Ohio’s blind spot: Young people’s workforce outcomes

Ohio, like many other states, has made college and career readiness a major priority.

Ohio, like many other states, has made college and career readiness a major priority.

Ohio, like many other states, has made college and career readiness a major priority. The state’s strategic plan for education, for instance, aims to increase the number of young people who enroll in college or technical schools, participate in apprenticeships, enlist in the military, or obtain gainful employment. Achieving this goal will require strong policies and practices, along with the ability to track these post-secondary outcomes to gauge progress and pinpoint areas needing attention.

On the higher education side, Ohio already reports reliable data on college going and degree completion. The state does this through linkages to the National Student Clearinghouse, a nonprofit organization that collects data from almost all U.S. colleges and universities. These results appear on district and school report cards. From this same data source, we can also see statewide trends in college enrollment and completion, the latter of which are on the rise.

But not everyone pursues post-secondary education, at least right away. The most recent data indicate that 44 percent of the class of 2016 did not enroll in college shortly after high school. So what happens to those young people? Are they on pathways to rewarding careers?

Information about these workforce questions is far murkier. The state’s Career-Technical Planning District (CTPD) report card contains statistics about career-and-technical education (CTE) students’ outcomes in the areas of apprenticeships, military enlistment, employment, and higher education. Sounds promising, right? But there are four problems with Ohio’s current approach to reporting workforce outcomes.

Problem 1: Data are limited to small segment of graduates

The CTPD report card reflects only the outcomes of CTE students, or more specifically “concentrators,” who take at least two career-technical courses in a career field. Across Ohio’s ninety-one CTPDs, 29,675 students were reported as concentrators in 2018–19, thus representing roughly 20 percent of Ohio’s graduating class. Since the state includes no data about military enlistment, employment, or apprenticeships on traditional district or charter school report cards, we have no information about the workforce outcomes of the large majority of Ohio students.

Problem 2: Relies on surveys, with no verification checks

The CTPD data are collected via surveys of graduated CTE students, and no checks are conducted to verify that the results are reported accurately. ODE describes the process this way, with a caution about reliability in bold (my emphasis):

Districts begin following up their students in the fall after they leave.... In the survey, they ask students to tell report [sic] what they did professionally after leaving school, including asking if they are in an apprenticeship, enrolled in post-secondary education, employed or if they joined the military. It is important to understand that for this element, all data are self-reported by the former students. There is no confirmation check performed by ODE or by the districts.

The warning is worth heeding, as there are reasons to doubt the accuracy of these survey data. Some respondents might feel compelled to say they are in the workforce or college, when they really aren’t—a type of social desirability bias. Some of the terms could also be ambiguous: What exactly counts as an “apprenticeship” or “joining the military” (an intention to join, or actual enlistment)? When in doubt, respondents might affirm that they’re doing these things, something of an acquiescence bias.

Due perhaps to these issues, some questionable results emerge. For instance, an average of 4.2 percent of CTE students say they joined the military. While it’s possible that career-technical students are more inclined to enlist, this rate far exceeds the roughly 1 percent of American eighteen- to nineteen-year-olds that the federal government reports as enlisted. Moreover, a few CTPD’s post-secondary college enrollment data look suspect, as their rates significantly exceed those of the traditional school district serving students in the same area.

Problem 3: The employment data are coarse

All that is reported on the CTPD report card is whether a CTE student is employed, or not. It’s a straight up employment rate, with no other information given about the type of employment, career field, or salaries and wages. For example, the Lorain CTPD report card states that 58 percent of students reported employment. Although that statistic is a starting point, it tells us nothing about the quality of the jobs students obtain. What proportion are working full-time compared to part-time? How many are in minimum wage jobs versus entry or mid-level jobs in good-paying career fields? Unfortunately, Ohio doesn’t present anything finer that would help us better understand students’ transitions into the labor market.

Problem 4: Duplication across categories

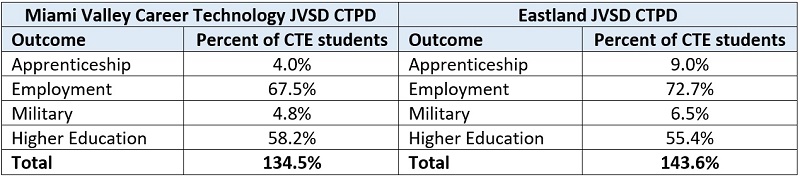

Ohio’s approach to presenting workforce outcomes on the CTPD report cards results in a significant duplication of students. Consider Table 1 below, which displays results for two of Ohio’s larger CTPDs, selected for illustration purposes. It’s clear from the “total” rows that students fall into multiple outcomes, as the percentages exceed 100 percent. This is likely the result of young people who work and attend college concurrently reporting participation in both (those in an apprenticeship or the military may also consider themselves employed).

Table 1: Post-secondary outcomes for two selected CTPDs, 2018–19

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: The Miami Valley CTPD oversees CTE in twenty-seven districts in Southwest Ohio; the number of CTE students in its graduating cohort was 953 in 2018–19. The Eastland CTPD oversees CTE in sixteen districts in Central Ohio; the number of CTE students in its graduating cohort was 897 in 2018–19.

Duplicate reporting is not always a bad idea, but in this case, it clouds our picture of students who do not enter post-secondary education. Because we don’t know what fraction of the employment rate represents students who work while in college, we cannot determine the employment rate of non-college-goers.

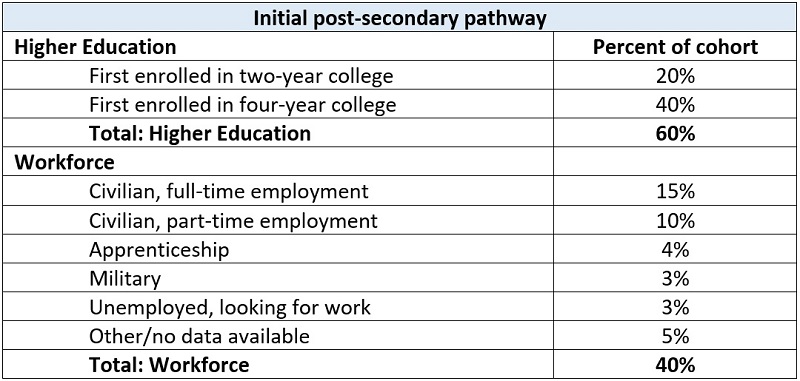

A clearer presentation might split the higher education and workforce data. Table 2 presents a rough sketch of what the reporting could look like. The top panel covers students who enroll full-time in college, while the bottom focuses on those who enter the workforce after high school. Because college students are excluded from the labor market data, this approach offers a sharper picture of the workforce pathways of non-college-goers. This framework could also serve as a basis for presenting more detailed information. For example, the civilian, full-time employment category could be divided by salary (e.g., $30,000 and below, $30,000 to $60,000, etc.) to offer a view of job quality.

Table 2: Proposed framework for reporting higher education and workforce outcomes separately

* * *

In sum, Ohio needs to make advancements in its data collection and reporting methods when it comes to workforce outcomes. Fortunately, the state is currently working to link information systems that should yield more trustworthy data about what students do after high school. That effort received a boost when the Ohio Department of Education recently announced a $3.25 million federal grant aimed in part at connecting K–12 and workforce data. Assembling reliable data, however, is only half the battle. Ohio also needs to consider clear, transparent ways of presenting the information for students attending all schools, whether career-technical or general education.

Ensuring that each student succeeds in college and career remains a central aim of Ohio. Curing our blind spots about workforce outcomes would go a long way in gauging progress toward that admirable goal.

Last week, I wrote a piece about Pathways, a statewide program in Delaware that offers students the opportunity to complete a program of study aligned with an in-demand career before they graduate.

Although it’s too soon to know its long-term impact, the nuts and bolts of the program are laudable. It expands educational options for students, provides work-based learning and dual enrollment opportunities, and improves collaboration between businesses and schools. It seems like a no-brainer to recommend that Ohio follow in Delaware’s footsteps and create a Pathways program of its own.

But doing so would be far more complicated than copy and pasting legislation. For starters, there’s a significant size mismatch between the two states. Delaware has just 141,000 students enrolled in preschool through twelfth grade in all its public schools. Ohio, meanwhile, has approximately 125,000 students enrolled in every single grade and over 1.6 million overall. There are 610 public school districts in Ohio compared to nineteen in Delaware. And Ohio’s largest traditional public district—Columbus City Schools—serves just over 50,000 students, which is more than a third of Delaware’s entire K–12 population.

There are also some more abstract differences. According to a recent report from R Street, Delaware has a long history of positive public-private partnerships. Ohio has been trying to better connect the public and private sectors, but there has been considerable pushback to such efforts in the K–12 arena. The report also notes that Delaware’s state culture—known as “the Delaware way”—makes hammering out cross-sector and across the aisle deals smoother. Considering the contentious education debates that have lately dominated headlines, the same probably can’t be said for Ohio.

Nevertheless, establishing a program like Pathways in Ohio could positively impact the lives of thousands of students, provide local businesses with well-prepared workers, and boost that state’s economy. It’s definitely worth considering, and there are three key lessons to learn from Delaware:

Lesson one: Secure government and private funding

In his recent report on Pathways, Larry Nagengast noted that the use of both government and private funding streams was “essential” to the program’s growth. For example, the state department of education’s Office of Career and Technical Education distributed $2.8 million in grants to districts and charter schools to expand their pathways, and Bloomberg Philanthropies and JPMorgan Chase provided $3.5 million and $2 million, respectively, to support the program and its work-based learning components. Obviously, these weren’t the only funding amounts or sources needed to make Pathways a success. But they reflect the importance of having significant and roughly equivalent levels of investment from government, business, and philanthropy. Without robust and sustainable funding, the program won’t work or last. To make Pathways work, Ohio leaders would need to propose significant state investment during the next budget cycle and convince philanthropic and business organizations to pledge their support. Furthermore, because of size differences, investors should expect Ohio’s program to be considerably more expensive than Delaware’s.

Lesson two: Focus on regional programs instead of a statewide initiative

Because of the significant size difference between Delaware and Ohio, leaders in the Buckeye State would be wise to focus on launching multiple regional initiatives that operate under a state-created framework rather than a single, massive program run directly by the state (as is the case in Delaware). One way to do this would be to work through Ohio’s six College Tech Prep Regional Centers. These entities are jointly managed by the Ohio Department of Higher Education and the Ohio Department of Education’s Office of Career-Technical Education. They serve as liaisons between community colleges, universities, and the state’s ninety-three career-technical planning districts (CTPDs), which oversee the administration of all of the state’s existing CTE programs. Since the centers are regionally based, they are far better equipped than state leaders to identify and address a wide variety of potential problems, such as transportation issues in rural areas. They are also ideally situated to facilitate collaboration between secondary and postsecondary education providers as well as traditional and technical providers.

Lesson three: Identify intermediaries to facilitate collaboration between schools and businesses

Nagengast pointed out that making work-based learning—the defining characteristic of the program—effective on such a large scale required “the involvement of an experienced partner” who could serve as an intermediary between K–12 and the business community. In Delaware, that partner is Delaware Technical Community College. In Ohio, community colleges could play a similar role. There are several of them already doing such work. But it would take some significant legwork to connect all of the state’s community colleges with schools and businesses.

***

Without a doubt, getting a Pathways program off the ground and implementing it effectively would be a heavier lift in Ohio than it has been in Delaware. But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible. In fact, we’re more than halfway there. Delaware’s Pathways program is part of a Jobs for the Future network called Pathways to Prosperity, which includes similar programs in fifteen other states. One of those states is Ohio, though its involvement is only at a regional level—Central Ohio to be specific. Like Delaware, Ohio has an attainment goal that’s looming large, and a governor who is committed to expanding CTE and workforce opportunities. And Ohio already offers students some of the same opportunities that are a hallmark of Delaware’s Pathways program: dual enrollment, which is available through College Credit Plus and articulated credit options like Career-Technical Credit Transfer; and work-based learning, for which Ohio created a decent foundation through its work with New Skills for Youth.

But that’s not all. In the recent budget, lawmakers passed several policies that indicate an interest in funding programs like Pathways. The Ohio Industry Sector Partnership Grant, for instance, funds collaboration between businesses, education and training providers, and community leaders interested in improving regional workforces. A total of $2.5 million is available per year for two types of grants: spark grants, which fund emerging partnerships, and accelerant grants, which are intended to stimulate the work of existing partnerships. And the Innovative Workforce Incentive Program helps schools establish credentialing programs and incentivizes student attainment by offering schools $1,250 for each qualifying credential earned by students. These aren’t huge pots of funds, and a Pathways-like program would certainly need more. But they’re a good start.

Business Advisory Councils, or BACs, could also play an important role in connecting schools with local employers. State law requires every school district and education service center to have a BAC whose role is to advise districts on changes in the economy and job market, and to aid and support them by offering suggestions on how to develop a working relationship with businesses and labor organizations. BACs are permitted to conduct a broad range of activities, including organizing internships, cooperative training, work-based learning, and employment opportunities for students—all of which are key parts of Delaware’s Pathways program. Having BACs join forces with College Tech Prep Regional Centers could connect the business and education sectors and ensure that pathways are aligned to the region’s most in-demand careers and local employer needs.

The upshot? Ohio already has a solid foundation of policies, funding, and partnerships in place to make a new initiative like Pathways work for thousands of Buckeye students. All we really need to do is tie it all together into one coherent, streamlined initiative and then expand it. Which, admittedly, is easier said than done. But if lawmakers and state leaders are serious about reaching Ohio’s attainment goal and improving workforce outcomes, taking a close look at Delaware’s Pathways program would be a good place to start.

It’s no secret that tough accountability measures are out-of-fashion in education circles these days. After much political debate, Ohio, for instance, has backpedaled on the implementation of stricter teacher evaluation, suspended accountability consequences during a recent period of “safe harbor,” and is actively debating whether to repeal the state’s district-intervention model. Riding the anti-accountability wave, education groups have been pushing lawmakers to dump Ohio’s A–F school rating system, which they’ve decried as “destructive” and “punitive.” Instead, they’ve advocated for the use of milquetoast descriptors such as “not met” and “very limited progress,” or numerical systems like 0–4.

All these proposals would avoid the use of an “F”—a letter associated with “failure”—to identify low-performing schools. It’s not, of course, surprising to see organizations representing the adults in the system favoring gentler, euphemistic terms that can help insulate schools from public criticism. But at the same time, we should ask whether the dreaded “F” is a necessary tool that can help protect students from the harms of truly deficient schools.

This post examines the academic data of schools assigned an overall grade of F under the state’s accountability system. The numbers are small: Just 8 percent, or 275 schools (204 district and 71 charter) received such a rating in 2018–19.[1] But their results suggest a continuing need for a red flag—an alarm bell—that warns parents, communities, and governing authorities that students in these schools are far behind, with little chance of catching up. Let’s dig in.

Student proficiency

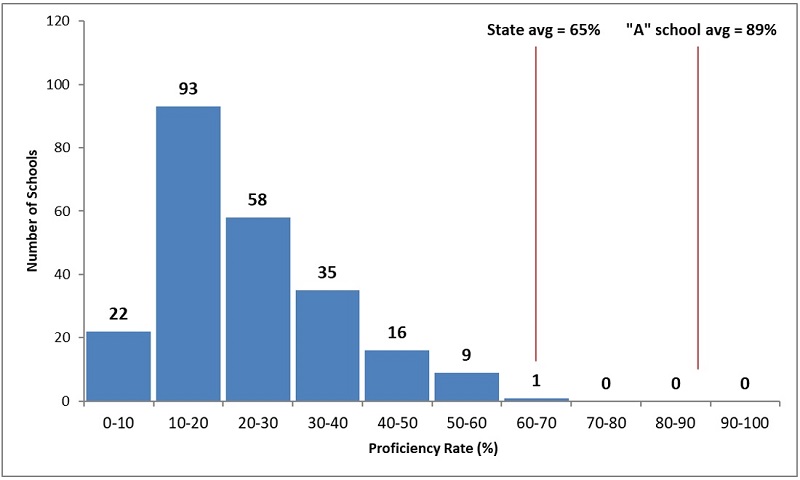

First, we look at proficiency rates, or the percentage of students reaching “proficient” or higher on state exams. Figure 1 displays the number of F-rated schools within ten equal intervals ranging from 0 to 100 percent proficiency. The bar at the far left of the chart, for instance, shows that twenty-two F-rated schools had proficiency rates between 0 and 10 percent last year. Overall, we see that a large majority of these schools post very low proficiency rates: 173 of 234 schools have proficiency rates below 30 percent. The average proficiency rate of F-rated schools is just 25 percent, less than half the statewide average and far behind the proficiency rates of A-rated schools. A small number of outliers register rates closer to the statewide average, but on the whole, the vast majority of students attending F-rated schools fall short of state academic standards in core subjects such as English, math, and science.

Figure 1: Proficiency rates of overall F-rated schools, 2018–19

Source for figures 1–3: Ohio Department of Education. Note: The average proficiency rate across the F-rated schools is 25.1 percent.

Student growth

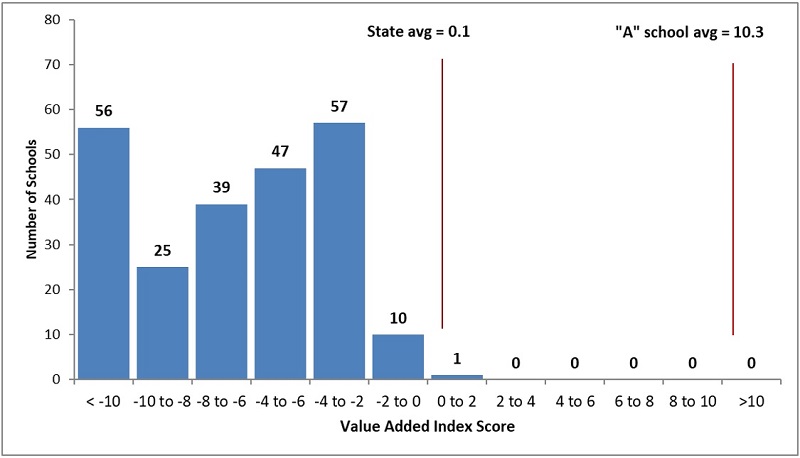

Despite low proficiency rates, the schools shown above might be helping students make significant academic progress that could eventually lead them to achieve proficiency on state tests. Figure 2 examines that possibility. It shows F-rated schools and their value-added index scores, a measure of statistical certainty that a school produces learning gains or losses that are different from zero (zero indicating that the average student maintains her position in the achievement distribution).[2] A score of -2.0 or below is usually interpreted to mean that there is significant evidence of learning losses, with lower values—e.g., -5.0—indicating stronger certainty that the average student lost ground. What we see in the figure below is that almost all of the state’s F-rated schools—224 out of 235—register value-added index scores below -2.0. This indicates that not only are students struggling to meet proficiency targets, but they are also falling further behind their peers.

Figure 2: Value-added index scores of overall F-rated schools, 2018–19

Note: At a school-level, value-added index scores range from -47.8 to 35.0. The average value-added index score for F-rated schools is -9.7.

It’s critical to recognize that poor value-added results cannot be simply blamed on demographics. Because these growth measures control for students’ prior test scores, high-poverty schools can and do perform well on this measure. Quite a few of them regularly receive A’s and B’s on the value-added measure. Students struggling to meet proficiency targets need schools that accelerate learning. Sadly, these data indicate that F-rated schools are not only failing to provide the academic growth required to achieve proficiency before exiting high school, but allow students to fall even farther behind.

College readiness

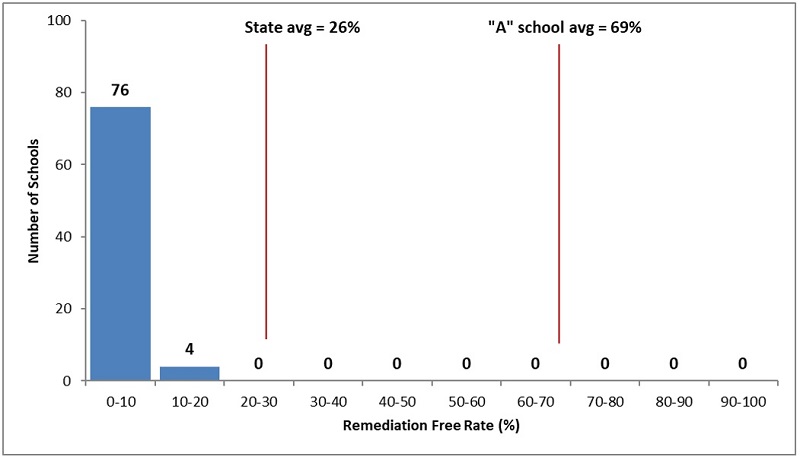

Speaking of high schools, a final data point worth examining is the percentage of students meeting the state’s college remediation-free standards on the ACT or SAT exams. Figure 3 shows the data among students attending F-rated schools. In seventy-six out of eighty F-rated high schools, less than 10 percent of students achieve a remediation-free score. The average remediation-free rate among these schools is a miniscule 3.8 percent, well behind the state average of 26 percent and a far cry from the 69 percent of students attending A-rated schools. Simply put, a depressingly small fraction of students who attended these high schools are prepared to handle the rigors of post-secondary education.

Figure 3: Percent scoring remediation-free on the ACT or SAT of overall F-rated schools, 2018–19

Note: The average remediation-free rate for F-rated schools is 3.8 percent.

* * *

All students deserve a quality K–12 education that puts them on a solid pathway to college and career. Unfortunately, the abysmal outcomes of some Ohio schools indicate a lack of success in achieving that goal. While it may be uncomfortable, the state has an obligation to identify such schools, and the overall “F” rating is the clearest possible signal of distress. The red flag serves a couple important purposes that help to protect families and students:

Sugarcoating failure through nebulous descriptors or opaque numerical systems is unlikely to spur organizational change or alert parents about the risks of attending low-quality schools. Although an “F” rating may feel destructive to some, it can actually shield students from the long-term harms of being unable to read, write, and do math proficiently. As the debate continues around report cards, Ohio policymakers need to remember the importance of clear, transparent ratings.

[1] The analyses below exclude about forty F-rated early-elementary schools that lack these report-card data.

[2] The index scores—the estimated value-added gain or loss divided by the standard error—are used to determine the value-added ratings. Though also influenced by school enrollment size, larger index scores suggest more sizeable learning gains or losses.

In December, a workgroup established by the State Board of Education released a number of policy recommendations related to dropout-recovery charter schools. Representing a modest but not insignificant portion of Ohio’s charter sector, these schools enroll about 15,000 students, most of whom have previously dropped out or are at risk of doing so. The policies governing dropout-recovery schools have been much debated over the years—particularly their softer alternative report card—and this report follows on the heels of a 2017 review of state policy.

In general, the workgroup’s report offers recommendations that would relax accountability for dropout-recovery schools, most notably in the area of report cards. Though disappointing, that’s not surprising; save for two seats held by state board members, the entire work group comprised representatives from dropout-recovery schools. Regrettably, they seem to have used their overwhelming influence to push ideas that would make their lives a bit more comfortable but not necessarily support students’ academic needs.

In a pointed response to the workgroup report, state superintendent Paolo DeMaria rightly expressed concern. He wrote:

As might be expected of a process that was somewhat one-sided, the recommendations contained in the Work Group report favor loosening regulations of schools operating dropout prevention and recovery programs.... Consequently, the Work Group process reflects members of a regulated educational sector given carte blanche to design their own regulations, resulting in a decidedly one-sided report.

Although the workgroup claims that “high standards must be maintained for at-risk students,” its proposals would significantly lower the standards for dropout-recovery schools. Specifically, their suggestions include:

These recommendations are unsettling for several reasons.

First, excluding certain students from accountability measures undermines the basic principle that all students can learn, and it contradicts a central tenant of accountability: that schools should be incentivized to pay attention to—not ignore—students struggling to achieve state goals. Ohio already relaxes report card standards on the test-passage and graduation components, and excluding students would further erode accountability for their academic outcomes.

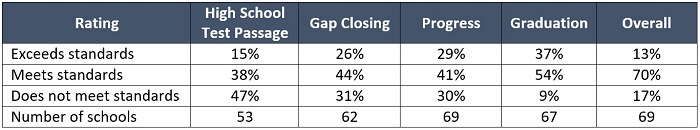

Second, the proposal to reduce the weight on the achievement-based component could be seen as an effort to inflate overall ratings. On the four current components on the dropout-recovery report card, the High School Test Passage component is the most stringent: 15 percent of schools are rated “exceeds standards”; 38 percent receive “meets standards”; and 47 percent get “does not meet standards.” As the table below shows, the ratings on the other components are generally higher. Consequently, the overall ratings of a number of schools would rise even though performance hasn’t actually improved.

Table 1: Distribution of overall and component ratings for dropout-recovery schools, 2018–19

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: The weights used to calculate the Overall rating are as follows: high school test passage, 20 percent; gap closing, 20 percent; progress, 30 percent; and graduation, 30 percent. For more information about the dropout-recovery report card, see here.

Third, the replacement of an objective, assessment-based progress component with a course-credit driven measure would make school quality harder to evaluate. The growth rating is especially critical when schools serve students who are behind, and its removal would leave communities and authorizers less able to gauge academic performance. In contrast, relying on credits is unlikely to yield credible information about student learning. Unless the state imposes very strict rules around awarding course credit, the measure could be easily gamed by low-quality providers using dubious forms of credit recovery.

Fourth, akin to course credits, the two new dimensions—the life-readiness and culture components—would also be open to gaming and abuse. Without clear definitions—and the workgroup doesn’t suggest any—activities such as “service learning” or a “community-business partnership” could mean almost anything. These components also shift the focus from key measures of achievement and growth, potentially masking student outcomes in favor of check-box activities.

***

In a sense, the dropout-recovery workgroup engaged in what one might term “regulatory capture,” whereby the ones being regulated attempt to write the rules. But policymakers also need to realize that the potential for mischief is not unique to dropout-recovery schools. In the broader debate over report cards, for instance, school associations and teachers unions have promoted policies that would weaken the accountability systems applying to the schools in which they work. Among these policies are the elimination of clear ratings, the use of opaque data dashboards, a reliance on input-based measures that could be manipulated to boost ratings, and the use of check-box indicators of participation in certain programs or activities.

School employee groups should certainly have their say in the policymaking process, as they are uniquely positioned to see problems and offer solutions. But we must be mindful that they—like those in the dropout-recovery workgroup—can use their privileged position in policy discussions to further interests that aren’t necessarily in the benefit of the broader public. Whether making policy for a broad swath of Ohio schools or a small segment of them, policymakers need to listen to a wide range of views.

[1] For the dropout-recovery report card, Ohio uses an alternative assessment of student growth based on the NWEA MAP test.

Mentoring programs connect young people with caring adults who can offer support, guidance, and even tutoring. Research indicates that such programs can be valuable for students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Given these benefits, it makes sense that state leaders would be interested in supporting mentorship programs. In a recent report that’s part of a broader series of case studies on civil society from R Street, Amy Cummings takes a closer look at Ohio’s Community Connectors, a program that awarded grants to community partnerships to provide mentoring to students.

Community Connectors was jointly established in 2014 by former Governor John Kasich and the Ohio Department of Education. The program was not directly aimed at improving test scores or graduation rates. Instead, it was viewed as an opportunity to encourage community organizations to establish mentoring programs that could improve the overall education, health, and workforce readiness of students. To be eligible for funding, partnerships had to consist of at least three different entities: a business, a faith-based organization, and a school district. Most partnerships included several additional groups, such as parent networks and community-based organizations.

Grants were awarded to partnerships that served students in grades five through twelve who were enrolled in low-performing, high-poverty schools. Between July 2015 and July 2018, Community Connectors awarded more than $36 million to 172 unique partnerships. Approximately 14,000 students were served by 5,300 mentors in forty-five of Ohio’s eighty-eight counties. In total, participants received 67,000 hours of one-on-one mentoring and 91,000 hours of mentoring via group activities. The program ended in 2019, after four rounds of grants.

Although hard evidence on academic impacts is lacking, there is anecdotal evidence that the grants spurred community partnerships. Cummings, for instance, profiles a mentoring program housed by Big Brothers Big Sisters of West Central Ohio, the result of a partnership between the Hardin County Common Pleas Court’s Juvenile Division, the Hardin County Sheriff, Our Savior’s Lutheran Church, US Bank, and three school districts—Hardin Community Schools, Lima City Schools, and Perry Local Schools. The state awarded the partnership $86,000 to mentor at-risk middle and high school students. The program targeted students with a history of truancy, chronic inappropriate behavior, substance abuse, and academic failure. Over 97 percent of these students lived in poverty, and more than half of them reported a family history of alcohol abuse and/or drug abuse. Based on a survey given to teachers of participating students, the program succeeded in impacting school-related factors: 63 percent reported seeing an improvement in class participation, and 51 percent reported improvements in academic performance.

The report concludes with several lessons learned. Given that it’s part of a series on civil society, many are related to the role of government in encouraging engagement from community-based organizations. But some of them are also worth applying to education policy. For example, when supporting innovative programs, it’s important to consider whether they are sustainable if government funding ceases. It is also critical that success is measured based on the underlying goals of a program. In the case of Community Connectors, civil engagement and community partnerships were the goal. The program certainly succeeded in that regard. And although it lasted only a short while, its impacts could be long lasting.

SOURCE: Amy Cummings, “Ohio's Community Connectors Program,” R Street (November 2019).