Four ways that Ohio lawmakers can bolster the early literacy push

Governor DeWine recently unveiled a bold plan to significantly improve early literacy in Ohio.

Governor DeWine recently unveiled a bold plan to significantly improve early literacy in Ohio.

Governor DeWine recently unveiled a bold plan to significantly improve early literacy in Ohio. His strategy centers on requiring schools to use curriculum and materials that are aligned with the science of reading—instruction based on the well-established five pillars of literacy: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. Phonics, which teaches children to recognize the relationship between sounds and letters and then use that knowledge to decode words, is particularly important for foundational reading. To support rigorous implementation of evidence-based practices, the governor has also recommended $174 million in additional state spending on literacy initiatives.

The governor deserves lots of kudos for tackling early literacy with the urgency it deserves, especially amidst data indicating that thousands of Ohio students are struggling to read fluently. But plans can always be sharpened and strengthened, and we wish to offer four ways that House and Senate lawmakers could improve upon the foundation laid by the governor. Consider the following:

1. Shore up the provisions around high-quality instructional materials

Curriculum reform isn’t typically exciting, but in places where it’s been implemented effectively, it’s had positive impacts. That includes Mississippi, where state leaders have focused on aligning instruction, including curriculum, and teacher professional development with the science of reading, and have seen greatly improved student outcomes as a result. DeWine’s plan follows in Mississippi’s footsteps (along with other states) by requiring schools to use high-quality curriculum aligned with the science of reading, while providing funding for high-quality instructional materials. But there are two places where the governor’s plan could use some shoring up.

First, as a matter of full transparency, legislators should require districts to post and annually update their websites with information about which core reading curriculum and literacy intervention programs are being used at each of their schools. As is the case in Colorado, this would ensure that schools are being transparent with parents and taxpayers about their efforts to meet state requirements around high-quality curricula.

Second, DeWine’s proposal calls for a statewide survey to gather information on the core reading curriculum, materials, and literacy intervention programs currently being used by public schools. That’s a critical step; state leaders need to know what schools are using. But to ensure accuracy, the state should add language that requires schools to be specific in their answers. The devil is often in the details. That means including not only the title of the curriculum or resource, but also the publisher and year of publication. These are important details, as curricula and textbooks change and earlier versions may not be as well-aligned as their more recent counterparts.

2. Scrap the waiver language

DeWine’s proposal wisely prohibits schools from using the three-cueing approach, which deemphasizes phonics and instead encourages students to make predictions and use context clues (i.e., guess) to identify words. But the governor’s proposal also gives schools an out. They can apply to ODE for a waiver “on an individual student basis” to use curriculum and materials that embrace ineffective three-cueing. ODE must consider the district or school’s performance on state report cards, including the early literacy component, before granting a waiver.

Unfortunately, this provision isn’t what’s best for students. Research overwhelmingly indicates that three-cueing doesn’t work. Using pictures and context clues to guess words isn’t reading, and sooner or later, those “skills” will cease to serve students well. Furthermore, adding a waiver for individual students overlooks that most curriculum are used school-wide, grade-wide, or within specific classrooms. When students need individualized attention and specialized materials, it’s typically because they’re struggling—in which case, methods like three-cueing should be the last thing that teachers use.

3. Consider how to respond to non-compliance

While the overwhelming majority of schools would likely follow a science of reading requirement—and many, in fact, already use this model—it’s also possible that some will drag their heels. To address such situations, state leaders should add non-compliance provisions. Possible avenues include withholding a portion of state funding (something that Arkansas does) and/or issuing a corrective action plan. Schools that continue to use misaligned or low-quality curriculum should be held responsible for the negative impacts that these decisions can have on students, and the state should ensure that steps are quickly taken to shift gears.

4. Ensure teacher preparation programs are following the science

The governor’s proposal focuses on overhauling literacy instruction through professional development and curricula reforms that impact current teachers and students, which should be celebrated. But the state should also ensure that its next generation of teachers is properly trained in the science of reading. Otherwise, elementary schools will need to retrain incoming teachers all over again (at enormous cost to students and to budgets). Lawmakers could ensure that teacher candidates receive rigorous training by creating a new review process that requires elementary preparation programs to provide evidence of alignment with the science of reading. Program approval from the state would then hinge on such reviews.

***

Policymakers have a moral obligation to ensure that schools are doing what’s best for kids—especially in regard to reading, the cornerstone of academic and lifelong success. Governor DeWine’s early literacy proposal is both well-timed and backed by research indicating that literacy instruction based on the science of reading gives students the best opportunities to becoming fluent readers. With a few adjustments—and a steadfast commitment to see all of this through—Ohio will be poised to make real progress in literacy.

Shannon Holston serves as NCTQ’s Chief of Policy and Programs.

School choice and parental empowerment are among the hottest topics in education these days. Here in Ohio, state lawmakers are actively discussing proposals that would strengthen private school choice and public charter schools. One topic that doesn’t get as much attention is interdistrict open enrollment, one of Ohio’s oldest and most popular choice programs. As we’ll see in this piece, lawmakers still have room to improve this program by making it accessible to more students.

Under this policy, students are allowed to attend public schools in a neighboring district, tuition-free. This opens up significant possibilities: Students can attend schools that offer special academic or extracurricular programs that aren’t available in their home district. It can allow them to attend a school with close companions or one that is closer to their home. For students from less advantaged communities, open enrollment can increase access to higher-quality schools located in their vicinity—schools that tend to be more racially and socioeconomically diverse, as well.

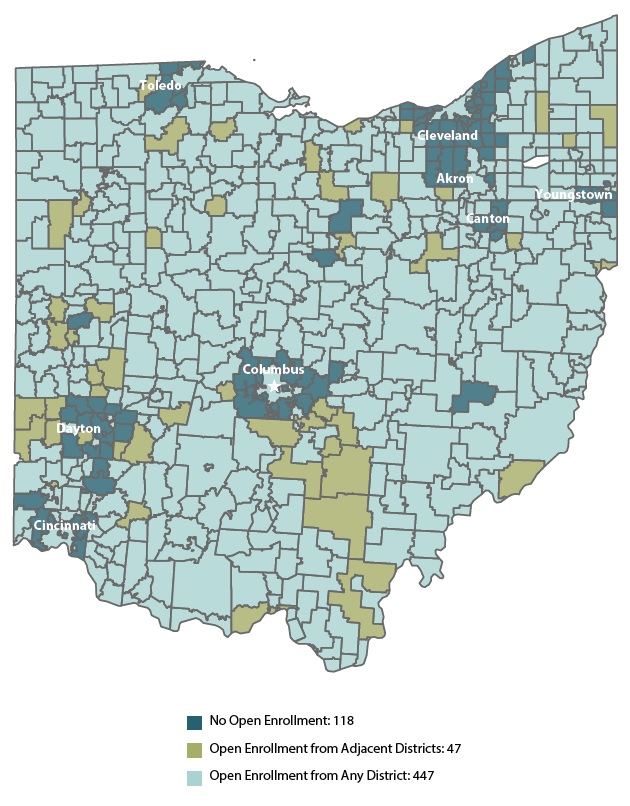

To their credit, a large majority of Ohio districts allow non-resident students to open-enroll, and approximately 80,000 students avail themselves of this opportunity. But—as permitted under Ohio’s voluntary participation policy—about one in six districts forbid open enrollment. They choose to close their doors to outsiders, allowing only children who reside in the district to attend their schools. As the figure here shows, refusing districts (shaded in dark blue) are located almost exclusively around Ohio’s largest cities. This map is based on 2018 district participation in open enrollment, but the pattern continues today. These suburban districts are overwhelmingly White and affluent, while the center-city districts are overwhelmingly Black and poor. Some might say that this is what systemic racism looks like; at the least, it’s a form of “educational redlining.”

We at Fordham and others have argued that state law should require all districts to participate in open enrollment. This would unlock options for more Ohio students, especially children who live in urban areas and lack district-run options other than those provided by their home district. It would also allow more suburban students to transfer from one district to another, without having to pick up and move.

Yet one commonly heard objection to such a requirement is that districts don’t have the physical space to serve more students. That’s a fair concern, and legislators would be smart to include a capacity waiver provision in a switch to mandatory participation.

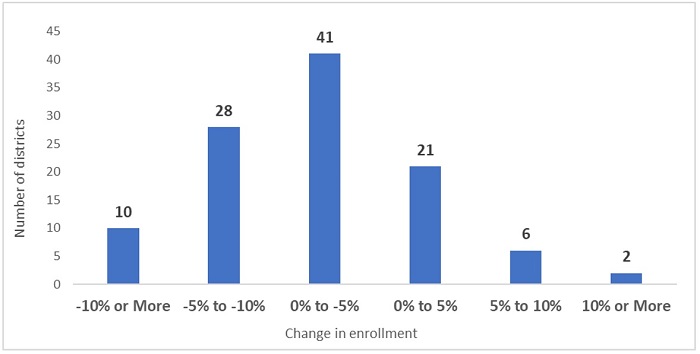

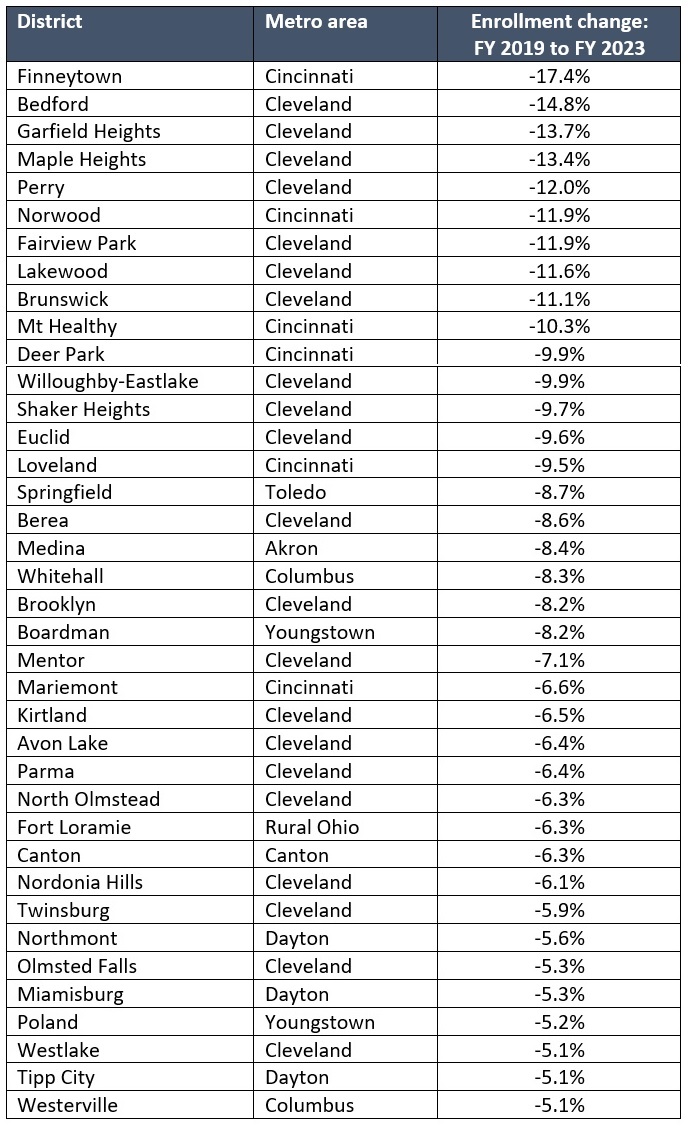

But it’s also important to understand that this objection doesn’t apply in most cases. Consider the data shown in Figure 1. Of the 108 districts that aren’t accepting open enrollees this year, 79 of them have experienced enrollment losses from 2018–19 to 2022–23. In 38 of these districts, the declines are fairly steep (more than 5 percent). As Table 1 indicates, most of these rapidly shrinking districts are located in Northeast Ohio, a region that has experienced flat to declining general population trends. In the Cleveland area, for instance, Bedford, Garfield Heights, and Maple Heights school districts have all experienced enrollment losses of more than 13 percent since 2018–19. Surely, districts such as these have room in the inn.

Figure 1: Change in enrollment among non-participating districts from 2018–19 to 2022–23

Table 1: Non-participating districts with declines of more than 5 percent from 2018–19 to 2022–23

* * *

Districts with declining enrollments have no excuse for refusing students who want to attend their schools. Financial implications shouldn’t be a deal-breaker, either, as the state provides per-pupil funding that should cover the incremental cost of educating additional students. While the district may have increased expenses for items such as textbooks and supplies for open enrollees, it won’t need to spend significantly more on facilities or teacher salaries when they fill empty seats. Those types of fixed costs are already paid for. In fact, operating closer to capacity would not only benefit students, but could also achieve efficiencies that allow districts to stay off the local levy ballot.

Public schools should be “open to all.” By denying access based on a student’s zip code and requiring parents to purchase housing in their districts to attend, non-participating districts continue to defy that principle. State lawmakers should finally step in to address the nonsensical refusal of certain districts to serve Ohio students.

The wage difference between college and high school graduates, or the “college wage premium,” grew during the pandemic. On average, recent college graduates earn $52,000 per year compared to the $30,000 earned by those with only a high school diploma. Nevertheless, an increasing number of teenagers are deciding to forego college despite the documented financial benefits. Nationally representative surveys of high school students conducted over the last few years indicate that the cost of higher education is the primary reason why.

It’s hard to blame teenagers for wanting to avoid the crushing debt that’s dominating headlines and impacting the lives of older generations. It’s also important to recognize that skipping a traditional four-year college isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Opting for a career and technical education (CTE) program offers plenty of benefits, including boosted income and a chance to develop valuable soft skills. The industry-recognized credentials associated with career pathways have proven to be valuable to both students and employers. Work-based learning opportunities like those in Rhode Island and Delaware can open the door to well-paying jobs and in-demand careers. And the Wall Street Journal recently reported that more students are taking advantage of apprenticeships, which offer workers on-the-job learning experience with pay, job-related classroom training, and the chance to earn a credential—all at little or no cost.

The catch is that in many places—including Ohio—there are access barriers and unanswered questions about program quality. The Buckeye State has prioritized strengthening education-to-workforce opportunities in recent years, but there are still thousands of students who lack access to or knowledge of available career pathways. (A mere 8 percent of students in the class of 2021 earned enough points in Ohio’s industry credentialing system to graduate based on their career experience and technical skill.) And while state leaders have improved overall data transparency, Ohio still doesn’t link K–12, post-secondary, and workforce outcomes. Without these data, it’s impossible to determine which of Ohio’s CTE programs and career pathways are valuable alternatives to a four-year degree.

Between the steep cost of higher education on one hand and CTE access and quality issues on the other, many young people end up adrift after graduating from high school. Strategic adjustments to state policy could give them the information and support they need to get back on track. In fact, the governor’s recently released budget recommendations contain several proposals that, if strengthened and passed, could lay the groundwork for some much-needed improvements. Let’s take a look.

Increasing support for graduates

DeWine has proposed establishing an office called ApplyOhio within the Ohio Department of Higher Education. It would be responsible for coordinating efforts to support Ohioans in “accessing a pathway to a post-secondary education after graduating high school.” Although state institutions of higher education are mentioned, the language also explicitly mentions Aspire programs (which provide free services to help adults acquire a variety of skills), Ohio Technical Centers (independently operated CTE centers that offer training and credentials for in-demand jobs), and other post-secondary institutions. In other words, ApplyOhio will be responsible for helping people access all types of post-secondary education, not just a traditional four-year degree. ApplyOhio would also help with efforts aimed at increasing the state’s Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) completion rate, improving the post-secondary admissions process, and recruiting Ohioans with some college credit but no degree to re-enroll in higher education.

At first glance, this might seem like just another layer of bureaucracy. But it’s actually a strategic move with two potentially huge benefits. First and foremost, it makes the state directly responsible for serving a population—recent high school graduates who aren’t enrolled in college—that typically gets overlooked. If the ApplyOhio office works as intended, it could step in and fill a massive void. In fact, the office could even partner with K–12 schools to ensure that students are more aware of their options before they graduate, thereby smoothing the often-bumpy transition. Second, re-engaging adults who already have some post-secondary education under their belts is crucial. For the individuals who are re-engaged, earning a credential or degree could vastly improve their job prospects and quality of life. And for employers, the talent pipeline will improve and expand. That’s a win-win that could significantly boost the state’s economy in the short- and long-term.

Investing in and improving CTE programs and infrastructure

One of the biggest headlines of DeWine’s budget is his increased investment in CTE programs and industry-recognized credentials. He’s proposed investing $26 million on industry-recognized credentials for high schoolers in both FY 2024 and 2025 and a whopping $50 million in new funding for CTE equipment during both fiscal years. DeWine’s budget would also require the Ohio Department of Education to increase the number of in-demand CTE programs across the state, and incentivize schools and businesses to offer work-based learning opportunities to thousands of students.

These are solid steps in the right direction, but the state can and should do more. A recently published brief from ExcelinEd and Ohio Excels offers four recommendations. The first, establishing a biennial return on investment analysis, would allow policymakers to identify which pathways are aligned with employer demand; evaluate student participation and outcomes for each program; and determine whether current offerings deliver on federal, state, and local investment.

Increasing awareness of college affordability

According to the Dayton Daily News, the cost of first-year tuition and fees at Ohio’s public universities rose about 4 percent between the fall of 2021 and 2022. That’s less than inflation, which went up by more than 8 percent, but an increase nonetheless. At most of Ohio’s public universities, a full year of tuition can cost between $10,000 and $13,000. On-campus housing can add, on average, about $12,401. Additional and unavoidable expenses, like textbooks, hike the price up even further. For example, U.S. News & World Report estimates that the total cost at Ohio State University for the 2021–22 academic year—an amount that includes tuition and fees, room and board, books, supplies, transportation, and personal expenses—was approximately $29,368 for in-state students. Financial aid and scholarship funds, though, brought the average cost down to roughly $18,165 for in-state students who receive need-based aid.

Eighteen thousand a year for four years isn’t cheap, but it’s definitely more manageable than $29,368. That’s why FAFSA is so crucial. By filling out this free form, students and families can apply for the grants, scholarships, and loans from federal, state, and local sources that make college more affordable. Many colleges and universities also use FAFSA to determine eligibility for their own institution-specific grants. To get a true picture of what higher education costs, families need to know how much aid is available—which means they need to fill out FAFSA.

Unfortunately, as of March 3, only 44 percent of Ohio’s class of 2023 had completed the form. It’s likely that a good chunk of students opted not to complete the form because they don’t plan to attend college and thus don’t believe they need financial aid. But given that affordability is one of the primary reasons why students are choosing not to attend college, it should worry policymakers that so many students are unaware of the financial assistance that would be available to them if they chose to enroll. This information could change the post-graduation plans for hundreds, even thousands, of teenagers. That includes high-achieving students from traditionally underserved backgrounds who would excel in college but don’t apply or enroll because they assume it’s out of their financial reach, as well as first-generation or low-income students who would benefit from the long-term financial boost of a college degree.

To increase FAFSA completion numbers, DeWine has proposed requiring every student to provide evidence of having completed and submitted the form in order to graduate. (He tried to pass a similar measure in the previous budget, but failed to get legislators on board.) There would be some exceptions, including allowing a parent or guardian to exempt their student by notifying the school that they won’t be completing and submitting the form. But for most students, FAFSA would no longer be optional. This seemingly small change would have an outsized impact, as it would raise awareness about the financial aid that’s available to students, and could push high schools to offer more assistance to families who are confused about how, when, or why to use FAFSA.

***

In Ohio, far too many recent high school graduates are struggling to find their place. The cost of higher education seems to be keeping students away from college campuses. Meanwhile, state leaders can’t guarantee that career pathways and CTE programs with the potential to be a viable alternative to a four-year degree are as accessible and high-quality as they should be. In his budget, Governor DeWine has proposed a variety of initiatives that could help address these problems. For the sake of younger Ohioans and the long-term health of Ohio’s economy, lawmakers would be wise to heed these proposals and build on them.

In a series of articles, I’ve been looking at various issues in school funding as Ohio lawmakers discuss the state budget. This piece looks at a special component of the funding formula, known as Disadvantaged Pupil Impact Aid (DPIA), which current provides districts and charters with $542 million in extra funding based on economically disadvantaged student enrollments.

One of the basic principles of equitable school finance is to fund low-income pupils at higher levels. This type of weighted student funding ensures that more dollars are available to help children who typically need more supports, whether that’s tutoring, summer school, or non-academic services. The extra dollars also support schools that may need to offer higher salaries to attract and retain talented educators who are willing to work in tougher environments. For many years, Ohio has followed this concept and funded economically disadvantaged students (as well as special education and English learners) at higher amounts via the formula.

The rationale for DPIA is sound, but the implementation needs improvement. In a problem that predates Ohio’s new funding model, the state significantly over-identifies economically disadvantaged students, which undermines the intent of the funding stream and soaks up dollars that could otherwise be used to better support students who are actually in need.

Like many other states, Ohio relies on free and reduced-price lunch (FRPL) eligibility to identify economically disadvantaged students. Historically, this has served as a decent proxy for income, as students need to come from households at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level to receive subsidized meals. But a 2010 change in federal policy has weakened the connection. Known as the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), certain higher-poverty districts and schools are now allowed to offer subsidized meals to all students, regardless of their household income. This makes sense as a way to address nutritional needs and is a paperwork saver for schools and families. But it has also led schools to report—inaccurately—that all their students are economically disadvantaged.

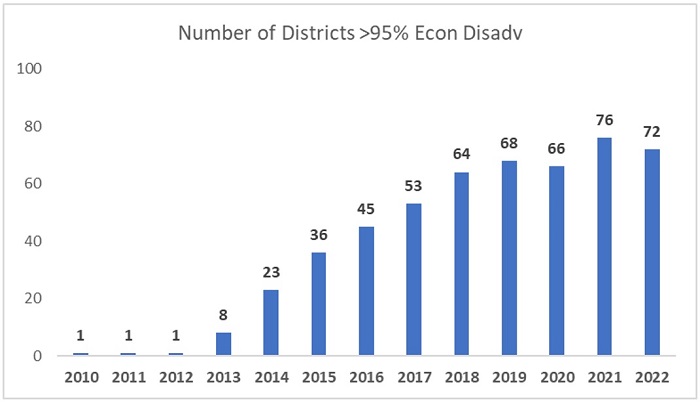

This wouldn’t be a big issue if CEP applied to a handful of schools here and there. But this year, seventy-two Ohio districts—more than one in ten—reported that 95–100 percent of students were economically disadvantaged (and almost 1,000 individual public schools did so). Figure 1 shows the marked increase in CEP eligible districts over the past decade. Prior to the meals initiative, just one district (Cleveland) reported universal economic disadvantage. But that number has grown significantly since 2012–13.

Figure 1: Number of Ohio districts reporting blanket economically disadvantaged rates

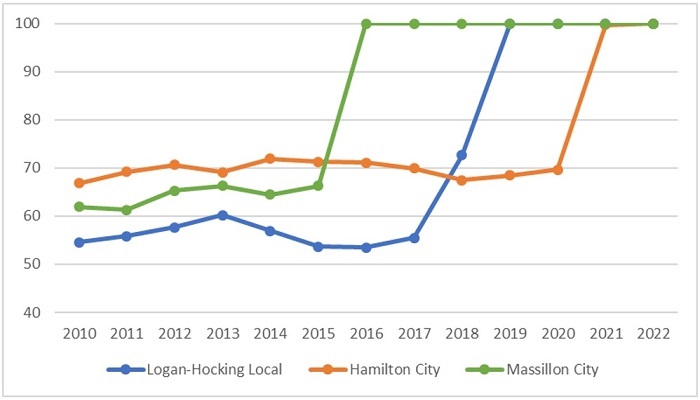

Figure 2 offers a closer look at how CEP inflates the data of three mid-poverty districts. Historically, Logan-Hocking, Hamilton, and Massillon school districts reported between 50 and 70 percent economically disadvantaged rates. But with CEP, those rates spiked to 100 percent in all three districts. Assuming that the 2010 data more accurately reflect the number of disadvantaged students in Ohio’s seventy-two CEP districts, the state over-identifies roughly 60,000 students as “economically disadvantaged.” This is a conservative estimate of the overcount, as individual schools also participate in CEP, even if their overall district does not participate.

Figure 2: Spike in economically disadvantaged rates in three Ohio districts after CEP

Inflated headcounts lead to an inefficient allocation of DPIA funding. To illustrate, let’s return to Hamilton City Schools, a district outside of Cincinnati. Table 1 shows its DPIA funding calculations (under a fully phased-in formula) using its currently inflated economically disadvantaged rate. It also shows a “simulated” DPIA calculation using its pre-CEP rate of 70 percent—almost surely a more accurate number. Note three things: (1) Hamilton’s “economically disadvantaged index”—a key multiplier that drives DPIA funding—doubles when it is allowed to report blanket rates. This, in turn, more than doubles its per-pupil DPIA amount, from $869 to $1,768; (2) Hamilton’s number of economically disadvantaged students swells by more than 2,500 students under CEP; and (3) its total DPIA funding almost triples when it’s allowed to report blanket rates. The district thus enjoys a nearly $10 million windfall because of CEP—an increase that pulls dollars away from districts that need them more.

Table 1: Illustration of inflated DPIA funding for a CEP district

Ohio legislators need to tackle these problems. Two steps would help.

Properly funding low-income pupils’ educations should be a priority for state lawmakers. Such students rely on effective schools and supplemental supports to reach their full potential. But without a reliable methodology for identifying them, Ohio is failing to target DPIA funds to students who need them most. The data quality problem is known. And with widening achievement gaps, the need to effectively target DPIA funds is great. It’s time for Ohio to transition to a more accurate count of low-income students, along with a better method for allocating resources for their education.

[1] It’s possible, for instance, that the squaring mechanism used in the economically disadvantaged index could produce extreme results, if there are districts that maintain high direct certification rates relative to a lowered statewide average (e.g., resulting in indexes of six to eight, which is then multiplied by $422).

[2] Right now, the true DPIA per-pupil funding amount is somewhat obscured through use of the economically disadvantaged index and the squaring mechanism. It creates a misperception that Ohio is adding just $422 per economically disadvantaged student in a high-poverty district, when in fact, it’s funding them at more than $1,000 extra per disadvantaged pupil.

Clearinghouses in education are entities that review research studies, analyze the effects of the interventions studied, and provide ratings of those interventions. Such ratings are relied upon more and more by states, educators, and schools as sources of fully-vetted, high-quality curricula and educational programs—and it is assumed that they’re based on deep analysis that verifies whether the models work as intended to help students learn and achieve. But how exactly do education clearinghouses work? Upon what evidence are programs and curricula rated? And how often do various analyses of the same curriculum agree? A new review aims to answer these questions and more.

A trio of researchers from George Washington University and Northwestern University initially collected a roster of forty-three education clearinghouses in the United States and the United Kingdom. The criteria for final inclusion were entities that conducted effectiveness analyses of education programs from pre-K to college, did not borrow their rating schemes from other clearinghouses, and produced ratings that were publicly accessible via the internet. A total of twelve clearinghouses met the criteria, all based in the U.S. The researchers collected and coded data from the clearinghouses between June 2019 and August 2020, including the types of interventions evaluated, their rating processes, funding sources, and the standards of evidence used to assess both research designs and the outcomes achieved.

A bit more about the dozen clearinghouses: Four were education-focused exclusively, while the other eight included additional areas. Most focused on student-centered programs only, some on programs serving children and their families, and one on programs specifically for military families. Some better-known clearinghouses include the National Dropout Prevention Center, the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), What Works Clearinghouse (WWC), and Best Evidence Encyclopedia (BEE). It may be simply a matter of timing that the extremely well-known EdReports was not included in the researchers’ short or long lists—their initial search of clearinghouses stopped in 2016 just as EdReports was ramping up its work—but its prominence in the space since then should warrant its inclusion in any future research. Funding for the clearinghouses reviewed comes from combinations of government, university, and foundation sources and varies greatly across the entities. The U.S. Department of Education, for example, reported to the authors that it had spent a whopping $100 million-plus supporting WWC; many other clearinghouses indicated that they operated on a fraction of that amount.

Available resources plus choice or area of concentration serve to shape the work of the various clearinghouses—including what and how many education programs they analyze. To list just three diverse examples: WWC employs experts to proactively search for programs to review according to an extensive protocol, the Corporation for National and Community Service Evidence Exchange only reviews programs that it funds, and the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness entity looks only at programs designed to boost school readiness. Program size, study design, and publication date also serve as criteria for inclusion in any given clearinghouse’s body of work.

Because the criteria used to evaluate programs differ greatly from clearinghouse to clearinghouse, the researchers worked hard to hammer out some useful comparisons. On the upside, all twelve clearinghouses cite randomized control trials (RCT) as their preferred research design and give greater weight to RCT studies and their outcomes than to other quasi-experimental designs. On the downside, the same type of non-RCT design that one clearinghouse readily accepts can be downgraded or even summarily rejected for analysis by others. Of the 1,359 educational curricula and interventions analyzed by these clearinghouses during the time of this study, 83 percent were assessed by just a single entity. Among those analyzed by more than one clearinghouse, similar ratings were achieved for only about 30 percent of the programs. Thus there’s not much “inter-rater reliability.” With many of those concurring ratings being low ones, perhaps the most comforting takeaway is that the duds seem easy enough for clearinghouses to spot.

The last third of the report is a set of case studies looking at all the possible combinations of outcomes for programs rated by multiple clearinghouses. Those deal with programs that earned maximal agreement in ratings across clearinghouses (both high ratings and low), modest agreement, modest disagreement, and maximal disagreement. The details of each are interesting—including the insistence of some clearinghouses on replication of findings, a state of affairs long lacking in education research—but the case of maximal disagreement is worth highlighting. Five clearinghouses reviewed research on the effectiveness of the very-well-known dropout prevention program Communities in Schools (CIS); it received one high rating, two middling ratings, and two low ratings. Among other factors, a lack of RCT studies available and some inconclusive impact findings among non-RCT studies dragged the program down for four of the clearinghouses. The one clearinghouse which gave CIS an unqualified thumbs up seemed to have its own source of RCT studies (not identified or linked) which presented enough positive outcomes to rate the program as “promising.” In short, the “evidence base” for different evaluations of the same program is wildly inconsistent for reasons unconnected to CIS itself. Spare a thought for any charter school or state education agency looking to make quality program or curricular choices in the face of these variables.

There are numerous limitations to this research, including a reliance on clearinghouses to have fully stated all of their criteria for study selection and rating on their websites. As a result, the researchers’ call for more clarity overall is sound. On the simpler side, that could mean clearinghouses add detail to their ratings—explaining, for example, that no program can earn a “recommended” rating without an RCT less than five years old, no matter what other evidence is available. Or it could mean more financial support for replication. On the more complex side, perhaps a central authority is needed to either police the varying evidence and ratings or to simply reduce the number of clearinghouses out there, which could also have the benefit of spreading resources to fewer entities, thus allowing more programs to be rated. As it stands now, clarity is clearly lacking in the clearinghouse space.

SOURCE: Mansi Wadhwa, Jingwen Zheng, and Thomas D. Cook, “How Consistent Are Meanings of ‘Evidence-Based’? A Comparative Review of 12 Clearinghouses that Rate the Effectiveness of Educational Programs,” American Educational Research Association AERA Journal (February 2023).

One way education systems have tried to raise the performance of Black and Brown children is by matching students with teachers of the same race and ethnicity. The conventional wisdom is that such practices are strongly supported by research, but a recent study published in Early Childhood Research Quarterly offers a contrarian view.

Two Penn State researchers used data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten (ECLS-K) to look at the national cohort of students who entered kindergarten during the 2010–11 school year, and to follow them through fifth grade. They included details from three tests of academic achievement, five teacher ratings of classroom behavior, and two independently assessed executive functioning tasks. The sample of 18,170 children is large and racially, ethnically, and economically diverse. The outcomes of interest were reading, science, and mathematics achievement; problem behaviors; self-control; interpersonal skills; approaches to learning; cognitive flexibility; and working memory. They also examined whether students were placed in gifted or special education classes.

Approximately 63 percent of students had a teacher of the same race or ethnicity during any elementary grade. Among White students, it was 92 percent, versus 45 percent for their Black and Hispanic peers. White students were especially likely to experience matching throughout most or all of elementary school—55 percent of them for five or six grades—due to the prevalence of White teachers leading elementary classrooms. The contrasting figure for Black students was only 3 percent, and 10 percent for Hispanic students.

For select groups, there were some positive impacts. For Black students, matching resulted in significantly fewer internalizing problem behaviors, such as anxiety, loneliness, and low self-esteem. And for Black girls, it also led to fewer externalizing problem behaviors, such as arguing and fighting with others, acting impulsively, and expressing anger. For students of any race or ethnicity who had previously displayed low levels of academic, behavioral, or executive functioning, racial and ethnic matching resulted in fewer externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors but, unfortunately, lower academic achievement. There was also a small but statistically significant negative effect on science achievement.

When looking at the entire sample, however, the impacts disappear: Student-teacher racial or ethnic matching was not associated with significant effects in reading or mathematics achievement, externalizing or internalizing problem behaviors, self-control, interpersonal skills, approaches to learning, cognitive flexibility, working memory, or gifted education service receipt. Students were less likely to receive special education services when they were taught by a teacher of the same race or ethnicity, but the level of significance is difficult to determine due to the small sample size of recipients.

The researchers properly note that their study focused only on elementary grades and might miss benefits of matching that emerge in middle and high school (or perhaps later in life), and they suggest further analysis along these lines.

SOURCE: Paul L. Morgan and Eric Hengyu Hu, “Fixed effect estimates of student-teacher racial or ethnic matching in U.S. elementary schools,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly (December 2022).

In 2013, Mississippi passed a comprehensive early literacy policy aimed at ensuring that students can read proficiently by the end of third grade, which research shows is a make-or-break benchmark. Among the reforms is a retention policy that—much like Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee, which was passed around the same time—requires students who don’t reach a minimum score threshold on state standardized tests to be retained in the third grade and receive additional support and intervention.

A recently published working paper from the Wheelock Educational Policy Center at Boston University offers a closer look at the effects of Mississippi’s test-based promotion policy. Using a regression discontinuity design, Kirsten Slungaard Mumma and Marcus Winters were able to compare the test scores, absences, and special education status of roughly 4,700 students who scored slightly above and below the state’s promotional score threshold. They found that students who were held back via the retention policy scored more than 1 standard deviation higher relative to their barely promoted peers by the end of sixth grade. That’s an enormous effect. It means that students who were retained in third grade scored, on average, around the 62nd percentile in English language arts when they were in sixth grade, compared to students who weren’t held back and scored on average in the 20th percentile. The impact was driven by gains for Black and Hispanic students, as both benefited substantially in ELA if they were retained. Retention had no significant impact on math scores, a student’s subsequent attendance rate, or the likelihood that they would later be classified as having a disability.

This isn’t the only evidence that Mississippi’s early literacy reforms are working. The Magnolia State has registered remarkable academic progress over the last decade, most notably on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). The state has shown significant gains in fourth grade reading since 2011, and from 2011 to 2022, ranked first among states in fourth grade reading gains. State test scores have also steadily improved, and across-the-board progress has been so impressive that it’s been hailed as a “learning miracle.”

What might Ohio observers take away from this data? First and foremost, it should give opponents of Ohio’s retention policy pause. Mississippi’s NAEP results, along with this new report and plenty of other research, make it crystal clear that a strong retention policy should be an important part of any statewide early literacy strategy.

Mississippi is also proof that statewide reading initiatives can be highly effective when they include resources and interventions beyond just retention. Mississippi leaders focused on the “right way” to teach reading, which meant championing the science of reading and ensuring that teachers knew what to teach and how to teach it. Literacy coaches were provided to identified schools and offered varying levels of support. Students who demonstrate a “substantial deficiency in reading” are required by law to receive intensive reading instruction and intervention, which must be documented in a reading plan. In other words, state leaders didn’t just toss out platitudes about the importance of improving early literacy. They passed laws, invested funding, and implemented programs designed to spark improvement—even in the face of significant pushback.

Ohio has already started down this path. The Third Grade Reading Guarantee requires struggling readers to be identified as early as kindergarten and put on reading improvement plans. The parents of struggling readers must be notified when their children are deemed off-track. And, of course, students who don’t meet the state’s promotional standard are retained in the third grade and must receive intensive intervention. Prior to the pandemic, these collective efforts were moving the achievement needle. But these improvements, at least on national assessments, haven’t been as swift or as stark as those in Mississippi. In the wake of Covid learning loss, it’s clear that Ohio’s youngest students need more.

Fortunately, Governor DeWine proposed some big changes aimed at bolstering early literacy in his recently released budget recommendations. They include establishing a state-created list of high-quality curriculum and instructional materials aligned with the science of reading, and requiring all public schools to use only the materials that appear on the list starting with the 2024–25 school year. He’s also pledged to provide funding to every school to pay for curriculum based on the science of reading and to fund coaches that can provide intensive support in low-performing schools.

In education policy, the best path forward isn’t always clear. But when it comes to early literacy, there’s plenty of light shining the way. We have a trove of research and evidence indicating what works, and thanks to states like Mississippi, we have a model for how to make it work. Now all Ohio needs to do is follow the light.

Over the past year, one of the most heavily debated topics in Ohio education has been the retention provision of the Third Grade Reading Guarantee, a decade-old package of early literacy reforms. Under the retention policy, schools must hold back students (with limited exceptions) who are struggling to read at the end of third grade and provide them intensive literacy supports. This requirement aims to ensure that all children have foundational reading skills before they are asked to tackle more challenging material in the middle and upper grades.

Despite the sound rationale, critics have long decried the policy as being hurtful to retained students. Their claims are often based in anecdote and crude interpretation of data. In November, the State Board of Education—a body that has been hostile to retention—presented data showing that less than one in six retained students achieve the state’s reading proficiency target in subsequent years. Based on these numbers, board members argued that the policy “has not achieved the desired result” and passed a resolution asking the legislature to scrap the requirement (which lawmakers have, so far, not done).

Yet such a brazen condemnation of Ohio’s Reading Guarantee is hardly warranted based on these data. Instead, as the debate continues, policymakers should heed more credible evidence about the effectiveness of retention, including a brand-new study that examines Indiana’s third-grade retention policy, to which we return a few paragraphs hence.

Let’s first review some problems with using raw proficiency numbers to make judgments about retention.

For starters, retained students could be making good progress in later grades, but focusing only on their “proficiency”—a relatively high bar that roughly 40 percent of Ohio students fall short of—would overlook those gains. Obviously, ensuring that every student is a proficient reader is an important goal for schools. But progress toward proficiency matters, too. Perhaps a retained student is moving from the 2nd to 15th percentile by fifth grade. That type of growth should also be part of any evaluation of the retention policy. Moreover, the raw numbers lack any context that could help us understand the actual impact of retention. How do retained students perform relative to other low-achieving students who narrowly pass the reading requirement? Do they make more or less progress than their close counterparts? Answers to such questions would provide a clearer picture of whether retention is better for low-achieving students than the alternative of “socially promoting” them.

Unfortunately, a careful evaluation of Ohio’s third-grade retention policy has not yet been undertaken. That should certainly change. But there has been strong empirical work from Florida that uncovers positive effects of retention under its early literacy law (those findings are discussed in an earlier piece). A recent report published by the Annenberg Institute at Brown University also reveals positive impacts of third grade retention in Indiana.

The analysis was conducted by Cory Koedel of the University of Missouri and NaYoung Hwang of the University of New Hampshire. Akin to Ohio’s and Florida’s reading policy, Indiana requires third graders to achieve a certain target on state reading exams in order to be promoted to fourth grade. The policy went into effect in 2011–12 and the analysts examine data through 2016–17. Using a “regression discontinuity” approach, Koedel and Hwang compare the fourth through seventh grade outcomes of retained students to their peers who just barely passed Indiana’s promotional threshold. This methodology (also used in the aforementioned Florida study) provides strong causal evidence—almost as good as a “gold standard” experiment—about the effect of holding back low-achieving third graders.

Here are Indiana’s impressive results:

The authors conclude, “Taken on the whole, our findings of positive achievement effects of the Indiana policy, coupled with the lack of negative effects on attendance and disciplinary outcomes, suggest grade retention is a promising intervention for students who are struggling academically early in their schooling careers.”

When lawmakers passed the Buckeye State’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee more than a decade ago, they did so because they recognized the importance of early literacy to students’ long-term success. Dropping the retention provision of the guarantee based on anecdotes and flimsy data would be reckless, potentially leaving thousands of Ohio students at risk of not receiving the extra time and support they need to read fluently. Holding back third graders struggling to read has worked in other states. It can work—and may very well be working—in Ohio, as well.