the kids no longer attend school there—than they resemble those of the new host country.

The main results bear out this hypothesis in a relationship described as “positive and tight.” That is, the score gaps that appear between native students in two different countries are largely preserved across the scores of second-generation immigrants. For instance, a Finnish immigrant student living and learning in another country will outperform, say, an American student by about the same amount as a native Finn still living and learning in Finland does, regardless of which country the immigrant student now calls home. These replicated test score patterns point to strong influences of home, with parents as the most likely conduit for transferring the influence.[2] To dig deeper, the analysts run a regression using individual math scores for those second-generation immigrants as the dependent variable and controlling for fixed effects of the school attended in the host country, for students’ demographic characteristics, language spoken at home, and family socioeconomic status. While the correlational pattern of cross-country test performance weakens upon regression, it is still positive and highly significant.

Attempts to pin down the exact mechanisms whereby parental influence is transmitted are not entirely successful. Observable socioeconomic characteristics of parents—such as education level and income—while easily isolated for analytic purposes, account for just 15 percent of the cross-country variation in test performance. It’s not clear what else is going on at home. Interestingly, the magnitude of the inferred unobservable characteristics, such as parenting style and cultural values, actually appears to be greater for parents who acquired very little education in their home country—and were therefore less exposed to the education system—implying influences that are far removed from formal education and seemingly more ineffable and innate.

But what to with these findings? Education reformers often look at school systems, buildings, and classrooms as the places to intervene to boost educational outcomes. While improving such inputs as teaching quality and curriculum is vital and valuable, research suggests these are likely not enough by themselves to improve human capital to the desired level. Parental influence is the key. The good news is that cultural values that prioritize education, perseverance, learning from failure, and the benefits of hard work are free and require no infrastructure to transmit and reinforce. The bad news is that it’s hard to come up with interventions in schools or the greater society that might promote such values where they are in short supply. Perhaps the best option is for schools to work to build new success mindsets and to boost such mindsets where they already exist. This new report seems to support this need.

SOURCE: Marta De Philippis and Frederico Rossi, “Parents, Schools and Human Capital Differences across Countries”, Journal of the European Economic Association (November, 2020).

[1] While the PISA data include a much larger overall sample of countries from which parents have emigrated, the researchers limit their analysis to origin countries with no fewer than one hundred emigrant parents represented so as to strengthen the comparison sample.

[2] It is not stated in the paper, which is focused on those immigrant students who achieve higher than native students in their host countries, but the implication is that effect works in reverse also.

Two groups likely to be disproportionately affected by Covid-19-related learning disruptions are students with disabilities and English language learners. A pair of new research briefs from the American Institutes for Research, part of a larger series of releases, provide insight about charter and district schools’ efforts to provide quality services to these at risk student groups. From May 20 through September 1, leaders from a nationally-representative group of school districts and charter management organizations responded to a survey that covered school closures, distance learning approaches and challenges, grading and graduation, staffing and human resources, and health, well-being, and safety.

The brief spotlighting English language learners (ELs) includes data from over 750 survey respondents from across the country.[1] Researchers were interested in two specific areas of support for ELs: The types of resources provided to students and families and the instructional expectations of teachers.

The good news is that a majority of respondents reported providing EL-specific distance learning resources, learning materials in Spanish (no other language provision was queried), and interpreters or liaisons for EL families. The less-good news is that district typology mattered greatly in these responses. Rural districts were far less likely to provide these supports than were their urban counterparts, and districts with lower percentages of ELs were also less likely to provide them than districts with high percentages of ELs. While this may seem like a logical outcome—more ELs means more supports for ELs—it could also mean tens of thousands of English language learners all over the United States were receiving little or no targeted educational support at this most critical time. It also seems to bolster what other evidence indicates: The robustness of a school’s educational program prior to the pandemic is a good indicator of how well it pivoted to a distance learning model.

The spotlight on students with disabilities (SWDs) illustrates almost across-the-board struggles for respondents. Closed-response survey items ask about schools’ ability to properly comply with various aspects of the federal IDEA law during a pandemic and to provide “typical” support services to SWDs and their families—think accommodations for completing in-class work, one-on-one supports, and the like.

Their reported difficulties are consistent with other research and anecdotal evidence from spring 2020. AIR survey responses indicated that nearly three-quarters found it more difficult to provide appropriate instructional accommodations for SWDs during school closures, while 82 percent said that providing hands-on instructional accommodations and services was more difficult. Even providing speech therapy proved more difficult for the majority of districts in a distance learning model. Rural districts reported more struggles than did their urban counterparts, but somewhat surprisingly, high-poverty districts often reported fewer struggles than did low-poverty districts. For example, nearly 55 percent of low-poverty districts reported they had more difficulty complying with certain aspects of the federal IDEA law, while just 47 percent of high-poverty districts reported the same. No conclusions are reached on why this might be, with discussion focusing more on the areas where high-poverty districts reported struggles.

There was one open-ended survey item which provides some encouraging news for the 2020–21 school year. The question asked “Has your district used any other strategies not mentioned in previous questions to support SWDs in a distance learning environment?” Innovations described by respondents included implementation of live telehealth therapy sessions, efforts to replicate the classroom environment in students’ homes, and an increased commitment of time and personnel for one-on-one virtual interaction with school staff and SWDs. Hopefully, these innovations have been replicated, boosted, and sustained.

SOURCES: Patricia Garcia-Arena and Stephanie D’Souza, “Spotlight on English Learners,” and Dia Jackson and Jill Bowdon, “Spotlight on Students With Disabilities,” American Institutes for Research (October 2020).

[1] The AIR briefs, including these two, all use the term “district” universally when speaking of survey respondents; it is assumed here that the term includes charter schools and charter management organizations, but the veracity of that assumption is unclear from these briefs or the survey’s technical supplement. CMOs were surveyed, but their responses are not, it appears, separated from those of traditional districts.

The Ohio House and Senate have each approved legislation, Senate Bill 89, which significantly changes the state’s EdChoice Scholarship program. The EdChoice Scholarship, Ohio’s largest voucher program, has been a topic of robust debate for the past year as lawmakers argued over what state report card measures should determine if a school is considered low-performing. Students at any school earning that designation qualify for a voucher.

“This past year has been full of uncertainty for Ohio families, and the changing requirements around EdChoice eligibility only made matters worse,” said Chad Aldis, Vice President for Ohio Policy and Advocacy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. “The legislature deserves credit for compromising and finding a long-term solution. Parents, private schools, and public schools deserve to know who is eligible and who isn’t for this important educational option.”

The changes enacted will reduce the reliance on the state report card for determining eligibility and shrink the number of public schools whose students would be eligible for the performance-based EdChoice Scholarship from more than 1200 to just under 500. At the same time, the legislation expands eligibility for the income-based EdChoice program by increasing the amount of money a family can make to qualify from 200 percent to 250 percent of the federal poverty level (about $65,000 for a family of four).

“In the long term, these changes will be very positive for Ohio families and schools,” Aldis added. “These last eight months have reminded us that education isn’t one size fits all. Families need options. The EdChoice program is well positioned going forward to provide opportunities to many more Ohio students—especially the most disadvantaged—to find a school that works for them.”