The romance versus the reality of teacher pensions

Pensions, a promise of guaranteed lifetime income for retirees, have been around since antiquity.

Pensions, a promise of guaranteed lifetime income for retirees, have been around since antiquity.

Pensions, a promise of guaranteed lifetime income for retirees, have been around since antiquity. No other than Caesar Augustus is said to have created a pension fund for army veterans. Expanding far beyond the military, today’s pension systems cover some private sector employees and large swaths of government workers, including public school teachers. In 1911, Massachusetts opened the nation’s first teacher pension; Ohio founded the State Teachers Retirement System (STRS) in 1920 to administer pensions.

Traditional pensions have grown to almost mythical status in the public sector, billed by proponents as a gratuity for a career of service and a recruitment tool. But behind the legend stands a messier reality. In a prior analysis, I looked at the massive costs of pensions to Ohio teachers and schools. This piece looks at three additional problems that plague the system.

1. Snubbing teachers who leave “too early”

Early and mid-career teachers lose significant retirement wealth if they choose to separate from the system, whether to take teaching positions outside of Ohio, pursue other career opportunities, or take care of children at home. Consider what happens to short- and medium-tenure teachers.

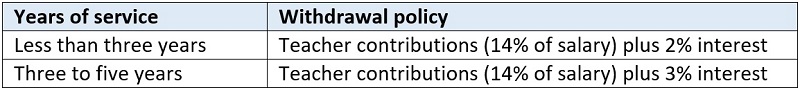

Short-tenure teachers: Individuals who teach less than five years are not entitled to a pension—they’re not “vested”—but are allowed to withdraw funds they’ve contributed when they exit. The table below shows the rules.

Table 1: Withdrawal rules for non-vested teachers

Source: STRS, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, 2021 (p. 74)

At face value, this doesn’t look so bad. But remember that STRS requires contributions from both teachers and their employers to fund retirement benefits—a rate of 14 percent of salary, each. What’s missing is the employer contribution. Short-term teachers don’t get any of that money—it instead goes to help pay other people’s retirements. Some may argue that a teacher shouldn’t be entitled to that portion, but it doesn’t the change the fact that retirement dollars generated by the teacher’s salary—and her work—are being diverted elsewhere.

The money lost is significant. For a teacher with four years of service and earns $150,000 in total salary, the employer share adds up to $21,000. If she put those dollars in a IRA yielding 5 percent annually, she would have more than $90,000 in thirty years.

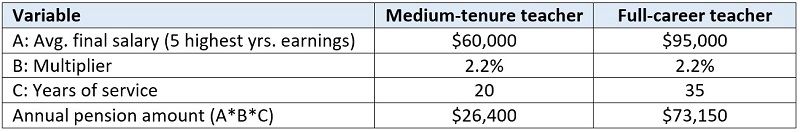

Medium-tenure teachers: Those who teach longer—but not to retirement age—may opt to receive pension benefits (lifetime payments) or withdraw their funds. Unfortunately, the system also shortchanges these teachers, some of whom work a decade or two in the classroom.

A trifecta of policies hurt mid-career teachers who opt for the pension option. First, the value of a pension hinges on a worker’s final average salary before exiting the system. But because mid-career teachers are lower on the seniority-driven salary schedule, their retirement benefits will be rather modest to begin with. Second, their final average salary isn’t indexed for inflation, a greater issue for early leavers who must wait to collect benefits for twenty or thirty years into the future. Think of it this way: A medium-tenure teacher who is retired today could be receiving benefits based on earnings from twenty or thirty years ago—a salary that has long been eroded by inflation. This is less of an issue for full-career retirees, whose final salaries are from more recent years. Third, medium-tenure teachers aren’t eligible for payments until age 65, an older age than when most teachers meeting the full retirement criteria start collecting benefits (mid 50s to early 60s). Delaying benefits reduces the value of the pension, as teachers receive fewer years of payouts.

As a result of these policies, teachers separating “too early” receive benefits that are not commensurate to their contributions to the pension system and work in the classroom. Table 2 illustrates the meager benefits that a teacher with twenty years of experience would expect to receive if she left STRS. Remember that Ohio teachers are not in Social Security, so they rely more heavily on their pension.

Table 2: Illustration of pension amounts for medium-tenure versus full-career teacher

Calculations are based on the pension formula stated in STRS, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, 2021 (p. 73).

Medium-tenure teachers electing for a lump-sum withdrawal also pay a price. While they get 1.5 times their own contributions refunded (plus 3 percent interest), they don’t receive the employer contribution. For early leavers whose employee-employer contribution rate was 14 percent each, they effectively sacrifice half of their employer contribution (7 percent). Thus, a teacher with two decades of experience and total earnings of $900,000 would forfeit $63,000 in employer contributions.

Economist Robert Costrell writes, “Most teachers earn little or no employer-funded benefit if they leave before about age 50. The employer contributions made on their behalf help fund the benefits of those who stay longer. This is intra-generational redistribution.” Calling this system “redistribution” is almost too polite. What it does is rob Peter to pay Paul. In so doing, it cheapens the work of young teachers on behalf of students.

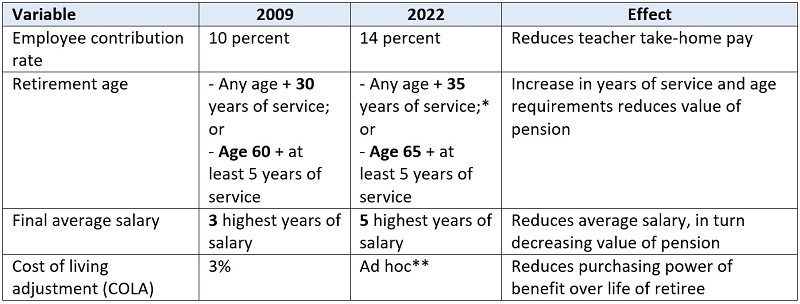

2. Exposing career teachers to financial pain

Career-teachers who reach retirement age do reap better benefits than their unfortunate counterparts. But even for them, the system is not entirely free of risk. Though pensions guarantee lifetime income, it doesn’t shield them from policy changes that reduce their wealth. Consider the table below, which shows changes in STRS’s pension rules. First, note that the employee contribution rate has risen significantly in the past decade, cutting teachers’ take-home pay. Yet despite the higher costs, benefits haven’t risen. They’ve actually been cut. In 2009, for example, teachers needed thirty years of service to retire and receive benefits right away. Teachers will soon need thirty-five years of service, an elongated period that reduces the value of the pension. For instance, raising the service requirement by five years costs a retiree $250,000 in pension value if it’s worth $50,000 per year. Meanwhile, the suspension of cost-of-living-adjustments (COLAs) starting in 2017 has infuriated retirees, especially now that inflation is through the roof, and STRS only recently reinstated a one-time adjustment. In a recent interview, one teacher aptly summed up the situation: “I am working longer and getting less money for it.... It is criminal.”

Table 3: Changes in STRS policy between 2009 and 2022

Sources: STRS Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports and Chad Aldeman, Default Settings. * The increase to 35 years of service is being phased-in and will apply first to teachers retiring after 2023. ** STRS suspended COLAs starting in 2017, but it recently provided a 3 percent, one-time adjustment for 2022.

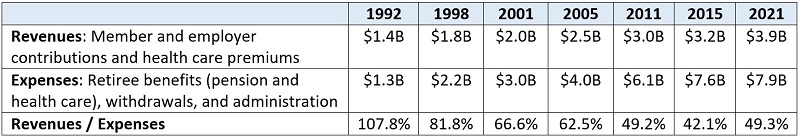

3. Taking massive investment risks to cover funding gaps

Over the years, STRS has needed to rely more heavily on investment income—not simply contributions from workers and employers—to fund retiree pensions. Table 4 shows that, in 1992, the system took in more than it paid out. But starting in the late 1990s, the picture rapidly shifted, with the growth in outlays far outpacing revenues. Today, annual contributions fall billions short of the amounts paid to retirees.

Table 4: STRS revenues (less investment income) versus expenses, selected years

Source: Ohio Retirement Study Council, STRS Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports.

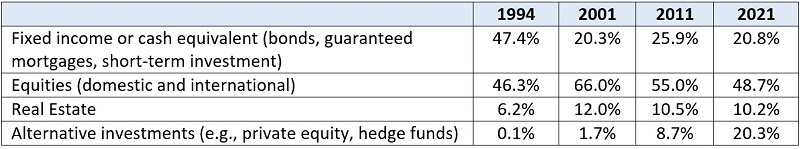

To cover the escalating costs, STRS has several options. It could require higher teacher or district contributions, it could ask legislators for more funds, or it could cover expenses by pursuing large investment returns. Indeed, STRS bets big on investments, as have other pension systems in Ohio and around the country. Table 5 shows that STRS’s portfolio has shifted away from safer investments to equites, real estate, and alternative investments. While those instruments can yield strong returns in years of plenty, they are also riskier than treasuries or cash equivalents. As occurred during the Great Recession, a risk-taking portfolio can lead to huge losses and massive increases in a pension’s unfunded liabilities (equites, real estate, and alternatives all slid during 2008 and 2009).

Table 5: STRS’s investment portfolio, selected years

To be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong with individuals putting their own money into stocks or private equity. They reap the benefits or bear the consequences. The problem with inordinate risk in this context is that pensions guarantee benefits to retirees. If stocks tank or a hedge fund collapses, STRS can’t—and shouldn’t—stop making payments or cut benefits to the bone. Someone, either teachers or taxpayers, will have to cover the costs.

The misalignment between immutable pension obligations and uncertain investment returns is one reason why some experts recommend that pensions reduce their assumed rate of return—STRS’s is currently 7 percent—and pursue more conservative strategies. The policy dilemma, however, is that reducing the discount rate would increase unfunded liabilities, which in the case of STRS is already at $21 billion.

***

Far from being the Rock of Gibraltar on which teachers can build their retirement dreams, Ohio’s pension system is more akin to a house of cards that imperils teacher and taxpayer money and pickpockets short- and medium-term educators in a cruel effort to make ends meet. Of course, STRS isn’t alone in the national pension nightmare. As Josh McGee writes:

[Public retirement plans] are bigger and riskier than ever before, and their growing annual cost is crowding out spending in important areas like public safety and education. Public workers bear a significant share of increased pension cost through stagnant wages, benefit reductions, and worsening job conditions. And many jurisdictions are not prepared for the next major economic downturn.

The question now is whether Ohio policymakers are willing to make the hard choices that can create a fairer, more fiscally sound retirement system, one that ensures all teachers—from young to old—receive the hard-earned benefits they deserve.

According to the state’s most recent annual report on educational attainment, 49.5 percent of Ohio adults had a postsecondary degree or other credential of value in 2019. That’s an increase of 14.8 percentage points since 2009, but it’s still a long way from the 65 percent goal state leaders set in 2016. To bridge the bulk of the gap, Ohio will need to focus on adult learners. But to maintain growth and strengthen talent pipelines, it’s also crucial to focus on future adults: current and rising high school students.

Ohio already has a decent foundation. Most high schoolers have access to a broad range of career and technical education (CTE) programs. State graduation requirements include a career-focused pathway. Dual credit opportunities are plentiful in both academic and technical fields. But even with these myriad options, thousands of Ohio students graduate each year with no industry-recognized credentials, no solid job prospects, and no idea how to make postsecondary education work for them. The pandemic has likely made things worse. It’s changed the economy and made in-demand credentials even more valuable for both employers and graduates, but information about and access to these credentials hasn’t necessarily improved.

State leaders can help by investing in innovative high school models that prepare students for college and career. These schools give students a solid academic foundation but also provide career opportunities through internships, mentoring, and work-based learning. Students follow rigorous pathways that lead not just to a high school diploma, but to industry-recognized credentials and associate degrees in well-paying, in-demand fields.

Ohio already has a few schools like this. There are dozens of career centers across the state that offer students CTE programming in addition to traditional high school courses. Early college high schools, like Dayton Early College Academy or Metro Early College High School, require students to complete college coursework and internships to graduate. But these schools and programs serve only a fraction of the state’s high school population. To keep attainment numbers growing for the long term and to aid young adults in navigating a post-Covid world, Ohio needs to invest in other models, as well.

P-TECH is a promising option. Unlike a typical high school, P-TECH schools span grades 9–14. Students graduate with both a high school diploma and a two-year postsecondary degree, and they participate in work-based learning experiences, such as mentorships and internships as they work their way through school. In his most recent executive budget, Governor DeWine proposed a pilot program that would permit schools to apply for funding to implement the P-TECH model. Unfortunately, the pilot didn’t make it into the final approved budget. But lawmakers can and should revisit their decision. Ohio’s immensely popular College Credit Plus program makes the postsecondary aspect of the model relatively easy to implement, and programs like TechCred have proven that there are plenty of businesses invested in credential attainment.

If state leaders are interested in giving advocates and communities the freedom to create their own innovative models, a recent paper entitled The Big Blur offers some insight. It proposes a new educational model that, like P-TECH, would erase the dividing line between high school and college by creating new, cost-free institutions that serve sixteen- to twenty-year-old students. Foundational coursework from the final two years of high school would be combined with career-specific training. Work-based learning would be a key feature, and students would have clear, step-by-step guided pathways that lead to high school diplomas, as well as postsecondary credentials and associate degrees within specific fields.

Creating and running these new institutions would be a huge undertaking. Lawmakers would have to set clear legislative guardrails around incentives, governance, and staffing. But they would also need to offer meaningful flexibility and plenty of funding and technical support. There are a lot of potential hurdles. But there’s plenty of time before the next budget to sort through them and create a promising pilot program.

If lawmakers are serious about addressing attainment gaps, making room for innovative high schools is critical. There are plenty of ways to do so. State leaders could increase Ohio’s investment in schools that already exist, such as career centers and early college high schools. They could bring in proven models like P-TECH. Or they could create and fund pilot programs that make it possible for advocates to build completely new institutions. Regardless of what they choose, one thing is certain: It’s time for Ohio to get innovative with high schools.

School reopening decisions following emergency pandemic closures have been sources of much parental angst, pundit caterwauling, and political controversy. Now that most of the dust has settled, new research gauges what was really happening in U.S. schools during this turbulent time.

The analysis comes to us from the IZA Institute of Labor Economics and was conducted by two economists from Drexel University and the Université du Québec. They begin with scheduling data from the school-calendar software provider Burbio and link them with the pandemic-era tracker Return2Learn to determine whether public and private schools reported being open for fully in-person or hybrid learning for every individual school day during the 2020–21 school year, which is to say the school year most thoroughly affected from beginning to end by the plague that is still with us. They cover nearly 70,000 traditional district, charter, and private school buildings across the country.

What schools say they are doing and whether students are actually in buildings could be two different things. The analysts thus match anonymized data from more than 40 million cell phones via Safegraph to individuals actually traveling to these school buildings during times they were meant to be open for teaching and learning. “Dwell time” at school sites is used to eliminate people visiting briefly for meals, homework pickup, and the like. The study uses the term “effective in person learning” (EIPL) to denote provision of on-site education that was actually attended by students—with “effective” meaning “being in effect” rather than “being successful at a task”—but it is important to note that this research does not determine the percentage of enrolled students in their building when opened. It is likely to be far less than 100 percent of pre-pandemic numbers.

Although EIPL had dropped below 20 percent of its pre-pandemic level in most places during spring 2020 when Covid first hit, it rose to move than 50 percent on average during the 2020–21 school year. However, large differences were evident. Some of these were regional. For instance, some cities in Florida (such as Jacksonville, Orlando or Tampa) showed EIPL averaging more than 75 percent from September 2020 to May 2021. Conversely, in some western cities (such as Los Angeles, Portland, and Seattle), EIPL remained at an average of 20 percent or less more than a year into the pandemic.

The analysts also find clear cut disparities by school type. Briefly: Public schools provided substantially less EIPL than private schools, with charters ranking below traditional district schools and private nonreligious schools ranking below private religious schools. For both public and private schools, EIPL was lower in more affluent and educated localities with a larger share of dual-headed households, but also for schools with a larger share of non-White students. For public schools, EIPL was negatively related to pre-pandemic school test scores, school size, and school spending per student. Additionally, and perhaps alarmingly, EIPL was negatively related to federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding per student, despite this effort being expressly aimed at helping schools reopen in person learning. The researchers don’t have a plausible explanation for this inverse relationship, although they note that previous research suggested that only a tiny fraction of ESSER funds had been spent on anything as of August 2021. It has also emerged that schools have used Covid-relief money for lots of initiatives that have very little to do with students actually being in their buildings.

In looking at non-school factors that might correlate with EIPL patterns, the analysts found that most of the inverse relation of EIPL with local affluence, education, parental structure, and school funding can be explained by—wait for it—whether the state’s governor was a Republican and the margin by which the local county voted Republican in the 2020 presidential election. Covid vaccination rates also predict higher EIPL (more vaccinations, more in-person learning), while a state’s teacher unionization rate predicts lower EIPL (more union teachers led to less in-person learning, everything else being equal). In contrast, local Covid case and death rates and whether a school is located in a city, suburb, or town/rural area do not have significant predictive power. Explanations for these observations are not offered. The report’s authors are also clear that no causal relationships can be determined with these data. But they do strongly suggest that school reopenings were “driven in large part by policies that align with local political preferences.” Or, more briefly: All the Twitter memes you read or posted were accurate.

SOURCE: André Kurmann and Etienne Lalé, “School Closures and Effective In-Person Learning during COVID-19: When, Where, and for Whom,” IZA Institute of Labor Economics discussion paper (January 2022).

How many teachers know even the basics about their retirement plan? Too few according to a recent study by Dillon Fuchsman of Saint Louis University and Josh McGee and Gema Zemarro of the University of Arkansas. Young teachers in particular have very little understanding of their retirement plan.

The researchers give a five-question “pop quiz” to a subsample of teachers who participate in the RAND Corporation’s American Teacher Panel survey. The questionnaire was fielded in February and March 2020, and 5,464 teachers completed it. The analysts cross-referenced teachers’ responses with the retirement plans of their respective states to check the answers. Respondents from a few states, including Ohio, were dropped because their state offers a choice of retirement plans; thus, linking a teacher to a singular plan wasn’t feasible.

The topics and results of the survey are as follows:

Predictably, given their closer proximity to retirement, experienced teachers were more likely to answer correctly than younger ones. For instance, 63 percent of late-career teachers accurately identified their retirement-plan type, versus 50 percent of early-career teachers. On the benefit-duration question, 81 percent of late-career teachers answered correctly, while fewer early-career teachers got it right (55 percent).

Teachers have lots on their plates and probably aren’t poring over the minutiae of their retirement plans. And haziness about retirement plans isn’t limited to the teaching profession, either, as workers in other career fields also struggle to comprehend the rules and terms of their plans. But what’s apparent from this study is that teachers, especially younger ones, could use better information about their retirement plans—and their options, if such are available. With clear information, teachers should be able to better plan their futures.

Source: Dillon Fuchsman, Josh B. McGee, and Gema Zamarro, Teachers’ Knowledge and Preparedness for Retirement: Results from a Nationally Representative Teacher Survey, Sinquefield Center for Applied Economic Research Working Paper (January 20, 2022).